1940s—Diplomat and World War II Heroine

The life of Constance Ray Harvey (1904-1997) sounds at times like something from the movie “Casablanca.” During World War II, after tours in Milan and Bern, she was stationed in Lyon, where she worked with the Belgian and French Resistance movements. She smuggled documents to the U.S. military attaché in Switzerland, General Barnwell R. Legge, who helped arrange the escape of many interned U.S. fliers. In November 1942, Harvey was interned along with other American diplomats when the Nazis took control of Vichy France. After the war she received the Medal of Freedom for her courageous efforts.

Constance Harvey was interviewed by Dr. Milton Colvin and Ann Miller Morin in 1988.

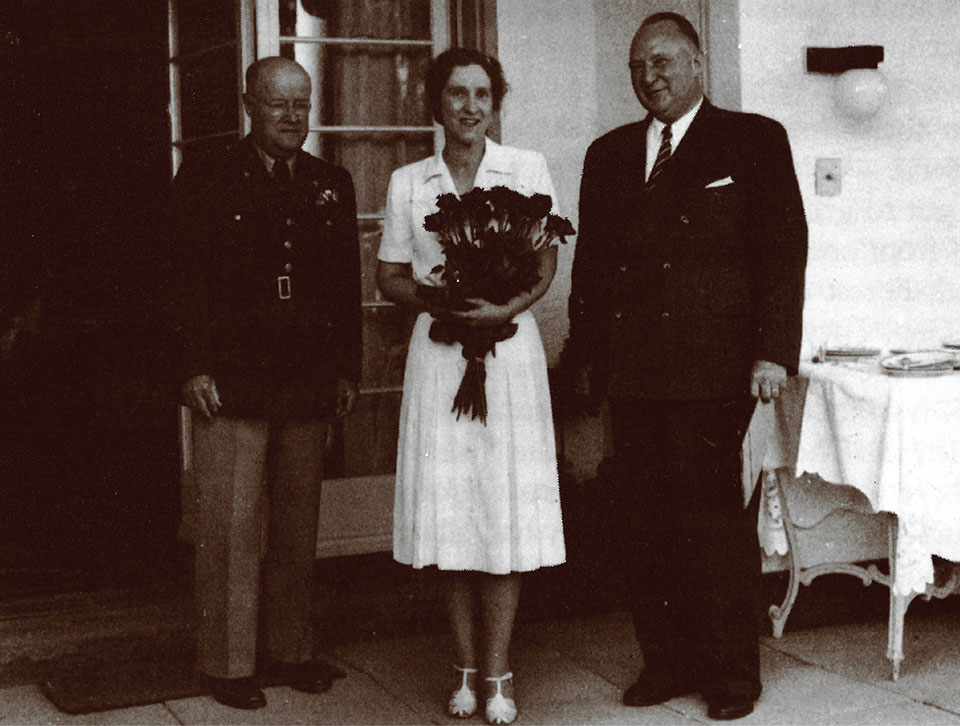

Constance Ray Harvey, after receiving the Medal of Freedom in 1947 for meritorious service with the French Underground during World War II. At left is General Barnwell R. Legge, the U.S. military attaché in Switzerland with whom she worked.

From Her Excellency by Ann Miller Morin (Twayne 1995).

I was vice consul in Lyon under the Vichy government. I went there on New Year’s Day of 1941. I still had an apartment in Bern, but I rented it to the British military attaché. I went back to Bern rather frequently. I had a car and I sometimes drove back and forth. …

[General Barnwell R. Legge] was in Switzerland all during the war. Years later, when I was back in Washington after the war was over, I learned, not from him, but from somebody quite different, that he sent the best information our government got during the whole of the war about what was going on on the eastern front. Legge had people all over Europe, a network of people, and I became one of his people.

We had a very good arrangement. The pouch went through Geneva and Vichy, and then back through Lyon to Bern, and then on the way across Spain to Portugal and on to Washington. When the pouch came back from Vichy to Switzerland, I was the last person in Lyon to buckle up this big bag. I put into it whatever I thought was suitable. Not even my chief knew all that went into that bag. But I knew it went straight to Legge and was one of the quickest and surest ways of communicating with our government in Washington.

I knew a lot about the Belgian situation. One of my clerks had been for many years the economic adviser to the American embassy in Brussels, and when Belgium was occupied, he was transferred to Lyon.

We had a lovely time getting out prominent people, practically all of the Belgian government in exile. When we got out the man who was the former Belgian military attaché in Vichy, with a nice passport under a false name to go across Spain, we thought we’d done quite a good job.

These were all, of course, Belgian passports which had been fixed up, usually arranged by Jacques Lagrange and his wife. Jacques was the Belgian clerk who created these works of art at home with the proper photographs and descriptions, which were quite imaginative. It looked right and official. And all of these people went out with nice Belgian passports issued by the kindly protecting power, and signed by C.R. Harvey.

After the war, one of these people came into our embassy in Brussels and said, “Here’s the passport that was given to me by Miss Harvey. I’ve always remembered her.”

The Belgians had a very good underground network. As a matter of fact, our office sometimes looked like a recruiting office, because when the Belgian radio, which broadcast from London to Belgium, began to urge young people who wanted to go out to join either the Belgian Army in the Congo or to come to London, they’d say, “Make for the American consulate in Lyon.” They would come in. Sometimes these people certainly looked rather “suspicious,” and were the ones that we could not get out with passports. They had to be taken out “black”—i.e., by special guides.

We had a lovely time getting out prominent people, practically all of the Belgian government in exile.

–Constance Ray Harvey

People were divided about the Vichy government. We couldn’t help but see both kinds in a way, but people made little waves. They didn’t dare talk too openly, you see, because they never knew when the Gestapo would arrive and scoop you up. We had Gestapo coming into the office constantly. We were very careful not to find out too closely who came into that office. We didn’t ask too many questions. We found it better not to know always. Some of them, we knew pretty well, were members of the Gestapo, which was quartered right across the street from my hotel, in the hotel where my consul general was lodged.

One had to be very careful with whom one spoke, because they might be on one side or the other and go and tell what you said. So before you got into politics of any kind, you had to know the person really well with whom you were speaking. The French are apt to chatter a bit too much. I was traveling on a train from Vichy back to Lyon once, and happened to sit next to one of the rather famous French generals, General de la Laurencie, and he started to talk to me, you see, because he was very anti-Petain. I was terrified with what he was talking about. …

I want to back up a bit and tell you a little bit more about the work I’d been doing regularly for our attaché in Bern, Gen. Legge. I went personally to Switzerland every once in a while, carrying documents to him and reports which we had from the occupied zone and from other places and, of course, from Belgium and so forth.

Once, for instance, I arrived and we met in a field outside of Geneva. I presented him with some documents that had been brought down to me by one of the agents that we had working in the north, who brought information to us. They were the maps of all the emplacements of the antiaircraft equipment of Germans all in and around Paris. He turned sort of white and said, “Oh, for goodness’ sake, you just brought this in by hand?”

I said, “Oh, yes, no problem.” I had a Ford car, and when you crossed the frontier, there was always a member of the Gestapo right at the frontier with a French officer, watching as you went back and forth. That Ford car had a glove compartment for which there was a separate key, not the key to the rest of the car, the ignition. So when I went in, I just locked up papers inside the glove compartment and turned the key down inside my bosom.

When I went into the place to check out with the French officer and the Gestapo to go into Switzerland, I left my car open, with the keys just hanging from the ignition. Sometimes people had hidden things in the machinery under the hood, and they sometimes looked under the hood. I thought that was something to avoid.

I remember the general said, “I shall remember that, Constance.” So later, when he gave me the Medal of Freedom, I guess he remembered.