Foreign Service Women Today: The Palmer Case and Beyond

Women have made great strides, but more effort is needed to fulfill the legal mandate for a Foreign Service that is “truly representative of the American people throughout all levels.”

BY ANDREA STRANO

The struggle for equality of opportunity for Foreign Service women has been long and lively. Ignited by legal challenges by Alison Palmer in 1968, it continues today.

Tremendous progress has been made. Fifty years after the first female member of the Foreign Service, Lucile Atcherson, was admitted in 1922, women still made up less than 10 percent of the diplomatic corps and faced systematic discrimination at the State Department. Today, women comprise 35 percent of the overall Foreign Service (including officers and specialists) at all foreign affairs agencies and 40 percent of the Foreign Service officer corps. Starting with the requirement for female FSOs to resign when they get married, most of the institutionalized discrimination in hiring, pay, promotion and other personnel policies has been overturned.

Yet there remains a lingering bias against women that is more subtle, more difficult to get at. Often reported anecdotally, that bias is also concretely reflected in such metrics as the male-female gender breakdown by rank—as ranks increase, female representation decreases. And though 40 percent of FSOs are women, they hold only one-third of the chief-of-mission positions, for example.

The Foreign Service Act of 1980 mandates a diplomatic service that is “truly representative of the American people throughout all levels of the Foreign Service.” State Department leadership has acknowledged the benefits of a diverse workforce and demonstrating U.S. values to other countries through its people. However, true representation remains elusive, including for women.

The result is a Foreign Service that is not yet benefiting from the full strength of the country that it represents.

Standard Bearer and Firebrand

Alison Palmer, who joined the State Department in 1955, launched the legal battle for female equality at the State Department in 1968 with the first equal employment opportunity (EEO) complaint ever heard from the Foreign Service. She followed her 1971 victory in that case with a class-action suit on behalf of all women in the U.S. Foreign Service in 1976. Today’s impartial entrance criteria, evaluation and promotion policies, and assignments processes all stem in large part from “the Palmer Case,” which was fought in various phases over more than 30 years.

During the same period, Palmer’s spiritual journey led to her collaboration with other women to enter the Episcopal Church priesthood, and she was “irregularly” ordained in 1975. When she retired in 1981, after a 26-year career in the Foreign Service, Palmer was an FS-3. In her autobiography, Diplomat and Priest: One Woman’s Challenge to State and Church (CreateSpace, 2015) and in a series of interviews with the author, Palmer describes her experience.

After three written rejections from ambassadors in Africa, Palmer, an African affairs specialist, had tried for a position in Addis Ababa in 1966. As she put it in the interview, her assignments officer wrote the ambassador that, though he might be “surprised that we would consider sending a girl to Addis,” he could be assured that “given her superb record and qualifications, we believe she will fill the job splendidly.” The ambassador permitted Palmer a position at post in Ethiopia—as social secretary to his wife.

Two years later, Palmer showed up for her first day in an FS-4 position in Washington, D.C., only to be told she would instead assume a position two grades lower because a lower-ranking male colleague needed the position as a path to promotion. “I used to tell women to not join the Foreign Service because their talents wouldn’t be used,” Palmer says.

Palmer’s 1968 EEO complaint charged the three ambassadors with discrimination, yet the four-page memo submitted by the State Department investigator did not name them. In 1969, the State Department found in her favor, but Palmer demanded a change in personnel policies, a retroactive promotion and a review of State’s EEO Office.

With the help of the American Federation of Government Employees, Palmer appealed to the board of the Civil Service Commission, the federal employment entity that was later replaced by the Office of Personnel Management, the Merit Systems Protection Board and the Federal Labor Relations Authority. After hearings in the summer of 1971, the board decided in her favor. She received the promotion and retroactive pay, which she used to fund the class-action lawsuit she filed in 1976.

Implicit and explicit bias in the performance evaluation and promotion system was one of WAO’s primary targets.

Parallel Strides

Meanwhile, Palmer and other members of an “ad hoc committee to improve the status of women” (which would later become the Women’s Action Organization) continued to work separately and together for Foreign Service equality on a number of fronts.

In 1968 the ad hoc committee demanded that State appoint a women’s coordinator to monitor and implement the Federal Women’s Program the Johnson administration had established to promote female employment in the federal government. The department complied, naming Elizabeth Harper as a part-time coordinator and establishing an official committee that included Jean Joyce, a founder of the WAO; Alison Palmer; and Barbara Good, an American Foreign Service Association board member and a founder and president of the WAO. “The timing of this mandated program greatly facilitated WAO’s effort to press for change,” Good wrote in the January 1981 Foreign Service Journal (“Women in the Foreign Service: A Quiet Revolution”).

At its official formation in 1970, WAO resolved to be an independent, voluntary organization that would work, in the words of Good, “not by confrontation or militancy, but by dealing directly with management to bring about reform” that would serve all categories of women in the three foreign affairs agencies—State, USAID and the U.S. Information Agency. The organization worked closely with AFSA to eliminate the policy banning married women from the Foreign Service and secure reappointment for those who had resigned—a goal that was achieved in 1971.

According to Good, WAO members disagreed with Palmer’s “militant” approach. After her EEO victory in 1971, which benefited all Foreign Service women, the group split over support for the class-action suit. “After long discussion,” Good notes in her FSJ article, WAO became “a somewhat silent partner” in that suit and, at the same time, continued to work “within the system, using sustained pressure to achieve our aims.”

Implicit and explicit bias in the performance evaluation and promotion system was one of WAO’s primary targets. In 1980, the group circulated Lois W. Roth’s research paper, “Nice Girl or Pushy Bitch: Two Roads to Nonpromotion,” charging that performance ratings often institutionalized discrimination against women and remained crucial obstacles to equal opportunity and promotion. It is necessary to “help men understand,” Roth states, “that their ‘kind and supportive’ remarks about women officers often perpetuate myths and values that get read in the promotion process as weakness, and that in calling us ‘pushy’ or ‘abrasive’ when we are properly ambitious, they are using a double standard that does us great disservice and, ultimately, does them dishonor.”

WAO achievements include a reduction in the inequity in overseas living arrangements, increased recruitment of women into the Foreign Service, increased representation of women on promotion boards, elimination of references to gender and marital status in performance evaluations and establishment of the spouses’ “skills bank”—the precursor of today’s Family Liaison Office.

The Palmer Case Makes Progress

In 1985, the U.S. District Court decided the class-action suit in favor of the State Department, but two years later the U.S. Court of Appeals overturned that decision in favor of the plaintiffs. Having been found to have discriminatory personnel practices (e.g., women were assigned more often to consular work than political; women were disproportionately refused assignment as deputy chief of mission; and women’s nominations for “superior” awards were downgraded to “meritorious” awards), State agreed to make changes.

Foreign Service hiring practices had yet to be examined, however, and in 1989 the Foreign Service entrance examination process came under scrutiny. In a court order that year the U.S. District Court found that “the Department of State had discriminated against women in the administration of a written examination that applicants for positions in the Foreign Service were obliged to take.” The court mandated that State not use Foreign Service Officer Test results from 1985 to 1987. State was ordered to grade the 1988 exams to eliminate discrimination against women, and the 1989 exam was canceled.

In 1991, the same court again found discrimination in the FSOT. As restitution, 390 women who had the highest non-passing scores for the 1991–1994 Foreign Service written examination were invited to participate in the oral phase of the application process in 2002. Of those who participated, 11 were admitted to the Foreign Service with back pay plus interest and credited years of service toward retirement.

Through the 1990s and 2000s, State worked to improve personnel procedures and processes as mandated by the court. In 2007, the court ordered State and Palmer to begin to settle the suit, which was finally dismissed in 2010—34 years after it had been filed and 42 years after Palmer’s first EEO complaint. In the end, State had either ceased the unfair practice or made progress on such problems as unfair out-of-cone and initial cone assignments and underassigning of women to stretch and DCM assignments; disproportionate promotions; discriminatory hiring practices and processes; and reclassification of awards. State also introduced an improved performance evaluation form and instituted a high-level Council for Equality in the Workplace, which is now the Secretary’s Office of Civil Rights.

None of those named in the case, nor anyone in a leadership position at the State Department, was ever held accountable for the systematic discrimination the court found.

The Scant 33 Percent

Women at Work

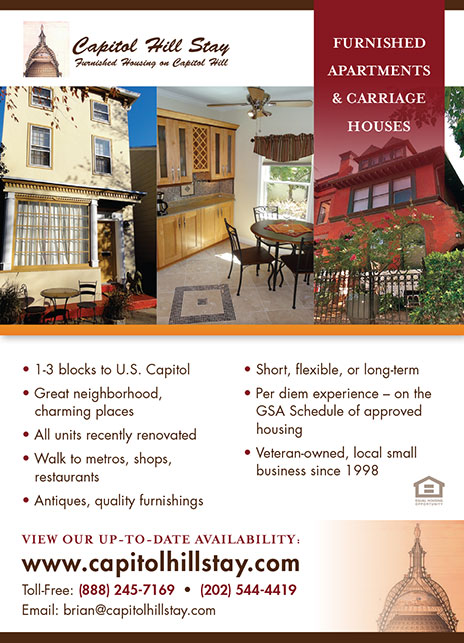

Women comprise:

50.8% of the U.S. population

47% of the U.S. workforce

40% of Foreign Service officers

35% of Foreign Service members, including officers and specialists at all Foreign Service agencies

33% of U.S. ambassadors

31% of senior State Department positions

Sources: U.S. Census, 2010; Department of Labor, 2010; Department of State, Office of the Director General.

In September 2015, Foreign Service Director General Arnold Chacón trumpeted on his Twitter feed that one in three chiefs of mission is a woman. The figure shows progress from the past, no doubt, but is less impressive in light of the fact that 40 percent of Foreign Service officers are women. The current cohort of female ambassadors also includes a large number of political appointees, rather than women promoted from within the Foreign Service.

“Currently EW@S’s challenge is to demonstrate to State Department leaders—many of whom are female political appointees—that there is a problem,” wrote Executive Women @ State’s Susan Stevenson in the June 2015 Foreign Service Journal. During an October 2015 open forum that Secretary of State John Kerry cohosted with EW@S and S/OCS, the Secretary promised exit interviews, to begin early this year, as a means to understand reasons for separation.

According to the Office of the Director General, State bureaus and other Foreign Service agencies will ask all Foreign Service and limited non-career appointment employees to complete the exit survey as part of the check-out process. Those who leave State’s Civil Service will be interviewed, as well.

While important to track, women’s rate of attrition—their departure from the Service—will not fully explain the lower number of female leaders. According to the Office of the Director General, men and women both leave at a rate of 3.5 percent, “as has been the case for many years.”

Attention has turned to promotion biases, the topic of a series of focus groups S/OCS conducted in 2015. There, the majority of more than 60 participants reported that caregiver bias still affects female advancement. Women asked for more flexibility from promotion deadlines, known colloquially as “up or out.”

Senior Foreign Service Officer Margot Carrington, who examined both female retention and promotion during her Una Chapman Cox Foundation fellowship from 2010 to 2011, reviewed private-sector solutions to problems in these areas (see her “How Are FS Women at State Faring?” in the May 2013 FSJ.)

One company’s assumption, that women left the firm during caregiving years to work part-time or not at all, was upended when research showed that women were, in fact, continuing their careers; but they were doing so elsewhere, where they found more flexible work situations. The company then changed its promotion model and successfully retained more of its talent. Carrington recommends examination of the “up or out” deadlines, and asks whether the series of linear and progressively more challenging positions is ultimately discriminating against family caregivers, no matter the gender.

Recently, high-profile opinions have surfaced about whether women can “have it all” or whether they should “lean in” at strategic times of life. Though these debates among women about their own life choices and paths are separate from the particular questions of hiring and promotion, they are relevant to attracting and retaining a diverse Foreign Service.

The Great Promotion Taper

In a 2010 study, the organization Women in International Security found “a pronounced and persistent gender gap in the Senior Foreign Service.” While some statistics indicate improvement in women’s representation in higher-ranking roles, others show otherwise.

In a study of the data from 1994 to 2014, State’s Bureau of Human Resources found that women’s promotion has been proportionate to their percentage when they entered the Foreign Service. “Female cohorts are moving from entry level to senior level in proportion to their hiring,” the HR report states. “The senior level of today is the entry level of 20 years ago.”

However, according to a more detailed breakdown of promotion statistics for 2014, confirmed by the Office of the Director General, the disparity in the rate of promotion in the higher ranks was significant. Of the women who competed for promotion from Counselor (FE-OC) to Minister Counselor (FE-MC) that year, 23.9 percent were promoted. Of the men who were eligible for the same rank, 30.3 percent were promoted. As the rank increases, the proportion of eligible women who compete decreases: Of the 379 officers who competed for promotion from FS-1 to FE-OC, 33.5 percent (127) were women; of the 161 who competed for FE-MC to Career Minister (FE-CM), 27.3 percent (44) were women.

Are fewer women promoted to leadership roles because they choose not to compete for higher rank, or are additional training and professional development required to aid in their quest? Additional research can help to answer that question.

While important to track, women’s rate of attrition—their departure from the Service—will not fully explain the lower number of female leaders.

Ambassador Jennifer Zimdahl Galt, who has served in Asia, South Asia, Europe and Washington, D.C., beats the drum for women stepping up for senior promotion. “When women put themselves forward, they compete well at all ranks of the Foreign Service,” Galt said in an interview. “I would like to see more senior women mentoring younger female officers and guiding them to bid on senior positions.” At an open forum in October, DG Arnold Chacón announced his approval of a Cox Foundation study to identify gaps in, and make recommendations for, mentoring opportunities at the department. Also, senior-ranked women plan to discuss ways to promote women’s mentorship at the March Chiefs of Mission conference, but on the margins rather than as part of the main agenda.

Not all embrace mentoring. Palmer, for instance, stated during an interview that she believes mentoring programs are a means to cope with and, in effect, enable inherent problems in an organization. “If you have to mentor a group, it means they’re already not getting fair treatment. They’re the result of a poor personnel system that is not based on merit.”

Situational Sexism

There is another phenomenon within the Foreign Service that can perhaps best be described as situational sexism, in which circumstances are sometimes used to justify biases against women in the name of cultural sensitivity and practicality. The societal gender restrictions of the Middle East and parts of South Asia have offered a particularly fertile environment for this phenomenon historically.

Admittedly, along with the Bureau of African Affairs, the Bureaus of Near Eastern Affairs and South and Central Asian Affairs have the highest percentages of female leaders in Washington and at posts today. Department leadership in both bureaus is 28 percent and 33 percent female, respectively, including both assistant secretaries. Female chiefs of mission lead 33 percent of the NEA posts and 44 percent of SCA posts.

Yet in reaching out to 15 female FSOs who have worked in these regions, six mentioned that they’ve seen some male colleagues slip into discrimination once they are surrounded by a sexist culture, in the name of working effectively in the country.

Ironically, as the women point out, they are, in fact, accepted by local male leaders as “a diplomat” or “a third gender” and can therefore meet and report as successfully as men. “We can meet with the local men in their majlis (meeting rooms) and the women in their own groups,” says one female FSO, who prefers to remain anonymous. She voices frustration with what she calls the current practice of treating women as a specialty population to consider solely for women’s issues reporting.

When officers meet with women, she says, they can provide fuller reports of the political, economic and security situation. She routinely asks, for instance, about the welfare of the children, whether they attend school and, finally, whether they walk to school. “That one answer tells me something about security on the ground,” she says. “If it’s safe, the kids can walk to school.” At times, this subject has led to more pointed intelligence: “I’ve been told, ‘We don’t like the kids walking past that house over there because there are these strange guys who moved in last month.’ And suddenly, we would have new suspicious actors to watch.”

Joanne Cummings, who served as the first Foreign Service refugee coordinator in Iraq in 2004, makes a similar point, citing her meetings with displaced families. One group of men asked her for a generator, but the women indicated they needed a water tank: The girls of the village had been attacked while walking miles to the nearest water source. When told of the men’s request for a generator, she says, “The women started laughing. ‘Oh, they want to watch TV!’” Cummings adds: “Now, if I’d been a well-prepared male FSO, I would’ve provided the generator. And I would have been doing my job. But how often have we gotten things seriously wrong because we’ve restricted ourselves to talking to half the people in a country to get the whole picture?”

Representative Representation

Many have observed that a Foreign Service that better represents the United States will improve policymaking, reporting and analysis. Contributions that women bring to senior ranks are informed by diverse experiences that men do not share. The examples from posts in the Middle East support this claim.

In a November 2014 interview for the Public Broadcasting System’s “To the Contrary,” Assistant Secretary for African Affairs Linda Thomas-Greenfield said, “It is important for the world to see the face of America. They need to understand that we are a diverse society and that diversity is our strength.”

The exit interviews that Secretary Kerry promised may help identify lingering barriers. There has long been a need to hear from female FSOs on their way out the door, but no one asked. Those women who remain in the Foreign Service—officers and specialists from State and the other foreign affairs agencies—should all continue to be tapped for more data, as well.

Continued investigation is needed to make appropriate, relevant personnel policy adjustments. “When the final settlement was made in 2010, I felt glad that I had accomplished something,” Palmer writes in her autobiography. “But I knew full well that many more decades would pass before women FSOs achieved the equality that is required by law.”

With shrewd effort, today’s discussions can turn good intentions into constructive action.

Read More...

- Toward a Foreign Service Reflecting America by Lia Miller (The Foreign Service Journal, June 2015)

- AFSA Ambassador Tracker: Female U.S. Ambassadors

- Under Pressure, State Department Moves to End Its Sex Discrimination (The Washington Post, April 21, 1989)

- Minorities and Women are Underrepresented in the Foreign Service (GAO Report to the Congress, June 1989)