Deepening Working Relationships in Africa

The energy sector, broadly defined, offers enormous scope for investment and economic development as U.S. constructive engagement in Africa deepens. As always, however, the proof will be in the pudding.

BY HERMAN J. COHEN

The KivuWatt power project in Rwanda is unusual and important ecologically.

Contour Global

The second U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit took place in Washington, D.C., in December 2022 after nearly a decade. The Biden administration’s policy statement emphasized human rights, good governance, food security, peace, and a favorable environment for private sector investments. The summit’s focus was on extending and deepening the partnership between the U.S. and Africa.

The first summit, hosted by President Barack Obama in 2014 and themed “Investing in the Next Generation,” had focused on trade and investment in Africa and highlighted America’s commitment to Africa’s security, its democratic development, and its people. Representing the U.S. Corporate Council on Africa there, I attended the session in which African leaders met with representatives of the American business community and have a vivid memory of President Obama scolding the Africans with statements like, “You must get rid of corruption.”

Yet despite the tough rhetoric, in the following years U.S.-Africa relations continued much as before, with annual foreign aid budgets around $7 billion. Although the African Growth and Opportunity Act, which had been enacted in the year 2000, continued to give African countries duty-free entry for their manufactured products, only the Republics of South Africa and Senegal and the Kingdom of Lesotho have been able to take advantage of it. At the same time, however, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) established in 2004 and USAID’s Power Africa initiative established in 2013 have made steady progress in constructively engaging with Africa.

This second summit—in mobilizing officials, businesspeople, and civil society to address a wide range of old and new topics, in emphasizing “partnership” at every level, in increasing development assistance, and in cementing deals—appears to have qualitatively advanced the working relationship. As always, the proof will be in the pudding.

Energy and the Environment Prospects

The second day’s U.S.-Africa Business Forum, hosted by the Commerce Department, emphasized matchmaking. A “Deal Room” was set up to foster agreements between U.S. and African business representatives. Significantly, President Biden announced more than $15 billion in new two-way trade and investment commitments, deals, and partnerships at the forum. There were sessions on climate adaptation, health cooperation, a just energy transition, and cooperation in civil and commercial space research. And new agreements were reached that give momentum to energy and agricultural projects.

President Biden and President Felix Tshisekedi of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have agreed, for example, on preserving the rain forest of the Congo Basin. In addition to the DRC, the Congo Basin includes Equatorial Guinea, Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, and Angola. This forest is the second-largest CO2-absorbing “lung” in the world, after the Amazon. Until mid-2022, Chinese loggers in the Congo forest were shipping wood to China, and Congolese farmers were cutting trees to make room for agriculture required by population increase. Now tree cutting has stopped while U.S. and Congolese experts work to develop a system of conservation within limited commercial operations.

The energy sector, broadly defined, offers enormous scope for investment and economic development. Most African households continue to prepare meals with charcoal, which contributes to the cutting of rainforests. A major effort is underway to expand the use of gas, which produces far less CO2 than coal, for the preparation of meals. Gas canisters for meal preparation are currently the rule in South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia.

Since the year 2010, significant gas deposits have been discovered near offshore in both West and East Africa. The deposits are measured upward of 40 trillion cubic feet in each region. They are currently being developed to produce liquid natural gas (LNG) that will replace dirty coal for the generation of electricity. In northern Mozambique, in the province of Cabo Delgado, offshore gas is processed into LNG, which will be used by private companies to generate electricity. A U.S. company, Anglo Eurasia of Houston, Texas, has received a permit from the Mozambican government to invest in a power plant in the province to produce electricity from LNG derived from offshore gas. This power will be sold to southern Malawi, Zambia, and South Africa, all of whom had serious power deficits as of the end of 2022.

Power Africa, a USAID program promoting private investments in power generation in sub-Saharan Africa that will amount to 30,000 megawatts (MW) by 2030, has become another major facilitator for economic development partnerships. I have personally worked on negotiations to create five new power plants in Africa for the company Contour Global. Three of these plants are in Nigeria; one is in Togo and one in Rwanda.

The power plant in Rwanda is particularly interesting. It utilizes gas that is in suspension in Lake Kivu as fuel. The gas seeps up from the lake bottom. The company pipes the gas from a floating barge to the power plant on shore. Besides supplying power, the plant is of critical importance ecologically. If the gas is not extracted from the lake, the gas buildup will cause a major explosion at some point during the next hundred years. Such an explosion happened in 1986 in Lake Nyos in northwest Cameroon, killing 1,746 people and 3,500 livestock.

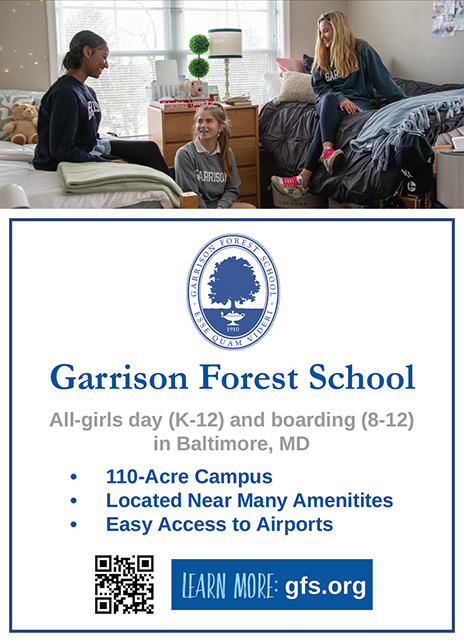

Map showing the beneficially affected countries.

Stekruebe / Wikimedia

Renewables and Food Security

Improvements in operations and infrastructure at Benin’s Port of Cotonou supported by the Millennium Challenge Corporation are opening up the economic potential of the region.

Stekruebe / Wikimedia

There is also significant potential for renewable energy in Africa. Of particular significance is the Grand Inga hydroelectric complex on the Congo River, approximately 50 miles from the Atlantic Ocean port of Boma. The complex now consists of two power plants—Inga 1 and Inga 2, completed in 1972 and 1982, respectively—and is currently producing 1,100 MW, with 500 MW flowing to the Southern African Power Pool switch in Zambia. The DC transmission line was financed in 1992 with a loan from Bankers Trust guaranteed by the U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corporation.

The complete Grand Inga project envisions adding six more power plants to the complex, bringing total capacity to more than 40,000 MW and making it the world’s largest hydroelectric project. The second phase involves construction of a third plant, Inga 3, which is slated to increase power output by about 4,000 MW. All the inhabitants of the district where the Inga 3 plant is sited were relocated in the year 2000. As of 2022, the planning for construction of the third plant was being done by Spanish private contractors.

Though the overall Grand Inga project was discussed at the summit, there appears to be no prospect for financing the third and last phase in the foreseeable future. The second phase, construction of Inga 3, however, was of particular interest because it would make electricity available to the entire central African subregion. The USAID office Power Africa is available to facilitate potential American power company investments.

Other sources of renewable energy are wind and solar, both abundant in different Africa subregions. Because wind does not blow all the time, and because the sun does not shine at night, batteries are required for energy storage. Storage batteries require the minerals cobalt and lithium, both of which are abundant in Africa. As of 2022, lithium mines were under development in Zimbabwe, Namibia, Ghana, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Mali. The DRC has the second-largest known deposit of cobalt after Russia. In general, Africa is potentially very strong in renewables—provided the necessary financing becomes available.

The last day of the summit, devoted to leaders sessions, closed with a discussion on partnering to promote food security and food systems resilience. Food security in Africa is precarious because so much of the food Africans consume originates abroad, where unexpected events occasionally cause supply interruptions. A good example is the Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022. In normal times, Ukraine supplies 40 percent of the wheat that Africa uses to make bread. During the first three months of 2022, Russia was able to prevent Ukrainian ships from transiting the Crimea straits, thereby cutting Africa off from its major source of wheat. After the international media cast blame on Russia, grain shipments were resumed under an agreement brokered by the United Nations and Türkiye for safe Black Sea export of Ukrainian grain.

After international food shipments arrive in African ports, however, there are often problems with storage and road transportation. The Republic of Madagascar, an island, is noteworthy for its food storage and transportation issues. Many other African nations suffer from the same logistical problems.

Millennium Challenge Corporation CEO Alice Albright, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken (top center), President of Benin Patrice Talon (top left), and President of Niger Mohamed Bazoum (top right) sign documents during the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, D.C., on Dec. 14, 2022.

Scott Taetsch / U.S. Department of State

Moving Toward Partnerships

In several public statements, President Biden has stressed that respect for human rights and democracy are at the core of his foreign policy. These issues play a role in Africa mainly in implementation of the programs of the Millennium Challenge Corporation, established with strong bipartisan backing during the administration of President George W. Bush. The MCC judges the eligibility of countries against a list of established criteria decided by independent nongovernmental organizations, including respect for human rights and democracy.

The issues of democracy and good governance are possibly the most difficult to evaluate. The American government democracy institutes, the National Democratic Institute and the International Republican Institute, have determined that two consecutive transparent, free, and fair elections, as witnessed by impartial observers, qualify a government as democratic. The African governments that have achieved the designation “democracy” are the same as those that have qualified for Millennium Challenge Corporation compacts.

In the first year of the program, eight African countries were declared eligible. Compacts were negotiated that determined how the recipient countries would use large sums of money. The West African Republic of Benin was one of the first countries to sign a compact with the MCC, in 2006. The five-year, $307 million compact with the Government of Benin aimed to increase investments and private sector activity through the implementation of four projects: (1) increase access to land through more secure and useful land tenure; (2) expand access to financial services through grants given to micro, small, and medium enterprises; (3) provide access to justice by bringing courts closer to rural populations; and (4) improve access to markets by eliminating physical and procedural constraints currently hindering the flow of goods through the Port of Cotonou.

Successful elimination of constraints hindering the flow of goods through the Port of Cotonou has been, in my view, the most effective part of the Benin compact. Because of the port’s increased efficiency, especially the elimination of long waiting time in the port, the West African private sector has shifted much of its cargos to Benin. At the December summit, the MCC announced Benin’s first regional compact, with Niger, a $504 million grant to improve the trade corridor between Cotonou and Niger’s capital city, Niamey.

Other African countries that have signed compacts with the MCC include Cabo Verde, Ghana, Lesotho, Mali, Morocco, and Mozambique. MCC investments in Mozambique fisheries have made that country a major exporter of fish products, including a weekly lobster/shrimp flight to nourish the restaurants of New York.

U.S.-Africa relations are also active in the military sector. The Africa Center for Strategic Studies, situated in the National Defense University, had a special meeting of African military leaders during the summit designed to enhance professionalism within the African militaries.

Finally, the Development Finance Corporation, formerly the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, is giving guarantees to American companies investing in Africa. Including guarantees against expropriation and natural disasters, this initiative is a substantial incentive for private sector investment.

Did the 2022 U.S.-Africa summit make a difference in U.S.-Africa relations? On the American side, the word “partnership” served as the key to the American vision. The signal sent to the Africans by that word was that the U.S. will no longer view Africa as a charity case. U.S. funding must be matched by African political and economic reforms, honestly implemented, that justify the American taxpayers’ efforts.

Now for the hard part.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “FS Institution Builder and Africa Hand” conversation with Ambassador Hank Cohen, The Foreign Service Journal, December 2019

- “Waging Peace in Africa” by Herman J. Cohen, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2000

- “Energy Diplomacy Works: How Power Africa Redefines Development Partnerships” by Andrew M. Herscowitz, The Foreign Service Journal, March 2020