Pearl Buck’s Rehabilitation in China

Reflections

BY BEATRICE CAMP

A portrait of Pearl S. Buck, circa 1932.

Library of Congress

Early in my assignment as consul general to Shanghai, I was invited to speak at the 70th anniversary of Pearl Buck receiving the Nobel Prize for literature. The conference took place in Zhenjiang, where Buck grew up with her missionary parents, Caroline and Absalom Sydenstricker.

Aware that Pearl Buck came from the type of missionary background that was denounced by the Chinese Communist Party, I was surprised by the invitation. During my first assignment in Beijing 25 years earlier, this kind of recognition would have been unthinkable.

I knew that Buck was not welcome in China for many years. Her request for a visa after President Richard Nixon’s historic 1972 trip was denied on the grounds, as stated in the rejection note, that her works took “an attitude of distortion, smear and vilification towards the people of new China and its leaders.” After her departure in 1934, Buck never again set foot in China.

As historian Jonathan Spence wrote in 2010 in the New York Review of Books: “Her views were not welcome in China: both Chinese nationalist politicians and intellectuals and the Communist forces dug in against the nationalists in the northwest of China objected violently to her vision of their country as backward, dirty, and demoralized. (The Chinese delegates invited to attend the 1938 Nobel celebrations boycotted the proceedings.)”

Declared a cultural landmark, the author’s former residence in Zhenjiang became the Pearl S. Buck Museum in 1992 after its restoration funded by the Chinese and American governments. Here is a room with Buck’s typewriter and portrait in the Zhenjiang museum.

Courtesy of Bea Camp

Buck lived in Zhenjiang, a city in Jiangsu province, until she was 18. The city at that time was a bustling treaty port at the junction of the Yangtze River and the Grand Canal, with a British concession. Zhenjiang is still one of China’s busiest ports for domestic commerce and famous for its black vinegar, which I learned to praise at every banquet during my visit there.

By 2008, more than 30 years after her death, Pearl Buck was back in favor in China, where she was now highly regarded—as a bridge between cultures and, possibly, a way to attract tourists. Zhenjiang embraced its long-ago resident as Buck moved from persona non grata during the Mao years to rehabilitated celebrity in the 21st century.

Meanwhile, Americans had lost interest, with many scorning Buck’s mass-market appeal. Spence quotes literary historian Peter Conn’s observation: “Pearl’s Asian subjects, her prose style, her gender, and her tremendous popularity offended virtually every one of the constituencies that divided up the literary 1930s. Marxists, Agrarians, Chicago journalists, New York intellectuals, literary nationalists and New Humanists had little enough in common, but they could all agree that Pearl Buck had no place in any of their creeds and canons.”

The façade of Buck’s former residence turned museum in Zhenjiang.

Wikimedia

It didn’t help that Hollywood had cast the movie version of The Good Earth in yellow face, passing over Chinese American actress Anna May Wong in favor of German-born Luise Rainer, who won an Oscar for the 1937 role. But, many years later, the Chinese academics at the conference craved reassurance that Pearl Buck was still important in the U.S.

My speech-prep research included asking my teenage niece, herself adopted from China, whether she had heard of The Good Earth; Buck’s novel about struggling peasants in China is her best-known book and cited in her Nobel Prize. I decided to take her vague response as a yes, allowing me to assure my listeners that the book was on school reading lists in the United States. That message was well received.

Pearl Buck’s hometown for childhood and early adulthood, Zhenjiang, had started actively promoting the author’s legacy, renaming its public park Pearl Square and unveiling a monument at the Zhenjiang No. 2 high school where Buck studied and later taught. A newly opened museum showed Buck studying the Chinese classics and called her a “daughter of Zhenjiang.”

The October 2008 conference attracted 100 participants, including several Buck family members from the United States and the board and executive staff of Pearl S. Buck International, the charitable organization in Pennsylvania. At the conference, agronomist John Lossing Buck, the son of the author’s first husband, gave further testimony to renewed interest from China in the once-scorned Bucks; he described a surge in Chinese contacts about his father’s research and historical land survey data, recently rediscovered at Nanjing Agricultural University.

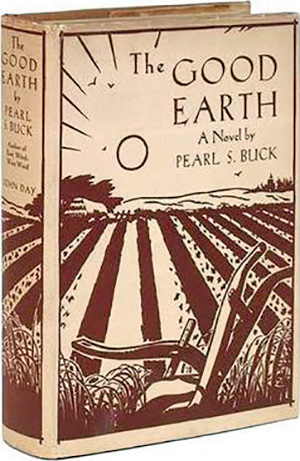

The first edition cover of Buck’s 1931 classic novel.

Between the Covers / Wikimedia

For those of us at the Shanghai consulate, the conference and related opening of a Pearl S. Buck Museum next to the restored family home offered an encouraging signal of strong interest in this U.S. connection. Looking ahead to the then-upcoming celebrations of the 30th anniversary of U.S.-China relations, we took Zhenjiang’s fervor for its long-ago American “daughter” as a good sign for the relationship.

Four years later, Pearl Buck’s image in China received another boost when Nanjing University gained approval for the restoration of the campus house in which Buck lived with her husband, who created and headed the university’s department of agricultural economics. Another site, the cottage at the missionary retreat on Lushan, where Buck and her family spent some of their summers, also became a tourist attraction, featuring a mannequin of Buck at a desk.

Whether these efforts represented an acceptance of Buck’s portrayal of China or an opportunity to capitalize on potential tourist interest, her rehabilitation was well on the way.

While remaining homesick for China throughout her life and heartbroken at being unable to return, Pearl Buck at least achieved a second life in the country that inspired her work and won her a Nobel Prize.