Making Our Rhetoric Real: U.S. Diplomacy in the Pacific Islands

The “Blue Continent,” historically viewed as a backwater of U.S. diplomacy, has become the scene of a new great power contest.

BY JOHN HENNESSEY-NILAND

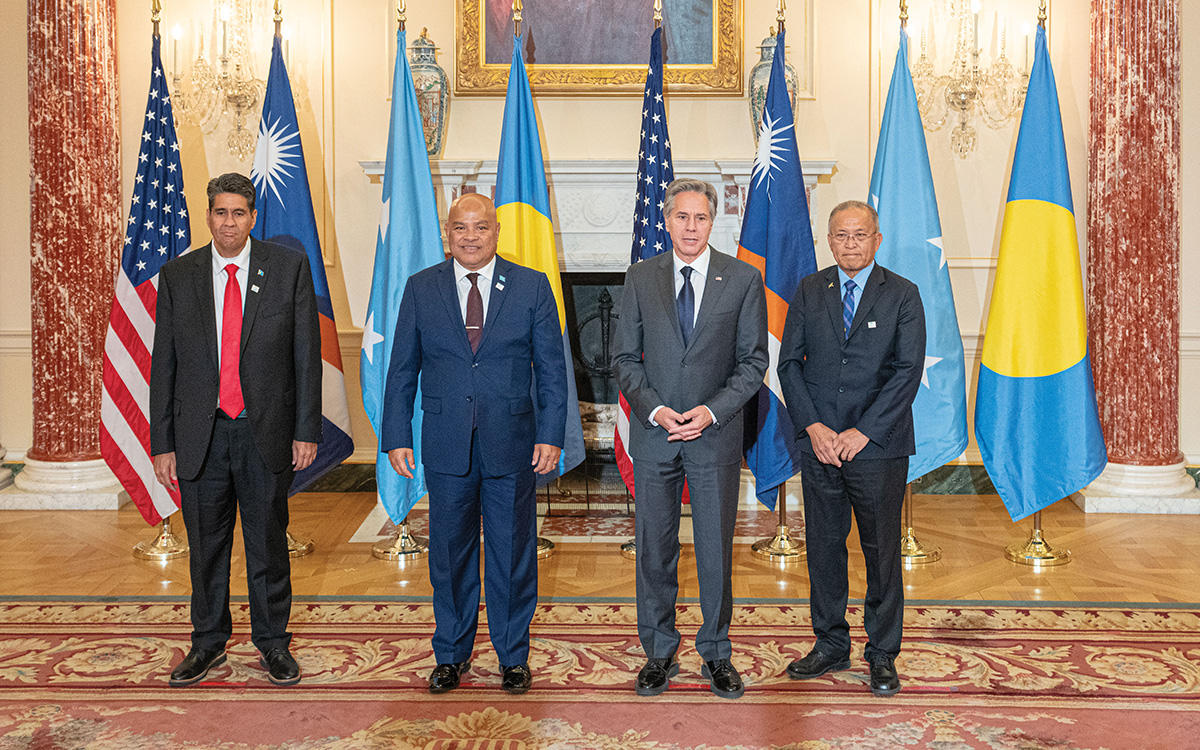

At the U.S.-Pacific Island Country Summit in September 2022, Secretary of State Antony Blinken (second from right) meets with (from left) President of the Republic of Palau Surangel Whipps Jr., President of the Federated States of Micronesia David Panuelo, and President of the Republic of the Marshall Islands David Kabua at the State Department in Washington, D.C.

U.S. Department of State

As the former U.S. ambassador to the Republic of Palau, let me be the first to admit that I have a bias. I believe that “the security of America, quite frankly, and the world depends on the security of the Pacific Islands.”

This was President Joe Biden’s statement at the U.S.-Pacific Island Country Summit in September 2022, where the president unveiled the first-ever “Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States.” One has only to look at a map or know a little about history, particularly World War II in the Pacific, to appreciate the strategic importance of these islands.

America’s official diplomatic footprint in the Pacific Islands dates largely to the conclusion of WWII. Today, more than 60 percent of global maritime trade transits the Indo-Pacific, much of it passing through the exclusive economic zones (EEZ) of Pacific Island countries. This region matters, always has, and will continue to do so.

Yet, despite this understanding and some questionable claims in the “Indo-Pacific Strategy” document, U.S. attention and engagement with the region has, in fact, waxed and waned over the decades. Administrations over the years have issued numerous policy documents and periodically stated that the U.S. “is back,” and that America has “pivoted” to the Indo-Pacific (again)—so much so that some commentators have asked, “When does a pivot become a pirouette?”

What is indisputable today, however, is that the Pacific Islands, at the center of the global maritime crossroads connecting America with Asia, are increasingly the scene of a new great power contest. And the challenge for America’s diplomats in our small and remote island posts there is to make our rhetoric real regarding U.S. interests in the region.

At the ribbon cutting ceremony for U.S. Embassy Koror’s solar energy project on April 12, 2022, from left: U.S. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, Ambassador John Hennessey-Niland, Special Presidential Envoy for Climate Secretary John Kerry, Palau President Surangel Whipps Jr., and Paramount Chief Reklai Raphael Bao Ngirmang.

U.S. Embassy Koror

The “Blue Continent”

The small-island nations that make up the vast geographic area of the Pacific Islands are sometimes called the Blue Continent. The EEZs of just three island nations—the “Freely Associated States” of Republic of Palau, Federated States of Micronesia, and Republic of the Marshall Islands (FAS)—are equivalent to more than half the size of the continental United States. But they have largely been viewed as a backwater for U.S. diplomacy, at least until recently. Official U.S. presence has been limited, with U.S. policy often considered one of benign neglect. Indeed, the view from the region was summed up in 2022 by then–Acting Prime Minister Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum: “Fiji and our small-state neighbors have felt at times, to borrow an American term, like a flyover country. Small dots spotted from plane windows of leaders en route to meetings where they spoke about us, rather than with us, if they spoke of us at all.”

At the policy level, the belated approval and funding by Congress of $7.1 billion in March 2024 for the next 20 years of the Compacts of Free Association (COFA) with Palau, Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands was critical. Although these are agreements with sovereign nations, it is the U.S. Department of the Interior that will continue to manage the bulk of the funding to support basic public services in the three countries in areas such as health, education, and infrastructure, while bolstering the management and oversight of Compact trust funds previously established for each of the states. Congress also included $634 million over the next 20 years to ensure continued provision of U.S. Postal Service to the FAS, a key link between the U.S. and these islands even in this era of email and messaging apps.

Our partners in the Pacific viewed the congressional negotiations on COFA as a litmus test of U.S. credibility and commitment. They see the success as a basis for further engagement and expansion of U.S. ties, not the limit of this relationship. Extension of benefits for the first time to veterans of the U.S. military in their home islands (something we worked very hard on while in Palau) and access to new health and education programs to citizens of the three states are so important and very welcome.

In addition to the Biden administration’s hosting of two U.S.-Pacific Island Country Summits in Washington, D.C., announcement of the opening of new U.S. embassies in the region also signals a renewed commitment. New posts in the Solomon Islands and Tonga opened in 2023; a new embassy in Vanuatu is planned for later this year; and discussions continue with Kiribati regarding a U.S. diplomatic presence there sometime in the future.

The Peace Corps is coming back to the region as well. Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga again have Peace Corps volunteers; Vanuatu will have volunteers later this year, and Palau will see their return in 2025. USAID is also expanding its presence across the region, as are other U.S. agencies and departments. These are important steps.

U.S. veterans and Gold Star families gather in Palau, Nov. 11, 2021. Ambassador Hennessey-Niland is third from left.

U.S. Embassy Koror

Making Rhetoric Real

It is important to acknowledge, however, that while the COFA agreements are a huge step forward, many of the other announcements and plans for increasing U.S. engagement in the Pacific Islands remain contingent on additional funding. As Bill Burns wrote in the March/April 2024 edition of Foreign Affairs: “Priorities aren’t real unless budgets reflect them.” Leaders in the Pacific have observed that despite pledges of more than $8 billion in U.S. assistance since 2022, much of this funding has still not arrived in the region. As I have written elsewhere, U.S. overpromising and underdelivering is a real risk to American credibility in the Pacific.

Our newly announced embassies in the region, for now at least and for the foreseeable future, are not full-service posts. For example, these tiny posts, staffed with one or two officers on temporary duty, are not equipped currently to provide the consular services that are so important to Americans and host-country nationals alike in these distant and remote locations. Rather, they are small, micro posts, similar to “Presence Posts” that were established in other parts of the world in past years. Filling these few positions has proven difficult because these jobs have not been seen (with some justification) as career enhancing, even if they can be career enriching.

While these posts are not high threat in terms of the potential for terrorism or violence, this is somewhat misleading because rising crime is a concern even in the islands. A number of these countries have experienced political unrest. Further, access to health services and education and opportunities for spousal employment can be limited at the small island posts. Even our embassies in the Pacific are undersized, though they do now have more staff, interagency presence in the country teams, and additional new resources.

Many of the other announcements and plans for increasing U.S. engagement in the Pacific Islands remain contingent on additional funding.

Still, the discrepancies with larger U.S. missions in the Indo-Pacific can add to the perception that the Pacific Islands do not matter as much to the U.S. government. These real or perceived “slights” can be significant in a region where there is competition for allegiance and to be the partner of choice. The islands are located far from Washington, but they follow closely what is happening in our government. They pay attention to budget discussions and inside-the-Beltway policy machinations and issues like appointments and staffing charts. These governments have noticed that while there used to be a director at the National Security Council solely responsible for Oceania, as well as a deputy secretary of State responsible for Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands, both roles are now subsumed in larger portfolios.

These changes are seen as inconsistent with U.S. claims of an increased focus on the region, even though the U.S. has also established a new envoy position to the Pacific Islands Forum. I think it is fair to acknowledge that some of our challenges in the region are in part a result of our bureaucratic approach and policy “own goals,” as our Australian friends would say, but this only heightens the challenges.

So how can we make our rhetoric real in the Pacific? I have served multiple tours in various positions at our embassies in Palau, Australia, and Fiji, and as the foreign policy adviser with the U.S. Marine Corps Forces in the Pacific (MARFORPAC). While I am not the first to observe this, I agree that the future of America and our role globally will be determined by what happens in the Indo-Pacific. We need our best there.

What We Are Doing in the Pacific

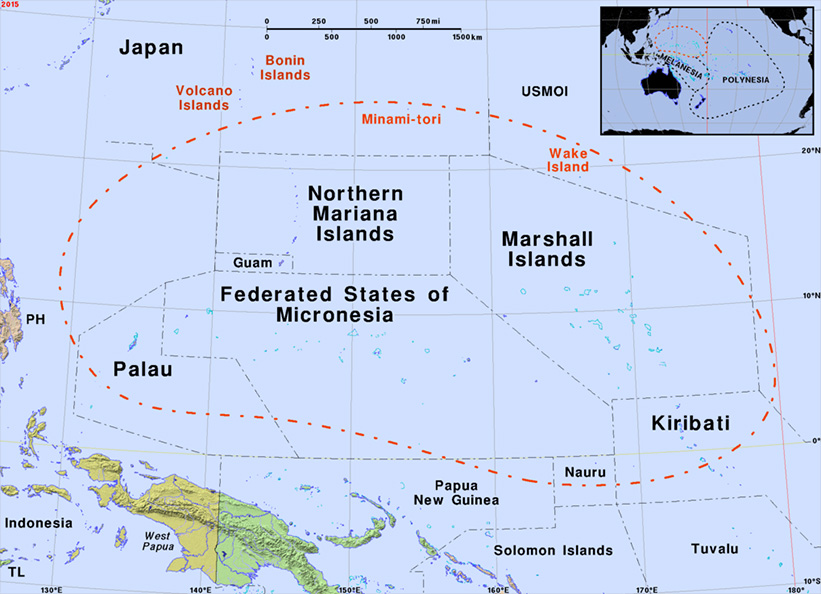

The “Freely Associated States” of Palau, Federated States of Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands—with which the U.S. recently extended a 20-year support contract, the Compacts of Free Association (COFA)—make up the bulk of one of the three major regions of Oceania, Micronesia. Together with the other two major regions, Melanesia and Polynesia (see inset), this vast area in the Pacific is known as the Blue Continent.

Ian Macky

At Embassy Koror, during my time as ambassador to the Republic of Palau, we prioritized three issues: the “3 Cs.” The first issue was the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the competition with China playing out in Palau and across the Pacific Islands. The second was climate, and how the U.S. was working with partners to help vulnerable and low-lying island nations manage this threat to their existence. The third was what we called capacity—building up human capital as well as the bricks and mortar of infrastructure projects in these remote countries to strengthen development and their connection to the global economy.

Palau is one of just 12 countries in the world that recognizes Taiwan. Although the PRC has no official relations with Palau, it is the focus of much attention from Beijing. In addition to Palau’s relationship with Taiwan, Koror’s location as the anchor of the Second Island Chain in the Pacific draws Beijing’s attention. The PRC has used coercive measures, involving criminal networks and economic pressure, to try to force Palau to switch recognition and distance itself from the U.S.

We worked hard to push back against PRC interference and to support Palau by increasing U.S. military presence and strengthening good governance. We also worked with Palau and other partners in the Pacific on issues of shared concern, such as responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, supplying U.S. vaccines to the region truly saved lives and was one of the most important accomplishments of our work in Palau.

On climate, Palau is a global leader in efforts to protect the ocean environment. While in Koror, I had the privilege to host the U.S. delegation to the 2022 Our Ocean Conference. Co-hosting with the U.S., Palau was the first island nation to welcome this major international event. The gathering brought together hundreds of representatives from government, civil society, and industry, and succeeded in raising $16.35 billion and 410 specific commitments to protect the world’s oceans.

Coming just after Palau opened its borders post-pandemic, it was a huge accomplishment for this small post. We were honored to have Special Presidential Envoy for Climate and former Secretary of State John Kerry lead the U.S. delegation. Embassy Koror contributed in its own unique way: Working closely with the Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations and in cooperation with State’s Greening Diplomacy Initiative, Embassy Koror has the distinction of being the first net-zero U.S. diplomatic facility in the world. Small posts can achieve great things.

A Call to Serve

Palau is a global leader in efforts to protect the ocean environment. Co-hosting with the U.S., Palau welcomed the annual Our Ocean Conference in April 2022. It was the first time an island nation had hosted this major international event launched by the State Department in 2014.

U.S. Department of State

In Palau, the U.S. embassy is fortunate to have a resident U.S. Civic Action Team (CAT), the only one remaining in the world. A tri-service (Navy, Army, Air Force) rotational deployment, CAT has been present in Palau for more than 50 years, well before the opening of our small diplomatic post.

The CAT team has completed millions of hours of service and support, assisting with small construction projects, providing free medical care, maintaining historic monuments and battle sites, and assisting with so many other community-focused projects and events. In terms of winning hearts and minds, these military diplomats are such an important part of our country team and whole-of-government effort to ensure we have the strongest possible relationship with Palau.

Embassy Koror continues to partner with Palau on issues of real substance and strategic consequence for both of our nations, for the region, and globally. So, for anyone in the Foreign Service who has a spirit of adventure and wants to be at the top of the wave in navigating these challenging dynamics, bid on a job in the Pacific Islands. While the embassies may be small, and service in the Pacific can be difficult, this is a unique experience with the opportunity to have an impact on issues that matter.

One of my favorite island sayings is the following: “There is an island of opportunity in the middle of every difficulty.” If you want to be on the front lines of expeditionary diplomacy, working on some of the world’s most complex and consequential challenges, consider serving in one of America’s small island posts in the Pacific.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “The Pacific Microstates and U.S. Security” by Kevin D. Stringer, The Foreign Service Journal, November 2006

- “US-Taiwan Partnership with the Pacific Islands” by John Hennessey-Niland, Global Taiwan Institute, March 2023

- “The Opening of U.S. Embassy Nuku`alofa” by Tom Armbruster, The Foreign Service Journal, January-February 2024