The Letter That Saved a Romanian Diplomat-Spy

Reflections

BY JONATHAN B. RICKERT

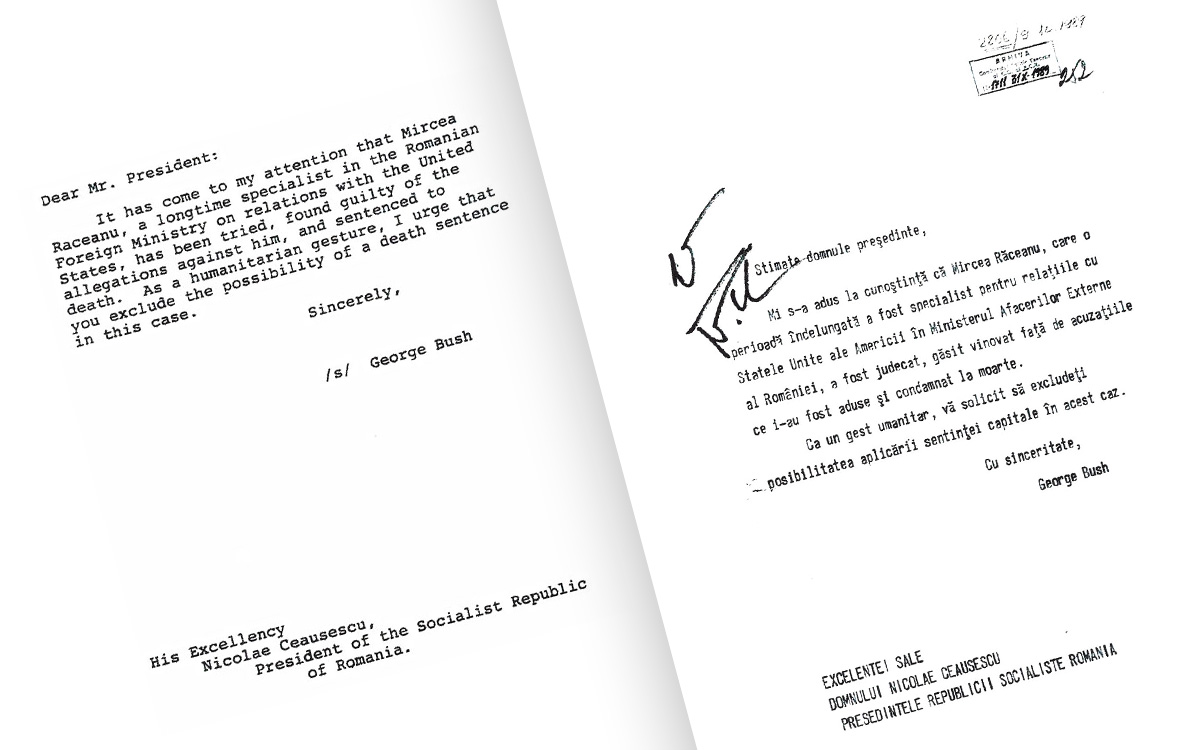

This pivotal letter, in the original English and as translated into Romanian (the Romanian-language copy bears a stamp from the archives of the Political Executive Committee of the Communist Party’s Central Committee), was included in the second edition of Mircea Raceanu’s book, published in 2009.

Courtesy of Jonathan Rickert

In 2001 Mircea was awarded the National Order for Merit by the Romanian government.

Wikipedia

I first met Romanian diplomat and expert on U.S. relations Mircea Raceanu sometime around 1982, while I was the State Department desk officer for Romania. With his extensive service in the United States and in the North America Division of the Foreign Ministry, Mircea was well known to many of us who had dealt with his country.

He and I got on well from the onset and have been friends ever since. What I never knew, however, until after his arrest in Bucharest by the Romanian authorities early in 1989, was that he had been providing information to the CIA for many years. In other words, in an attempt to bring democracy to Romania, he was spying against his own government, led by communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu.

After his arrest, Mircea was charged with treason, interrogated at length, tried by a military tribunal, found guilty, and sentenced to death. He has described this whole experience vividly in his Romanian-language book, Infern ’89: Povestea unui condemnat la moarte (Inferno ’89: The Story of One Condemned to Death), originally published in 2000.

One of the book’s most interesting parts explains how his death sentence was commuted to 20 years’ imprisonment. (Mircea was freed from prison in connection with the December 1989 revolution but was forced by the new Romanian authorities to leave the country—he settled in the United States with his family not long thereafter.) Here’s how it happened.

On Sept. 10, 1989, the U.S. chargé d’affaires ad interim in Bucharest, Larry Napper, met with President Ceausescu to deliver a short letter from President George H.W. Bush. Deputy Secretary Lawrence Eagleburger had prepared the way for the meeting by reaching out to Deputy Prime Minister Stefan Andrei for assistance in setting it up.

The letter urged Ceausescu to “exclude the possibility of applying the death sentence” in Raceanu’s case. It appeared to take the Romanian dictator completely by surprise—he may have been expecting a response to an earlier letter that he had sent to Bush and otherwise might not have deigned to meet with a “mere” chargé.

Though Ceausescu brusquely terminated his session with Napper as soon as he learned why he had come, the letter had the desired effect, since Mircea’s death sentence was commuted shortly thereafter.

Mircea himself knew nothing about how these events all had happened until after the revolution, when the interpreter at the Ceausescu-Napper meeting, Gheorghe Petricu, told him the story. Mircea described that meeting in his manuscript, based on what Petricu had related. Nevertheless, like a responsible journalist, he wanted to obtain corroboration of the incident, rather than relying on only one source. The only person present at the meeting other than Ceausescu and his interpreter was Larry Napper.

As it happened, I was working for Larry at the State Department immediately after my 1998 retirement. When Mircea learned of this connection, he asked if I would set up a meeting for him with Larry to discuss the matter of the letter. He gave me the relevant text from his draft, about three pages, which I translated into English. Larry readily agreed to see him, and they met on Feb. 9, 1999.

After an exchange of pleasantries (the two knew each other from their time together in Bucharest before Mircea’s arrest), Mircea asked Larry if his description of the Ceausescu meeting was accurate. Larry replied that he could not say anything official about the details of that session. However, he added unofficially that he saw no reason for Mircea to make any changes to the text, as written. And that is the way it appeared in the printed book.

Mircea remains intrigued by the origins of the letter that almost certainly saved his life. What led President Bush to send the letter? Who else was involved in the process? Why Mircea, when many others were in similar positions? Although Bush and Mircea had met when the former was CIA director and the latter served as interpreter for visiting Romanian officials, it would be a stretch to say they knew each other. His extensive efforts to find answers to these and related questions have led nowhere.

Mircea remains intrigued by the origins of the letter that almost certainly saved his life.

Mircea has discovered, however, no other case in which a U.S. president has intervened directly and personally with a foreign head of state or government on behalf of a foreign national who had been spying for the U.S. If that is correct, it makes Mircea’s situation unique.

There is a curious footnote to this story. Mircea somehow got hold of a copy of the Bush-Ceausescu letter, in the original English and as translated into Romanian (the Romanian-language copy bears a stamp from the archives of the Political Executive Committee of the Communist Party’s Central Committee), and included it in the second edition of his book, published in 2009.

When I mentioned this to Larry, by then retired and working as professor of the practice at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University, he was interested in seeing it. He had tried to gain access to a copy of the letter at the adjacent George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum at College Station but had been denied, based on some sort of bureaucratic or security grounds.

Consider that for a moment. The American official who had delivered a letter in person to the late Romanian dictator was not authorized to see that letter! How ridiculous can classification and security restrictions get? With Mircea’s permission, I mailed Larry copies of the letter. The irony was lost on none of us.

Justice finally prevailed, to a degree, in Mircea’s case. In 2000 the Romanian Supreme Court annulled his conviction and sentence, given by the Ceausescu regime. Though friends of Mircea’s had lobbied on his behalf in Bucharest to remove the conviction, he never asked for such interventions, and he himself refused to seek any sort of pardon or clemency, since doing so would be, or could be, construed as an admission of guilt.

In 2001, the Romanian government awarded Mircea the National Order for Merit, with the rank of commander, for his efforts to bring democracy to the country.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.