Groundbreaking Diplomacy: An Interview with George Shultz

George Shultz reflects on his tenure as Secretary of State in the Reagan administration and the process of making foreign policy and conducting diplomacy during the decade leading up to the fall of the Soviet Union.

BY JAMES E. GOODBY

Editor’s Note: George P. Shultz is an economist and Republican presidential adviser best known for serving as Secretary of State under Ronald Reagan. He joined the Nixon administration in 1969 and served as secretary of Labor, director of the Office of Management and Budget, and secretary of the Treasury. Shultz was president of Bechtel and an economic adviser to President Ronald Reagan when he was tapped to replace Alexander Haig as Secretary of State in 1982. He served for the remainder of Reagan’s time in office, and was awarded the Medal of Freedom by Ronald Reagan in 1989.

The Foreign Service Journal is pleased to publish this transcript of James E. Goodby’s interview with the former Secretary of State. The interview was conducted in October 2015 in connection with a study at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution on governance in America, but it was never published. The general theme of their conversation is how Secretary Shultz perceived his service to President Ronald Reagan, whom he served for six years, and the Secretary’s reflections on President Reagan’s approach to strategic thinking.

At a working session at Hofdi House during the Reykjavík Summit, October 1986. From left: General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev, an interpreter, USSR Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze, U.S. President Ronald Reagan, U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz.

Courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

James E. Goodby: Mr. Secretary, we have talked before about your role as Secretary of State in the Reagan administration. What I would like to do is sound you out about Ronald Reagan, about presidents, and about your relations with the White House. I would like to begin by quoting something from your 1993 memoir, Turmoil and Triumph. In it, you said something that struck me very forcefully: that Reagan, like any president, had his flaws and strengths, and the job of an adviser was to build on his strengths and try to help him overcome whatever flaws he might have. What struck me about that observation was that it was rather similar to something that Secretary of State Dean Acheson wrote about his relationship with President Harry Truman.

George Shultz: I think the Secretary of State needs to have the same attitude any other Cabinet officer does. People would ask me what my foreign policy was, and I always said, “I do not have one; the president has one. My job is to help him formulate it and carry it out, but it is the president’s foreign policy.” So I think you need to be clear about who is the guy who got elected.

However, I had something special that President Reagan suggested himself. We had twice-weekly private meetings,just the two of us. Of course, we would talk about whatever he wanted to talk about, and I always had an agenda of my own. We tried to look over the horizon and not make any decisions, but in the process, I got to know him very well. I think that in all of my early associations with him, which went back quite a bit before I became his Secretary of State, we had managed to build between us (and also between Nancy and me) a relationship of trust. He knew that I would tell him what I thought, and he also knew that I knew it was his foreign policy, not mine. So we had good conversations, but underneath it all was trust.

One of the outstanding things about President Reagan was his consistency and the way he handled himself. People trusted him. Here is an example. One time [German Chancellor] Helmut Kohl came to Washington about four months before the president was to go to Germany. Kohl said, “When [French President François] Mitterrand and I went to a cemetery where French and German soldiers were buried, we had a handshake. It was publicized and was very good for both of us. You are coming to Germany, Mr. President; would you come to a cemetery and do the same thing?”

President Reagan agreed. Then the Germans sent word they had picked the cemetery, a place called Bitburg, and someWhite House person did a little checking and said OK. But once they shoveled the snow off the gravestones and discovered SS troops were buried there, all hell broke loose.

I remember Elie Wiesel came to the White House and said, “Mr. President, your place is not with the SS; your place is with the victims of the SS.” It was lots of pressure. We tried to get the Germans to change the site. We made a lot of suggestions for alternatives, and they would not change. So, in the end, he went.

After that, he went home and I went to Israel to be the speaker at the unveiling of the outdoor Yad Vashem [Israel’s official Holocaust memorial]. When I came back to Washington, I stopped in London for a talk with [British Prime Minister] Margaret Thatcher. She said to me, “You know, there is not another leader in the free world that would have taken the political beating at home your president took to deliver on a promise that he made. But one thing you can be sure of with Ronald Reagan: If he gives you his word, that is it.”

And that is a very important thing to establish: that you are good for your word.

DoD did not like the idea of negotiating, but President Reagan did. … And in the fall of 1985 we had the big meeting in Geneva between President Reagan and then-Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev.

JEG: Another thing you said in your memoir is that it is not just having strength that gives an advantage to a nation, but knowing what to do with it. President Reagan was ready to negotiate [with the Soviets], but some of his advisers were not so ready. You backed him up, and that contributed to his strength. I presume you thought that he would be as successful as he was with your support. Could you tell us a little about that part of it?

GS: I have always felt that strength and diplomacy go together. If you go to a negotiation and you do not have any strength, you are going to get your head handed to you. On the other hand, the willingness to negotiate builds strength because you are using it for a constructive purpose. If it is strength with no objective to be gained, it loses its meaning. So I think they go together. These are not alternative ways of going about things.

JEG: You have also said that there is a tendency in Washington to go to one extreme or the other, either to all military strength or to all diplomacy, and that the task of blending the two together is very difficult. Can you give us some real-life examples of that from the Reagan administration?

GS: Actually, I don’t think it is difficult. I think it is like breathing. Of course, they go together. There is no other way. When I went into the job of Secretary of State, our relations with the Soviet Union were almost non-existent, very strained. President Jimmy Carter had cut off nearly all ties after they invaded Afghanistan, and it was still tense.

I’d had quite a lot of experience in dealing with the Soviets when I was Secretary of the Treasury. I had worked out quite a few deals and spent time there. So I managed to negotiate. I worked a deal to meet with Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador to the United States, once a week. The object was to resolve little irritants so they did not grow into big problems.

In early 1983, I returned to Andrews Air Force Base from a visit to China on a Friday morning, and it was snowing so hard I was lucky to land. It snowed all day Friday, Friday night and into Saturday morning. So the Reagans are stuck in the White House. They cannot go to Camp David. Our phone rings, and Nancy says, “How about you and your wife come over for supper?” The four of us sit around, we are having a good time, and they start asking me about the Chinese leaders. What kind of people are they? Do they have a bottom line? Can you find a bottom line? Do they have a sense of humor? And so on.

Then they knew I had dealt with the Soviets when I was at Treasury, so they started asking me about them. A lot of them were still in office. All of a sudden, it dawns on me: This man has never had a real conversation with a big-time communist leader, and he is dying to have one.

So I said to him, “Next Tuesday at 5, Ambassador Dobrynin is coming in for one of my regular sessions. What if I bring him over here and you talk to him?” He said that would be great, and it will not take long, just 10 minutes. All I want to tell him is that if their new leader, Yuri Andropov (who had just succeeded Leonid Brezhnev), is interested in a constructive conversation, then I am ready.”

President Reagan and I both thought that foreign policy starts in your own neighborhood. If you have a strong, cohesive neighborhood, you have a much better base then, if something goes wrong.

That attitude was totally different from the atmosphere that people thought existed. The White House staff tried to kill the meeting, but the president had decided he wanted to have it, so we did. We were in there for at least an hour and a half, and Reagan talked about everything under the sun. About a third of the time, he talked about Soviet Jewry and how they were being mistreated.

Then he brought up the Pentecostals. Do you remember during the Carter administration, a group of them had rushed our embassy in Moscow? They had not been allowed to emigrate or worship the way they wanted, and we could not expel them from the building because they would probably be killed, but it was a very uncomfortable thing. President Reagan kept saying, “It is like a big neon sign in Moscow saying, ‘We do not treat people right. We do not let them worship the way they want.’ You ought to do something about it.”

Dobrynin and I were riding back to the State Department afterward, and we agreed, “Hey, let us make this our special project.” So we exchanged memos back and forth. Finally, I got one that was pretty good, and I brought it over to the White House. I said, “Mr. President, any lawyer would say that you could drive a truck through the holes in this memo, but I have to believe after all this background, that if we get them to leave the embassy, they will be allowed to go home and eventually emigrate.” We talked about it and decided to roll the dice. All the time the president talked about Soviet Jewry, and he just said, “I want something to happen. I will not say a word about credit. I just want something to happen.”

So we got the Pentecostals to leave the embassy. They were allowed to go home. A couple of months later, they were all allowed to emigrate along with their families, around 60 people. I said to the president, “The deal is: ‘we’ll let them go if you don’t crow.’” And he never said a word.

I’ve always thought this little incident, which was unknown, had some important implications. What Reagan learned was you can make a deal with these people, and even if it is kind of fuzzy, they will carry it out. And they learned the same thing. They knew how tempting it is for American politicians to say: Look what my predecessor did, and now look what I did. But President Reagan did not do that, so you could trust him. You could deal with him. You can deal with somebody you trust. You cannot deal with somebody you do not trust. It is very hard.

On the other hand, then there was a huge buildup of Soviet strength because—as you remember, Jim; you were involved in it—the Soviets deployed their SS-20 missiles, intermediate range, aimed at Europe. The diplomatic idea was if they attacked Europe with intermediate-range missiles, we would use our intercontinental missiles to retaliate, thereby bringing a retaliatory strike on us. That is how they were hoping to divide Europe from the United States.

We had a deal with NATO that we would negotiate with the Soviets, and if we could not reach a satisfactory conclusion, we would deploy our own intermediate-range missiles. We had a hard negotiation. At one point, the Soviets shot down a Korean airliner and we led the charge in condemning them.

We had a transcript of the Soviet pilot in contact with his ground control and some time elapsed. It showed that they consulted and they gave the pilot the go-ahead to shoot down the airliner. We read all this out. At the same time, stunning the hardline people, we sent our negotiators back to Geneva, and I went on with a meeting I had scheduled with [Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei] Gromyko. All this was, in part, to convince the European public that we were negotiating energetically.

I tell myself not to look at my inbox; instead, I go sit in a comfortable chair with a pad and a pencil, take a deep breath, and ask myself: “What am I doing here? What are our strategic objectives and how are we doing?”

After the meeting, the interpreter, who had interpreted for a lot of meetings between Secretaries of State and Soviet foreign ministers, said it was the most bitter, contentious meeting he had ever seen. But it registered on Gromyko what we thought. The point is, we did deploy the cruise missiles in Britain and Italy, and then ballistic missiles in Germany, and it was a huge thing. The Soviets walked out of negotiations, and fanned war talk, but we stood up to it.

Early in 1984, we had a coordinated approach. President Reagan gave kind of a high-level, reasonably friendly speech, and I had a more operational one in a meeting which Gromyko and I attended in Stockholm that January. We were not yelling at each other. It was sort of constructive, and it was a huge moment.

Then, as time went on, things gradually cooled off a little. I was out here at Stanford for summer vacation, and the president was in Los Angeles. I went down there for a meeting and asked him for a little private time. I said, “Mr. President, at three or four of our embassies in Europe, a Soviet diplomat has come up to one of ours and he said virtually the same thing, which we think boils down to this: If Gromyko is invited to Washington when he comes to the United Nations in September, he will accept. Mr. President, you may want to think it over because President Carter canceled those meetings when they went into Afghanistan, and they are still there.” Reagan replied, “I do not have to think it over. Let’s get him here.”

In other words, the Soviets blinked. So Gromyko came, and it was a good meeting, with an interesting little sideline. I had a good relationship with Nancy Reagan and said to her, “Nancy, the routine here is he comes to the West Wing, we have a meeting in the Oval Office, and we walk down the colonnade to the mansion for some stand-around time. Then there is a working lunch. How about you being there during the stand-around time, since this is your home and you are the hostess?” She agreed.

We walked down there, Gromyko sees Nancy, and he goes right after her. At one point—and you know Nancy can bristle—Gromyko said, “Does your husband want peace?” Nancy bristled, “Of course, my husband wants peace.” Then Gromyko says, “Please whisper it in his ear every night before he goes to sleep: ‘peace.’”

He was a little taller than she was, so she put her hand on his shoulder and pulled him down so he had to bend his knee, and she said: “I will whisper it in your ear: peace.”

Anyway, after the 1984 election, which President Reagan won by a landslide, we resumed our meetings in Geneva from a position of strength. Our economy was really moving by that time, and we had built up our military strength. And the showdown over the INF missiles put us in a good position to negotiate.

Then along comes [Mikhail] Gorbachev. All of the preceding is pre-Gorbachev. I remember going over there with the U.S. delegation for the Andropov funeral. The president had given me a few things to say, but Vice President [George H.W.] Bush was there as the delegation head.

President Reagan knew that I would tell him what I thought, and he also knew that I knew it was his foreign policy, not mine. So we had good conversations, but underneath it all was trust.

We were one of the last delegations to meet with Gorbachev. We met for over an hour. He had all these notes in front of him, but he shuffled them around and never looked at them. I had just a few things to say, which I said, and then I had the luxury of watching. Afterward, I said to our people, this is a different kind of man than any Soviet leader we have ever dealt with: more nimble. He is smarter, better informed. Still a hard-edge communist, but you can talk to him. He listens and then he answers, and he expects you to listen and answer back, and have a conversation. Usually, you say something, it goes by my ear, and I say something, it goes by your ear—and that is not a conversation. With Gorbachev, you can engage.

And that was how our negotiations started: from a position of strength. We knew what we wanted, we were strong, and we negotiated.

JEG: You and President Reagan had a very clear view of what you wanted to accomplish. You had trust between you and yet, as you mentioned earlier, there were people in the White House who did not agree with what you both wanted to do. So that makes me wonder how Secretaries of State, in general, manage to get and keep a president’s ear in spite of all of these other pressures to do something else. What is the secret of your success in this? To quote another striking line from your memoir: “I learned to exercise responsibility in a sea of uncertain authority.” How did you manage that?

GS: I think I would rewrite that line now, because there was no uncertain authority. The president was the authority, I had my meetings with him, and I had my insight from that long evening about where his instincts were. So that gave me the basis for proceeding, but there was a huge analytical difference of opinion in Washington. There were people who thought basically the Soviet Union was there and they would never really change.

Reagan had a different idea. If you read his Westminster speech in 1982, it is very striking because he thought they were basically weak, and they would in the end change if we were strong enough in deterrence. I think George F. Kennan in his Long Telegram said something similar: If we can contain the Soviets long enough, they will look inward; they will not like what they see, and they will change.

And for my part, I had a lot of experience with the Soviets when I was Treasury Secretary and saw the deficiencies in their system. So, for all those reasons, I thought they would change.

The CIA people were really focused on military hardware and did not think change was possible. DoD did not like the idea of negotiating, but President Reagan did. So we had some back and forth, and in the fall of 1985 we had the big meeting in Geneva between President Reagan and then-Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev. I remember [Defense Secretary Caspar] “Cap” Weinberger opposed the meeting and tried to sabotage it, but he did not succeed. Out of that meeting came this phrase that President Reagan had already used in his State of the Union message: “A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” That was a big statement from those two leaders, and it was the start of bringing the numbers of nuclear weapons down.

U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz (right) greeting new Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze at the White House, Sept. 27, 1985. From left: Eduard Shevardnadze, interpreter Pavel Palazhchenko, President Ronald Reagan, George Shultz.

Courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

JEG: In your memoir, you talk about how each president has many more advisers than his predecessors, and they often quarrel with one another and get into fights that the principals often are not even aware of. Would you like to elaborate on that?

GS: Well, it seems to me when you try to make policy and carry out policy entirely in the White House, you do not have access to the career people and you do not really use your Cabinet to full advantage. You wind up not having the right players, and policy is not as good, and is not carried out as well.

I remember when General Colin Powell became national security adviser. I knew him pretty well, and he came over to my office and he said, “George, I am here to tell you I am a member of your staff.” I told him that was an interesting statement. He explained: “The National Security Council consists of the President, the Vice President, the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Defense; and that National Security Council has a staff; and I am the Chief of that Staff. Obviously, the President is my most important client, but I am working for the whole National Security Council.”

Colin had the right idea. When the Reagan administration was leaving office, he came to a ceremony in my honor and he said, “The chief of staff of the National Security Council and the Secretary of State have not gotten along so well since Henry Kissinger held both jobs simultaneously.”

JEG: How would you describe the general approach to foreign policy you and President Reagan followed?

GS: President Reagan and I both thought that foreign policy starts in your own neighborhood. If you have a strong, cohesive neighborhood, you have a much better base then, if something goes wrong. I remember my first trip out of the country as Secretary of State was to Canada and the traveling press was saying, what in the world are you doing going there?

I replied, “Who do you think our biggest trading partner is?” They all said Germany or Britain or something. One said Japan. I said they were out of their mind: Add all those up together and it does not come to as much as Canada.

My second trip out of the country was to Mexico, and we tried to lay the foundation for what eventually came together as the North American Free Trade Agreement. We first had to get an agreement with Canada; then Mexico came in. But, anyway, it was not just the Soviet Union; we had a strategy for North America. We paid a lot of attention to South America, Central America and the Asia-Pacific region, as well. And we had strategies for each of those regions.

A second principle we followed was this: You have to think you are a global power. That is one of the reasons why the Foreign Service is so important: so you have people of professional quality who cover the globe. That’s why, when I hear the idea that we are going to pivot to Asia or something like that, I say it does not sound right to me. We need a global diplomacy. We have to be there, everywhere. Of course, you shift your focus a little bit depending on where the action is.

If you plant a garden and go away for six months, what have you got when you come back? Weeds. Diplomacy is kind of like that. You go around and talk to people, you develop a relationship of trust and confidence, and then if something comes up, you have that base to work from.

JEG: You have written that you very consciously set about finding time in your schedule to think about where you were going and what you needed to do. That seems to be one of the shortcomings that we have had in Washington throughout the years. People usually do not do that. They let the urgent drive out the important. Is there any way you can encourage people to think a bit more instead of frenetically traveling around the world?

GS: In the State Department you have a group of people whose job is to think: the Policy Planning staff. I always felt—and this goes way back to my time in other Cabinet positions, and for that matter in business—that you tend to be inundated with tactical problems. Stuff is happening all the time and you are dealing with it. So I developed the idea that at least twice a week—in prime time, not the end of the day when you are tired—I take, say, three-quarters of an hour or so and tell my secretary: If my wife calls or the president calls, put them through; otherwise, no calls.

I tell myself not to look at my inbox; instead, I go sit in a comfortable chair with a pad and a pencil, take a deep breath, and ask myself: “What am I doing here? What are our strategic objectives and how are we doing?” Reflecting on that has helped me quite a lot, I think.

A lot of this goes back to the process of governance, which has gotten way out of kilter because there is too much White House and National Security Council staff, and not enough consultation with Cabinet people. But there are other problems, too. These days, if you take the job of assistant secretary of State for something or other, you get presented with a stack of paper an inch thick that you need an accountant and a lawyer to help you fill out. Then the Senate takes its time before holding a hearing. And after all that, they may never vote on your nomination. At the end of the 113th Congress, there were 133 nominees who had been reported out favorably but not voted on, so they had to flop over to the next Congress.

That is not the way you recruit A-players.

JEG: I’d like to wind up with a couple of questions about how Secretaries of State relate to Congress. How do you see the relationship? What is the responsibility of the Secretary in terms of selling the president’s policies to Congress? And does that process work, or can it be improved?

GS: Different people do it different ways, but you have to spend a lot of time with members of Congress. For one thing, they have good ideas. So if you listen to them, you might just learn something. As you remember, Jim, we had congressional observers come over to Geneva for our negotiations with the Soviet Union. We got the INF Treaty ratified as a result, something many people thought was impossible. But we did it.

We did not take Congress for granted. We had brought all the negotiating records back and stored them in a secure room. We had one of the negotiators there all the time to answer questions, and we not only gave formal testimony, but held a lot of informal meetings. There was a lot of opposition, but in the end the treaty was ratified 93 to 5. So our efforts to cultivate Capitol Hill paid off, and we learned from it.

If you develop trust, you develop the ability to have frank conversations, and that helps.

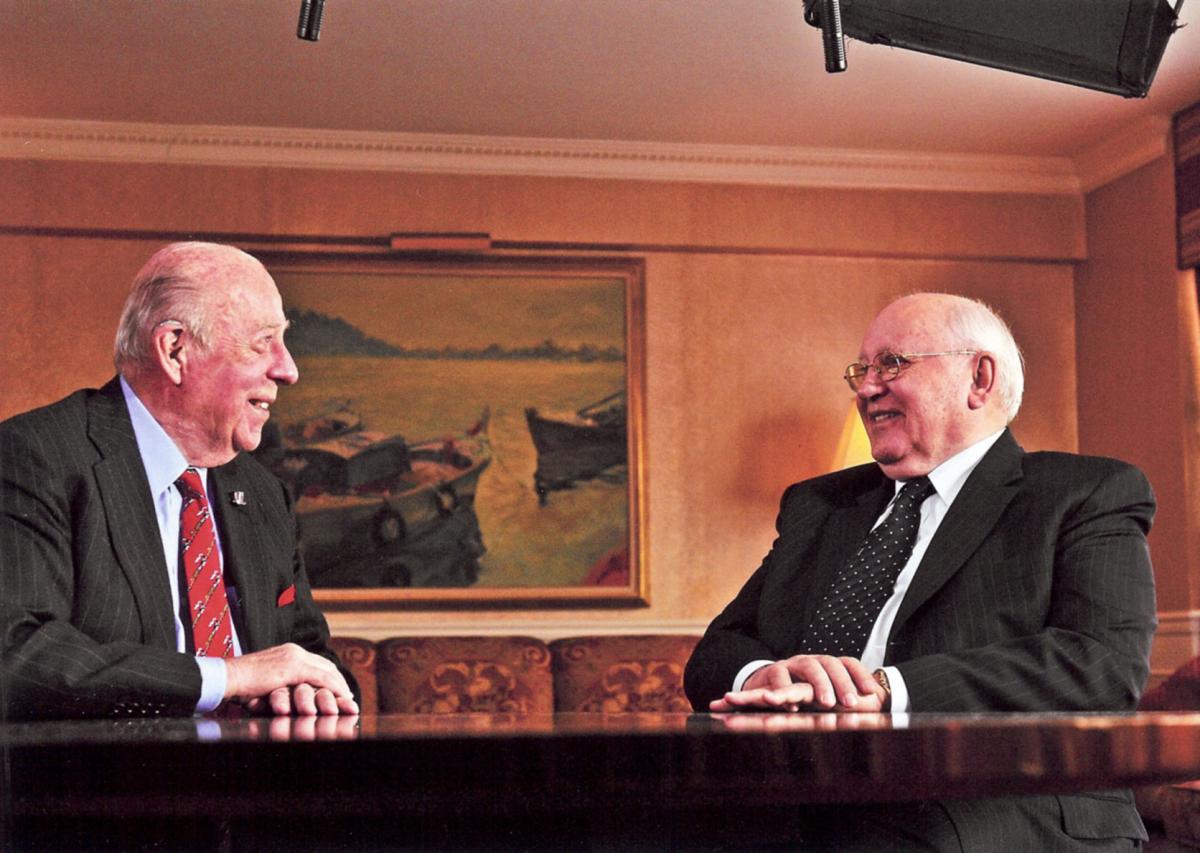

George Shultz and Mikhail Gorbachev meeting in New York City on March 24, 2009, to look back on the U.S.-Soviet exchanges of the late 1980s. The conversation was recorded for use in a three-part television series on the life of George Shultz, Turmoil and Triumph.

Courtesy of Free to Choose Network

JEG: This reminds me that you have compared diplomacy to gardening: keeping down the weeds and cultivating relationships.

GS: Yes, the analogy is if you plant a garden and go away for six months, what have you got when you come back? Weeds. And any good gardener knows you have to clear the weeds out right away.

Diplomacy is kind of like that. You go around and talk to people, you develop a relationship of trust and confidence, and then if something comes up, you have that base to work from. If you have never seen somebody before and you are trying to work a delicate, difficult problem, it is hard.

For example, I got to know Wu Xueqian, who was the Chinese foreign minister, and we had a good relationship. I remember him saying to me once: “OK, George, you wanted to get to this point and you are trying to go about it in a certain way. That way is very hard for us, but if you can come at it in a little different way, we can get where you want to go.” I said, fine, and we did. But that kind of progress does not happen unless you have gardened.

JEG: Let me end by asking you about one more quote from your memoir: “Public service is something special, more an opportunity and a privilege than an obligation.” Do you feel the same way today in light of everything that has happened since you wrote that 20 years ago?

GS: Oh, yes! I have had an academic career and a business career, both very exciting and worthwhile. But if I look back on my government career, that is the highlight, because I can think back to things I was involved in that made a difference. Really, that’s what your life is about: You are trying to make a difference. And you can do that in public life in a way that is hard to do otherwise.

JEG: Thank you, Mr. Secretary. I appreciate this very much.

GS: Well, I am a Marine, so I say, “Semper Fi.”

JEG: Semper Fi! Thank you.