How Refugee Resettlement in the United States Actually Works

Historically, the United States has permanently resettled more refugees than all other countries combined. Here’s what’s involved.

BY CAROL COLLOTON

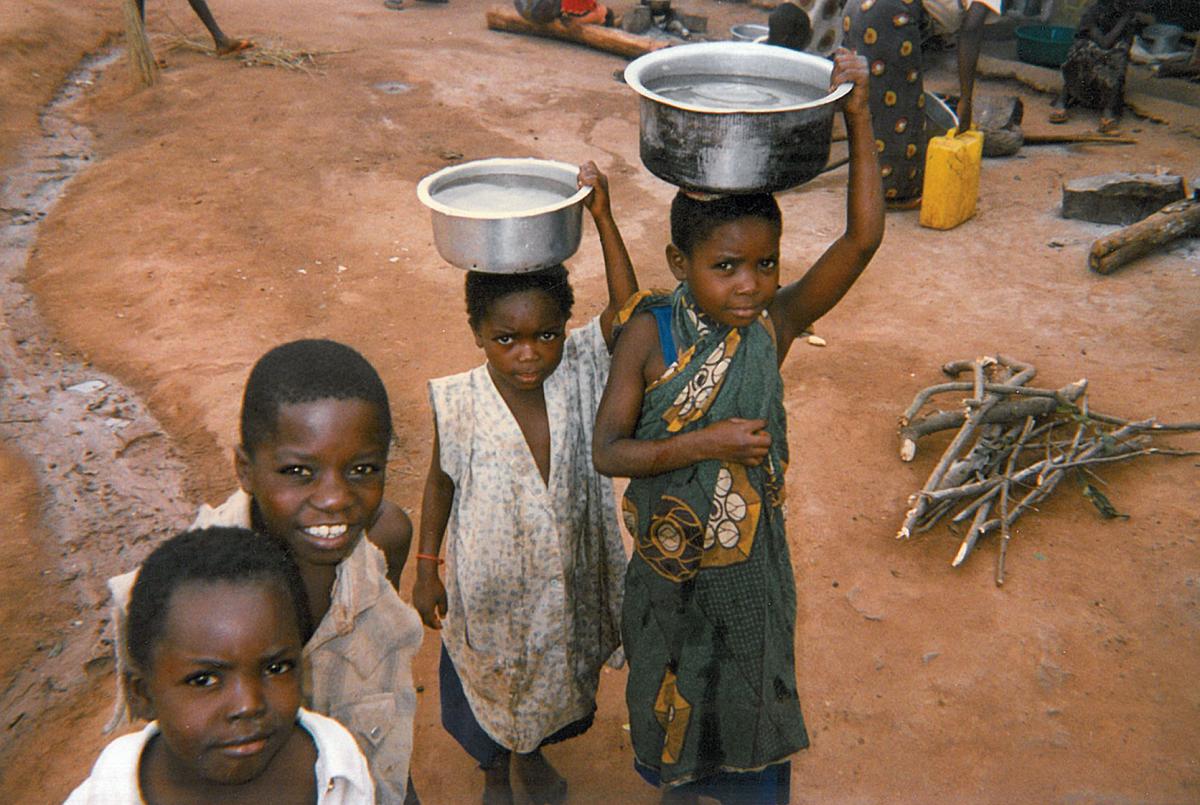

Young children at a Tanzanian refugee camp during the 1990s civil war in Rwanda.

Carol Colloton

Aisha arrived at Kennedy Airport on a rainy afternoon in November 2009 looking more than a little apprehensive as she clutched her two small children and a number of mismatched bags holding their personal belongings. Four years earlier, she had fled her village in Rwanda and ended up in a refugee camp in the Democratic Republic of the Congo run by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. There she awaited resettlement in a third country.

She filled out reams of application forms, provided biographical data, and sat for interviews with representatives of the Resettlement Support Center and numerous security officials, followed by medical exams. When she was finally told that the United States had accepted her application, it was like a dream come true. But it was not until she had a departure date, and started attending cultural orientation classes, that the reality sank in: she was actually going to America!

Aisha was suddenly beset with doubts. She didn’t know a soul in America; how would she survive? Maybe she should just stay in the camp, she thought. But with everyone congratulating her and telling her how lucky she was, she put on a brave face and reminded herself of the violent events she had lived through, and the anguish of the years since leaving Rwanda behind. Right now her most pressing concern was hiding from her children her fear of getting on an airplane for the first time in her life.

She was reassured when she was greeted in New York City by a representative of Church World Services, who assisted her family in transiting the airport and boarding another plane to Minneapolis. There, the local CWS sponsor escorted them to a two-bedroom apartment. It was a bitterly cold, snowy day in December; they had never seen snow before.

Of the millions of refugees in the world, who should be selected for resettlement?

Then things began to happen at a bewildering pace. The sponsor explained how the stove, heating system and smoke alarm worked, and took Aisha and her children to a church basement so they could pick out warm clothes. Other CWS staff explained U.S. currency, showed her around the neighborhood, and pointed out where and how to shop, and how to take the local bus. The children were registered in school, doctors’ appointments were made, and she was enrolled in English-language classes and a job search program.

Seven years later, Aisha has a job cleaning offices. Her children are picking up English much faster than she, and she often relies on them when they go shopping or visit a doctor. After a year, she received the coveted green card giving her permanent residency and was beginning to feel comfortable in the United States. She hoped and prayed that her sister and her children would soon be able to join her. But then, following last summer’s bombings in Paris, Aisha began hearing that many Americans wanted to keep any more refugees from coming.

Aisha’s experience is far from unique in both respects. But that does not mean the hostility toward refugees and legal migrants shown by some Americans who got here earlier in our history is any less pleasant.

The Role of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees

People, of course, have migrated throughout human history for various reasons: fleeing war and violence, or seeking a better life economically, politically and socially. But with the advent of the nation-state system, and the demarcation of defined borders, governments began to regulate such mass movements more closely—particularly the flow of refugees, a specific category of migrants governed by international agreements.

To be precise, under international law refugees—as distinguished from internally displaced persons, or IDPs, who have been uprooted from their homes but remain in their country—are defined as “individuals who have fled from their country of nationality or habitual residence, having a well-founded fear of persecution because of their race, religion, nationality or membership in a particular social or political group, and owing to such fear are unable or unwilling to return to that country.” The first step for a person fleeing his or her own country is to seek refuge in a neighboring country—in international parlance, the country of first asylum. A refugee is thereby distinguished from an individual who applies to immigrate via the visa application process.

Current practices for admitting refugees date from the post-World War II period. Some 146 countries adopted the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees that entered into force on April 20, 1954, and was limited to persons fleeing events occurring before Jan. 1, 1951, within Europe. A 1967 protocol removed those limitations and expanded the Convention to universal coverage. Pursuant to these measures, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees based in Geneva, Switzerland, is the focal point for regularization and international coordination of such efforts.

Whenever there is a large-scale movement of people, national and international nongovernmental agencies, assisted by the UNHCR, concentrate on quickly setting up emergency shelter, food, water, sanitation and medical services. Only then do they focus on screening individuals to determine if they qualify for refugee status. Once the refugees’ physical needs are met and refugee status determined, more stable conditions are established. Some refugees live among the local population, while others have families in neighboring countries.

The screening process for refugees is far more rigorous than for any other group entering the United States.

The objective then becomes a durable solution. Ideally, refugees will return to their homeland as soon as the situation allows. Lamentably, all too often this outcome is prevented by continuing political unrest, or the fact that the refugees belong to a minority ethnic or religious group that remains unwelcome. The next-best solution is for them to be settled in the country of first asylum and integrated into its society. But in some relatively few cases, third-country resettlement may be the best option.

Of the millions of refugees in the world, who should be selected for resettlement? In 2006, UNHCR designated broad priority categories for refugee resettlement, such as: survivors of violence or torture, family reunification, medical needs, and women and children at risk. Within these categories, narrower designations were established to respond to specific situations and to apply to specific countries. For example, the category used for resettlement of Liberians to the United States was “women-at-risk”—older women who were raising their grandchildren because the parents had died, either from violence or from diseases such as malaria and HIV/AIDS. Another was “The Lost Boys,” young Sudanese who had become separated from their families during their flight from the fighting in the south of Sudan and were resettled in the United States in 2001. Following the Rwandan genocide, “mixed marriage” refugees—Hutu and Tutsi—were identified as “at risk,” but the Rwandan government objected to the implication that such families could not reside peacefully in postwar Rwanda.

Is the American Commitment to Aid Refugees Fading?

Historically, the United States has permanently resettled more refugees than all other countries combined. In 1980, the year of highest U.S. resettlement, Congress set an annual ceiling of 207,000 arrivals. This number has gone up and down through the years in response to different periods of unrest leading to increased population migrations as well as to domestic political pressures. From 2008 to 2011, the ceiling was set at 80,000, but not met. Since 2013, the ceiling has been established at 70,000 and has been more or less fulfilled each year.

Recent terrorist attacks have led to calls to bar or severely limit the number of new refugees entering the United States. But such proposals ignore the fact that the screening process for refugees is far more rigorous than for any other group entering the United States (generally taking between 18 and 21 months of vetting). Further, the U.S. government can refuse entry to any foreigner, including a refugee, without cause.

Once individuals are identified as eligible for resettlement they all go through the intensive screening process, as did Aisha mentioned above, conducted by the UNHCR, international voluntary agencies and, for those considered for entry into the United States, representatives of the State Department, the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security. This involves collecting biographical data, medical clearances and intensive security screening.

The majority of refugees are normally resettled in 15 states: California (which takes nearly 16 percent), followed by Washington (just under 15 percent), New York (nearly 9 percent), Florida (7 percent), North Carolina and Texas (5 percent each). Oregon, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Georgia and Arizona each accept just over 3 percent of refugees, while Missouri, Massachusetts, Minnesota and Ohio account for about 2 percent each.

While about 30 state government officials have declared their intention to reject the settlement of any Syrian refugees in their states, it is worth noting that most of those states take few if any refugees to begin with—and the three states accepting the largest numbers have all reaffirmed their participation in resettlement programs.

How Local Resettlement Works

Some U.S. critics of refugee resettlement have claimed that the federal government settles refugees in their states without consultation. This is not the case, however. While only the federal government can determine whether or not a refugee may be admitted to the country, federal law requires consultation with state and local governments on the resettlement of refugees in a particular community.

Fortunately, the State Department and the Department of Health and Human Services have traditionally enjoyed a cooperative, constructive relationship with state and local refugee coordinators and with voluntary agencies in determining where to place refugees.

The plight of millions of refugees encapsulates many aspects of international relations the world appears to be unprepared, or unwilling, to deal with.

The nine voluntary agencies active in resettling refugees in the United States work closely with their local affiliates and state refugee coordinators to determine which locations are the best match for the communities and the refugees. The following factors are considered: family reunification; the number of refugees already in the state and in a particular community (the objective is to avoid overwhelming an area with large numbers, but also to settle refugees where compatriots are already residing); and the availability of affordable housing, employment opportunities, and health and educational facilities.

There have been instances in which a state or local community has objected to resettlement in a particular locality for various reasons. Even if they do not agree that those reasons are valid, the federal government and voluntary agencies generally accede to such objections. After what these refugees have already been put through, the last thing they need is more hostility.

A Problem That Is Not Going Away

The plight of millions of refugees encapsulates many aspects of international relations the world appears to be unprepared, or unwilling, to deal with.

Currently, there are nearly 20 million refugees in the world (not including some five million Palestinians). Whole generations are growing up in what are supposedly “temporary” camps. The international governmental agencies and NGOs running them have to build, staff and supply medical clinics, schools and other basic services.

In response, some countries that have not traditionally been resettlement havens have either begun accepting refugees or taking more of them. Several European countries have increased the number of refugees they accept; others have taken in large numbers in proportion to their population. Finland, for example, with a population of about 5.5 million, has accepted 750 refugees a year since 2001 and planned to take in 1,050 in each of 2014 and 2015. Still, this generosity does little to meet the overall needs.

Are we at a major turning point in human history? With international communications and commercial entities dwarfing the power of most governments, we might well ask ourselves whether the nation-state system as we know it is at a point of cataclysmic change. While climate change is not yet a designated qualification for granting refugee status, its impact may well swallow up small island nations and low-lying coastal areas of many countries—setting off chaotic, uncontrollable mass movements beyond anything we have seen thus far.

Let us hope that international diplomatic efforts will succeed in reducing if not eliminating armed conflicts, and international agreements on human rights, economic trade and other international exchanges will narrow the huge gaps between the haves and have-nots. But even in a best-case scenario, we can probably expect continuing mass movements of people across international borders for the foreseeable future. So a firm American commitment to assisting and resettling them remains essential.

Read More...

- Refugee Resettlement in the United States

- Refugees and Asylees in the United States by Jie Zone and Jeanne Batalova (Migration Policy Institute)

- Frequently Asked Questions: Refugee Resettlement (U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants)