Compassion Fatigue in the Foreign Service

Speaking Out

BY KOVIA GRATZON-ERSKINE

National Counseling Group, Inc.

Whether through terrorism or natural and man-made disasters, tragedy can strike anywhere—there is no longer any such thing as a “normal” post. Whether they deliberately sign up or unexpectedly find themselves in the middle of a crisis, Foreign Service professionals often work during and after disasters like the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the earthquake in Nepal, drought and food insecurity in the Horn of Africa and the Sahel, and complex emergencies in Ukraine and Sri Lanka or the Venezuelan migration into Colombia. In some ways, FS professionals thrive in this environment.

While often rewarding, working in these high-stress, trauma-prone environments can also lead to compassion fatigue (CF). FS professionals and managers at all posts—even in Washington, D.C.—need to understand the risks of CF, recognize the symptoms and implement healthy practices to help protect the workforce.

I Didn’t See It Coming

In 2010, I felt called by a sense of duty to go to Haiti after the massive 7.0 magnitude earthquake killed 200,000 people and left a million more displaced. When I arrived eight months after the initial disaster the lingering effects on staff—both American and Haitian—were clear. Behind their tough exteriors there was fatigue in their eyes. Everyone was working nonstop to get more done, faster and under heavy scrutiny from the media and Washington. Perhaps most importantly, they were driven by their own sense of compassion for others’ suffering.

Things got more intense from there. Several months into my tour, during which protests and tropical storms were a normal part of life, a viral disease broke out in a small village, spreading quickly and killing thousands throughout the country. Embassy staff, myself included, went into overdrive. The new normal was 14-hour days, six days a week.

At first, we worked those hours because we needed to meet the demands. But for me, it soon became compulsive. I felt I couldn’t stop—I worried that even a 15-minute break could cost a life. That’s the effect of empathy boiled over—an inability to take time to eat and sleep, knowing that thousands are suffering without shelter or medical care.

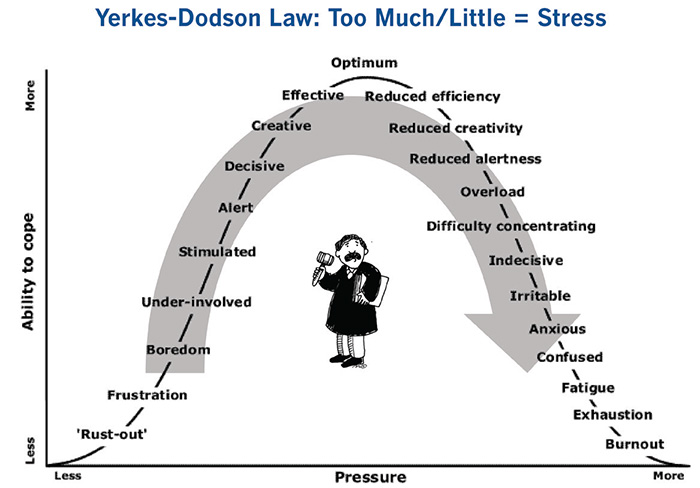

The problem is that unchecked physiological and mental stress impairs performance. The Yerkes-Dodson Law, developed in 1908, posits that stress can improve performance, but only up to a point (see illustration). Both too much and too little stress can negatively affect job performance, satisfaction and health.

In Haiti, I was stimulated by the overwhelming need immediately upon arrival. I’d like to think I worked at my optimum level of efficiency and effectiveness for months, perhaps even a year. But then I slid down the right side of the curve into exhaustion.

What Is Compassion Fatigue?

The same traits that make FS professionals good at their work—empathy, compassion for others and tenacity—can, when self-care is neglected, turn into compassion fatigue.

Sometimes referred to as “secondary post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)” or “vicarious traumatization,” compassion fatigue (CF) is the extreme state of exhaustion experienced by people who have been exposed to trauma through their work to support suffering people or animals. CF does manifest in similar ways to PTSD. Both conditions can result in disassociation or feelings of numbness, detachment/isolation, alcohol or drug abuse, feelings of helplessness or hopelessness, insomnia, nightmares, loss of appetite or binge eating, hypervigilance, and panic attacks.

In me, compassion fatigue started with exhaustion, followed by six months of headaches and an overdose of stress hormones that put my nervous system on high alert. My fight-flight-freeze response was stuck in overdrive, making me constantly jumpy and fearful.

Yet there was a dissonance between these symptoms and what I did for a living. I had an overseas desk job, after all, while CF is considered a risk among people who work more directly in helping capacities like mental health practitioners, law enforcement, emergency medical personnel, and others who deal directly with victims of trauma.

But the signs and symptoms of CF were certainly there. Physical and emotional exhaustion (“burnout”)—check. Bombardment with grim images and stories of colleagues and Haitian citizens (indirect exposure to trauma)—check. Despite this, the drive to help led me to overextend and neglect myself for more than a year.

There was a dissonance between these symptoms and what I did for a living. I had an overseas desk job, after all.

It’s a Matter of Time

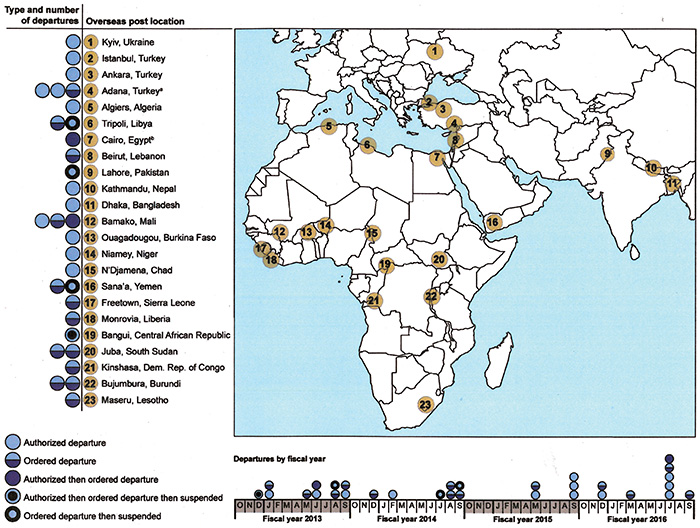

Aid workers and diplomats regularly encounter situations that may elicit unhealthy stress levels. For example, between October 2012 and September 2016 the State Department managed 31 evacuations from 23 overseas posts (see map below). Hundreds of Foreign Service families have been affected—and global events that cause disruption show no sign of slowing.

A September 2015 report commissioned by USAID found that “the USAID workforce is currently exposed to severe levels of stress and is at risk for developing numerous stress-related health conditions and/or disorders.” Institutional stress is exacerbated, the researchers found, by threat exposure, operational tempo and political pressure—three things USAID personnel working in critical priority countries, non-permissive environments and high-threat posts experience regularly.

The State Department is addressing this new reality by expanding the Foreign Affairs Counter Threat training program, which was once reserved for FS professionals working in high-threat, high-risk countries, to include those assigned to every post by the end of this year.

While FACT and the high-threat security overseas seminar equip FS professionals and their families with the skills needed to react in high-threat situations, they do not prepare them for the mental and psychological demands of living through crisis after crisis. This is a gap that both USAID and State are attempting to fill.

The USAID Staff Care Center was established in 2012 to manage an Employee Assistance Program with wide-ranging benefits (e.g., childcare subsidy, elder care, fitness facility access) available to both domestic and overseas staff members. In addition to counseling and psychosocial support, the SCC offers organizational resilience training.

In 2016 the Department of State created the Center of Excellence in Foreign Affairs Resilience. Located at the Foreign Service Institute, CEFAR provides training and other resources to all FS professionals. CEFAR also integrates resilience-focused content into training for both new and seasoned professionals.

State’s Bureau of Medical Services, CEFAR and SCC offer safety nets; but, as they say, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Extend Compassion to Yourself and Your Team

While PTSD and other mental health issues have become expected and accepted in the military, FS professionals seldom talk about it. The silence stems from fears of medical clearances being revoked and careers derailed, but there is also a societal perception that PTSD only affects veterans or victims of abuse. In fact, observing or supporting others who have experienced a traumatic event—something FS professionals do on a regular basis—can also lead to PTSD, secondary PTSD or compassion fatigue.

Preventing CF requires effort on both a personal and an institutional level. While institutions need to support employees who are exposed to trauma, FS members, especially managers, need to be aware that the risk of CF is inherent in the work they do. Individuals can apply preventive measures through several key approaches. They need to recognize the symptoms and adapt their work habits and those of their employees as needed. They need to proactively work to create a healthy work environment at post to reduce the risk of developing CF. And they need to encourage self-care to enhance overall health and well-being.

Here are some steps I’ve learned that help me sustain a healthy lifestyle even while working in high-pressure and trauma-prone environments:

Practice basic self-care. If I’m feeling off, these practices can help immediately. I need to: Get a full night’s sleep (seven to eight hours). Work out four to five times a week. Eat well and regularly—at least three times a day, plus snacks. Stay hydrated—drink two liters of water or herbal tea a day. Be social (play with kids, go out with friends). Give my brain a break (try meditation, crosswords or Sudoku) and use mindfulness (try yoga, stretching and proper breathing techniques; ground my thoughts in the present instead of focusing on future worries and past regrets).

Create boundaries and balance. This is easier said than done, but I learned that having the right mindset will help keep me on track. Toward that end, I commit myself to taking breaks during the workday and leaving at a reasonable hour—and truly leaving my work, including thinking about work, behind.

Know thyself. Intentionally reflecting on how I’m doing can reduce the risk of living in a prolonged state of stress without proper care. When I do periodic check-ins with myself, I notice my anxiety levels, sleeping patterns, anger reactions, eating habits, weight gain or loss, and headaches or backaches. If something is off kilter, I return to basic self-care techniques. If that’s not enough, I see a doctor or therapist.

Look out for each other. I know I cannot always see the problem. So, in addition to paying attention to the physical and mental state of friends and colleagues, I can: Recognize signs and symptoms of irritation or depression; encourage activities to reduce stress; and regularly share information about support services with others at post.

Be an effective leader. If I’m the boss, I remind my staff to leave the office at a reasonable hour and to rest their brains, exercise, eat and have some fun. I’ve learned that it takes more than encouragement; leaders must model healthy workplace behaviors to show that these actions are acceptable.

It’s Up to You

Compassion for others is a beautiful thing, but it must be accompanied by compassion for self. After leaving Haiti, I spent a couple years decompressing in a lower-stress D.C. position before returning to more intense work, such as the Ebola outbreak recovery and rebuilding efforts in West Africa. Through a commitment to my own well-being, the symptoms of CF have subsided, and I make sure to continue my own self-care and communicate openly about the risks of failing to do so.

FSOs work in high-pressure environments in places subject to corruption, poverty, sickness and disaster. It’s only a matter of time before you or a family member serves in a difficult place, and it’s hard not to feel the effects. Watch for symptoms of compassion fatigue, in yourself and in those around you. Show leadership in supporting a healthy work environment. And take breaks and ask for help when you need it. You’ll be better positioned to fulfill your mission as a Foreign Service professional.

Read More...

- “Are You Suffering from Compassion Fatigue?”

- “What is Compassion Fatigue?” –Compassion Fatigue Awareness Project

- “Compassion Fatigue” –American Institute of Stress