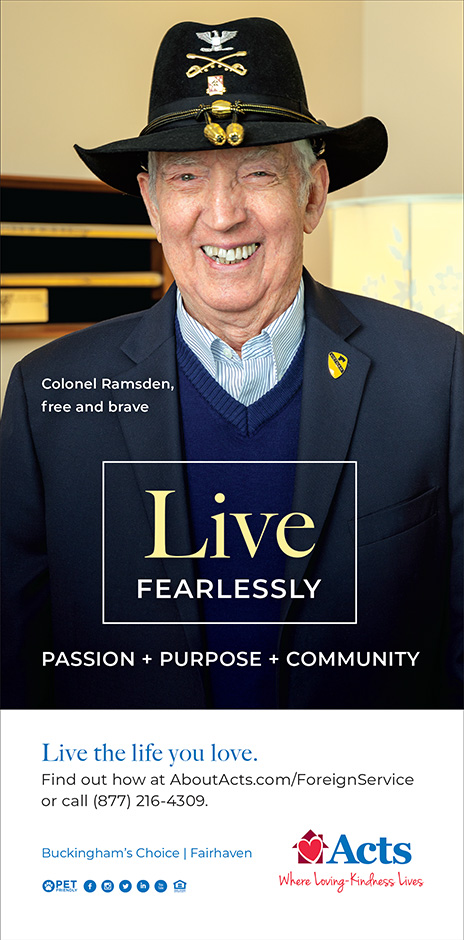

Dogging It in the Foreign Service

Reflections

BY DAVE DUNFORD

Pichi on Pichincha above Quito.

Courtesy of Dave Dunford

I’ve found being part of a Foreign Service family makes us at times strangers in a strange land. Dogs, for many of us, are integral members of the family. I believe that overcoming the challenges of shipping them to and from exotic places and finding reliable veterinarians were things I signed up for when I joined. I hope that governments and airlines will allow pets to continue to enrich the lives of those who choose a Foreign Service career. Here are a few who enriched mine.

Pichi

We got our golden retriever puppy, Pichi, from a breeder in Virginia where we were living during my time in the A-100 course and Spanish language training. We knew when we got him that we were assigned to Quito. He was named after the mountain overlooking the capital city.

We left for Ecuador on December 31, 1966, and arrived 10 days later. Thanks to the shipping lobby’s clout, my wife, Sandy, and I sailed on Grace Line’s Santa Magdalena. Pichi traveled in a small compartment on the top deck. After nearly two years hiking in the Andes, Pichi flew back with us to Washington where I was transferred for Finnish language training at the Foreign Service Institute. Soon, he would be a trilingual dog, responding to commands in English, Spanish—and Finnish.

For my next assignment, in Finland, Pichi arrived in Helsinki by air but only after running amok at JFK for several hours and missing his scheduled flight. The Finnish vet at the airport kindly waived the quarantine requirement and paroled him to our custody. Pichi adapted to apartment living in the Helsinki suburb of Tapiola and the arrival of two rugrats named Greg and Tina. Sadly, his heart stopped on a Finnish veterinarian’s table during a routine procedure.

Doc and Jack

Back in the U.S., another golden retriever puppy came into our lives. As our time in Washington, D.C., extended to nine years, Doc was getting comfortable in his golden years when two cataclysmic events occurred: A yellow Labrador retriever pup named Jack arrived, and we all moved to Cairo.

Doc was good natured, lovable, and reasonably well behaved. Jack was far more intense, passionate about food and frisbees. Neighborhood kids would gather to watch him inhale his dinner. One day he got into a major cache of freeze-dried food bought for a backpacking trip. He then drank water and swelled up like the rat Templeton from Charlotte’s Web. Jack advanced to the Virginia state finals in a dog frisbee event, and all agreed that he was national championship material if only his thrower (me) had been more competent.

The move to Egypt marked the end of Jack’s promising frisbee career. The dogs were on our flight to Cairo, in the cargo hold. When Doc and Jack led us out of airport security, the packed crowd parted as I imagined the Red Sea did for Moses. The dogs lived comfortably in Ma’adi, a southern suburb of Cairo, thanks to a generous yard, a household staff, and a gardener. Finding a vet in Cairo was always a challenge.

After three years in Egypt, I flew back to JFK with Doc and Jack in the hold. Sandy and the kids, who preceded me, met me as I retrieved my luggage and waited for the dogs. Eventually cages came up on an elevator. A customs official yelled, “Don’t come near us. Take the dogs and go.” Doc, now 12, had not traveled well, and the stench was unmistakable. We loaded the stinky dogs in the car and fled, leaving the cages behind. When we were confident that sirens and flashing lights weren’t following us, we pulled into a gas station and did our best to clean up the dogs.

Moose and Jack in Riyadh.

Courtesy of Dave Dunford

Jack and Moose

Jack playing frisbee in Cairo.

Courtesy of Dave Dunford

Four years later, it was time to transport two dogs to Saudi Arabia. Doc had died peacefully in Virginia at age 13. Moose, a black Lab, was Jack’s new companion. Only guard dogs and seeing-eye dogs could enter Saudi Arabia. No worries. Declaring the two Labs as guard dogs was not a huge stretch. The paperwork was more daunting.

First, we needed health certificates from our vet in Fairfax. Then the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Annapolis had to certify that our vet was properly licensed. I took the certificates to a small office at State and took a number. After an hour, the woman behind the counter presented me with a formal document and unabashedly signed it George C. Shultz (then Secretary of State). At the Saudi embassy, an employee stamped the back of the Shultz document with an attestation in Arabic, tied the three documents together with a ribbon, and added an impressive seal. Jack and Moose now could begin their assignments as guard dogs in Riyadh.

Saudi Arabia is not ideal for two energetic Labrador retrievers, but the deputy chief of mission’s residence, our home, was always filled with people, and dog walks in Riyadh’s diplomatic quarter included splashing through the many fountains. Moose launched us on an adventure by swallowing a racquet ball. We drove him four hours to Aramco in Dhahran for the surgery and then returned to get him after he recovered.

Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait turned Riyadh into the center of the world for several months and, arguably, contributed to my nomination as ambassador to Oman. In what seemed sensible at the time, we boarded the dogs at the Aramco kennel in Dhahran.

More than five months later, we were reunited with the dogs at the consul general’s residence in Dhahran. Moose seemed fine, but age and lack of exercise had weakened Jack. Dog ownership in Oman, given British influence, was relatively common. Oman did, however, require dogs to have photo IDs. After 30 minutes of bedlam in a photographer’s studio, punctuated by snarls and yelps and curses, we walked out with acceptable photographs.

A Glimpse of Dog Heaven

When we returned from a U.S. trip, Jack was struggling. I took him for his last car ride to a British vet who diagnosed the problem as mouth cancer. I reluctantly agreed to put him down. That same morning, I had a difficult meeting with Haitham bin Tariq, then deputy foreign minister and now sultan, on the cancellation of our economic assistance program. I had lost a good friend, and I struggled to manage this delicate meeting.

Our residence in Oman had overlooked an Indian Ocean beach. When we took the dogs there, Jack would plod along the surf, happy to get wet but careful to avoid swimming. Moose, on the other hand, would race in and out of the waves chasing tennis balls and scattering gulls. Now, sitting on our balcony, we imagined Jack with his tennis ball slowly walking behind Moose along the beach.

Then one day, a yellow Lab raced across the sand with the blinding speed of the youthful Jack. Another yellow Lab followed, splashing happily through the waves. Looking at the unspoiled beach and the sun setting over the Indian Ocean, we were looking at dog heaven.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.