2021 Award for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy: A Conversation with John D. Negroponte

Ambassador John D. Negroponte is the 2021 Recipient of the Award for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy.

John Negroponte in a helicopter in Vietnam when he was a provincial reporting officer at Embassy Saigon, 1964.

Courtesy of John D. Negroponte

Ambassador John D. Negroponte, a former Deputy Secretary of State and a five-time chief of mission, is this year’s recipient of the American Foreign Service Association’s Award for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy. (For coverage of the ceremony, see AFSA News, p. 63.) He is the 27th recipient of this prestigious award, given annually in recognition of a distinguished practitioner’s career and enduring devotion to diplomacy. Past honorees include George H.W. Bush, Thomas Pickering, Ruth Davis, George Shultz, Richard Lugar, Joan Clark, Ronald Neumann, Sam Nunn, Rozanne Ridgway, Nancy Powell, Thomas Boyatt, William Harrop, Herman “Hank” Cohen and Edward Perkins.

John D. Negroponte was born in London, England, on July 21, 1939, and raised in New York City. He received a bachelor’s degree from Yale University after graduating from Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. Following a brief period at Harvard Law School, he joined the U.S. Foreign Service in 1960. His initial overseas postings included Hong Kong, Vietnam, France (as a staffer at the Paris Peace Talks), Ecuador and Greece. Stateside, he served in the Bureau of African Affairs, was a State Department Fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution and twice served on the National Security Council.

In addition to serving as a deputy assistant secretary of State (1977-1979), deputy assistant secretary in the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs (1980-1981), assistant secretary in the Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs (1985-1987) and deputy national security adviser to the National Security Council (1987-1989), Ambassador Negroponte was chief of mission in Honduras (1981-1985), Mexico (1989-1993) and the Philippines (1993-1996).

After serving as a special representative to what was then the Bureau of American Republics Affairs (now the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs), Ambassador Negroponte retired from the Foreign Service in 1997 and worked for McGraw-Hill Companies as executive vice president for global markets for four years. In 2001, President George W. Bush summoned Amb. Negroponte back to public service as U.S. Permanent Representative to the United Nations (2001-2004) and ambassador to Iraq (2004-2005). Appointments as Director of National Intelligence (2005-2007) and Deputy Secretary of State (2007-2009) followed, before Amb. Negroponte retired from government service.

John Negroponte as a novice skier in Sun Valley, Idaho, 1941.

Courtesy of John D. Negroponte

During his Foreign Service career, Amb. Negroponte received the highest award that can be conferred by the Secretary of State, the State Department Secretary’s Distinguished Service Award, on two occasions. In 2005, he received the Raymond “Jit” Trainor Award for Distinction in the Conduct of Diplomacy from Georgetown University’s Institute for the Study of Diplomacy. In 2006, he won the American Academy of Achievement’s Golden Plate Award as well as the George F. Kennan Award for Distinguished Public Service from the National Committee on American Foreign Policy. And in January 2009, President George W. Bush personally conferred the National Security Medal on Amb. Negroponte.

After retirement, Amb. Negroponte received two additional awards for his invaluable contributions to diplomacy. In 2014, the American Committees on Foreign Relations presented him with its Distinguished Service Award for the Advancement of Public Discourse in Foreign Policy. And in 2019, the American Academy of Diplomacy chose him for its Walter and Leonore Annenberg Award for Excellence in Diplomacy.

Amb. Negroponte taught international relations at Yale’s Jackson Institute from 2009 to 2016 and again in 2020-2021. He taught at the Elliott School of International Affairs at The George Washington University from 2016 to 2018, and from 2018 to 2019 was the James R. Schlesinger Distinguished Professor at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. Negroponte is now an adjunct professor at Georgetown University.

Amb. Negroponte serves as chairman emeritus of the Council of the Americas/Americas Society and co-chairman of the U.S.-Philippines Society. He is a past member of the Secretary of State’s Foreign Affairs Policy Board and has also served as chairman of the Intelligence and National Security Alliance.

Amb. Negroponte is married to Diana Villiers Negroponte, the author of Master Negotiator: The Role of James A. Baker, III at the End of the Cold War (Archway Publishing, 2020) and Seeking Peace in El Salvador: The Struggle to Reconstruct a Nation at the End of the Cold War (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). They have five children.

FSJ Editor-in-Chief Shawn Dorman conducted the following interview with Amb. Negroponte via email in September.

From left: FSO David Engel, the interpreter; John Negroponte, liaison officer with the North Vietnamese delegation; and co-leaders of the U.S. Delegation to the Paris Peace Talks on Vietnam, Ambassadors Cyrus Vance and W. Averell Harriman, at a secret meeting with North Vietnamese negotiators Le Duc Tho and Xuan Thuy in 1968.

U.S. Department of State

Becoming a Diplomat and the Early Days

John Negroponte, then National Security Council director for Vietnam, with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in June 1972 during NSC Adviser Henry Kissinger’s visit to Beijing.

Xinhua News Agency

FSJ: I understand that you decided to pursue a diplomatic career while in high school. What was the catalyst for that decision?

Amb. John Negroponte: I was much influenced by my father who had studied diplomacy in Paris during the 1930s but then, owing to the war, was unable to go forward with his plans to join the Greek diplomatic service. We came to the United States instead when I was an infant. But my dad definitely had a passion for foreign policy issues, and they were a part of our regular conversation, even at a very early age. Along with that, my parents were very international in perspective and spoke several foreign languages, and I became very accustomed to their international friends visiting our home in New York City.

FSJ: What was notable about joining the Foreign Service in the 1960s?

JDN: Government service was popular. Many of my classmates joined the military. Others joined the Central Intelligence Agency. Several of us joined the Foreign Service. The Cold War was in full swing. We were in a real international competition with the Soviet Union. It was palpable.

FSJ: What do you recall about the orientation and training of that time?

JDN: We had eight weeks of basic training, including a week at the Commerce Department. We were taught that trade promotion was a key part of our work, contrary to the legend that State Department FSOs disdain commercial work. That was a myth promoted by those who wanted to take the commercial function away from State, which eventually happened. That was a big mistake.

After the A-100 course, I took consular training in preparation for my assignment to Consulate General Hong Kong. The course was superb. One of the star teachers was Frank Auerbach, a legendary head of the State Department Visa Office. I recall being impressed that Mr. Auerbach had a personal meeting with each and every one of us going out to do visa work. He was the best.

FSJ: For many FSOs of your generation, Vietnam was a searing experience. You did an early tour there. How was that for you, and how did it shape your career?

JDN: My Vietnam experience was very much career-defining. It was not just one tour. It was about four in a row, starting with language training at FSI in 1963-1964, then a 3-1/2 year tour at Embassy Saigon (with TDYs at our consulate in Hue), followed by the Paris Peace Talks on Vietnam and ending as director for Vietnam on Dr. Kissinger’s National Security Council from 1971 to 1973, roughly a decade. Being director for Vietnam on the NSC was the most difficult and challenging position I ever had.

During an NSC briefing on Dec. 9, 1988, President Ronald Reagan and his top advisers watched TV news on Israel’s move into Lebanon. From left: President Reagan, Deputy White House Chief of Staff M.B. Oglesby Jr., Vice President George H.W. Bush (seated), White House Chief of Staff Kenneth Duberstein, National Security Adviser Colin Powell (in foreground) and Deputy National Security Adviser John Negroponte.

The Color Archives / Alamy

Overseas Assignments

FSJ: In your ADST oral history, you say you learned a “cardinal” lesson from your time in Vietnam: “Don’t overuse U.S. military forces. Use local capacity.” How did you apply that to Iraq when you were ambassador there in 2004-2005? And could that have been applied more effectively in Afghanistan over the past 20 years?

JDN: This is an extremely important issue. In my experience, developing local capabilities has often been something of an afterthought in these conflict situations. In Vietnam, for example, during the first four years of combat involvement by our forces, we seemed to want to do all the fighting. The intellectual proponent of this approach was General William Westmoreland, the military commander. I remember attending a Mission Council meeting in Saigon chaired by Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker, when Westmoreland briefed us on his approach. He said he wanted the U.S. forces out in front facing the North Vietnamese forces, while the Saigon army and other forces would defend the populated areas. I remember thinking then that this was a prescription for keeping U.S. combat forces in Vietnam in large numbers for much longer than we needed to.

Westmoreland’s approach was changed by his successor, General Creighton Abrams Jr., in 1968, when we adopted the “Vietnamization Program.” It was long overdue; by the early 1970s the Saigon army had acquitted itself quite well in some very difficult situations. Saigon was ultimately defeated by a conventional invasion from the North with Soviet tanks. We chose not to come to their assistance.

As ambassador to Iraq, I certainly carried some of the lessons I felt I had learned in Vietnam. One of them was the lesson of Vietnamization. When I arrived in Baghdad, there were two or three battalions left in the entire Iraqi army. We had a $17 billion reconstruction program on the books and none of it dedicated to rebuilding the Iraqi armed forces. I persuaded Washington to reprogram about $2 billion of those dollars to train and equip the Iraqi army and police forces. It turned out to be a slow and uneven process; but I have no doubt that Iraq is better able to stand on its feet today because of what we spent then and later to empower their armed forces.

In Afghanistan, we made the same mistake as we did in Vietnam. We started the program of training and equipping their army several years too late, and it was a more challenging task than in Vietnam.

Amb. Negroponte (center) with Secretary of State James Baker (at right) and National Security Staffer FSO Don Johnson (second from left) at an Oval Office meeting with President George H.W. Bush to discuss getting the president’s approval to pursue the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1990.

Courtesy of John D. Negroponte

FSJ: Most of your assignments were in Latin America or Asia. How did you come to specialize in those regions? Was that a choice or more based on the needs of the Service?

JDN: It was a combination. But basically, I never planned my career beyond my next assignment. And some assignments were almost random. For example, I was beginning an assignment in the Africa Bureau in the summer of 1963, as a post management officer. I pretty quickly concluded that wasn’t for me and sought help from my personnel officer. At first he said there was nothing else available since the assignment cycle was complete. A couple of weeks later, he called me up to ask if I would be interested in volunteering for 44 weeks of Vietnamese language training since things were heating up over there; I agreed to do it, and it transformed my career.

FSJ: What was your favorite posting and why?

JDN: We loved Mexico City, where I was ambassador from June 1989 to September 1993. The family loved it. We traveled extensively, managing to visit every state in the country, and we made lasting friendships. On the substantive side, there was a lot to do, and we achieved the North American Free Trade Agreement on my watch.

FSJ: You took on some tough assignments during your career. Looking back on your time as U.S. ambassador to Honduras, in particular, do you have any regrets about the Reagan administration’s support for the Contras?

JDN: Not really. First of all, I had very lively exchanges with Washington about how to pursue our objectives in Central America, and I feel my views always got a fair hearing. Second, Congress cut off funding for the Contras fairly early on. In any event, the Sandinistas lost the presidential election in 1990 to Violeta Chamorro. Some would say that her victory was the result, in part at least, of our having supported a democracy and freedom agenda in Nicaragua.

I would add that it is hard to be too critical of Ronald Reagan’s approach when you see what an absolutely terrible job Daniel Ortega is doing in Nicaragua today.

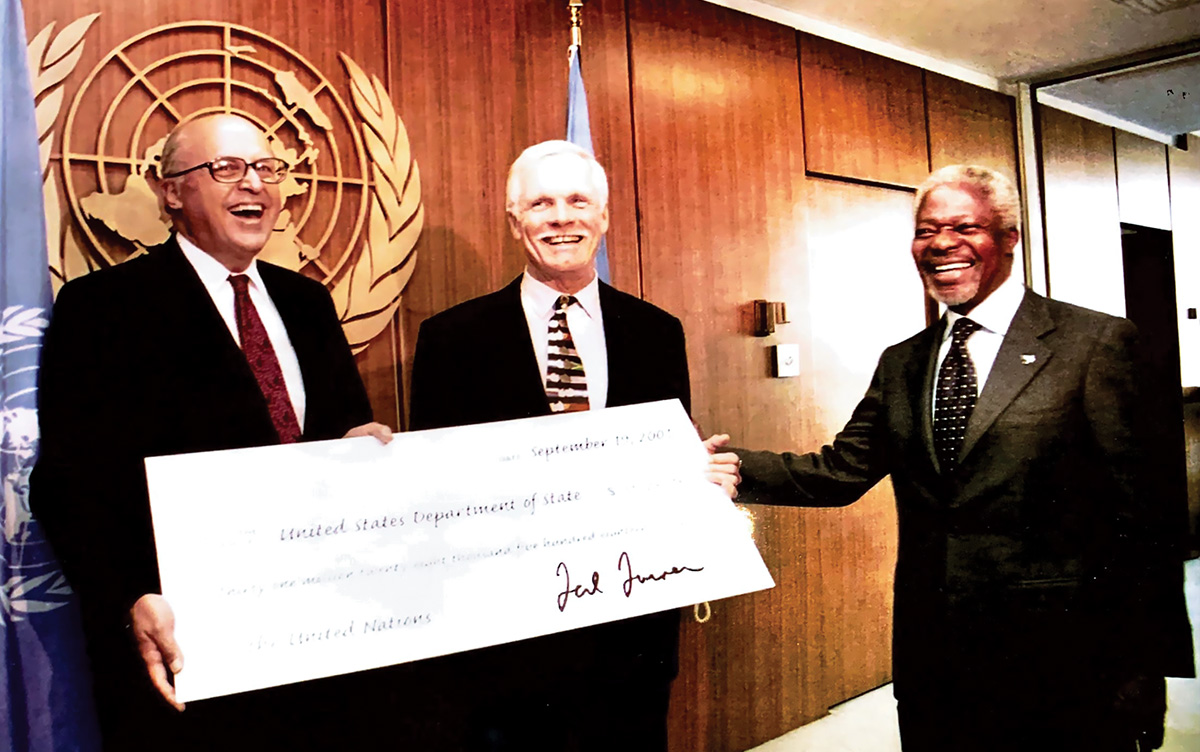

Then–U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. John Negroponte (at left) accepting a $31 million donation to the State Department from Ted Turner (center) for the United Nations in 2001. U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan is at right.

Courtesy of John D. Negroponte

Challenges and Accomplishments

FSJ: After “retiring” from the Foreign Service, you were given some of the most challenging diplomatic positions, including as U.S. Permanent Representative to the United Nations (2001-2004) as the U.S. reacted to 9/11 and the global war on terror ramped up with wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. What was working at the U.N. at that time like? Do you think America’s standing in international organizations has changed since then, and if so, how?

JDN: I loved working at USUN. It was a very intense time, and the U.N. Security Council was in full swing. I would say, initially at least, the atmosphere at the council was one of consensus about how to deal with international terrorism. We worked well with the Russians. The Chinese were low key, and the French and British worked very closely with us. We passed a seminal resolution (1441) on Iraq WMD inspections toward the end of 2002; but the consensus then frayed when we sought a resolution authorizing the use of force against Iraq in early 2003, which we ultimately had to withdraw because France threatened a veto.

Consensus took a blow, but I believe it was restored pretty quickly as we worked closely with the council on the occupation of Iraq and developed a political road map for the future.

Sometimes I feel we exaggerate the differences at the U.N. We are still the largest donor, and we are by and large supportive of peacekeeping, humanitarian programs and most of the other good things the U.N. does. I think there is more unity at the U.N. than sometimes meets the eye.

Negroponte, then U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, with Secretary of State Colin Powell outside the Security Council chamber at the U.N. in New York City, 2003.

Zaid Zaid / Courtesy of John D. Negroponte

FSJ: What are some of the lessons from the war in Iraq? What effective role can U.S. diplomats play in conflict zones? How can the Foreign Service better prepare for working with the military, working in war zones?

JDN: The biggest lesson for me was that we should have given UNSC Resolution 1441 and the WMD inspection regime more time to take effect. I was really surprised, even shocked by how quickly the Bush administration wanted to declare Iraq in further “material breach” of its UNSC obligations and go for a second resolution authorizing the use of force. I would have thought they might have waited six months or a year from the passage of 1441. But, no, they wanted to move almost immediately.

As for the war itself, I certainly felt we had good military-civilian cooperation, and we reached a good division of labor. Our FSOs stood up well to their responsibilities, both at the embassy and in branch offices, as well as on the provincial reconstruction teams. We had no difficulty recruiting FSO volunteers for service in Iraq, and I will always be proud of that.

As for preparing for future work in war zones, or with the military in general, I don’t think there is any set formula. Incentives are important. We made sure people who volunteered for service in Iraq were suitably rewarded in their subsequent assignment. And I think it helps to have a certain quotient of military veterans in the Foreign Service. But, frankly, each of these wars has had certain unique characteristics and circumstances, and those, too, help shape the civilian-military effort.

FSJ: You were the very first U.S. Director of National Intelligence after the position was created in 2005 in the wake of 9/11 to lead the intelligence community (IC). What were some of the challenges you faced, and what are you proudest of accomplishing as DNI?

JDN: The DNI was like a start-up. In some respects, we stood it up from scratch. I thought we strengthened communitywide capabilities. We increased open-source collection and analysis. And we brought the law enforcement community into closer partnership with the traditional foreign intelligence agencies. We especially strengthened the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), which was very important at the time. I think the DNI has played a positive role as manager of the IC. And for me personally, it was an honor and pleasure to participate in the president’s daily intelligence briefings. President Bush was, as they say in the IC, a good customer!

FSJ: What were some of the challenges you faced as Deputy Secretary of State, and what are you proudest of accomplishing as D?

JDN: Being Deputy Secretary is an all-consuming job. There was no second deputy, as there is now. So I worked on both the diplomatic and management issues. I had a “portfolio” of issues, if you will, that I worked on. The U.S.-China Strategic Political Dialogue, for example, was extremely interesting. I also dealt with Pakistan, plus various problems in Asia, the Middle East and Latin America.

On management, I was fortunate to have as a colleague Ambassador Patrick Kennedy, who always succeeded in making many of these issues seem easier than they were. We ramped up Foreign Service recruitment to a high pitch. We continued to staff the ongoing efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

We tried once again, unsuccessfully, to get the Law of the Sea Treaty (UNCLOS) ratified by the Senate. I was the lead State Department witness, along with the Deputy Secretary of Defense and the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It is an effort near and dear to my heart and high on my list of the department’s unfinished business.

Drawing on my extensive network of friends throughout the Bush administration, I think I succeeded in consolidating very good relations with the key Cabinet departments. My counterpart at Treasury, Bob Kimmitt, and I successfully revived the Treasury Attaché Program, which had been allowed to atrophy during the Clinton administration. And Gordon England over at Defense and I succeeded in making our bilateral monthly meetings something much more action-oriented, so much so that assistant secretaries were eagerly seeking to join us.

But the bread and butter of the job was, quite simply, running the department and getting done whatever the Secretary needed done, and there was a steady stream of challenges every single day.

Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte speaks to State Department employees in January 2008. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice is at left; at Amb. Negroponte’s right is his wife, Diana Villiers Negroponte.

U.S. Department of State

The Foreign Service Career

FSJ: When did you join AFSA? In your view what should AFSA’s top priorities be? Where can AFSA add the most value?

JDN: I joined AFSA early in my career. Then, at some point, I allowed my membership to lapse. I rejoined in 2007, when I became Deputy Secretary.

AFSA’s priorities are dictated by its mandate to advance the interests of the Foreign Service. I think it should focus on the importance of the career Service and minimization of political appointments. It would also do well to think about ways of fostering greater cooperation and unity among foreign affairs agencies.

Restoring the Treasury Attaché Program, Deputy Secretary of State John D. Negroponte with Deputy Treasurer Bob Kimmitt in the State Department Treaty Room, 2008.

U.S. Department of State

FSJ: What are the essential ingredients for a successful diplomat?

JDN: Experience.

FSJ: Is the Foreign Service as an institution stronger today? Has the role of the Foreign Service changed? What are the most critical reforms needed?

JDN: I think the Service is stronger as a collection of individuals than as an institution, overall. We would benefit from having more current active-duty FSOs in very senior positions both here and abroad.

FSJ: What areas, either functional or regional, would you point to that may require increased focus for American diplomacy in the coming years?

JDN: Language and area studies remain critically important, especially the study of China and Russia. The study of economics, including sustainability, is critical. But, above all, we must maintain a versatile and diverse workforce, capable of dealing with unexpected challenges.

FSJ: Since retiring from government, you have found time to do a lot of teaching. What is your message to students about the U.S. Foreign Service and government service more generally?

JDN: My message to students is that government service is a noble calling, and that a Foreign Service career is definitely worth pursuing. I have had Rangel and Pickering Fellows as my teaching assistants at Yale, George Washington and now Georgetown. I have been following the careers of many of my students who joined the government since 2010. It is an impressive group, and we try to meet at least once a year. Most recently, I met virtually with about 60 of my former students. A couple of them are already in fairly senior positions. One early Pickering Fellow is on his fifth Foreign Service assignment. This is inspiring.

My advice to students and recent graduates today is that, if they are interested in foreign affairs, they should seriously consider a Foreign Service career or some other foreign affairs opportunity, like working for a U.N. humanitarian agency or an international nongovernmental organization. There are numerous ways to serve in some sort of international capacity.

As for those who may be considering leaving the Service, my thought is this: Be careful what you wish for. You may quickly find that you are nostalgic for the work you were doing, and the cost of being “out of the arena” outweighs any benefit you may have expected from leaving the Service. I retired from the Foreign Service in 1997; but I assure you that one of the happiest days of my life was when I was called back to government. And I then stayed in as long as I possibly could.

John and Diana Negroponte with children, daughter-in-law, son-in-law and grandchildren.

Courtesy of John D. Negroponte