The Foreign Service Responds to COVID-19

Dispatches from the field show how the U.S. Foreign Service works for the American people.

The novel coronavirus has presented a unique challenge to the U.S. Foreign Service. The virus spread widely before being officially recognized as a global threat and pandemic.

As Washington scrambled to develop guidance and manage the response, U.S. embassies around the world had to improvise and come up with appropriate plans of action. Foreign Service personnel posted overseas and in Washington, D.C., worked on an emergency basis to bring stranded American citizens back to the United States safely, while at the same time dealing with the need to protect themselves and their families.

We reached out to the field to ask how the Foreign Service is responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and what impact it is having on individuals, posts and work. Here is a selection of the stories and photos we received.

—Shawn Dorman, Editor-in-Chief

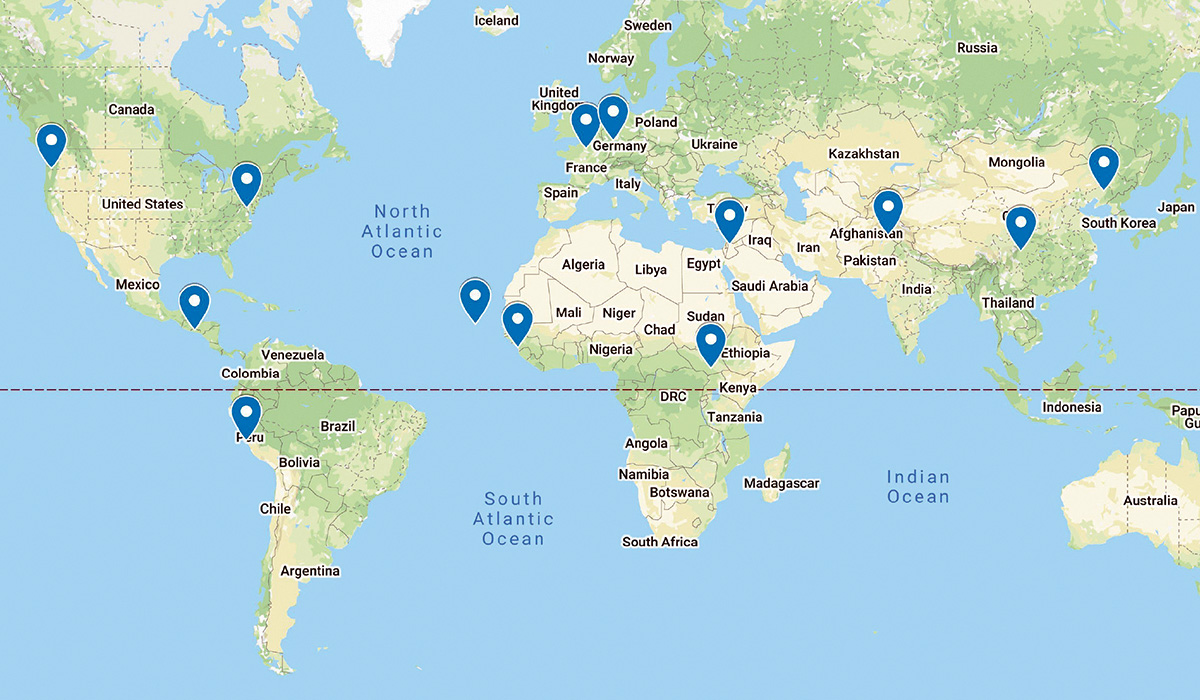

Pinpoints on this world map mark the locations of the contributors to this collection of stories.

Map Data © 2020 Google Map

Tandem Foreign Service Officers Alan Eaton and Timothy Reifenberger from U.S. Consulate Chengdu, part of the Flyaway Consular Team in Wuhan, China, right before the boarding of more than 200 passengers on the first COVID-19-related repatriation flight, Feb. 3.

Alan Eaton

One Long Day

Alan Eaton

Chengdu

My husband and I heard the call for consular volunteers to assist with evacuating American citizens out of Wuhan. We were already in Chengdu and hopped on a plane to Seoul to meet the evacuation team and plane. In the first and only planning meeting we attended, Dr. William Walters of State’s Office of Operational Medicine said: “It is a privilege to get to do the hard things.”

For the next 96 hours, we transited from Seoul to Wuhan and on to Travis Air Force Base, California, and then back to Seoul; to Wuhan again, and on to Vancouver and Miramar Joint Base in San Diego. We crossed the international date line three times in just 30 hours, effectively experiencing the longest Feb. 4 of anyone on the planet.

We assisted in repatriating more than 800 people, including 40 Canadians. During the flight, we had to be consular officers, Chinese-language translators, customs negotiators, baggage handlers, flight attendants and medical assistants. On landing in the United States, we entered quarantine for two weeks and were grateful for the time to catch up on sleep.

Interestingly, of the 10 consular officers on the Wuhan rescue mission, four were from the 196th A-100 and on first tours as consular officers in China. We had been assigned to Mission China and had all gone through the uniquely intense life that is learning Chinese at the Foreign Service Institute.

On arriving in Seoul, I knew the mission would be successful because those in my cohort had also leapt at the opportunity to go into Wuhan. I knew if I were going to fly into a pandemic to rescue Americans, I would want to do it with fellow members of the “Unlikely” 196th A-100 (so named for starting in late 2018 following the end of the hiring freeze).

My husband and I took this picture of ourselves [above] after a fit of laughter over getting on a plane mid-mission without knowing to what country we were flying.

Been Here Before

Gary Gray

Washington State

Among the many abandoned animals wandering around Dili in the wake of the September 1999 destruction of the city were these horses grazing outside the U.S. mission and residence. At the time, Presidential Management Intern Erik Rye, standing at back, was the only mission staff member other than the author.

Gary Gray

As my wife and I stroll through the idyllic Fort Vancouver National Historic Reserve near our home in Southwest Washington state, I find myself instinctively going into 360-degree mode, constantly looking around and behind me.

But now, during the COVID-19 pandemic, instead of watching out for Maputo bandidos, Securitate and KGB surveillants in Cold War–era Bucharest or Moscow or, more recently, rapacious soldiers in Juba, my eyes are peeled for runners, cyclists and skateboarders who could come upon us suddenly, violating the six-foot distancing rule.

I’m struck by how familiar the current circumstances seem, by how reminiscent they are of my previous Foreign Service and United Nations peacekeeping lives. Reading all the accounts of wildlife appearing on now-deserted city streets, I can’t help but recall our first months in 2000, setting up the U.S. mission in devastated Dili, Timor-Leste, when liberated animals were everywhere.

Goats, hogs and cute piglets were frequently underfoot, inducing my wife to swear off pork forever. We gave water to a group of emancipated horses grazing on the grass in front of our office/residence. From among the hundreds of canines wandering around, we adopted a bedraggled puppy who would become the unofficial U.S. mission dog.

In the first anxious weeks of Washington state’s lockdown, as we delved into the inner reaches of our pantry for some well-past-the-sell-by-date peanut butter and beans, I felt fortunate to have overcome any qualms about consuming expired food while serving in Bucharest and Moscow. There, in the 1980s, our embassy shops featured a variety of expired jars and cans discarded by U.S. military commissaries in West Germany.

The challenge of filling the hours when our usual leisure activities no longer exist evokes a long 1992 temporary duty (TDY) posting to help set up the U.S. embassy in Minsk, then still very much a Soviet provincial town offering few diversions outside work hours. Anticipating this issue, I brought along my long-neglected copy of War and Peace, finished it in two weeks, and remember feeling rather disappointed that the book wasn’t longer.

Dealing with disease threats is also all too familiar. Seeking some context, it’s been interesting to look at the relative degrees of lethality of the more serious maladies my wife and I contracted during our Foreign Service years, including dengue, chikungunya and Shigella, to name just a few.

Without doubt, we FSOs and ex-FSOs may be among the best prepared for the current challenges. But I’m finding that the template for assessing hazards that I employed in places like Timor, Indonesia and Mozambique—that the risks be clearly defined and reasonably low, and the objectives worthwhile—is not quite working in this present situation.

This is more like being in South Sudan in 2013, dispatching people on fact-finding missions to isolated locales with only the scantest, mostly outdated intelligence on which amorphous murderous armed groups may be operating in those areas.

A military colleague commented then that it was the worst situation he had ever seen; at least in his previous experience in Iraq and Afghanistan, there was a systematic method of assigning a quantified risk score to every sector.

Most frustrating of all in this present situation is the unknowingness—not being able to define the risks of entering the potentially perilous supermarket (are the odds of infection one in a thousand, one in a hundred?), realizing all the while that our Foreign Service friends throughout the world must be confronting such uncertainties many times over.

Embassy Juba Mobilizes

Eric Wright

South Sudan

Thirty-six U.S. citizens and six U.S. legal permanent residents board an Ethiopian Airlines flight at Juba International Airport on April 10.

Eric Wright

South Sudan had plenty on its plate before the pandemic. Burdened by years of conflict, its people were focused on their new transitional government, the training of unified security forces and the slow progress of their peace process. The emergence of COVID-19 has threatened these gains, as well as the livelihoods of a vulnerable population.

The entire Embassy Juba team has mobilized to assist the people of South Sudan, the transitional government and, most important, American citizens. To illustrate the extent to which ours is a whole-of-government effort, I’d like to introduce you to three members of the Embassy Juba Country Team.

Tina Yu is the lead for USAID’s Disaster Assistance Response Team (known as DART). Once during training at the Foreign Service Institute, a guest speaker from USAID explained that the agency harbored a few distinct workplace cultures, including some employees who are “cowboys.” I learned what that meant when I met Tina.

At 5:30 a.m., you can find her scrutinizing printed copies of emails while going all out on the treadmill. As for the rest of the day, she never slows down from that running start. She is a tenacious defender of humanitarian access and assistance to vulnerable populations.

For example, the U.S. government just approved $13.1 million to address COVID-19 in South Sudan, supplementing the hundreds of millions of dollars in life-saving assistance we contribute to the country every year. The unmatched passion, attention to detail and urgency Tina brings to her work ensures that that money has the greatest possible effect.

Dr. Sudhir Bunga has been the country director for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at Embassy Juba since September 2017. He and an interagency team manage the President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) program, as well as supporting Ebola preparedness in South Sudan. As the COVID-19 epidemic grew into a pandemic, he quickly pivoted to this new threat.

One of the most knowledgeable people I have met, Dr. Bunga has brought badly needed epidemiological expertise to the COVID-19 response in South Sudan. He has given presentations and recommendations directly to the government’s high-level task force, including First Vice President Riek Machar. He has the offices of key decision-makers on speed dial.

Always rational, with data on hand to prove his points, Dr. Bunga has helped to inform the decisions of both South Sudan’s government and the Embassy Juba Country Team. He also has to be the calmest person ever to stare down a pandemic.

Master Sergeant Kevin Hanly, normally the Defense Attaché Office’s operations coordinator, has been acting defense attaché since January. Proof that a knack for diplomacy is an integral trait for our Department of Defense colleagues, MSG Hanly has been a crucial link to decision-makers at Juba International Airport. When he rolls up to the airport in his aviator sunglasses, he is warmly welcomed by the military, intelligence and civil aviation officers who wield veto power over every flight.

The credibility that MSG Hanly brings and the strong relationships in which he’s invested have resulted in the approval of weekly special commercial flights. These flights are the only semi-reliable option out of the country. As a bonus, these commercial flights have allowed us to avoid requesting a charter flight at a time when finite resources are stretched so thin worldwide.

This is a whole-of-government effort for every embassy around the world and every federal agency back home. There is no greater calling than helping fellow citizens in need.

As of early May in Juba, repatriation flights organized by our embassy team had carried 101 American citizens and eight legal permanent residents home to the United States. Our small consular section had also processed 31 repatriation loans worth $89,741, enabling destitute Americans to return to their loved ones amid the pandemic.

There have been some long days and nights, but the effort is well worth it every time we wave across the airport tarmac at Americans walking toward the plane taking them home. When they wave back, most will never realize the diplomacy needed to get that plane into Juba. But the mission is rewarding, especially when your embassy colleagues are as outstanding as the team we have in Juba.

Foreign Service Kids Show Resilience

Kelly Cotton

Washington, D.C.

The Cotton family.

Courtesy of Kelly Cotton

As a tandem couple, my political officer husband and I, an office management specialist, have each experienced exciting careers for more than 15 years—most of that time with two kids in tow. From posts such as Nairobi, where transnational terrorism was a daily reality, to Dhaka, where freedom of movement consisted of a four-mile radius, ask the Cottons; most likely, we have either experienced it ourselves or know someone who has.

Yet many do not stop to think about the ideas and thoughts of the Foreign Service children who are along for this ride. We tend to try to soften the blow or keep the fairy-tale life going, not realizing how resilient they really are. Take our children, 14-year-old Zinzi and 15-year-old Zora, as examples. They have been out of the United States pretty much their entire lives, and can hold an impressive conversation about the importance of understanding host-country cultures.

Around age 9, however, Zinzi began complaining about the constant changes associated with our lifestyle, including losing friends with every permanent change of station. Realizing that the Cotton kids had never had a genuine American experience beyond an R&R, we decided to bid on tours in the United States and have been in Washington, D.C., for the last three years.

With all the hardship, disease, danger and other unexpected life events we have ducked and dodged as a family overseas, who would have ever thought we would be facing an invisible death threat called COVID-19 at “home,” in the land of “the beautiful and the free”?

Surprisingly, Zinzi and Zora did not react as one might expect. Neither blinked an eye when we told them that schools were closing across the nation for the remainder of the year, including their own. In the same breath of acknowledging they would miss their friends, they asked about next steps.

After we truthfully answered their questions about the coronavirus, they both went into Foreign Service mode and developed a plan. Monday through Friday, in the morning, they would have breakfast and get started with school assignments. After school, they would complete chores, and then have relaxation time and activities of their choosing. Once online schooling had been established, they immediately got connected, participated in virtual school meetings and got down to business.

They have adjusted better than one would expect from adolescents. For instance, Zora asked if she could attend a friend’s birthday party. When we asked her about social distancing, she explained that the birthday party would be virtual. She even made a birthday banner and baked a small cake to “eat” with the rest of the kids. They all sang songs, ate their respective cakes, played games—and two hours later, she couldn’t stop talking about all the fun she’d had.

Realizing that Foreign Service children are used to change just like we are as officers and specialists is the first step in creating a stable environment during uncertainty. From our experience, they are often willing to go with the flow and take on unforeseen challenges with the hope for a brighter future.

Under stressful circumstances, we must also challenge our children to act as leaders and team players by encouraging them to bring forth and share their unique talents, which can be as simple as singing for the family to help keep spirits up, or baking a cake for a friend in need of a birthday celebration.

As we have seen (in this situation and others), Foreign Service life can build brave and resilient children.

A Small Post in Action

Jean Monfort

Conakry

Embassy Conakry’s team after completion of the evacuation flight. More than 120 American citizens were successfully evacuated from Guinea.

U.S. Embassy Conakry / Kenya James

A young passenger waits to check in with her family for the Conakry evacuation flight in April.

U.S. Embassy Conakry / Kenya James

Conakry is a small post, so when COVID-19 hit and the airport shut down, the whole mission came together to help get American citizens home. I was pulled from the Regional Security Office to work on the consular team. As the embassy started drawing down and going to shifts (which would eventually turn to full telework), we were using new technologies and coordinating over new telework platforms, with no time to waste being confused or unsure.

Our acting defense attaché reached out to the Guinean government on airport procedures, the general services officer (GSO) coordinated with airlines, and the regional security officer (RSO) worked on getting airport security in place. The embassy was a hive of activity.

Promises of breathing room evaporated as Ethiopian Airlines first delayed the evacuation flight arrival, and then pushed the arrival date up. Our consular section stayed in constant contact with American citizens to keep the shifting information from becoming overwhelming. The last days before the flight took off were long ones, and the stress was palpable. Lists were checked and rechecked. The government-imposed curfew loomed in the evening hours as we applied labels and verified passport numbers and phoned passengers, so they knew to be at the airport.

We handled the joyful, the frightened and, oddly enough, the indifferent. When hard decisions had to be made (How many attempts to reach a person before moving down the list? Should we reopen a previously closed file, just in case?), we made them and supported one another. And when things got tangled, we gave one another space to be frustrated. That was key, I think—we never forced teammates to ignore their emotions. We had confidence that the task would get done, and it did.

At the airport, the line was long; many showed up early. We had designed a flow chart, with stations and measures to prevent clustering (for passengers’ health). We set clear guidelines with the airline representatives. From the GSO to RSO to Facilities, basically any office that could spare someone to help did so, setting up copiers, cordoning off sections of the terminal and coordinating with the tarmac crew. Ambassador Simon Henshaw walked the entire line, stopping to speak with just about every passenger.

It was impressive to see it all come together in a short time, in a courteous and professional way. We had to alternate between French and English, and when there were miscommunications, no one got upset or combative. Everything was handled with—and forgive me for being on the nose—diplomacy. Those who were not allowed on the flight were treated with grace by the processing station, then by consular officers and finally by the RSO team. Never once, from when we started processing passengers to when the last passenger tearfully turned and went back to the city (unable to “abandon” her life), did our team falter.

I am profoundly proud of the work we did that day. Our small team at our small post successfully sent more than 120 passengers out on one of the last flights leaving Conakry.

Each office brought something to the effort, and that sort of camaraderie really affected me. This is my first tour. If the State Department is capable of achieving this kind of work, then I know I’ve chosen the right profession.

A Different Kind of Crisis

William Bent

San Salvador

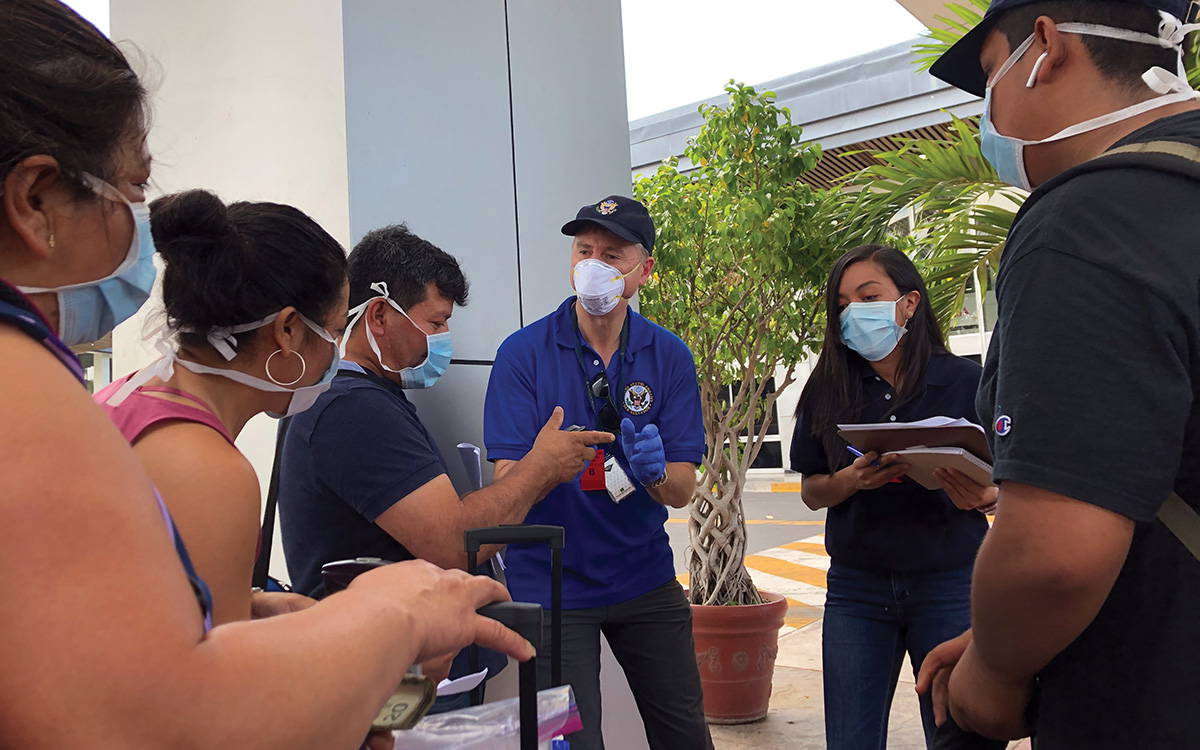

Acting Consul General Bill Bent and Locally Employed Staff Member Ingrid Hernandez assist U.S. citizens at El Salvador International Airport in March.

U.S. Embassy San Salvador / Claire Dennis

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, the government of El Salvador took extraordinary steps to contain the virus, including banning the entry of foreigners, closing the airport and implementing a monthlong stay-at-home order. As you can imagine, these measures significantly affected U.S. citizens in the country, many of whom found themselves stranded because of the airport closure.

As events unfolded, the consular section faced numerous difficulties attempting to respond to requests for assistance while contending with our own staffing shortages as a result of the host country’s quarantine and our effort to maintain social distancing.

I am proud of how U.S. Embassy San Salvador responded to these challenges. As of this writing in late May, we have repatriated more than 7,000 U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents without, I should add, the availability of U.S. government– funded charters.

It was truly an all-embassy effort:

- The political section obtained flight clearances for commercial repatriation flights.

- Department of Homeland Security/ICE officials allowed us to use their aircraft.

- Management section staff helped us with transportation and other logistics.

- Public affairs section staff helped ensure that U.S. citizens were informed of their options.

One of our vice consuls, while assisting our citizens at the airport during the crisis, told me that this was the most rewarding experience of her life. I could not agree more: It is an honor to serve the American people in their time of need.

The crisis led to amazing cooperation and sharing of best practices between posts. As leader of the San Salvador consular team, I depended heavily on the advice of colleagues in Guatemala and Honduras, who were dealing with similar challenges in repatriating U.S. citizens. Meanwhile, we were developing our own best practices, which I was able to share with colleagues as far away as India and Ghana via WhatsApp and other social media platforms.

One of our stellar Locally Employed staff members, Ingrid Hernandez, developed a web forms–based method to gather information from U.S. citizens seeking assistance; it saved hundreds of hours of labor and significantly reduced what had become an overwhelming number of phone calls. The Bureau of Consular Affairs then adopted our innovation and, after a slight modification, pushed it out to the field as a best practice.

This isn’t my first go-around assisting U.S. citizens during a crisis. In 2006, I traveled to Turkey where my consular colleagues and I facilitated the evacuation of Americans fleeing military action in Lebanon. In 2010 I helped lead an effort in the Dominican Republic to evacuate U.S. citizens from Haiti after the earthquake struck.

More recently, I coordinated U.S. Embassy Bridgetown’s consular response during the 2017 hurricane crisis, when thousands of U.S. citizens sought evacuation after three hurricanes in quick succession cut a destructive swath through the Eastern Caribbean.

But this crisis is different, both because of its global impact and because of the way it affects us all individually. I am here, as are many of my colleagues, serving in a country with limited capacity to respond effectively to a major health crisis or offer proper medical care should one of us fall ill. Separated from family and friends who are in the United States, I worry about their safety, too.

I nevertheless remain more determined than ever to stay here, serving the American people as a U.S. Foreign Service officer. This is what I signed up for.

Corona Haikus

Sylbeth Kennedy

Shenyang

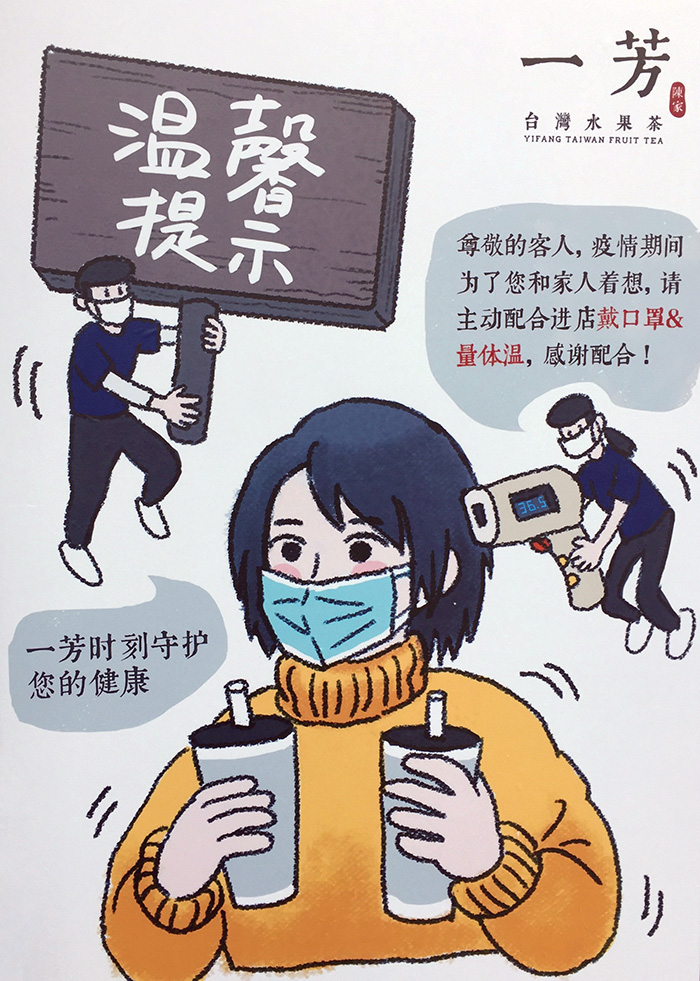

“We’re thinking of you at this time”—a sign with safety measures workers and customers must follow at a tea shop.

Sylbeth Kennedy

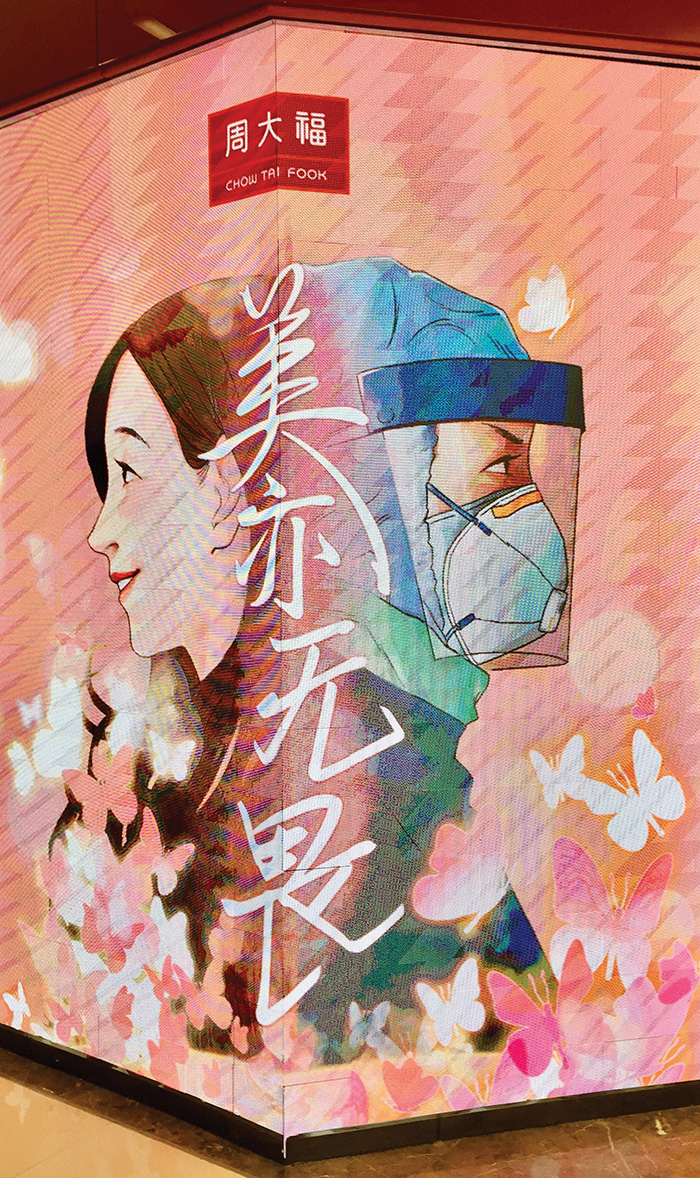

In front of a jewelry store, this ad says “Beauty has no fear,” or as the author calls it, “Love in the Time of Corona.”

Sylbeth Kennedy

’Bye, last month’s issues!

There’s a new virus in town

Bringing us all down

A zombie movie

A sense of dread in the air

Where’s everybody?

It’s a whole new world

One filled with fear and panic

I don’t like the news

There’s tunnel vision

Thinking only viruses

And not other things

I wish the fireworks’

Loud noises and bright colors

Could fight the virus

It is spreading fast

Along with the ignorance

Neither fight easy

Social distancing

Not for the shy anymore!

It’s doctor-approved

Masks for everyone

But not fun Halloween ones

This is scarier

The unmasked people

Shock me with their nakedness

Feels too intimate

Unmasked elderly

Have lived through horrible times

No virus scares them

My tones are bu hao

And speaking through my cloth mask

Ain’t helping a bit

Watching TV ads

Seeing what was filmed before

People with people

Nothing seems to change

Days blend into each other

I feel I’m drifting

My Shenyang? Spit globs

And scooters on the sidewalk

I miss it all now

Fit February

Was off to a horrid start

But it’s not my fault

Is it wrong to think

About cheap tickets, hotels

Once it all calms down?

It is all too much

I want to play ostrich

And ignore the news

We are home schooling

Supplies are non-essential?

The kids need paper!

My new work outfit

Is all about comfy pants

Leggings and PJs

Own your undyed hair

On trend is COVID color

Don’t cover grey roots

A blue-skied Shenyang

It’s an impossible dream!

Hope for the future

Spring is for rebirth

But now, all we hear is death

Bad seasonal start

Being resilient

Is taking care of yourself

While you’re freaking out

Welcome back, heroes!

Buses of doctors, nurses

Who helped in Wuhan

My happiest time

Was cheering for the returned

Combated COVID

The unseen people

Deep-fry cooks and janitors

Have become heroes

Find joy in small things

Clean air, working internet

Seek your happiness

So many hashtags

Alone Together, All In

These Uncertain Times

We are together

No matter where we live now

Always in our hearts

Putting Learning on the Air in South Sudan

Jeremiah Carew

Juba

In normal times, class sizes, especially in lower grades, number over 100 because students are eager to learn, and schools and teachers are scarce. This is a first-grade classroom at a school USAID is assisting in Rumbek, South Sudan, in October 2019. The adult to the right is the author’s counterpart at UNICEF who accompanied him on the trip.

Jeremiah Carew

On March 23, South Sudan’s school children joined a billion others around the world when the country’s ministry closed schools indefinitely to slow the spread of coronavirus.

South Sudan already had one of the weakest education systems in the world, with 72 percent of its children and youth not in school, according to a 2018 UNESCO report. Many obstacles explain that figure—from poverty and conflict, distance to school, untrained teachers and poor-quality education, to some parents’ beliefs that girls are more valuable for the cattle dowry they bring at marriage.

As USAID’s education officer in Juba and co-chair of the education donors group, I have been working with the ministry and donors to craft a response to COVID-19. While my USAID counterparts in many other countries are working on distance education using TV, smartphones or the internet, here the discussion is solely about radio distance learning. Even with radio, only 60 percent of the country is within range of an FM transmitter or has a radio in their home.

At the outset we wondered, what do we have to work with? We rediscovered a widely loved USAID-funded program from the early 2000s called “South Sudan Interactive Radio Instruction,” which many South Sudanese remembered from before independence in 2011.

We pulled apart an old radio for the memory card containing the audio files used in that program. We shared the files with another donor’s project that seemed ready to put the programs on the air, and then presented our plan to the ministry.

The ministry and a new minister were excited—about their own plan. Last year, they had launched a new curriculum and accompanying textbooks. They were concerned that children would be confused hearing lessons from the old radio program. They wanted teachers to record lessons from the new curriculum, yet they were starting from zero to develop their plan. It was going to be challenging, especially with all the restrictions on work and movement imposed by the pandemic.

This was the development professional’s classic dilemma: Does one support the direction of local actors or take a less risky, more technically sound approach? The question goes to the heart of our business and how we do our work.

In an April 2020 interview on NPR, then USAID Administrator Mark Green expressed strong opinions about USAID’s approach to development: “It’s listening carefully to our partner country leaders on the ways that we can respond to the needs that they identify. … We’re not transactional. We build relationships. We strengthen leadership, and we respond to those with identified needs.”

The donor community is highly aware of the cycle of aid dependency in South Sudan, and a frequently cited analysis shows that after each shock (e.g., drought, flood, locusts), the amount of assistance households required has increased. If our mission as an agency is “ending the need for foreign assistance” and facilitating a country’s “journey to self-reliance,” how do we do that in our day-to-day jobs? I wrestled with this dilemma and consulted my managers and other donors in figuring out our response.

As I write this, we have agreed to tightly coordinate with the ministry’s direction, offering ancillary assistance such as providing radios and taking surveys to see how many are listening and whether they are learning. We are nudging them to turn their ideas into implementation: workplans, budgets, task assignments.

We are suggesting that the old program, with its songs and counting games, might be helpful in bolstering the new content. And, perhaps most personally rewarding, I have built a relationship with my counterpart at the ministry. I’m on call via his WhatsApp for help and advice.

Another watchword from Mark Green’s tenure has stuck with me: “They have to want it more than we do.” The problem with ignoring local actors and dictating the solution is that the host country never owns that solution, meaning they will neither sustain it nor learn lessons from it.

My greatest aspiration for the work we are doing now is that because this vision was the ministry’s, it will turn into a sustained radio distance learning education program that the ministry leads after the COVID-19 crisis is over.

Work-Life Balance? Not a Chance

Christopher Merriman

Frankfurt

Two-year-old Charlotte plays with blocks while her father, FSO Chris Merriman, drafts an email on May 28 in Frankfurt, Germany.

Courtesy of Christopher Merriman

Work and life comingle in the Foreign Service. We’re told achieving the mythical “work-life balance” is key to longevity in this career. Months of lockdown during the pandemic, however, have obliterated my understanding of what that means. For me, adjusting to this crisis didn’t start to happen until I abandoned all preconceived notions about how to get through stressful circumstances.

When the stay-at-home order was issued, my wife and I were quick to focus on the potential advantages of the situation. We thought having two teleworking parents would give us the flexibility to cover child care for our 2- and 4-year-old daughters—at home once the preschool closed—and let us both thrive in our jobs. We’d been managing work-life balance in difficult situations for years, and we assumed we were ready for this new challenge. How wrong we were!

Efforts to categorize our time into “work” and “life” boxes quickly unraveled. How do you maintain balance when your office is also a child care center in a corner of your toddler’s bedroom?

Only thin walls separated the working parent from all the stomping, laughing, crying and yelling that two preschool-aged sisters generate when trapped inside together all day. Sometimes there wasn’t even a wall. The door would open, and one of the girls, desperate for some alone time, would sheepishly ask to come in. I knew we weren’t doing well when I heard my wife tell her, “Yes, you can play in your bedroom, but don’t talk to Daddy. He’s working.”

It was always painful to pretend not to be home—often impossible. There’s no way to stay out of the fray when one kid is having a meltdown and the other (the one working on potty training) doesn’t quite make it to the toilet in time. One ear is always stretching out into the apartment, sensitive to signs that the other adult has had enough and needs a break.

How do you maintain balance when your office is also a child care center in a corner of your toddler’s bedroom?

Similarly, keeping work out of one’s turn at child care was not feasible. As is apt to happen during a crisis, there were plenty of urgent emails and phone calls at all hours of the day and night. “Yes, I know I promised to play superheroes with you, but I have to talk on the phone with someone on the other side of the planet right now.”

Many in the mission have labored to make this less difficult for everyone. I’m especially thankful to my managers for strongly supporting a flexible schedule and to our community liaison office coordinator for fostering a virtual sense of community.

Similarly, we have remained immensely grateful that, so far, our extended family has been unaffected by both illness and job loss. We know that our experience with the pandemic has been easier than for many millions of families worldwide.

A pivotal moment in our path to acceptance, however, was realizing that “easier” doesn’t mean “easy.” Putting on a fake smile and thinking we should be happy that we didn’t have it worse only amplified our anxiety.

The stress started to lift when we gave up trying to achieve “balance” between being workers and being parents. My wife and I can take turns emphasizing one aspect or the other, but both work and life will remain inseparably mixed as long as the lockdown continues. Life is work, work is life, and we won’t be at our best at either until this crisis ends. Accepting that fact is what is getting us through.

Silver Linings in the Pandemic

Mariya Ilyas

Amman

Mariya llyas celebrates another successful round of consular efforts helping Americans board repatriation flights in Jordan with colleagues Olivia Sumpter (left) and Diana Madanat (right).

Mariya Ilyas

Consul General Bob Jachim oversees Embassy Amman’s consular reception station, which checks in Americans boarding buses to the airport for late-night repatriation flights.

Mariya Ilyas

When I was considering the U.S. Foreign Service, a mentor recommended I read Inside a U.S. Embassy: Diplomacy at Work (AFSA, 2011), a collection of narratives giving insight into the life and work of diplomats serving overseas. I read stories about the challenges of raising a family abroad, essays about pride and humility in serving our great nation, anecdotes of making friends from different cultures and expanding the concept of family and home, tales of travels in new and unfamiliar places—but the most poignant stories were diplomats’ reflections on responding to a crisis.

An immigrant from Pakistan, I started my dream career in September 2018. Yet never once during A-100 orientation or tradecraft training did it occur to me that I would be plunged into responding to a crisis myself during my very first tour.

Jordan was one of the first countries to implement a strict nationwide lockdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. On March 14, its government announced the closure of airports and borders, shut down the public and private sectors (except for essential services) and enforced a strict curfew that prohibited movement of people and vehicles.

The Jordanian government’s measures significantly helped contain the spread of the virus in a country of nearly 10 million people. The results speak for themselves: As of June 1, there were 739 positive cases and nine deaths.

When the health crisis became a global pandemic and airports shut down, U.S. citizens in Jordan began to panic. Emails and calls poured into the embassy, as people ran out of food, money, medication and—as the crisis dragged on—patience and hope. Our consular team worked long hours to log and respond to more than 4,000 inquiries. Some problems were harder to solve than others, but no plea for help went unnoticed.

While communicating with citizens and gathering data were the first steps in determining the need for repatriation assistance, the repatriation process had many moving parts and multiple stakeholders beyond the consular section. Embassy Amman successfully organized eight repatriation flights, helping more than 1,000 U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents reunite with families and loved ones back in the United States.

As an entry-level officer, I have found being a part of the COVID response team a professionally rewarding experience. Yet the long hours eventually led to physical and mental exhaustion. The curfew forced us to rely on grocery delivery services and enjoy the sunshine and fresh air only from our windows or balconies (if we were lucky to have one).

And while home confinement meant greater responsibility and heightened awareness for self-care, I found my health deteriorating. Exercise was no longer inherently built into my routine. Rather, I found myself hunched over my laptop, sometimes not leaving the couch for hours. I experienced a loss of appetite. The stress was compounded by a sense of loneliness as a single person in the Foreign Service.

As an entry-level officer, I have found being a part of the COVID response team a professionally rewarding experience. Yet the long hours eventually led to physical and mental exhaustion.

But Alhumdulillah, praise be to God, I am grateful for the support network at the embassy before these bad habits took a negative toll on my well-being. My supervisors supported flexible working hours, the deputy chief of mission frequently checked in with the first- and second-tour officers, the chargé d’affaires held town halls, the management section shared resources such as resilience workshops, and the Regional Medical Unit offered therapy consultations.

I took advantage of the counseling sessions and began to reconfigure my priorities by making time for hobbies such as reading and writing poetry. This alone time provided for space to pray, meditate, reflect and contemplate, luxuries in an otherwise hustle-and-bustle lifestyle.

We marked Ramadan, the holiest month in the Islamic calendar, a time for Muslims to fast and become closer to God, under strict social distancing rules. Ramadan is about community and charity, about selflessness and generosity. For the first time in my life, I broke my fast and ate iftar alone at the dining table each evening.

Recognizing that calamities can be a time for personal and spiritual growth, I found strength from communal reflection and prayer at the weekly “Halaqa Circles” that I hosted online. My faith keeps me going. I believe that while a dark cloud still lingers above us, and although we might not see it yet, there is a silver lining.

Getting the Job Done in Peru

Charles Sewall

Lima

USAID Officer Michelle Jennings assists a U.S. citizen preparing for his repatriation flight at U.S. Embassy Lima.

U.S. Embassy Lima

Chargé d’Affaires Denny Offutt stands by to greet as U.S. military personnel assist a passenger at the Grupo Ocho Peruvian Air Force Base in Callao (Lima).

U.S. Embassy Lima

When we started the workday on March 16, few of us in Embassy Lima fully grasped what was coming our way and the new roles we would be taking on. The night before, the president of Peru had implemented a state of emergency, instituting a strict nationwide lockdown, closing the borders, and halting air and land transportation—effective immediately.

The vast majority of our Locally Employed (LE) staff had no way to get to work in the morning. With some U.S. staff returning home on authorized departure in the following days, the greatly reduced U.S. Embassy Lima workforce quickly discovered a new challenge: repatriating thousands of our fellow citizens trapped across Peru.

It was in this context that I raised my hand for the role of mission volunteer coordinator, which gave me a unique window into the different responsibilities our people took on, and the impressive and enthusiastic way our community came together.

We had to invent a system that would transport thousands of Americans stranded across the country to Lima, conduct registration and administrative processing in the embassy parking lot, bus them to a restricted-access military air base, facilitate further screening by Peruvian officials and, finally, help them onto U.S. government–chartered aircraft.

It quickly became apparent that this would require more hands on deck. The answer was volunteers. We reached out across the whole mission, sorting volunteers by language skills, ability to physically get to the embassy and willingness to do public-facing jobs that would potentially expose them to thousands of people. Over 180 people signed up, and we matched their skills, situations and risk tolerance against the work required.

The more labor-intensive roles were crowd control, passenger screening and moving luggage, both at the embassy rally point and at the air base. We needed people who had a car with diplomatic plates for access through security checkpoints, and were willing to work with the public. Though this narrowed the field of candidates, more than 70 people stepped up for these jobs.

We set up three embassy-based teams (Condor, Jaguar and Llama), with each team working two out of three days. Drug Enforcement Administration agents, military personnel, Foreign Service officers, personal service contractors and eligible family members worked in the hot sun, wearing face masks and gloves, and doing heavy physical labor. At the air base, our military and consular colleagues and a few civilian staff ran a similar operation without rotational breaks.

Not all jobs were outside and public facing, but all were critical. Approximately 15 volunteers staffed a consular call center to guide Americans through the process and ensure they were ready to travel to avoid empty seats on buses and planes. On-call volunteer drivers supplemented our motor pool, which was nearly wiped out by state-of-emergency restrictions. Officers and LE staff from throughout the embassy—some by telework—supplemented management, consular, public affairs and the front office. We even had a volunteer social-distancing monitor.

The dedication and willingness to serve of so many members of our community were impressive. The embassy rally point operation team lead was a U.S. Marine Corps major who was in Peru as part of a one-year regional orientation program for foreign area officers. His specialty was combat logistician, so this role fit him like a glove. He kept the teams motivated and the buses running on time. Both he and his wife volunteered, and many other households had several family members participating.

The DEA regional director, responsible for all Southern Cone operations, was out there every day, along with his teenage daughters, moving luggage for elderly U.S. citizens. Two LE staff members from the Office of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement who could walk to the embassy took on leadership roles at the consular call center. One family member worked outside with the embassy rally point team and spent her days off working at the call center.

A DEA information technology officer provided technical support for public affairs section video messaging. An INL officer coordinated all the movement of intraregional and metropolitan Lima chartered buses and INL aircraft, moving more than 2,000 U.S. citizens from around the country to Lima.

When we needed folks to spend the night at the embassy to meet buses arriving before the government-mandated curfew, I didn’t think we would get anyone. But multiple volunteers came forward, more than we needed.

There are many more of these stories. In the end, Embassy Lima moved more than 8,000 U.S. citizens from across Peru to the United States over the four-week initial crisis period in an impressive demonstration of resilience and teamwork. People put their day jobs and their egos aside to get the job done. I am proud to have been part of it.

DS and MED Team Up

Stephen Donovan

Cabo Verde

In Cabo Verde at the makeshift secure storage/operations center. Left to right: Steve Donovan (DCS), Joseph Kazacos (DCS), Jared Strom (DCS), Laurean Pope (OPMED) and Casey Roberts (OPMED). Not pictured: Travis Wildy.

Courtesy of Stephen Donovan

Casey Roberts (at right, front) and the author under the wing of an aircraft during a torrential downpour in Monrovia.

Courtesy of Stephen Donovan

Although the COVID-19 pandemic initially had a limited impact on the Diplomatic Security Service’s Diplomatic Courier Service, we anticipated that something more widespread and hazardous might happen given the nature of the crisis. DCS reached out to our longtime partner in crisis management logistics, the Office of Operational Medicine, to determine if there were any mutual airlift needs or opportunities.

As it happened, OPMED had COVID-19 testing equipment and personal protective equipment (PPE) to deliver while we had a cache of mission-critical material to distribute. Together, we organized an ambitious plan to deliver material to more than 24 posts in West Africa and Europe using OPMED aircraft based out of Cabo Verde.

We also coordinated complex courier/OPMED itineraries for missions to East Africa, Asia and the Middle East based out of Diego Garcia, an island in the Indian Ocean, and service to South America based out of Miami. Overall, we delivered much-needed material to 77 posts around the world.

On arrival in Praia, Cabo Verde, our six-person team encountered our first hurdle when a Cabo Verdean colonel demanded that we leave the tarmac without our classified pouches—something a courier never does. Working in tandem, DCS and OPMED personnel convinced the colonel to allow the team to take possession of our material and to transfer our classified storage and operations center to the small conference room of a nearby hotel. After several shuttles with a police escort, we unloaded the vehicles and lugged the material up the stairs to the hotel that would serve as our home for the next eight days.

U.S. Embassy Praia did an outstanding job preparing for our arrival and coordinating the necessary support to move between the hotel and the airport. We were grateful for their help, particularly as we were busy until 3 a.m. finalizing inventory, making arrangements for the next day’s flights and setting up a 24-hour classified pouch watch schedule. Amazingly, at 6 a.m. the next day, every member of the team was awake, alert and ready to go.

Each day, four team members were on the traveling detail—a courier and OPMED member on each of two separate aircraft—and would work a grueling 18-hour day, delivering medical equipment, PPE and mission-critical classified pouches throughout West Africa. One team member would maintain communications with posts receiving service that day, in addition to coordinating the itinerary and service for the following day. Nightly huddles in the improvised storage and operations center in Praia typically wrapped up late, with one team member, who drew the short straw, assigned the midnight-to-6-a.m. security shift to stand watch over the pouches. We all played every role, and the missions made for extremely long hours.

We began dispatching couriers and OPMED personnel on round-robin flights, servicing up to four posts per day and making adjustments on the fly. In one case, as our flight approached Niamey, Niger, we were waved off by the control tower who abruptly—and mistakenly—told us that we did not have landing clearance. With fuel running low, we had to change our course and head to our next destination and refuel. We then confirmed that U.S. Embassy Niamey had indeed secured permission to land before convincing the tired and reluctant flight crew to make another attempt.

Lessons were learned daily, and relationships were forged within the team. We worked together to solve not only DCS problems when issues were related to classified material but also OPMED concerns when the problem involved medical equipment or repatriation. Local officials grew more comfortable with us each day as we demonstrated a high level of professionalism and respect for the Cabo Verdean protocols put in place to ensure the safety of local staff.

The experience gained during this inaugural mission validated a road map for subsequent missions based out of Diego Garcia, Naval Support Activity Souda Bay, Boca Raton and Ramstein Air Base, facilitating the eventual support of more than 150 diplomatic posts worldwide.

The combined DCS/OPMED effort managing these colossal challenges saved lives, provided comfort and reassured our global diplomatic colleagues that they were not alone in a time of crisis. DCS and OPMED have worked together through several crisis situations in the past. But it appears the present collaboration, planned to continue for the next few months, feels like, as Humphrey Bogart puts it in the film Casablanca, “the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

Evacuees Shop Free

Ann La Porta

Washington, D.C.

Ashley Hayes, on evacuation from Mexico, “shopping” at the Junior League of Washington’s Tossed and Found.

Courtesy of Ann La Porta

When the State Department announced a global authorized departure for some posts and an ordered departure for others, families flooded into the Washington metropolitan area with suitcases in hand and toddlers in tow. Some traveled to their safe haven addresses since they could telework from anywhere, while others stayed locally, crammed into small, sparsely furnished apartments and forced to shelter in place along with everyone else in the region.

As chair of the Evacuee Support Network of the Associates of the American Foreign Service Worldwide, a volunteer organization that has been supporting foreign affairs families for 60 years, I was soon contacted by the Junior League of Washington. Their chief fundraising event, a huge rummage sale called Tossed and Found, had to be canceled because of the pandemic, and they were left with a giant warehouse filled with goods. The Junior League was offering access to these goods for free to foreign affairs families who had been evacuated.

All we had to do was find the customers, a task easier said than done. In February, our support network had been able to contact the China evacuees because some of our AAFSW members knew the community liaison office coordinators there. We had assisted about 30 families, but this was now a global undertaking, and we were unsure how to connect with evacuees in from other posts.

Fortunately, Jenny Kocher, who monitors our social media and is also co-chair of the AAFSW Foreign Born Spouse group, found a Facebook group dedicated to evacuees and those wishing to help. Bingo. We were in business.

Kelly Hunter, co-chair of Tossed and Found, daughter of State Department employees and granddaughter of an FSO, together with her very busy and dedicated committee welcomed more than 130 families into the Junior League’s Crystal City warehouse.

Although the warehouse has been packed up now, those families who “shopped” are eternally grateful.

Bikes and exercise equipment were in high demand. Kitchen supplies and gadgets flew off the shelves. Children’s toys, games, puzzles and books were almost depleted—anything to keep little ones occupied during isolation.

Although the warehouse has been packed up now, those families who “shopped” are eternally grateful. The AAFSW Evacuee Support Network has about 100 volunteers who stand ready to help more evacuees if they still have wish lists.

Karate for FS Kids

Alix Bryant

Gainesville, Virginia

Black belt world champion Hanshi Darren Cox with the author (right), also a black belt in karate.

Matthew Sauk

On March 30, when Governor Ralph Northam announced a stay-at-home order for Virginians, our kids had already been home for two weeks (Virginia was the second U.S. state to close its schools for the remainder of the school year). Our two boys were quick to provide “research” on the mental health benefits of playing video games on a daily basis, and our daughter petitioned us for access to the Houseparty app (we said yes) and to TikTok (nope, still too young for that).

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and more and more authorized departures were announced, I was prepared to help Foreign Service families cope with their new realities and adjust to their routines at home. I had already been homeschooling my kids until just this year, and had created a business around providing online resources for kids.

Karate has been a passion of mine since childhood, and the overwhelmingly positive response from parents made me happy to share this course with the young members of our community.

Since many FS families were struggling to find the balance between too much academic online learning and the alternative—too much screen time—I invited families to participate in an online karate program I had recently developed. More than 500 FS kids signed up within two weeks! Karate has been a passion of mine since childhood, and the overwhelmingly positive response from parents—most of them grateful for an outlet that allowed their kids to burn off a lot of pent-up energy—made me happy to share this course with the young members of our community.

I also gave away nearly 1,000 PDF copies of My Life as a Foreign Service Kid, an activity book I created for FS kids, with fill-in-the-blank pages to write about the places they’ve lived, their unique experiences, their favorite foreign foods and souvenirs, their goals and their dream destinations.

While I’m not on the front lines, as a Foreign Service family member I’ve been uniquely positioned to assist our FS community in my own way. By offering FS kids a creative outlet, families might see this time as a gift rather than a challenge.

Helping Americans Living Abroad

William Jordan

Paris

The author, at his computer in Paris, holds a virtual meeting with his Association of American Residents Overseas team to discuss the most recent Smart Traveler Enrollment Program (STEP) message from U.S. Embassy Paris.

Courtesy of William Jordan

On the morning of March 12, big news hit Paris, where I’ve lived since retiring from the Foreign Service in 2011. A few hours earlier, President Trump had announced from the Oval Office a ban on all travel to the United States from the European countries in the Schengen Area.

As France and other European Union states were still struggling to follow Italy’s lead in ordering lockdowns of the population, it was a bolt out of the blue, and stunning both in its lack of nuance and absence of detail.

A number of questions struck me: Were American citizens now banned from returning to their own country? When is this ban going into effect? Swirling in my head were visions of thousands of panicstricken tourists and long-standing residents in France streaming to the airports to get home, whatever the cost. (That is exactly what happened.)

During my Foreign Service career, I had been a political officer. My first assignment, however, was as a vice consul in Saudi Arabia, and it marked me indelibly, especially realizing that, almost every day and even in small ways, my actions could dramatically affect someone else’s life.

This same spirit led me two years ago to join the Association of Americans Resident Overseas, a nonprofit organization based in Paris that advocates on behalf of American citizens living abroad. With a paid membership of just over 1,000 in 41 countries, AARO focuses on taxation, voting and citizenship issues. On the board, I would serve as a liaison with the State Department regarding consular services.

I immediately queried the consul general in Paris as to what was going on. He responded that the president’s announcement had caught everyone by surprise, and that the embassy was still waiting for official instructions. Informally, however, he stressed that American citizens, legal permanent residents and their legal dependents would be allowed to travel to the United States. He asked me, as he would other American organizations in France, to spread the word through our respective channels.

With that mission, I contacted Christine Cathrine, AARO’s invaluable office manager, and Pam Combastet, AARO’s secretary and informal liaison to many of the other American organizations in Paris, and proposed that AARO set up a crisis communications task force. The task force would prepare and send out urgent messages to our members, asking them to share the information with other Americans, including visitors. We also urged those who had not done so to register with the State Department’s Smart Traveler Enrollment Program.

Per the “confinement” order in place throughout France, we hunkered down and adapted to operating virtually. AARO has sponsored webinars dealing with tax issues, like the implications of the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act. And we continue to send out “warden” messages, sharing information from the embassy and providing updated information on travel restrictions, the executive order suspending immigration visas, and the most recent caution to Americans overseas about how COVID-19 might affect their ability to vote by absentee ballot, to name a few. Emulating our consular colleagues, AARO members are Americans helping Americans abroad.

Retirees Spotlight Role of Diplomacy in Pandemic Response

Charles Ray

Washington, D.C.

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, our Foreign Service colleagues, at home and abroad, along with our Civil Service colleagues and foreign national staff, have demonstrated their value to U.S. national security time and time again. Retired members of the Foreign Service have also contributed to the effort in a number of ways, from writing op-eds to participating in symposiums to highlight what is being done now, and what needs to be done in the future to cope with such tragedies.

I have been working with Professor Yonah Alexander, director of the Inter-University Center for Terrorism Studies, on a project to highlight the role of diplomacy in the fight against terrorism and violent extremism for the past several years. When the pandemic put a crimp in face-to-face events, Prof. Alexander proposed we use our project to address the role diplomacy plays in crises of this nature. With the assistance of Professor Don Wallace, director of Georgetown University’s International Law Center, and his technical staff, we organized two symposiums via Zoom.

The first, “Combating Global Coronavirus: From Isolation to International Cooperation,” was held on March 26 and featured presentations by medical experts. My capstone presentation emphasized the need to increase international cooperation through diplomacy to deal with global crises, using the international response to the 2014 Ebola crisis as a model.

On April 14, we held a second symposium, “Combating Global Coronavirus: A Preliminary Assessment of Past Lessons and Future Outlook.” The presentations from medical experts included one from retired FSO Ambassador Jimmy Kolker, who served previously as assistant secretary for global affairs at the Department of Health and Human Services and chief of the HIV/AIDS office at UNICEF in New York. [See Kolker’s article here.]

Amb. Kolker and I stressed the need for creative, visionary leadership at the highest levels of American diplomacy to work our way out of the current crisis and prepare for the next one. We highlighted the heroic efforts of our Foreign Service and Civil Service colleagues under arduous conditions, and their dedication to duty despite not always receiving the support of our senior political leadership. Just another example of what the U.S. Foreign Service, active and retired, does to protect U.S. national security interests.

The symposiums can be viewed on YouTube at https://bit.ly/IsolationCooperation and https://bit.ly/PrelimAssessments.

Rip Van Winkle in Islamabad

Michael Nehrbass

Pakistan

Author Michael Nehrbass takes a selfie after his second COVID-19 test.

Michael Nehrbass

Michael Nehrbass and his cat, Boi, who are both healthy again.

Michael Nehrbass

Given Pakistan’s location and population, there was never a question of whether the country would be affected by the pandemic—only a question of when. Many COVID-19 cases in Pakistan are linked to Pakistanis returning from a pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia and Iran. Alas, at least one case stems from a diplomat.

In early March of this year, after a leadership conference in Washington, D.C., I was traveling back to Islamabad and stayed overnight in London. There, with the number of coronavirus cases on the rise, I tried to limit myself to roaming around Kensington Gardens. Inevitably, however, my desire for cask ale and Malaysian cuisine led to my downfall.

I returned to Islamabad on Friday, March 13, worried about work and our family cat, Boi, who had fallen deathly ill while I was away. I felt healthy but under pressure to get to work. International crises bring out the best in the U.S. government; USAID is no exception. Through interagency cooperation, USAID/Pakistan had managed to secure $1 million of health funding from supplemental COVID-19 resources and was making a case for more funding (as of early June, it was managing more than $20 million of COVID-19 response funds). U.S. Embassy Islamabad, while always very occupied, seemed exceptionally busy.

On Tuesday, March 17, my telephone rang. The health unit had learned of my stopover in London and placed me on self-quarantine. Suddenly, I found myself at home trying to set up telework, fuming at the inconvenience when there was so much work to be done at the office. At least I could get a local veterinarian to examine our cat, who began a regimen of medications.

When I reported a mild temperature to the health unit, a team in full protective gear came to test me. On Friday, March 20, I learned of the result: I had tested positive for the coronavirus.

Fortunately, because of the health unit’s quick work, my limited time at the embassy prevented the virus from spreading. Over the weekend, I told everyone that it felt like I had a mild cold. The health unit called me periodically to ask if I had any trouble breathing, which was disconcerting. By Monday, my temperature climbed to 102 degrees, and my muscles and joints ached. I felt weak and had no sense of taste; eating was a chore.

The reality of COVID-19 sank in when I became out of breath after walking upstairs slightly fast. I could no longer take a deep breath without coughing; my reduced lung capacity scared me. Now I had no qualms about being away from work—I felt useless. I looked like hell, and so did the cat.

My veterinarian had to go into quarantine. Before he did, he dropped off an alarming amount of injectable medicines. Amid my illness, I had to embrace distance medicine for felines by learning how to administer injections. I kept the cat company by taking my own array of medications. Time in quarantine passed slowly. Every day, I connected with my spouse in Takoma Park, Maryland, by video call, fielding numerous questions about the cat from my children.

The embassy’s circumstances changed quickly over the next two and a half weeks as American staff began to telework or leave on authorized departure. Most Pakistani employees went on administrative leave or began teleworking.

Finally, the cat and I recovered our health. After a second COVID-19 test on April 10, this time negative, I was free to go to the embassy. When I arrived, I felt like Rip Van Winkle, having awakened to a time far into the future. The compound seemed eerily empty as it operated with reduced personnel. A skeleton USAID staff continued to manage projects, contribute to embassy reporting and successfully obtain more COVID-19 supplemental funds.

I could no longer take a deep breath without coughing; my reduced lung capacity scared me. Now I had no qualms about being away from work—I felt useless. I looked like hell, and so did the cat.

Colleagues dressed more casually, and some had cut their own hair, as dry cleaners and the barber had both closed. We compared notes and commiserated over hardships while dealing with our families’ anguish at home. Like me, everyone seemed to know someone who had a canceled graduation ceremony, kids frustrated by the sudden transition to online classes, or friends and family hating the lockdown.

Disappointments and aggravations abound, but there is also hope. Now I am working again, enjoying our esprit de corps at post and supporting the COVID-19 response. I am grateful to the health unit, which enabled my recovery while protecting our embassy community.

Waiting for Takeoff

Stephanie Allen

Arlington, Virginia

Stephanie Allen working in temporary quarters in Arlington, Virginia.

Courtesy of Stephanie Allen

I was a newly hired diplomatic courier who had just finished training when the COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and change-of-station (PCS) hold began. My courier class, which was five strong, was excited and ready to start our careers, and then, almost overnight, we went from full steam ahead to full stop.

Having lived in Cambodia for many years, I was no stranger to “going with the flow.” What has struck me the most about this experience, however, is the feeling of isolation. Staying alone day after day in a temporary apartment—my fiancée and cats 8,000 miles away—has been a challenge. I miss them very much.

I have been combating this confinement with gratitude. I am thankful that I remain employed, that I have a safe place to weather the crisis, and that my older parents and brother are safe and healthy, as well.

Although my time here at the State Department has not really started yet, I know that when we all return to our roles we will be doing so in a changed world. I am grateful that I will be part of that effort.

I tell myself that staying healthy and being ready when called is my job right now. I often refer to the “United States Department of State Professional Ethos,” which I was given during my SOAR class (Specialist Orientation and Readiness; the 155th), and pay close attention to the line: “As a member of this team, I serve with unfailing professionalism in both my demeanor and my actions, even in the face of adversity.” Reading this ethos, particularly that line, gives me added purpose during this unusual time when I feel disconnected and less than useful.

Having lived in Cambodia for many years, I was no stranger to “going with the flow.” What has struck me the most about this experience, however, is the feeling of isolation.

The second weapon in my arsenal against the loneliness of quarantine is technology. The department’s quick pivot to telework has allowed me to keep the new information I have learned during my training (but haven’t had the opportunity to use yet) fresh in my mind. Technology has helped me stay connected to my family and my fellow couriers. My courier class has had a video chat facilitated by our operations officer in Washington, D.C., and not a day goes by that I don’t hear from colleagues.

It helps that my future post in Bangkok invited me to join in their video conference training, as well. This camaraderie really makes a difference and goes a long way in keeping a new hire, who’s stuck in limbo, feeling part of the team.

I know that at some point this stressful and tragic crisis will be behind us. I know that we all will be stronger on the other side of it. I hope to meet you during my eventual travels as a courier. Until then, stay safe and healthy, and I’ll see you out there soon.