From the FSJ Archive—Arms Control Diplomacy

The Man Who Made Arms Control ‘Respectable’: An Interview with William G. Foster

William G. Foster was named in 1961 by President Kennedy to be the first Director of what is still the world’s only governmental agency of its kind, the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. … In this interview by a member of his former staff in ACDA, Ambassador Foster takes a wide-ranging look at the past, the present, and the future of arms control.

… As it turned out, the business of arms control not only became respected, but respectable as well, thanks to the foresight and the courage of President John F. Kennedy. Mr. Kennedy was not only deeply interested in the subject but was an enthusiastic supporter of the idea. With this kind of backing we managed to put together a team of practical men who were surely anything but dreamers.

Pretty soon, what had seemed to most people to be a sort of pastime began to attract the very real interest of the Department of Defense, the Atomic Energy Commission, and of course that of our landlord, the State Department. Some of the brightest minds in the fields of foreign affairs, defense, and science joined us. But most important of all, we had a law—the Arms Control and Disarmament Act of 1961—to help us get things done. And we had some difficult work to do, not only externally but I might say internally as well. …

Now, people say the Soviets never live up to their agreements. But if you get agreements down in black and white, and if you have complete understanding of the nature of the problem and the method of dealing with it, mutuality of interest in preserving such agreements becomes almost automatic.

It has been my experience that where you do have that kind of understanding and have it directly committed, agreements do stand up. This has been true of the Antarctic Treaty, it is true of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, and it is true of the Outer Space Treaty. You must remember also, of course, that U.S. arms control policy requires that there be means for adequately verifying compliance with agreements.

—Nicholas Ruggieri, February 1971

The Prevention of Nuclear War in a World of Uncertainty

Let us admit that we are dealing in this field with arguments based on only plausibility, not experience. Many of these arguments can be constructed just as convincingly in their logical opposites. And since nuclear policy cannot possibly be based on actual experience—let us hope and pray it never can—it tends to feed on itself. It gets no feedback from the real world, no empirical evidence of the incontrovertible kind that buttresses the physical and even the social sciences.

In this sense we are a ship sailing through the night guided only by the light at the prow. Because nuclear strategy cannot offer positive proof, I think it is more like a theology than a science. Hence, we run the risk that our “theologies,” ours and the Russians’, may not be in harmony. Sudden incompatibilities can develop in military thinking and could lead to catastrophe. All the more reason, then, for us to keep our minds open and not plan the future by listening only to the echo of our old ideas.

—Fred Ikle, May 1974

The Essence of the Debate over SALT II

One of the most striking gaps in the analysis of those opposed to the [SALT II] treaty is any really systematic discussion of how the United States will in fact be better off if the treaty is rejected. Even if one accepts, for the sake of argument, that a tougher bargain might have been struck with the Russians—a generally dubious proposition in itself—simply rejecting SALT as “inadequate,” or attaching major substantive amendments to the treaty that Moscow is bound to reject, would be virtually irrelevant to the “redressing” of the Soviet-American nuclear balance. The issue more specifically is how, without SALT II, that nuclear balance will be more advantageous to us by the end of 1985 when SALT II is scheduled to expire.

—Stephen Garrett, October 1979

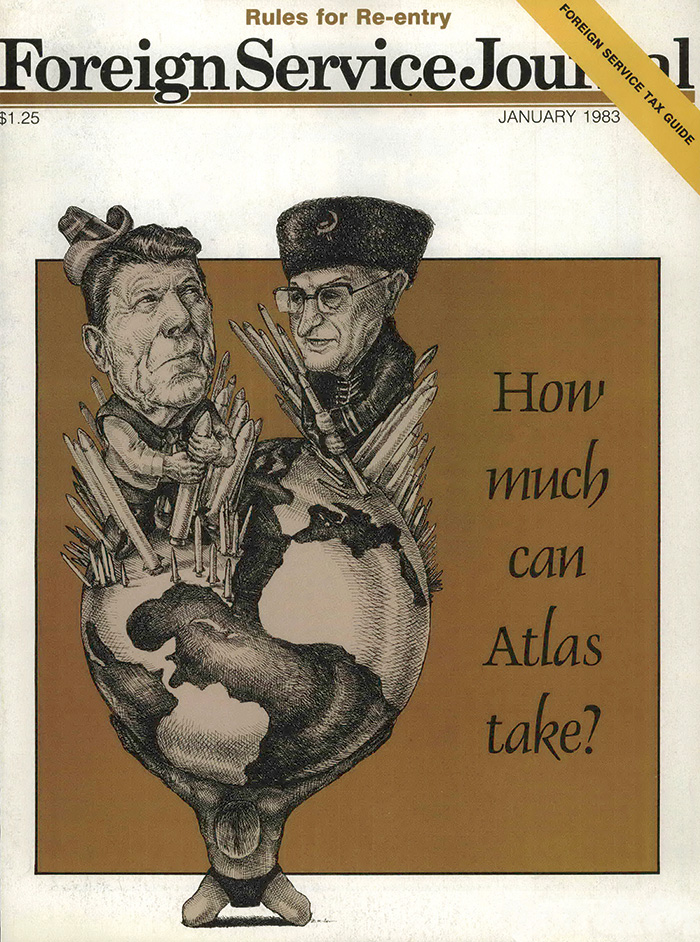

Restarting START

Contrary to [President Ronald] Reagan’s assertions, more nuclear weapons are not needed to serve as bargaining chips in START. More weapons would make it harder, not easier, to achieve mutual reductions. Soviet leader Yuri Andropov’s call for renewal of detente in his hard-line speech immediately following Leonid Brezhnev’s death made it clear that the Soviet Union would respond to a U.S. arms buildup with a build-up of its own. Thus, the funding and deployment of more American weapon systems, such as the MX, Trident II, or ground- and sea-launched cruise missiles, will result in more Soviet arms. And, in an ever-spiraling process, more Soviet arms will in turn result in more U.S. arms.

Today, the United States already has thousands of nuclear weapons it could trade away without jeopardizing its security. And both sides could gain some bargaining leverage from the new and more deadly weapons still under development—a Soviet mobile ICBM, for example, or a U.S. sea-launched cruise missile—providing that leverage is used in negotiations before the weapons are deployed. It is only then that the U.S. or Soviet negotiator could offer to delay or cancel deployment or outline what conditions would lead to deployment.

The issue of nuclear weapons is at the center of the U.S.-Soviet relationship, and an agreement resulting in substantial reductions would have far reaching political effects. The Reagan administration should therefore introduce a new proposal on START.

—David Linebaugh and Alexander Peters, January 1983

Accepting Nuclear Weapons

Is there any reason to believe that the Soviets would not capitalize on the enormous military advantage that goes with first nuclear use?…

NATO’S central military problem is that it has opted out of the Nuclear Age, while the Soviets have unhesitatingly accepted it. Neither Americans nor Europeans have been willing to contemplate nuclear weapons seriously as warfighting instruments. The Soviets always have. This fundamental doctrinal disparity has placed the alliance in an untenable position regarding realistically defending itself. The West’s dilemma is that it will have to change its views and accept nuclear weapons to survive, but it believes it cannot survive by accepting them.

So long as this quandary persists, there is no way for NATO to come up with a realistic defense. And perhaps the most dangerously unrealistic thing it can do is to concoct new conventional panaceas to calm down the increasing political discontent over an alliance that now seems headed for oblivion. If the West seriously wishes to defend itself, it will have to resolve its nuclear dilemma rather than displaying new conventional looks that ignore nuclear realities.

—Sam Cohen (inventor of the neutron bomb), September 1983

ACDA’s Impact on Arms Control and Its Role in the Future

Kenneth L. Adelman: The success of arms control itself depends on the maintenance of American strength. Twentyfive years after the founding of ACDA [the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency], arms control is a far larger and more complicated enterprise than it was in those early years, and in some ways a more difficult one. … But 25 years after ACDA’s start, the effort to achieve a real reduction in the nuclear danger has really just begun, and all of us are conscious that we have a long way to go.

George M. Seignious: To prosper in the bureaucratic fray and to keep the support of its constituency behind it, ACDA must seek to maintain momentum in the search for realistic arms-control solutions while protecting its flanks against charges that it is “soft.”

In a similar vein, ACDA, in cooperation with other parts of government, should devote even greater effort to improving our verification capabilities. Greater confidence in compliance will strengthen ACDA’s constituency and increase the viability of the arms-control process. In this regard, we should not only pursue aggressively refinements in our national means of verification but also put the Soviets to the test on their new-found interest in on-site inspection.

—Comments from ACDA directors, September 1986

Lowering the Nuclear Threshold: The Specter of North Korea

If the United States and other concerned governments conclude that North Korea is attempting to evade its commitments under the NPT or its pledges to South Korea not to acquire either nuclear weapons or reprocessing facilities, a decision will confront the world community more daunting by far than last year’s decision to drive Iraq out of Kuwait. For to employ conventional air strikes to preempt North Korean nuclear facilities—assuming most are known—will risk triggering another full-blown Korean War, one potentially far more destructive than in the early 1950s, when 4 million soldiers and civilians lost their lives.

Some military experts believe high-tech conventional weapons, rushed to the scene, would be sufficient to turn back an armored assault. But if South Korea appeared in danger of being overrun, would the United States resort to tactical nuclear weapons? That is hardly the vision of a New World Order that President [George H.W.] Bush had in mind in the afterglow of Desert Storm. But that is a real-world specter, which must be confronted and thought through.

—William Beecher, June 1992

Almost a Success Story

The transition from authoritarian to democratic structures, while having an important positive political impact, also has entailed a deterioration of control over nuclear material. … Reflecting on a half century of living with nuclear weapons, it is remarkable that despite the broad access to nuclear technology, there exist today only five declared nuclear weapon states, three nuclear-capable states and a few others whose nuclear intentions remain uncertain. Much of this can be explained by existence of a nuclear nonproliferation regime anchored on the NPT, leading states to conclude that their security interests are best served by abjuring nuclear weapons.

—Lawrence Scheinman, February 1998

Needed: A New Nuclear Contract

From the beginning of the nuclear era, the U.S. government recognized that in the arena of nuclear weapons, it has no permanent friends, only permanent interests. The United States opposed both British and French acquisition of nuclear weapons. Eisenhower had to deal with the seductive logic of preventive war because it was clear that the Soviet Union, when it reached “atomic plenty,” would be able to inflict massive damage on the United States. Launching an attack on Chinese nuclear facilities, possibly in cahoots with the Soviet Union, was seriously discussed during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. The Clinton administration gave thought to an attack on North Korean nuclear facilities. Yet each American president decided against preventive war. Diplomacy, and time, eventually became the preferred tools of Washington policymakers from both parties in the effort to control proliferation.

—James Goodby, July-August 2007 Focus

A Nuclear Reductions Primer

The significance of the START Followon Treaty extends beyond the bilateral military relationship between the United States and Russia. The deep reductions that it envisions and the concomitant commitment to seek even deeper reductions in the future also respond to international calls for demonstrated progress toward nuclear disarmament. That achievement is expected to enable the United States to lobby the international community more credibly and effectively to strengthen nonproliferation norms and hold violators of those norms accountable.

—Sally K. Horn, December 2009 Focus

What the Iran Nuclear Deal Says about Making Foreign Policy Today

Whether driven by ideology, money or both, the debate over the Iran nuclear issue marked a new low in relations between the Republican majorities in Congress and the Obama administration. It also prompted a remarkable, perhaps unprecedented, level of involvement by groups outside of government. Think-tanks, political advocacy organizations, pro-Israel and religious groups, nonprofit associations, veterans’ groups, media outlets, arms control organizations and others weighed in on both sides of the debate. It was a foreign affairs food fight, with positions both for and against the agreement argued with great passion and intensity.

—Dennis Jett, October 2017