Through His Lens: The Legacy of Pioneering U.S. Foreign Service Officer Griff Davis

Senior USAID FSO Griff Davis was an inspiring pathbreaker who brought photojournalism and diplomacy together to chart changing times.

BY DOROTHY M. DAVIS

Griff Davis stood at the vortex of history and the future as a Buffalo Soldier in Italy during World War II, the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S., and the Independence Movement in Africa. … Through his camera, writing, and diplomatic skills, he fought for freedom and independence by documenting changing times and being on the cutting edge of changing those times by shaping image, narrative and policies. … He was both an observer and interpreter of the times.

—Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr., director, Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Harvard University

Griff Davis leaves behind a rich legacy: internationally recognized pioneer photographer, journalist, and U.S. Senior Foreign Service officer. Since September 2023 alone, six exhibitions of his photography in four countries on three continents have honored this man and his work. These include permanent installations of his photographs at the Museum of Broadway in Times Square, at U.S. Embassy Liberia, at Jazz Magazine in Paris, and in the U.S. Supreme Court Archives. Filmmaker Spike Lee even has his own personal collection.

Held at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, New York City, the exhibition, “The Ways of Langston Hughes: Griff Davis and Black Artists in the Making,” provides insight into how Davis started his unusual career path to the U.S. Foreign Service. It all began with Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes.

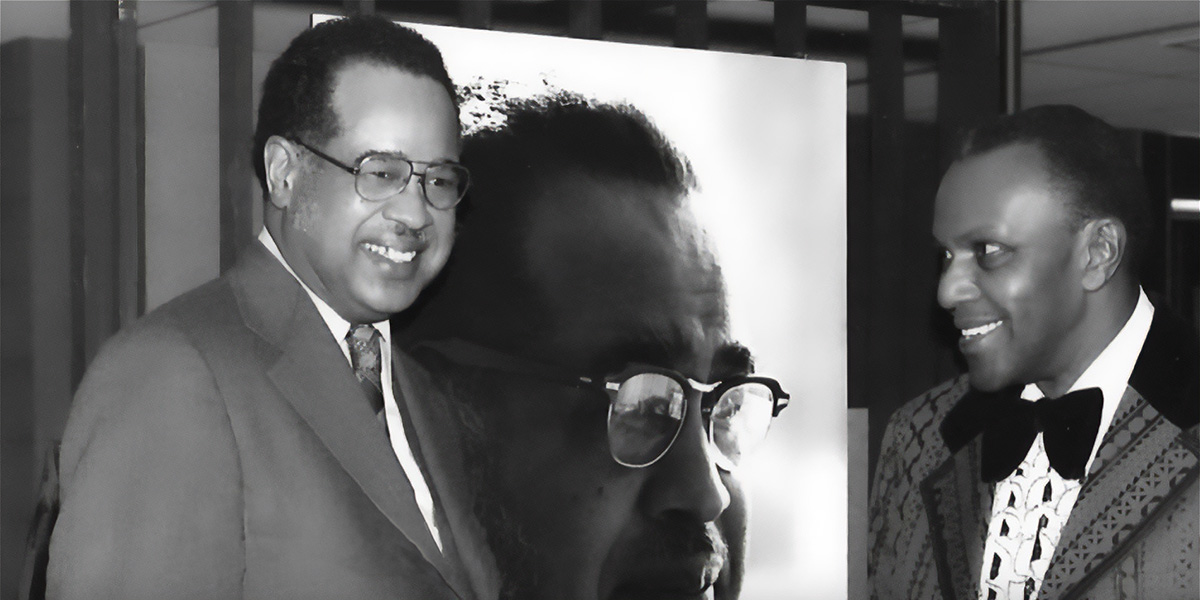

Griff Davis standing in front of a portrait of himself taken by J. Edward Bailey III (at right) as part of the “Living Legends in Black” exhibition at the Detroit Historical Museum in Detroit, Michigan, in March 1976.

© Griff Davis / Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archives

The First Steps Down an Unusual Path

In the spring of 1947, during his last semester at Morehouse College, Davis met Atlanta University Visiting Professor Hughes as a student in his creative writing class. On realizing Davis was the campus photographer for various Atlanta University campuses, Hughes enlisted him as his photographer until the end of his tenure.

Their 20-year friendship continued through Davis’ graduation from Morehouse and landing his first job, as the first roving editor of Ebony magazine. Hughes had recommended Davis to John H. Johnson, founder and publisher of Ebony. After 18 months at the magazine, Davis went to Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, again at the recommendation of Hughes. He was the only Black American student in the class of 1949.

While attending Columbia, Davis rented a room in Hughes’ Harlem home and sometimes accompanied Hughes on assignment as his photographer. Shot during one of these assignments, Davis’ photograph of legendary actor Canada Lee is now permanently installed in the Museum of Broadway in Times Square.

Davis simultaneously took a photojournalism course taught by Kurt Safranski at the New School. Safranski was one of three Jewish émigrés who escaped Germany during World War II and brought the photojournalism industry to the United States through their creation of Black Star Publishing Company, the first privately owned picture agency in the U.S. Most famously, Safranski was responsible for helping Henry Luce create Life magazine.

After graduation, Davis was hired as the first and only Black American international freelance photojournalist at Safranski’s company. Said the late Benjamin J. Chapnick, onetime president of Black Star, the co-founders “considered [Davis] one of the best photojournalists of his generation.”

Cutting His Teeth Abroad

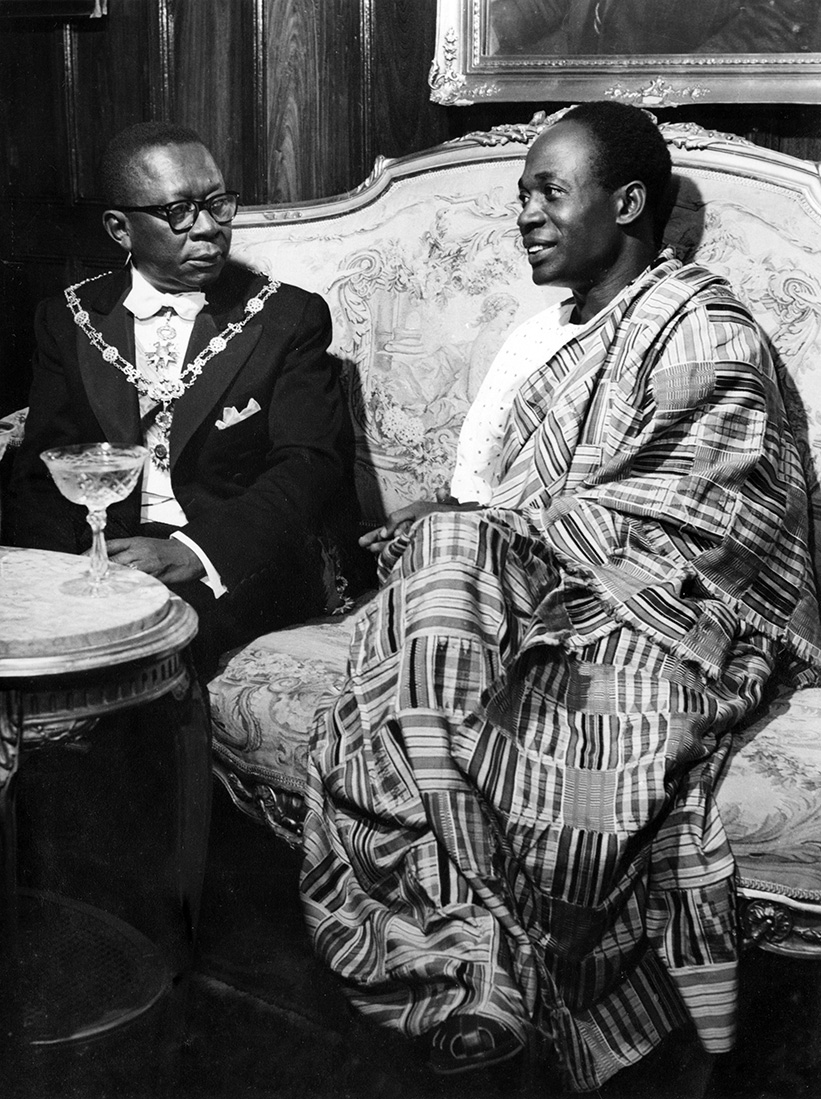

Official commissioned photograph of President William V.S. Tubman (at left) and Prime Minister of Gold Coast (Ghana) Kwame Nkrumah in Monrovia, Liberia, in January 1953.

© Griff Davis / Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archives

Davis’ first trip overseas was to Liberia, where he covered the missionary movement and iron ore industry in 1949. He wrote: “Africans across the continent had begun to scream for their independence. The spirit of the African people and their strong desire for freedom captured my photo-journalistic instincts to witness the rebirth of a continent and the birth of new African nations.”

Working for Black Star from 1949 to 1952, Davis made three separate trips to Liberia and other parts of Africa and Europe. In addition to being a stringer correspondent for The New York Times, he had stories and photographs appear in a host of publications in the U.S. and Europe, including the Saturday Evening Post, Time magazine, Fortune, Life magazine, Ebony, and Der Spiegel. While in Liberia, he was even asked by Ebony to interview Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia for the cover story, “The Private Life of Emperor Selassie,” in its November 1950 fifth-anniversary issue.

Of the 521 photographs Davis took for Black Star, eight of Liberia were featured in the recent exhibition, “Stories from the Picture Press: Black Star Publishing Company and the Canadian Press,” at the Image Centre at Toronto Metropolitan University. As an offshoot of the exhibition, the Image Center’s book, Facing Black Star, includes a full chapter, titled “Telling on Archival Erasure: The Stories Behind Griffith Davis’ Liberia Photographs.”

At the time Davis started to freelance for Black Star, President Harry S. Truman outlined the Point Four program in his 1949 inaugural speech. It was the fourth point that established the U.S. policy of technical assistance and economic aid to underdeveloped (now referred to as “developing”) countries, the forerunner of the present-day U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The first appropriations under this program were made to Liberia in 1950, laying the groundwork for Davis’ Foreign Service career.

Joining the Foreign Service

During his time with Black Star, Davis developed the trust and a professional friendship with President of Liberia William V.S. Tubman. As he finished editing Liberia’s first promotional film, Pepperbird Land (1952), John W. Davis (not related), first director of the Point Four program of the U.S. diplomatic mission there, encouraged Davis to apply for employment with the U.S. government and do “picture stories.”

After passing the Foreign Service exam in the summer of 1952, Davis and his newlywed wife, Muriel Corrin Davis, returned to Liberia that November. As the first information officer and audio/visual adviser of the U.S. embassy in Monrovia, he became one of the pioneers of President Truman’s program for foreign aid.

Under the initial leadership of the first African American ambassador, Edward R. Dudley, the program was established worldwide during the Jim Crow era, in part due to their efforts. In this capacity, Davis ultimately became a trailblazer for Black Americans in the U.S. Foreign Service. (Forty-two of Davis’ photographs of U.S. Embassy Monrovia under the leadership of Ambassador Dudley are included in the PBS American Experience/Flowstate Films documentary “The American Diplomat” that aired in February 2022.)

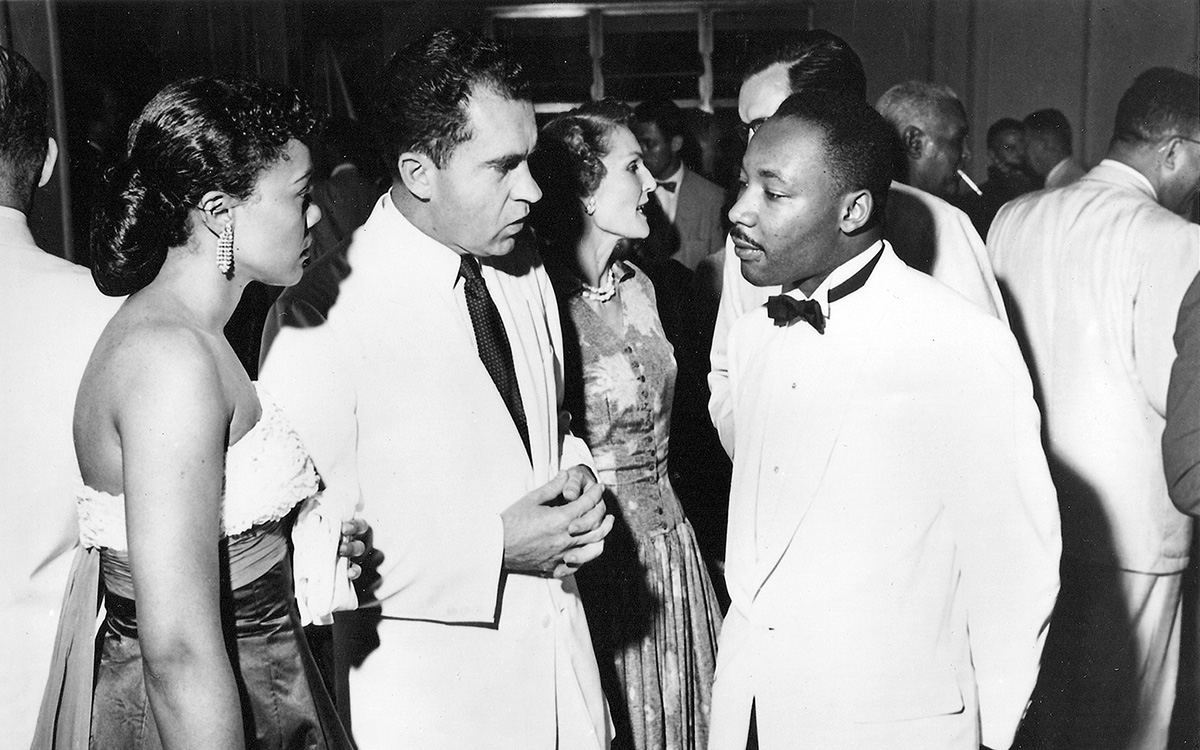

Vice President Richard Nixon and Second Lady Patricia Nixon unexpectedly meet Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta Scott King, for the first time during independence ceremonies in Accra, Ghana, on March 6, 1957. Griff Davis took this famous shot. The photo is included in the newly released 2024 official biography, The Mysterious Mrs. Nixon: The Life and Times of Washington’s Most Private First Lady, by Heath Hardage Lee and remains in the archives of the King Center in Atlanta, Georgia.

© Griff Davis / Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archives

Davis' Influence Through Images

In Liberia (1952-1957) and the newly independent Tunisia (1957-1962), Davis assisted the governments in establishing their respective ministries of information and broadcasting. During Davis’ years in Liberia, President Tubman commissioned him to do a one-man exhibition of 100 images about Liberia, titled Liberia 1952, at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. This was at a time when African Americans were not allowed to show in that museum.

He also commissioned Davis to do a two-page picture story on Gold Coast (Ghana) Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah’s visit to Liberia for Time magazine’s Feb. 9, 1953, edition and four documentary films: the official inauguration films of 1952 and 1956 of President Tubman for the government of Liberia; Progress Through Cooperation, on Liberia’s agricultural development program in 1957; and the aforementioned Pepperbird Land, the first promotional film of Liberia (and possibly any noncolonized African country at the time).

During this period of President Tubman’s presidency, Davis took a total of 7,000 images of Liberia. From 2009 to 2011, U.S. Ambassador to Liberia Linda Thomas-Greenfield displayed four of those photographs in her residence through the Art in Embassies program. In 2012, Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield permanently installed them in the new U.S. embassy she christened that year. In attendance, Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf reflected: “Most Liberians have fond memories of Muriel and Griffith, who did so much to promote the historical memories of Africa’s first independent nation through Griffith’s remarkable photography.”

Before ending his tour of duty as a Foreign Service officer in Liberia, Davis was assigned by U.S. Information Service headquarters in Washington, D.C., to be the official photographer for the U.S. delegation led by Vice President Richard Nixon to Ghana’s Independence Day celebrations on March 6, 1957. He was one of only 20 photographers in the world granted official credentials to cover this historic event.

Arguably, his most famous photograph was of the unexpected first meeting of Richard Nixon and Second Lady Patricia Nixon with Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King at one of the Independence Day receptions. (Davis and King had grown up together in Atlanta.) Having ended the Montgomery Bus Boycott only a few months before, the Kings were invited to the Independence Day celebrations by Prime Minister Nkrumah. It was the first trip to Africa for both couples. The U.S. government banned the photograph from being publicly published due to the volatile nature of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement at the time.

Work in Education

“Liberian Woman Walks Alongside Iron Ore Train,” 1952, by Griffith Davis. It was the second place winner of USAID/ FrontLines 50th Anniversary People’s Choice Global Photo Contest in 2011.

© Griff Davis / Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archives

During the Biafran War in Nigeria (1967-1970), Davis assisted the federal and regional ministries of education in utilizing radio and television for educational purposes. He served as the deputy chief education officer of USAID/Lagos, which coordinated U.S. technical assistance to joint U.S.-Nigeria education projects and the restoration of the eastern region education facilities destroyed by the war.

Between 1973 and 1983, Davis was assigned to USAID’s Washington headquarters, where he directed the Information, Education, and Communication Branch of the Office of Population, which backstopped family planning programs worldwide. This assignment expanded his impact beyond Africa. Approximately 1,500 foreign nationals from 102 countries were trained in U.S.-based summer workshops and MA and PhD degree programs, principally held at the University of Chicago under the direction of Donald Bogue. Davis managed all of these workshops and programs for USAID.

He was nominated by President Ronald Reagan to the U.S. Foreign Service rank of Counselor, which was ratified by the Senate in the congressional record of Sept. 26, 1981. He retired from the Foreign Service in 1985.

A Prolific Life and Body of Work

From 1952 to 1985, Griff Davis worked in many capacities for USAID. As an adviser to African governments such as Liberia, Tunisia, and Nigeria, and to the Bureaus for Africa and Population and Humanitarian Assistance, he had the fortuitous opportunity to document in rare still photographs and motion pictures historic moments in the developmental evolution and activities of the first years of independence of many African countries and African leaders. He also repeatedly traveled to more than 25 of Africa’s then 51 countries, and to several European countries, during his career.

After retiring to his hometown of Atlanta in 1985, Davis periodically served as an official escort for more than 50 international visitors brought to the United States by the U.S. Information Agency. He tried to initiate the concept of having escorts like himself document the visits through photographs as well as written reports, so that these visitors could have a lasting visual memory of their experiences in the United States.

Before he died, in July 1993, Davis’ friends from Atlanta curated his final exhibition, “An Exhibition Honoring the Career of Griffith Jerome Davis, Photographer, Journalist, Diplomat and Native Atlantan,” at the Atrium on Sweet Auburn in Georgia.

My father received multiple awards for his work during his lifetime and posthumously, and I dedicate the Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archives to excavating, highlighting, and sharing his images and stories. May he serve as an inspiration to others to take the road less traveled.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Photos by 19th Century Photographer Griffith J. Davis are Again in the Spotlight” by Sandra Dawson Long Weaver, Morgan State Global Journalism Review, February 2020

- “Kennedy, Nixon and the Competition for Mr. Africa, 1952-1960” by Gregory L. Garland, The Foreign Service Journal, September 2022

- “Griffith Davis,” WEDU-PBS Arts Plus, August 2023