Pitching In to Do Vital Work

A distinguished ambassador describes work in the world of refugee resettlement.

BY JOHNNY YOUNG

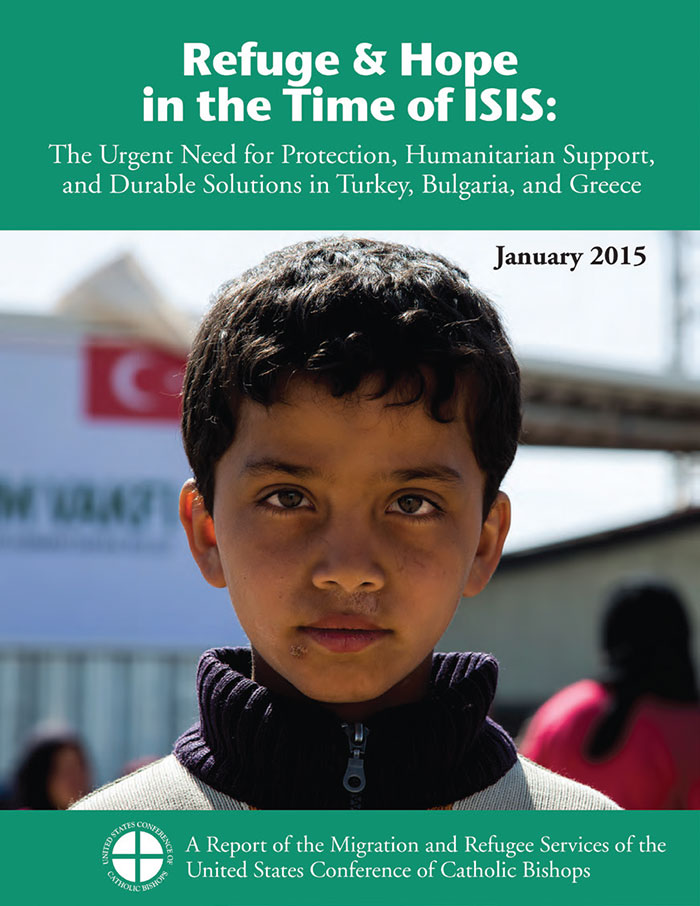

This January 2015 report assesses the unprecedented refugee crisis erupting from the Syria conflict.

U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops

When I retired from the Senior Foreign Service in 2004, after a 38-year career, I vowed that I would only return to full-time work if I could “do good.” An opportunity to do just that came in August 2007, when I accepted an offer to become executive director for migration and refugee services at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

In that position, which I held until February 2015, I managed the world’s largest nongovernmental resettlement agency. The Office of Migration and Refugee Services has a budget of more than $80 million, a staff of 106, and more than 80 affiliate resettlement offices across the United States.

MRS, as I will refer to it here, is one of nine faith-based and secular organizations that partner with the State Department and the Department of Health and Human Services to resettle and assist refugees. To give you an idea of how vital its work is, I’ll note that of the 70,000 refugees the U.S. government admitted in 2014, MRS resettled more than 16,000—nearly a quarter of the total.

The process begins overseas when the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees interviews a prospective refugee and determines that he or she meets the criteria to be designated a refugee, and can neither return home nor remain in the country of asylum. Candidates approved for resettlement in a third country must undergo an extensive series of clearances and multiple security checks, which typically take between 18 and 24 months for those coming to the United States. Only then may the refugee travel to the country of referral.

Of the millions of refugees in camps and urban areas around the world, only about 1 percent may be selected for resettlement each year.

Work on Many Fronts at Home and Abroad

It was clear to me from my first day on the job at MRS that I had entered an incredible world of exceptionally dedicated, hard-working professionals who are totally committed to the best interest of refugees. This world included my immediate colleagues at MRS and contacts and colleagues from the broader refugee resettlement community, including the network of U.S government agencies and offices. The role of all of these players in refugee work is not just to protect refugees, but to offer them hope and a second chance at a normal life.

My responsibilities at MRS encompassed several areas. First and foremost was managing our headquarters and its affiliates so we could continue to process refugees for resettlement fairly, efficiently and cost-effectively. During my tenure, our budget increased from $50 million to $80 million, primarily for programmatic increases to assist refugees at higher levels of allowance, something for which we had vigorously advocated.

We also regularly traveled overseas, often to dangerous locales, to assess the extent of refugee problems and recommend groups for consideration for resettlement in the United States. During a series of trips to the Middle East I took between 2007 and 2014, we found an increasingly horrific situation. We repeatedly reported that refugee flows in the region would only mount until peace returned to the region. Sadly, our testimony largely fell on deaf ears.

My team’s report following a trip to Bulgaria, Turkey and Greece in the fall of 2014 (“Refuge and Hope in the Time of ISIS”) described the unfolding crisis in stark terms:

“The escalating Syrian conflict has created one of the worst refugee crises of our generation. When a Committee on Migration delegation previously traveled to Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey in October 2012, some 550,000 people had fled from Syria’s 18-month old conflict. According to UNHCR, with Syria now in its fourth year of conflict that number exceeds 3.8 million. Syrians now make up the world’s largest refugee population after the Palestinians. Half of Syrian refugees are children. Over 85 percent live outside of refugee camps in towns and villages of the host countries.

During a series of trips to the Middle East I took between 2007 and 2014, we found an increasingly horrific situation.

“Besides producing high numbers of refugees, Syria has some 7.6 million internally displaced people (IDP) and Iraq an estimated 1.9 million. An estimated 191,369 Syrians have been killed in the conflict. … Islamic State of Iraq and Syria has further worsened and expanded the crisis to involve Iraqis and growing numbers of ethnic and religious minorities. During the first several days of the Committee on Migration’s [current] assessment trip, over 130,000 Kurdish Syrians from Kobane and surrounding villages in northern Syria were forced by ISIS to flee into Turkey. Besides illustrating the escalating forced migration from Syria, the large influx of this ethnic minority illustrates the growing complexity of the conflict.”

Turkey’s towns and cities were being overwhelmed, and its capacity for processing refugees and providing them protection and basic services challenged, the report notes. Explaining this, MRS went on to identify promising interventions and suggest practical solutions in the areas of increasing refugee registration capacity, disseminating information to refugees on processes and services, and opening opportunities for refugee schooling and work.

Yet as grim as we found the situation at that time, we did not foresee the magnitude of the current Syrian refugee flow into Europe—much less the delayed, tepid U.S. response.

Advocacy Work

I also joined resettlement coalitions and partners in a wide range of meetings and advocacy efforts. These centered on remaining true to our core principles: to protect refugees and give those allowed to resettle in the United States a second chance.

These meetings involved counterparts, as well as senior officials, at the departments of State, Homeland Security and HHS, and even the White House. We also did a lot of advocacy on Capitol Hill. Regardless of how big or small the interaction, these meetings consistently focused on promoting the well-being of refugees and safeguarding the integrity of the refugee program. We took on such subjects as funding, the number of refugees allowed into our country, and the resolution of problems some state and local governments created to hinder resettlement programs in their jurisdictions. We were generally very successful in these efforts.

Of my many domestic duties, I most enjoyed visiting our affiliate offices across the United States, and meeting with refugee families during those visits. Some of them had suffered years, if not decades, of impoverishment and indignities as they awaited resettlement. Their gratitude reaffirmed my already deep appreciation for the U.S. resettlement program, which offers the possibility of a green card and a pathway to citizenship.

I will never forget one Iraqi family—husband, wife and three children under 10—in Albuquerque, New Mexico, that had been in the country for only a few months. Because of her excellent English prior to coming to the United States, the wife had reversed roles with her husband and become the leader of the family. She was the only breadwinner and was the interface with the community and service providers. The couple struggled with this situation. But what struck me even more was how the wife kept repeating, over and over, how happy they were that the kids could play freely outside and there were no bombs. No bombs. No bombs! She felt secure, protected and free—the core objective of the resettlement program.

Since 1975 the United States has welcomed more than three million refugees from all over the world who have built new lives in cities and towns across the country. Of the approximately 15.4 million refugees in the world today, the vast majority will receive support in the country to which they fled. Less than one percent are eventually resettled in a third country, and of those the United States welcomes more than half—more than all other resettlement countries combined.

Still, there is no doubt in my mind that our country can and should do much more, especially for Syrians and other refugees. I pray that our leaders will not be distracted by the idle chatter of ill-informed politicians who use the refugee resettlement program as a pawn in their political games and schemes. Instead, let us remain firm in our support for refugee resettlement programs, which reflect who we are as a people and what we believe in.

Read More...

- Frequently Asked Questions about Refugees (UNHCR)

- Resettlement: A New Beginning in a Third Country (UNHCR)

- 8 Facts about the U.S. Program to Resettle Syrian Refugees by Teresa Welsh (U.S. News & World Report)

- How to help Syrian refugees? These groups you may not know are doing important work by Jared Goyette (PRI)

- How to help in a global refugee crisis by Tara Siegel Bernard (The New York Times)