World’s Fairs Today: A Visit to Milan, Lessons for Dubai

The world’s fair has evolved from an industrial exposition into the Olympics of public diplomacy, and the United States should be there.

BY MATTHEW ASADA

Russia’s pavilion at the Milan expo. Each participating country celebrates a national day during the fair, which usually consists of a high-ranking visit, flag ceremony, tour of the national pavilion, cultural program and parade. The author’s visit to Milan coincided with the Russian national day event, at which Russian President Vladimir Putin and Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi spoke.

Courtesy of Matthew Asada

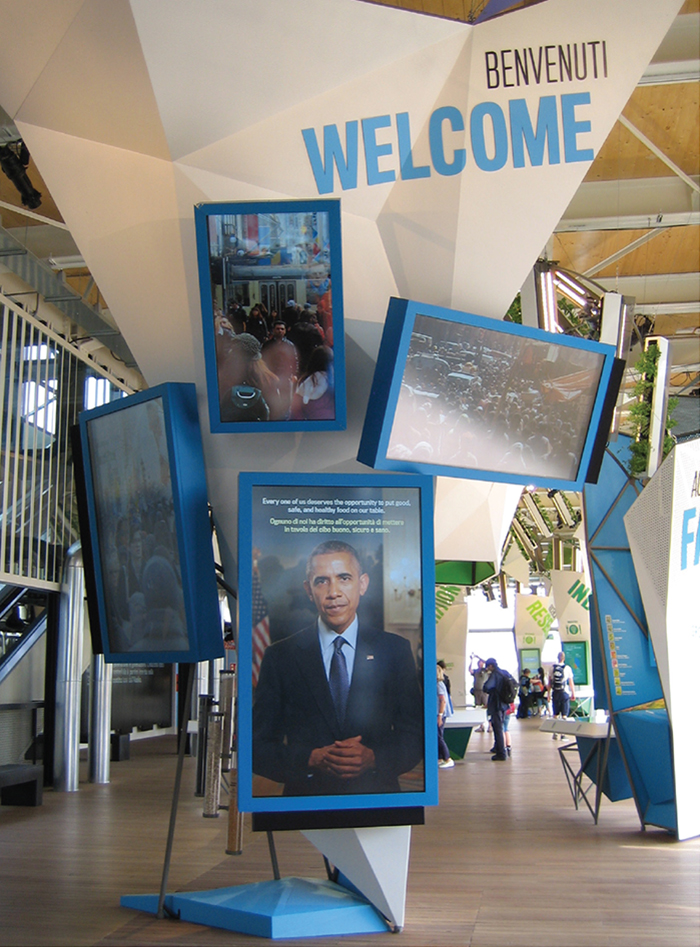

In Milan, the U.S. pavilion’s open-wall structure and green design, informative messaging and personable staff impressed. As in Shanghai, President Obama’s life-size video message was a hit.

Courtesy of Matthew Asada

We still have those?!” a congressional staffer remarked incredulously when I mentioned my recent trip to the world’s fair in Milan. For many American foreign affairs practitioners, world’s fairs, also known as international expositions, are quaint 20th century relics of little 21st-century value. However, while the United States has been cutting back on its participation in recent decades—missing the 2000 fair altogether—the rest of the world has gotten increasingly involved. For those who have never been to a fair, it’s like Epcot on steroids, albeit with diplomats and pavilions focused on current global challenges.

The world’s fair has evolved from an industrial exposition into a public diplomacy platform. At a time when American leadership and commitment are in question, and American values, such as economic opportunity and democracy, are under attack, the United States needs to be present at these fairs—the Olympic games of public diplomacy.

Most millennials have never visited a world’s fair. My first experience was to the Daejeon Expo in 1993. Seven years later, I visited the 2000 fair in Hanover while an intern at Consulate General Frankfurt. I have visited every major world’s fair since: Aichi 2005; Shanghai 2010; and Milan 2015. The absence of a U.S. pavilion in Hanover and my subsequent expo visits have impressed upon me the importance of these events and our continued participation in them.

History of the World’s Fair

The first generally recognized world’s fair was held in London in 1851. Cities vied to host the fair as a matter of prestige, branding and economic development; participating countries built architecturally stunning pavilions to display their latest technological and cultural innovations. Notable fairs include Philadelphia 1876, Chicago 1893 and 1933, Paris 1900, Barcelona 1929, New York City 1939 and 1964-1965, and Osaka 1970. Each fair left behind iconic architecture, such as the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Space Needle in Seattle and the Unisphere in New York City.

In 1928, countries founded the Bureau of International Expositions to administer the organization and certification of fairs. Since 1996, the bureau has authorized a major international exposition, otherwise known as a “registered” world’s fair, to be held every five years. Smaller, minor expositions—or “recognized” fairs—are held in intervening years. According to the BIE, a world expo is meant to showcase “the social, economic, cultural and technology achievements of human beings.”

The United States has hosted 20 major and minor fairs, the first in 1853 in New York City. Several U.S. cities have expressed interest in hosting future fairs; however, these cities may have to wait for some time, since BIE member states are given priority. Though the United States was a founding member, Secretary of State Colin Powell officially withdrew U.S. membership in 2001 after Congress failed to authorize and appropriate BIE dues. Until the 1990s, responsibility for requesting and administering congressional appropriations for U.S. participation in world’s fairs had been the purview of the United States Information Agency.

Congress Limits U.S. Participation

Following the end of the Cold War, members of Congress began to question the need for world’s fairs. Notwithstanding efforts by Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush to secure funding for U.S. participation in the 1992 World’s Fair in Seville, Democrats objected and only appropriated $18 million of the $45 million requested. The reduction forced USIA to drastically revise its plans for the pavilion, and the United States had to make do with an underwhelming pavilion consisting of two geodesic domes—veterans of the European exhibitions circuit—that were dug out of storage. That year, by comparison, the United Kingdom spent $40 million on its pavilion.

In light of the experience in Seville and bipartisan interest in balancing the budget, Congress prohibited federal expenditures on a U.S. pavilion without express congressional authorization and appropriation in 1994. Despite this ban, Tony Coelho, U.S. commissioner general for the 1998 World Expo in Portugal, secured $6.7 million in federal funds from other agencies that covered more than 80 percent of the costs for the U.S. pavilion in Lisbon.

The United States has hosted 20 major and minor fairs, the first in 1853 in New York City.

In 2000, Congress loosened restrictions to allow federal funding of administrative expenses for U.S. participation in Expo Hannover 2000, but upheld the State Department ban on construction and operating costs. Congress viewed the U.S. pavilion as a private-sector responsibility, ignoring the public diplomacy angle and the prevailing practice of other governments providing public financing. Private companies preferred to be thought of as “international” as opposed to American, investing in their own stand-alone, corporate exhibits rather than in the U.S. pavilion. There was also concern that expenditures would be misdirected to BIE.

Despite efforts by U.S. Ambassador to Germany John Kornblum and U.S. Commissioner General William Rollnick, and personal requests from German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder to President Bill Clinton, the U.S. pavilion was unable to raise sufficient private or public funds to participate in Hannover. It was the first fair that the United States had missed since they began in 1851. The German government, fair attendees and other participating countries noticed the U.S. absence. One German state legislator remarked, “Many Germans see this as part of a larger pattern. The feeling is that always when it comes to multinational efforts, the United States has no money.”

The Rest of the World Steps up Engagement

Meanwhile, the rest of the world was stepping up its engagement. Participants no longer viewed the events as industrial trade fairs, but as opportunities to present their foreign policies and brand their countries, promote cultural understanding and address global challenges. Japan spent $3.3 billion to host Expo Aichi 2005, the theme of which was “Nature’s Wisdom.” The expo drew 121 participating countries and 22 million visitors. The United States, however, had a limited pavilion due to its ongoing funding challenges.

One year before Expo Shanghai 2010, it looked as though the United States might miss out again on the opportunity to present a first-class showing, or any showing for that matter. However, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton made it a personal priority to secure U.S. participation in the fair. Ultimately, the Secretary and Commissioner General Jose Villarreal succeeded in raising more than $61 million for the U.S. pavilion and organizing participation in a record-breaking nine months. While some criticized the reliance on corporate sponsors and their resultant influence on exhibit content, the United States made it to Shanghai.

China spent $48 billion on the 2010 fair, more money than it spent on the 2008 Summer Olympic Games in Beijing. Its theme was “Better City, Better Life.” With 190 countries participating and 73 million visitors, Shanghai broke Osaka’s 1970 attendance record. More than 7.3 million visitors came through the U.S. pavilion; most were Chinese nationals, many of whom had never been to, nor would probably ever visit, the United States.

Secretary of State John Kerry similarly prioritized U.S. participation in the 2015 World’s Fair in Milan, “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life.” The United States expected three to five million of the fair’s total 25 to 30 million visitors to visit the U.S. pavilion during the fair’s six months of operation.

Congress prohibited federal expenditures on a U.S. pavilion without express congressional authorization and appropriation in 1994.

Organizational Architecture behind the U.S. Pavilion

The Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs assumed responsibility for U.S. participation in world’s fairs after the 1999 merger of USIA with the Department of State. At that time, USIA disbanded its five-person office that had been responsible for developing exhibit content, managing relations with the BIE and providing logistical support for the pavilion itself.

For Milan, in a first for U.S. government expo-logistics prep, ECA delegated oversight authority to a regional bureau, the Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs. Barry Levin, a retired Foreign Service officer who had worked on the smaller Expo Yeosu 2012, handled initial preparations for Milan. The pavilion itself would be constructed, designed, organized, managed and removed by Friends of the USA Pavilion Milan 2015, a private consortium that won the department’s request for proposals in July 2013.

In March 2014, Bea Camp, U.S. consul general in Shanghai at the time of the 2010 fair, was recruited as coordinator of the U.S. pavilion in Milan within EUR’s Office of Public Diplomacy. As the only officer assigned in Washington to work on the expo, Camp advises the department, Consulate General Milan and the private-sector team on a range of issues, from determining appropriate content to vetting sponsors. She also coordinates the department’s public messaging on U.S. participation in the expo.

In December 2014, Secretary Kerry appointed San Francisco venture capitalist and Obama fundraiser Douglas Hickey as commissioner general for the Milan Expo. Hickey, temporarily accorded the rank of ambassador, is the U.S. pavilion’s chief diplomat, fundraiser and executive officer.

While other national pavilions have a robust diplomatic presence, the U.S. pavilion has just one dedicated Foreign Service officer, Elia Tello, who holds the title of deputy commissioner general. Working closely with Consulate General Milan and Embassy Rome, Tello coordinates programming and logistical support for official U.S. visitors. For instance, First Lady Michelle Obama visited the U.S. pavilion during her trip to Milan in June and underscored the importance of the fair’s theme by speaking on food security, health and nutrition.

Hickey and Tello work alongside 120 bilingual American college students who, through the Student Ambassadors Program, serve as the pavilion’s primary staff, greeting visitors and walking them through the exhibit.

During my June visit to the expo, I had the opportunity to speak with Commissioner General Hickey and tour the U.S. pavilion. Ambassador Hickey commented that one of the reasons people were responding so well to the fair was that it is easy to get one’s head around the theme of food diplomacy. “The challenge for future fairs will be to find a relatable theme that will harness the same sort of energy.” Given his professional background, he thought that innovation, technology and entrepreneurship could be promising themes. Perhaps he had his hometown in mind when he spoke; San Francisco has expressed interest in hosting the 2025 expo.

Food has always been part of the expo-goers experience, but especially for this important food-centered fair. The U.S. pavilion food trucks in Milan lacked identifying decoration due to their rotating menus—a bit disappointing given the creativity displayed by other countries (the Dutch food trucks were hard to beat).

Courtesy of Matthew Asada

State should establish a permanent two-person unit that is then temporarily embedded into whichever regional bureau is hosting the next expo.

Recommendations for Dubai 2020

The next minor and major expositions will be in Astana in 2017 and Dubai in 2020, respectively. Dubai expects roughly 25 million visitors, 70 percent of them from overseas. The expo will also launch the country’s Golden Jubilee celebrations. It is crucial that the Department of State begin preparing immediately to maximize the public diplomacy opportunities of robust U.S. participation.

Ever since USIA consolidation, and the resulting retirement of its institutional memory, the department has had to bureaucratically reinvent the wheel every time there is a major or minor fair. This takes time and energy away from pavilion design, content and programming. While ECA has authority to manage U.S. participation per the Fulbright-Hays Act of 1961, the Bureau of International Information Programs might be a more logical home given its responsibility for the U.S. government’s American spaces and platforms. State should establish a permanent two-person unit in ECA or IIP that is then temporarily embedded into whichever regional bureau is hosting the next expo.

The department should consider creating more one-year domestic and overseas assignments for Foreign Service personnel to be involved in content creation and delivery of material at the pavilion. Finally, IIP should develop a specific world’s fair campaign to push out to posts to maximize coverage in local press about U.S. and host country participation.

In 2009, Congress authorized establishment of Brand USA, the United States’ first tourism promotion agency. Funded by a $10 surcharge on every international airline ticket, the agency promotes tourism to all 50 states. While Brand USA contributed to the content development and construction expenses of the U.S. pavilion in Milan, there is greater scope for collaboration in Dubai, given the shared interest in public diplomacy and tourism promotion and Brand USA’s independent, non-appropriated, fee-driven revenue stream.

Finally, it is time for the State Department and the next administration to request federal funds for the construction and operation of a U.S. pavilion as part of a true public-private partnership and to rejoin the Bureau of International Expositions to increase the chances that a U.S. city will be chosen as a future host.

Now is the time for public diplomacy investments to tell our story, explain our policies and mobilize humanity to address our global challenges. This year the United States will spend tens of millions on countering violent extremism. Perhaps a small portion of that should go toward U.S. participation at the next Public Diplomacy Olympics—the 2020 World’s Fair in Dubai.

Read More...

- American Food 2.0: USA Pavilion 2015 (Friends of the USA Pavilion Milan 2015)

- Expo Milan 2015 (Expo2015.org)

- At World's Fair In Italy, The Future Of Food Is On The Table (NPR, May 31, 2015)

- How the ‘World of Tomorrow’ Became a Thing of the Past (TIME, April 29, 2014)

- The History of World's Fairs (ExpoMuseum)

- Remarks by Senior Advisor for International Affairs Bea Camp to the Public Diplomacy Council regarding U.S. participation in the 2010 Shanghai Expo (Nov. 3, 2011)