Fighting Pandemics: Lessons Learned

State’s new, multitiered pandemic response mechanism is the result of understanding and applying lessons learned during the past decade.

BY NANCY J. POWELL AND GWEN TOBERT

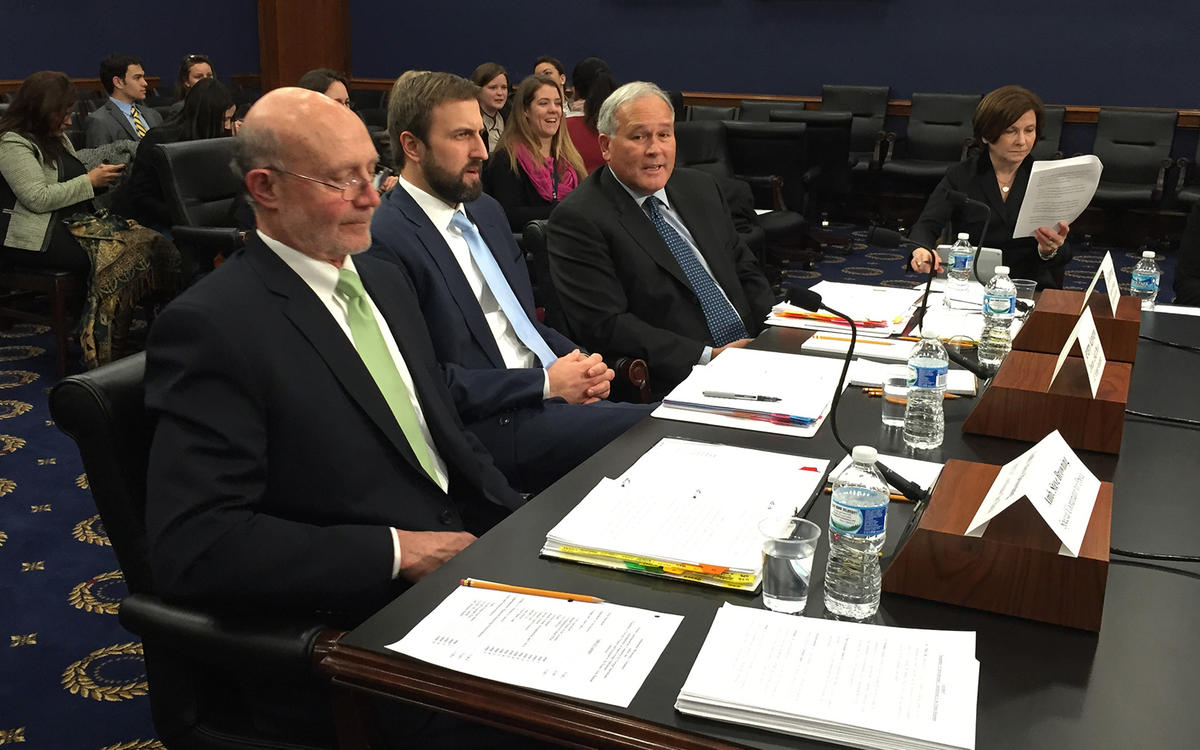

From left, Ambassador Steven Browning, Jeremy Konyndyk (head of USAID's Office of Disaster Assistance) and Dirk Dijkerman (head of USAID’s Ebola Secretariat) testify about funding for the Ebola crisis before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Appropriations on Feb. 11, 2015.

Courtesy of Gwen Tobert

In the past decade, we’ve fought multiple global disease outbreaks, from avian influenza to Zika. One of the most important lessons we’ve learned is that there will be more pandemics in the future, and they are likely to be increasingly complex, particularly if they occur in areas where medical services are already challenged. Beyond the front page stories of human suffering, there can be significant economic and political stability costs if pandemics are not quickly controlled.

In a world of increasing connectivity, it took only weeks for the 2014 outbreak of Ebola in a remote border area of three West African countries to reach Dallas, Texas, via a traveler from Liberia. After arriving in Dallas, the man began developing symptoms and went to the hospital, where two nurses became infected and many others were exposed before doctors recognized his illness as Ebola. The incident sparked public hysteria and political pressure to implement restrictions on travel and trade.

The 2009-2010 H1N1 swine flu outbreak infected more than 60 million Americans, according to an estimate by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and 87 percent of the resulting deaths occurred in those under 65 years of age. Direct economic impacts are difficult to calculate, but numerous studies indicate that a severe pandemic influenza outbreak could cost billions of dollars in GDP loss. If not quickly addressed, infectious disease outbreaks can have significant consequences for our national security, as well.

Looked at through this lens, it is easier to see why the State Department must take a leading role in coordinating the U.S. government response to international public health emergencies. Indeed, as with many deals reached and crises averted in the international arena, there is a diplomat behind each deployment of health-care workers and each development of a new vaccine.

Diplomats bring partners to the table. They expedite processes. They keep trade flowing and share the latest information from the field. And when the doctors and television cameras go home, diplomats stay behind, advocating social and economic recovery to return countries to a positive development path. During the 2014 Ebola crisis, more than two dozen State Department bureaus and offices, in addition to embassies across every region, contributed to the response and recovery effort.

Yet, despite some successes and ongoing efforts to improve early warning and response systems, the international community and the United States remain woefully unprepared to deal with pandemics. It is essential that the State Department continue to press forward energetically with implementation of our own lessons learned so that we can more quickly, nimbly and effectively support our interagency and international partners while protecting the safety of our own personnel in the field.

Recent Advances

In the months after Ebola faded from the headlines, State forged ahead with testing and adaptation of solutions in real time as we responded to new outbreaks of Zika and yellow fever. As a fundamental first step, the Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs (OES) established a small, permanent Pandemic Response Team with a three-pronged mission: to coordinate department-wide responses to outbreaks, build internal capacity and support strategic initiatives around global response capability.

To date, the department’s response to outbreaks has been largely ad hoc, as evidenced by the hodgepodge of “task force” models that have been established—the Avian Influenza Action Group in 2005, the Ebola Coordination Unit in 2014 and the Zika Coordination Team in 2016. The absence of a defined model has repeatedly resulted in a scramble to develop coordination mechanisms and establish leadership in the early days of an outbreak. OES’ Pandemic Response Team seeks to address this challenge as a central tenet of its mission to build State Department capacity. Together with the Bureau of Medical Services (MED) and the Operations Center’s Crisis Management and Strategy Office, the team has now launched a multitiered response mechanism that mirrors best practices at agencies like the CDC and integrates pandemic response into the department’s broader crisis management structures.

To date, the department’s response to outbreaks has been largely ad hoc, as evidenced by the hodgepodge of “task force” models that have been established.

This new model provides a framework for elevating the department’s response posture from “steady state” monitoring by the Pandemic Response Team up the ladder to establishment of an Operations Center Task Force and, potentially, creation of a separate coordination office along the lines of the Ebola Coordination Unit. Outbreaks have complex policy implications, and they may ebb and flow over a period of many months; the goal of this model is to provide predictability while maintaining maximum flexibility and ensuring a judicious expenditure of resources.

In addition, a new Public Health Working Group, co-chaired by OES and MED under the auspices of the State Department Crisis Management Council, brings together representatives from across the department to evaluate outbreaks and provide advice to senior officials on appropriate responses. Emergency Action Committees at posts utilize tripwires to determine responses to any given threat; in a similar manner, the working group relies on a set of decision criteria to assess the risks posed by a potential outbreak.

This decision tool incorporates criteria such as the overall public health threat level, the extent of U.S. mobilization required, public perceptions, existing capacity within State Department offices, expected impact on post staffing and U.S. nationals overseas, and expected political and economic consequences to affected regions. Through the co-chairmanship of OES and MED, the working group also helps ensure that critical operations and management issues are integrated into policy decision-making.

The PHWG formalizes another best practice learned during previous outbreaks: it maintains a network of contacts embedded throughout the State Department to facilitate rapid information sharing and to feed analysis across State’s broad equities into the U.S. government policymaking process. Regular meetings of this group provide a forum to resolve ongoing public health crisis management challenges and to flex the department’s coordination muscles before an outbreak occurs.

Mirroring these efforts within the department, the Pandemic Response Team also develops and maintains strong working relations with interagency counterparts (including the National Security Council, CDC, USAID, Department of Defense, Department of Transportation and Department of Homeland Security), as well as with key allies and the World Health Organization, to support its three mission areas. These working relationships are essential to preparedness training, as well as better communication, coordination and transparency during an emergency.

Through these relationships, the Pandemic Response Team monitors global disease outbreaks and local responses to provide senior officials with an early warning when outbreaks may require a U.S. or international response. The team also leverages these relationships to support State’s Bureau of International Organizations in encouraging and monitoring efforts to reform WHO’s emergency response capabilities.

More Work Needed

Nicolette Louissaint (left), Gwen Tobert (center) and Robert Sorenson, the three core staff of the Ebola Coordination Unit, at a February 2015 event where President Barack Obama honored those leading the Ebola response effort.

Courtesy of Gwen Tobert

The State Department has made demonstrable progress in acting on the lessons learned during the last decade, and there is tremendous opportunity for the new leadership to bolster these achievements. In particular, with stronger structures now in place, the department should take a closer look at the human capital and processes within those structures.

• First, networks need to be encouraged at all working levels. The State Department excels at building relationships that bear fruit months or even years down the road, and this is a unique asset that both our Foreign Service and Civil Service colleagues can offer the interagency in times of crisis. Contacts developed with the international health community during the avian influenza effort paid dividends during the Ebola crisis, and Ebola contacts greatly facilitated the response to Zika.

Cooperation on Ebola was facilitated by relationships developed among State, USAID, DoD and World Food Programme officials during earlier service together in Nepal. Personal relationships, developed over years of working together, greatly assist in breaking down the normal barriers to interagency and international efforts. These networks may develop organically, but they can also be encouraged through trainings and exercises.

• Second, State should maintain a roster of current and retired ambassadors with strong management and team-building skills, who can be called on to head a separate coordination office when the highest level of departmental response becomes necessary. The ambassadorial title is invaluable in interagency and international arenas during a complex public health and humanitarian crisis such as Ebola, and the need for strong organizational skills far outweighs the need for scientific or health credentials, which should be supplied by other members of the team.

Seasoned career ambassadors also bring critical personal relationships to the table. During the Ebola outbreak, for example, Ambassadors Deborah Malac and Linda Thomas-Greenfield leveraged personal relationships with Liberia’s senior leaders to enhance our ability to support the government and secure its support for our assistance effort.

• Third, we need to make it easier for State officers to volunteer to serve on a task force or in a coordination unit, especially for extended periods of time. Given workforce shortages, it is likely that any task force or coordination unit is going to be very diverse and not necessarily experienced in international health—and that’s OK. The establishment of the Pandemic Response Team—and OES’ commitment to lead a task force with MED support if one is stood up—ensures that the core team will have the necessary expertise, but additional personnel will surely be needed. Pandemic response requires expertise in the areas of geopolitical, consular, legislative and public affairs, among others. It also requires skilled staff assistants, office management specialists and management officers.

The Ebola Coordination Unit eventually consisted of two OES civil servants whose permanent assignments involved international health issues, an ambassador-designate awaiting confirmation, an American Association for the Advancement of Science Fellow with an advanced degree in pharmacology, a Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs evacuee from Yemen, a medical evacuee, an unassigned management officer and an office management specialist temporarily reassigned to support the team from the Office of the Counselor.

What we lacked in experience was more than made up for by dedication and long hours. This shouldn’t be a surprise—it’s the norm for State Department crisis management. Yet though this rag-tag team delivered month after month, burnout was a very real issue, and the ECU lacked a mechanism to rapidly transition in new staff, particularly those with skillsets matching current needs.

State has made demonstrable progress in acting on the lessons learned during the last decade, and there is tremendous opportunity for the new leadership to bolster these achievements.

• Fourth, State must continue to affirm its role within the interagency community during a pandemic. The department’s forward-leaning approach and reliable support in recent outbreaks has strengthened its reputation as coordinator and facilitator, as well as expanding the interagency’s appreciation of the numerous foreign affairs equities involved in any successful response. State’s seat at the interagency table provides a window into the complexity of a pandemic, particularly after it hits America’s shores, allowing senior State representatives to shape the response even if some measures are outside of their immediate mandate.

Each outbreak will be unique, and we do not yet know how current or future administrations will choose to structure the U.S. government’s overall response. During the avian influenza outbreak of 2005, State took on a coordination role, leading an interagency task force that worked to support the international response. By the time the Ebola Coordination Unit was established in 2014, the National Security Council was clearly in charge of a multiple-agency effort that included deployment of military personnel, civilian health and development professionals, and large numbers of nongovernmental organization workers.

State’s role was much more narrowly defined. We supported the president’s and the Secretary’s efforts to secure financial and other support; participated in press events and congressional briefings; coordinated with the United Nations as they slowly built up a presence in West Africa; helped formulate policies concerning travel to and from the affected areas; and coordinated with embassies in the affected areas. Each time a State task force or coordination unit is established, senior State officials should determine what role State will play and convey that clearly to the ambassador, the regional bureaus and other agencies.

Strategic Approach Needed

Finally, to return to our first lesson learned, State’s senior officials must think strategically about mitigating the impact of future, and potentially more frequent, pandemics on the department's mission.

State needs to maintain—even in the face of anticipated budget cuts—the Pandemic Response Team and the broader Office of International Health and Biodefense, which works to increase other countries’ capacities to prevent, detect and respond to infectious disease outbreaks on their own. Regional bureaus, MED, Human Resources and Diplomatic Security need to plan for greater flexibility in meeting posts’ needs and requirements for evacuations, changes in staffing (increases in some areas; reductions in others) and visits by the regional medical officers; as well as plan for potential long-term effects on bidding patterns.

Our diplomatic engagement was essential during the Ebola outbreak, and the State Department must continue to form the backbone of international efforts aimed at better preventing, detecting and responding to the infectious disease threats of the future. It is a matter of national security.