Extending the American Revolution Overseas: Foreign Aid, 1789–1850

Foreign assistance is part of America’s cultural DNA, fostered by the country’s revolutionary heritage of a commitment to human rights and individual liberties.

BY JOHN SANBRAILO

Benjamin Franklin (at left), John Adams and Thomas Jefferson (standing) review a draft of the Declaration of Independence.

Jean Leon Gerome Ferris / Library of Congress

Modern analyses of U.S. foreign assistance typically describe it as a post-World War II innovation that began with the Marshall Plan and President Harry Truman’s Point Four aid program in the late 1940s. Following the lead of international relations theorist Hans Morgenthau, many practitioners believe that foreign aid arose as an instrument of Cold War diplomacy, and that aid as we know it might not now exist without the Cold War.

This article presents an alternative view, expanding on an article by Glenn Rogers, “A Long-Term Perspective on U.S. Foreign Development Cooperation” (May 2010 FSJ). Foreign aid is deeply rooted in American history, and has evolved over more than 200 years to improve the lives of hundreds of millions of people throughout the globe while also supporting vital U.S. interests.

Foreign assistance reflects what historian Gordon Wood identifies in his book The Idea of America: Reflections on the Birth of the United States (Penguin, 2011) as a fundamental element of the country’s revolutionary tradition: the desire to spread democracy and development overseas. It is part of the country’s cultural DNA, fostered by its unique revolutionary heritage of a commitment to human rights and individual liberties. Aid expresses the nation’s sense of a universal mission to nurture freedom and prosperity in other countries, a mission that has regularly been an integral part of U.S. foreign policy purposes.

The desire to share the principles of the American Revolution with other countries was driven not only by diplomats and government officials, but by missionaries, traders, educators, scientists, agriculturalists, academics, progressive reformers, civil society groups, business leaders and the military. These early undertakings were similar to aid programs in recent decades, offering useful comparisons.

Jefferson’s belief that “this ball of liberty will roll round the world” was reflected in his proposals to spread “republican principles” to Russia, Poland, Greece and the emerging South American nations.

Earliest Initiatives

The Founding Fathers were, above all, what we might call “development philosophers.” The writings of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton explore how societies move toward greater liberty and progress. Franklin’s Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind and Peopling of Countries, etc., published in 1751, outlined one of the first comprehensive development theories. In it, he describes how the interests of rich countries are enhanced by promoting progress in their poorer territories. These ideas have endured to this day as a central pillar of foreign aid policy.

Works such as Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack and Autobiography, Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia and Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures embody fundamental principles that have shaped U.S. approaches to the world for more than two centuries. They are often incorporated in modern foreign assistance legislation without anyone ever realizing their origins. The founders established institutions to advance liberty, equality, representative government and the pursuit of happiness that continue to influence how Americans view international development and their role in the world.

John J. Crittenden (1787-1863) was the 17th governor of Kentucky and served twice as U.S. Attorney General. He represented the state in the U.S. Congress and strongly supported an “Appeal to the People of the Nation” to contribute to the relief effort following the Great Potato Famine in Ireland.

Library of Congress, Taken by Mathew Brady

One of the earliest examples of American promotion of democracy overseas was the collaboration in Paris between Jefferson and General Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, in drafting the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” in 1789. This historic document marked the beginnings of the French Revolution and was greatly influenced by the Virginia Declaration of Rights and the American Declaration of Independence. Jefferson’s belief that “this ball of liberty will roll round the world” was reflected in his proposals to spread “republican principles” to Russia, Poland, Greece and the emerging Latin American nations. In more recent years, they are seen in U.S. support for the Arab Spring and democratic transitions throughout the world.

From his first encounters with Native Americans in what were then sovereign nations in the western region of North America, Jefferson advised: “We desire above all things, brother, to instruct you in whatever we know ourselves. We wish you to learn all our arts and to make you wise and wealthy.” He instructed his secretary, Meriwether Lewis, to arrange smallpox vaccinations for Indian tribes along the route of the Lewis and Clark expedition, expressing attitudes toward traditional people that would evolve into foreign assistance over the decades to come.

Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton supported aid to Saint Domingue (now Haiti) to address the consequences of the struggle for independence of that Caribbean island. Thousands of refugees fled to the United States in 1792 and 1793. Their plight led the U.S. Congress to establish a relief fund, thereby setting one of the earliest precedents for aid to foreign citizens. Today the State Department’s Bureau for Population, Refugees and Migration carries out similar initiatives to ease the suffering of uprooted people around the world and integrate humanitarian principles into U.S. foreign policy.

From 1798 to 1801, President John Adams and Haitian leader Toussaint L’Ouverture forged diplomatic ties that allowed Americans to support the creation of the world’s first Black Republic. As detailed in Diplomacy in Black and White (University of Georgia Press, 2014), the United States provided the revolutionaries with economic assistance, arms and naval backing. As the highest-ranking U.S. diplomat dispatched to Saint Domingue, Dr. Edward Stevens played a crucial role in advising L’Ouverture and mobilizing aid from the Adams administration. This cooperation was of great strategic importance in bringing forth the new nation of Haiti, upholding American democratic ideals and slowly altering the Atlantic region’s discourse on slavery and race. It also opened markets for U.S. trade and undermined French interests, leading to the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

Seeds planted around the world by the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the Constitution and its Bill of Rights would slowly grow throughout the 19th century. Numerous Americans conspired with Latin American rebels in their plans to liberate South America as a means of developing the continent and expanding commercial opportunities. Foreign writers pointed to Benjamin Franklin and George Washington as models for promoting economic progress and democratic leadership. They regularly cited Franklin’s declaration that America’s cause “is the cause of all mankind.”

Extending the American Revolution Overseas

Even during the initial decades of the 19th century, when U.S. attention focused largely on continental expansion and consolidation of the federal system of government, foreign technical assistance that is similar to what we know today was undertaken. For example, one of the wealthiest, most cosmopolitan figures of the period, Joel Poinsett from Charleston, South Carolina, traveled to Russia in 1806 and 1807, advising Czar Alexander I on economic and agricultural improvements, assessing that country’s natural resources and advocating freedom for the serfs. In 1811, President James Madison called for an “enlarged philanthropy” in dealing with the revolutionary events “developing themselves among the great communities which occupy the southern portion of our hemisphere and extending into our own neighborhood.”

Joel R. Poinsett (1779-1851) was Secretary of War and America’s first diplomat to serve in Chile.

As the first U.S. diplomat to serve in Chile (1810-1814), Poinsett helped that country prepare its constitution and develop plans for its national government. He conducted training courses on the Bill of Rights and promoted agricultural production, while leading local troops fighting for Chile’s independence from Spain. As minister to Mexico (1825-1829), Poinsett used Masonic lodges to build greater awareness of democratic practices and governance, activity comparable to civil society development programs supported today by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the National Endowment for Democracy. Admittedly, Poinsett exceeded his instructions to promote U.S. goodwill and trade relations which demonstrates the tension between the idealist and realist approaches to American foreign policy that continues to this day.

Other Americans traveled to South America to aid its wars of independence, encourage trade and render humanitarian assistance, often remaining there afterward to advance national progress. In 1812, Congress appropriated $50,000 to ship flour to earthquake victims in Venezuela. The flour was delivered by diplomat Alexander Scott, who was instructed to highlight that this aid was “strong proof of the friendship and interest which the United States…has in their welfare…and to explain the mutual advantages of commerce with the United States.”

In 1819, at the request of President James Monroe, Congress appropriated funds for an even more ambitious overseas nation-building effort, providing $100,000 to the American Colonization Society for settlement of freed blacks to Liberia. Historian Daniel Walker Howe considers this “one of the most grandiose schemes of social engineering ever entertained in the United States.” Led by Bushrod Washington, the nephew of President George Washington and a Supreme Court justice, and other prominent figures like Henry Clay, the ACS obtained funds from private donors and later from the Virginia legislature and other states to establish Liberia, which led to its independence in 1847 and to Africa’s first democratic republic.

Liberia and Haiti were unique in the 19th century, and U.S. assistance played a crucial role in helping to create both countries. Although both were largely ignored in subsequent policies, these republics contributed to weakening the institution of slavery and slowly changing the debate on race relations by demonstrating that blacks were capable of self-government, setting the stage for 20th-century African independence movements. Such examples illustrate that foreign assistance can often have unintended outcomes.

The first nongovernmental organizations to work overseas were incorporated in the 1810s, spurred in part by the patriotic fervor that followed the War of 1812. Among them was the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, the aforementioned ACS and the American Bible Society, all three early precedents for private actions to transfer democratic ideals and new knowledge to other lands. While their primary aims were evangelizing and promoting Bible studies, they also encouraged democratic values, education reforms, community development and health projects. Peter Parker in China, Isaac Wheelwright in Ecuador and Charles Jefferson Harrah in Brazil all carried out such activities. To cite just one example: in the 1830s and 1840s, Parker introduced Western medicine into China, trained hundreds of doctors and developed the Medical Missionary Society of China—while also serving as chargé d’affaires of the U.S. legation and facilitating treaty negotiations with the Qing Dynasty.

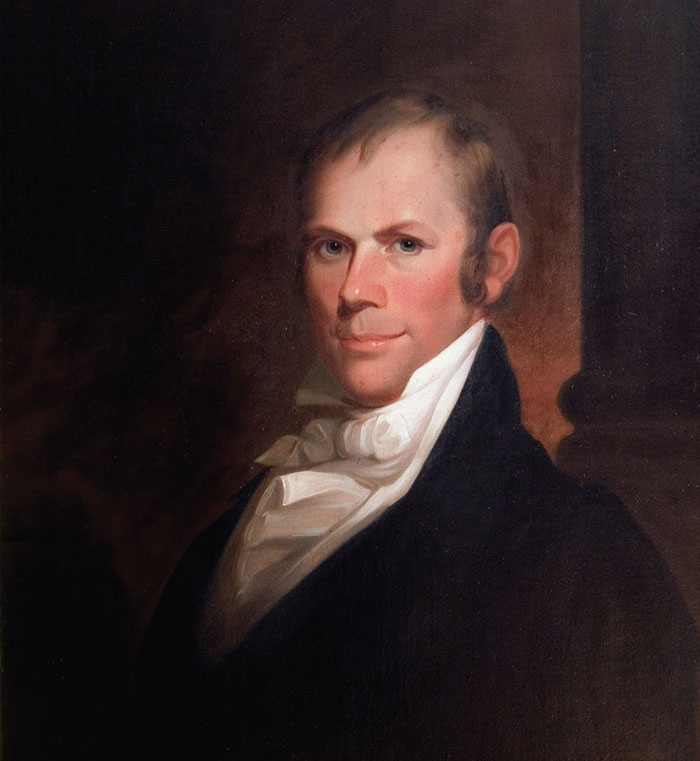

Henry Clay (1777-1852) was renowned in the Western Hemisphere as a strong proponent of pan-Americanism.

Transylvania University Matthew Harris Jouett.

Some of the first translations into Spanish of the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights entered Latin America thanks to New England merchants and missionaries, through instruction they provided on democratic practices. Together with local leaders, they translated the Federalist Papers and the Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin into Spanish to use in newly established public schools. These teachers were not unlike today’s Peace Corps Volunteers, symbolizing the strong spirit of solidarity and shared humanity that has influenced foreign assistance from its inception.

A Pan-American Vision

In the 1820s, Representative Henry Clay became one of the most ardent champions of United States cooperation with the newly emerging countries of South America. In his speeches advocating diplomatic recognition of these new nations, Clay proposed an “American System” of independent, democratic nations peacefully interconnected by trade and mutual cooperation, which he saw as important for national growth and prosperity. Historians see Clay as articulating the first comprehensive vision of international development that would later be seen in the creation of the Inter-American System, the Pan American Union, the Good Neighbor Policy, the Organization of American States, the Alliance for Progress and similar regional initiatives.

Most presentations of the period highlight the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, often discussing it as the birth of American imperialism. Clay’s positive vision of hemispheric integration and his proposal of a policy of “good neighborhood” are often overlooked or dismissed as self-serving moves to support his political ambitions. His statements on the “spiritual links and great destiny the two Americas could share by building together” are similarly positive, even though they were motivated, at least in part, by a desire to end Spanish trade restrictions and hasten U.S. expansion into Texas. While his plan for hemispheric cooperation is not well known, Clay is one of the very few among the pantheon of leaders of the Americas who is honored with a bust in the historic OAS headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Inspired by Clay’s pan-Americanism, William Wheelwright from Newburyport, Massachusetts, was the first U.S. diplomat in Guayaquil, Ecuador (1825-1829), importing the country’s first steam engine and helping develop local industries. He later became the leading steamship and railroad pioneer in South America, implementing the earliest regional integration projects. He launched steamship travel along the Pacific coast, introduced the telegraph, built a transcontinental railroad connecting Chile and Argentina in the 1850s, and initiated mining projects and community improvements.

Wheelwright’s brother Isaac was an education adviser in Ecuador and Chile, establishing the first public schools for girls there. These technical assistance and investment initiatives began a process of translating Clay’s vision into action and were forerunners of modern cooperation programs. William Wheelwright is unique among American diplomats and entrepreneurs in being honored by a statue in Valparaíso that was erected and paid for by contributions from the Chilean people.

A United Nations peacekeeper helps locals move American food aid in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

Creative Commons / U.S. Navy

Humanitarian Assistance & Technical Advice

Building on the precedents of aiding Haitian refugees and Venezuelan earthquake victims, individuals and the private sector contributed generously to alleviate the suffering caused by humanitarian crises, famines and natural disasters in other lands. During the 1820s, “Greek Fever” seized the American public, which mobilized to aid that country’s struggle for freedom from the Ottoman Turks. Citizens’ committees in principal U.S. cities, dubbed “hellenophiles” and led by figures like Edward Everett and Mathew Carey, raised funds to send food, supplies, volunteers and cash to the distressed Greek population. This assistance included agricultural tools and support for rebuilding homes and schools, not unlike similar modern responses for other causes.

No event in the first half of the 19th century led to such widespread American giving as the Great Potato Famine in Ireland. In American Philanthropy Abroad (Rutgers University Press, 1963), Merle Curti cites this relief effort as “the first truly national organized campaign for helping the distressed in foreign lands.” Even President James Polk made a personal contribution, although he did not favor federal aid. Other prominent Americans such as Vice President George Mifflin Dallas and Senator John J. Crittenden, and business leaders like Amos Lawrence, strongly supported an “Appeal to the People of the Nation” to contribute. In 1847-1848 alone, more than a million dollars was raised, including $800 from the Cherokee and Choctaw nations, to ship emergency food and other relief to Ireland. With great fanfare vessels regularly departed from major U.S. ports, with the government providing some naval shipping support—an early example of a public-private partnership.

The first nongovernmental organizations to work overseas were incorporated in the 1810s, spurred in part by the patriotic fervor that followed the War of 1812.

As noted in Kendall Birr and Merle Curti’s Prelude to Point Four: American Technical Missions Overseas (University of Wisconsin Press, 1954), the U.S. government began responding to a growing number of technical assistance requests from foreign countries starting in the 1830s. International visitors regularly traveled to the United States to observe the accomplishments of the self-taught engineers who constructed the Erie Canal and other infrastructure projects. The development of steamboats and railroads, and the newly invented telegraph (the Internet of its day), attracted increasing attention. By the late 1840s, Americans were already building railroads and telegraph lines in foreign lands, such as George Washington Whistler in Russia and the initiation of the Panama Railroad, an engineering marvel of the era. Rapidly increasing agricultural production and the machinery of Cyrus McCormick were generating frequent requests for agricultural experts.

In addition, foreigners viewed with great interest the American public school system and recruited advisers who could replicate it overseas. They traveled here to observe new ideas about penology, care for the insane and abused women, and creation of voluntary associations. Many were intrigued by the American experiment in representative democracy and wondered how it might be established elsewhere. By 1850, Minister George Bancroft was reporting from London that the U.S. had surpassed Britain in commerce, manufacturing and wealth. World leaders saw the U.S. as a growing center of discovery and as a provider of knowledge and techniques that would accelerate economic and social progress. Such initiatives would further expand after the Civil War.

History Matters

The USAID logo we know today bears a distinct resemblance to the Jefferson Peace Medal, as shown here. Peace and friendship medals minted in silver by the U.S. government were an aspect of diplomacy with Native Americans and others during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Jefferson Peace Medal / Oregon Historical Society

Modern aid programs are part of a tradition that dates back to the founding of the republic. During the six decades following independence, Americans advocated international engagement and wrote about how it would benefit the United States and other nations. They encouraged initiatives to share with the world the fruits of the American Revolution, although trade expansion and other national interests were also fundamental concerns. While many have forgotten Henry Clay’s proposal for Western Hemisphere collaboration, his vision lived on to inspire Secretary of State James G. Blaine to help create the Inter-American System in 1890. That led, in turn, to the establishment of the Pan-American Union, the first modern multilateral organization for regional cooperation and development and a model for the future League of Nations, United Nations and Organization of American States.

Indeed, many of the elements that we recognize as modern foreign aid emerged during this period: congressionally appropriated funds; humanitarian assistance and food shipments for victims of conflict, famine and natural disasters; support to revolutionary regimes and new nations; technical advice for improving education, medical care and agriculture; the establishment of NGOs operating overseas; the dispatch of volunteers to foreign lands; support for industrial and infrastructure development; public-private partnerships; and promotion of democracy and what we now call “nation-building.”

Such a perspective may help to explain how President George W. Bush could enter office opposed to overseas nation-building, yet subsequently embark on the most ambitious such efforts in American history in Iraq and Afghanistan while achieving the largest increase in foreign assistance since the Marshall Plan. Or why President Barack Obama, in his Second Inaugural Address in January 2013, echoed Thomas Jefferson in proclaiming: “We will support democracy from Asia to Africa; from the Americas to the Middle East; because our interests and our conscience compel us to act on behalf of those who long for freedom. We must be a source of hope to the poor, the sick, the marginalized, the victims of injustice. Our individual freedom is inextricably bound to the freedom of every soul on Earth.”

As Abraham Lincoln famously observed, “We cannot escape history.” Foreign assistance is not merely a temporary aberration or a response to immediate international crises. It has been a fundamental part of U.S. engagement with the world and defines who we are as a people. If Americans stopped trying to improve and democratize the world, they would stop being American.

Read More...

- Observations concerning the increase of mankind, peopling of countries, etc. by Benjamin Franklin (Archives.org)

- The American Colonization Society, 1816-1865 (Africans in America, PBS)

- ’The Cause of the Greeks’: Philadelphia and the Greek War for Independence, 1821-1828 by Angelo Repousis (Temple University, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, October 1999)