The Island Hopper

A classic diplomatic courier mission across the Pacific recalls the history of World War II.

BY JAMES B. ANGELL

Jeff Lau

Pohnpei Island’s Nan Madol archaeological site, shown here, was home to the Saudeleur Dynasty from 1100 to 1600. During World War II, Japanese defenses on the island were so strong that the U.S. chose to drop 118 tons of bombs on it rather than invade.

en.wikigogo.org

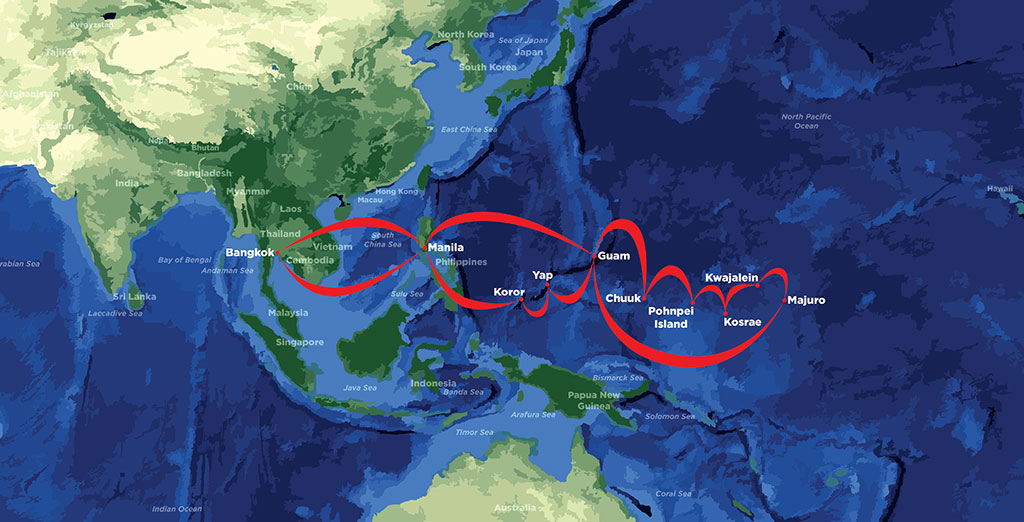

One of the classic diplomatic courier missions is the Bangkok Regional Diplomatic Courier Division’s “Island Hopper,” a 10,000-mile round trip that stretches across the planet from Bangkok to Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands on the International Date Line, and back. It is also a mission that encompasses much of the Pacific theater of World War II.

Setting up the logistics for such a trip takes days of work weeks ahead of time, with a detailed cable sent to multiple personnel, at both State and Defense and at six U.S. missions stretching across the Pacific. The inbound classified diplomatic pouch information for each post is confirmed in the cable, and posts are requested to inform the Bangkok office of their classified dispatch to ensure efficient scheduling. Once all U.S. entities have been informed, the mission can proceed.

Getting the classified pouches planeside without being X-rayed is not an issue in Bangkok, as our relationship with Thai Customs & Immigration couldn’t be better. The cleared American escort takes the material directly onto the tarmac while I process through the terminal like any other passenger, paying for the excess diplomatic pouch weight before arriving at the gate.

With the assistance of Thai Air staff and an airport badge, it’s routine to descend to the tarmac to meet the escort planeside for a piece count and to observe the diplomatic pouches being loaded into the aircraft. With the escort securing the hold, I’m free to board the aircraft via the air bridge.

East to Manila

Taking off to the south from Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport with a belly load of classified diplomatic pouches, the flight soars over Samut Prakan. It was there, on Dec. 8, 1941, that the 3rd Battalion of the Japanese Imperial Guards Regiment came ashore with orders to take Bangkok. But after a tense standoff with a Thai Police detachment, they agreed to wait for formal negotiations to conclude before fighting their way to the capital. There were five other Japanese landing sites further south along the Gulf of Thailand that morning, and many confrontations with Thai resistance resulted in casualties on both sides.

A favorite contemporary image of Guam is the Japanese pillbox under towering hotels on Tumon Beach.

The invasion was all part of the larger Japanese strategy of quickly seizing the Malay Peninsula, Singapore and Burma from the British. On Dec. 21 of that year, a formal alliance was signed between Bangkok and Tokyo allowing Japan access to Thailand’s infrastructure to launch cross-border attacks. On Jan. 25, 1942, Thailand’s Field Marshall Phibun formally declared war against the United States and Britain.

This Japanese gun emplacement on Tumon Beach in Guam is a World War II relic.

Jiro Waters

Interestingly, Thailand’s ambassador to the United States, Seni Promoj, not only refused to deliver Field Marshall Phibun’s declaration of war to the State Department, but began to organize the Free Thai (Seri Thai) movement (in cooperation with the Office of Strategic Services) that helped liberate the country three years later.

Three hours after departing Thailand, my flight begins its descent over the entrance to Manila Bay, directly above Corregidor, scene of one of the most humiliating surrenders in American history. To the north is the Bataan Peninsula, crowned by the craggy 4,554-foot Mariveles Volcano that towers over Corregidor. Looking south out of the right window, one sees Cavite province, where the Japanese began their bombardment of U.S. forces on the island on Feb. 8, 1942.

During the final approach into Manila, I can clearly see the World War II American Military Cemetery, a circular 152-acre park containing 36,285 American dead, one of our largest overseas military graveyards. Most of the casualties occurred during the New Guinea, Philippine, China, Burma and India campaigns.

Corregidor fell on May 6, 1942, after Lt. General Wainwright’s radio message to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared: “There is a limit of human endurance, and that point has been long passed.” Through the invasion of the Philippines, the Japanese were able to isolate the archipelago from resupply and gain important airfields for operational thrusts throughout the Pacific.

On to Guam

After an exchange of classified diplomatic pouches with embassy personnel on the tarmac at Manila’s Ninoy Aquino Airport, a complex change of aircraft for the subsequent journey to Guam takes place. As a result of increased security at airports worldwide, signing for classified material, changing airlines, paying excess baggage and moving the diplomatic pouches from one plane to another are never easy. Only Embassy Manila’s excellent support at the airport makes this transit possible.

The Americans’ Operation Hailstone destroyed 249 aircraft and sank 12 warships and 32 merchant ships, turning Chuuk Lagoon into the largest graveyard of ships in the world.

Three hours later, on the approach into Guam, I can see the sawgrass hills of the island fringed by reefs in a single glance. Because Guam is American territory, the security at the airport is tighter than elsewhere in the region. The diplomatic courier is not allowed to descend planeside at Won Pat International Airport to retrieve our classified material, so a second courier is sent from Bangkok ahead of time to act as a cleared escort.

The wreck of the Japanese submarine Shinohara in Chuuk Lagoon. This sub was part of the fleet that attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

johncollins.ie

Merely securing an airport badge ahead of time isn’t enough to access the tarmac, however; the escort has to be joined by a U.S. Transportation Security Administration employee planeside. After a successful exchange of classified diplomatic pouches with another government agency, the remaining material is driven 30 minutes north to Andersen Air Base for secure overnight storage along a flight line crowded with B-52s. The interagency cooperation between the Diplomatic Courier Service and the U.S. Air Force on Guam is seamless.

A favorite contemporary image of Guam is the Japanese pillbox under towering hotels on Tumon Beach. Japanese tourists are the dominant economic force on the island today. The irony of them lounging on the beach around this World War II relic belies the fierce fight their countrymen put up against returning American forces. Numerous former machine-gun emplacements chiseled from coral can still be found along the jungle beaches north of Tumon, perfectly positioned to rake the shore approaches of an invading force. But the Americans didn’t strike here, but further south at Asan Beach in 1944, in what is now the War in the Pacific National Park, the westernmost Department of Interior monument.

I spend a day off on Guam exploring Japanese gun emplacements buried deep in bamboo thickets and visiting the isolated Talafofo River Valley, where Sgt. Soichi Yokoi lived hidden for 28 years. When discovered in 1972, he had exclaimed: “We Japanese soldiers were told to prefer death to the disgrace of being captured alive.”

The Real Thing

The Island Hopper mission truly begins, however, on the spectacular flight from Guam into Chuuk (Truk), the first stop on the United Airlines 737 route that services five islands on the way to Hawaii. After Chuuk comes Pohnpei Island, Kosrae, Kwajalein and then Majuro, capital of the Marshall Islands.

Chuuk is one of the largest atolls in the world, with a protective reef 140 miles around. Since there is no U.S. mission there, I remain planeside for an hour to guard the classified pouches in the hold. This is ample time to soak in the scenery and contemplate the history of this remote locale.

Initially part of the Spanish Empire, the Caroline Islands became German after the Spanish-American War. They were then ceded to Japan by the League of Nations’ South Pacific Mandate after the defeat of Germany in World War I. Known as the Gibraltar of the Pacific, Chuuk was the Empire of Japan’s main base in the South Pacific. Its garrison consisted of 50,000 Japanese military personnel with the lagoon harboring most of its Pacific fleet.

With Majuro’s capture, the United States gained one of the largest anchorages in the Pacific.

In 1944, the Americans’ Operation Hailstone, launched from the recently invaded Marshall Islands 1,500 miles to the east, became one of the most effective airstrikes of the war. It destroyed 249 aircraft and sank 12 warships and 32 merchant ships, turning Chuuk Lagoon into the largest graveyard of ships in the world. In the poetic justice category, it is interesting to note that one of the relics in the lagoon is the submarine Shinohara, part of the fleet that attacked Pearl Harbor, which was hit when it attempted a dive to avoid attack.

Majuro, Marshall Islands. When U.S. forces invaded on Jan. 30, 1944, they found that the Japanese already evacuated to Kwajalein.

ds-lands.com

After takeoff from Chuuk, with spectacular views of the reef and islands, an hourlong hop to Pohnpei Island, for an exchange of classified diplomatic pouches with the small embassy in Kolonia, is next. Even though the capital of the Federated States of Micronesia is now in the town of Palikir, just down the road to the southwest, most embassies remain in Kolonia. Because the Japanese had built up their defenses on the island so thoroughly during their rule, the Americans chose to drop 118 tons of bombs on this stronghold rather than invade it. Even though Pohnpei was bypassed during the amphibious campaign, remnants of the bombing campaign are littered throughout the island.

On takeoff from Pohnpei, I get a glimpse of the archaeological site of Nan Madol, home of the Saudeleur Dynasty from 1100 to 1600, in the distance along the eastern side of the island. This site is composed of megalithic structures and funerary sites. It is said the founders of this dynasty came from afar and looked nothing like the native people; but they did set up an organized government, unifying Pohnpeians for the first time.

In the Marshall Islands

After a day of island hopping from Guam, the flight finally touches down on the 50-yard-wide airstrip on the 30-mile-long atoll in Majuro, capital of the Marshall Islands. As the aircraft taxis to the quaint terminal, I see lagoon out one window and surf out the other. It’s a fairly casual arrival in keeping with the relaxed nature of the islands.

The cleared embassy escort meets me planeside and takes me immediately to the chancery. The embassy is small enough that the ambassador or deputy chief of mission typically drops by for a chat during the sign-over of classified pouches.

On Jan. 30, 1944, when U.S. forces invaded, they discovered that the Japanese, who had managed the island since 1922, had already evacuated to Kwajalein. With Majuro’s capture, the United States gained one of the largest anchorages in the Pacific. It became one of the busiest ports in the world until the action moved further west during the latter part of the war.

After spending 47 days adrift when his bomber crashed in the South Pacific, bombardier Louis Zamperini (the focus of a best-selling novel, Unbroken) was captured by the Japanese off the Marshall Islands’ seaplane base of Wotje in June 1943. He was then moved to Kwajalein as a prisoner of war before being transferred to the POW camp in Ofuna, Japan, by ship via Chuuk, a few months later. The nearly seven weeks Zamperini spent floating in the Pacific surrounded by sharks and the subsequent six weeks of imprisonment on Kwajalein were halcyon days compared with what awaited him on the Japanese mainland.

After a restful night on Majuro under a blizzard of stars, it’s time to head to the embassy to pick up the post’s outbound shipment. The flight, which arrives from Honolulu, retraces the previous day’s route back to Guam. Another long day of island hopping concludes with a drive to Andersen Air Base for storage and an overnight in Guam. Early the following morning, all regional outbound classified diplomatic pouches are consolidated and dispatched to Manila via Yap and Koror.

The Republic of Palau

The Manila flight continues southwest from Yap toward Koror, part of the Republic of Palau, the westernmost cluster of Caroline Islands. All these islands, including Yap, were also part of the League of Nations Mandate that granted control to the Japanese after World War I.

In January 1945, when American and Philippine forces attempted to recapture Manila, they drove the retreating Japanese troops into the walled city and shelled it.

Koror itself, where the embassy is located, is currently staffed by an ambassador and a few officers. It was not directly involved in World War II hostilities, but the battle for the nearby island of Peleliu is still remembered as one of the bloodiest of the Pacific campaign. Operation Stalemate II finally ended in the autumn of 1944 after 2,000 Americans and 10,000 Japanese were killed.

Intramuros in Manila, as it looked in January 1945.

en.wikigogo.org

An airport exchange of classified diplomatic pouches occurs here with an embassy escort. An hour later the plane is taxiing for a takeoff over the spectacular Rock Islands, shaped like mushrooms rising from turquoise waters.

After a few hours in the air, we fly past the perfect cone of the Mayon Volcano (8,081 feet) and over the Leyte Gulf, scene of the largest naval battle in modern history. In October 1944, this was the site of General Douglas MacArthur’s famous “I have returned” speech to the Philippine people. The Battle of Leyte Gulf pitted 212 Allied ships against the remnants of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The victory there eventually paved the way for American and Philippine troops to recapture the Bataan Peninsula on Feb. 17, 1945. In Manila, I secure the regional classified material overnight in the embassy vault, and proceed to explore the disheveled seafront and Intramuros District, the original walled Spanish settlement built in 1571.

In January 1945, when American and Philippine forces attempted to recapture Manila, they drove the retreating Japanese troops into the walled city and shelled it, killing 16,000 soldiers. The infamous Manila Massacre, committed by Imperial Japanese Army troops while surrounded by U.S. and Philippine forces, killed some 100,000 Filipinos—10 percent of the city’s population at the time.

The next morning it’s important that I arrive at the airport early. Embassy Manila always has a large outbound classified load, and traffic is notoriously bad. The diplomatic courier escort in Manila always does an excellent job of getting the pouches planeside through a remote customs gate. I process through the terminal like a regular passenger, before being escorted onto the tarmac to observe their loading by the Thai ground agent.

Following wheels-up, the flight soars west over Corregidor. En route to Bangkok above the South China Sea, we pass over Scarborough Shoal and the Paracel Islands—two contentious island groups currently being claimed by the Chinese, much to the displeasure of the Philippines and Vietnam.

On arrival in Bangkok, the entire classified load of diplomatic pouches is securely transferred from Suvarnabhumi Airport to the embassy’s classified vault, where it is prepared for dispatch aboard the weekly department trunk line to Seoul and Washington.

The Island Hopper is a classic Diplomatic Courier Service trip, as well as an education in the history of the Western Pacific during World War II.