Beijing Beginnings

Reflections

BY BEATRICE CAMP

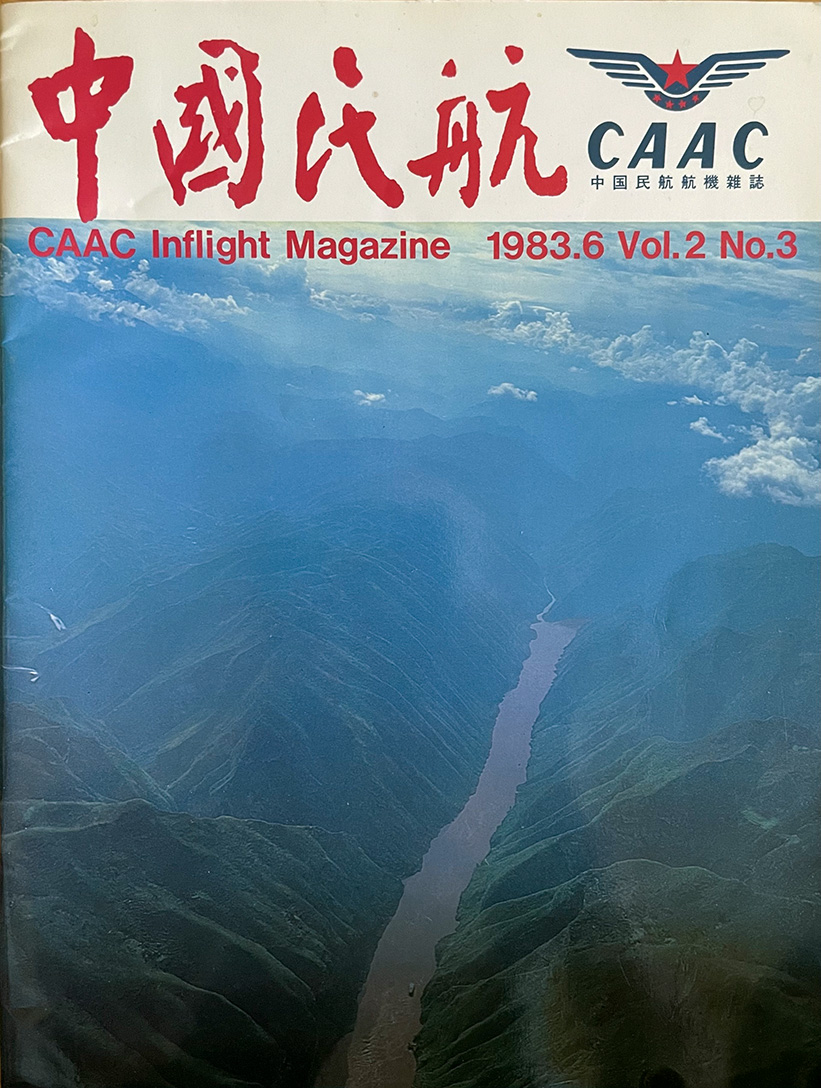

The front cover of the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) in-flight magazine, 1983.

Courtesy of Bea Camp

Flying into Beijing in 1983 after a year at the Foreign Service language school in Taipei required a transit in Hong Kong. It also meant resuming use of the diplomatic passports that were kept out of sight in Taiwan, in recognition of our nondiplomatic relationship there.

We still have a copy of the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) in-flight magazine from that journey. After a year in Taiwan—surrounded by slogans about retaking the mainland and exhibits demonstrating poor living conditions there—we anxiously read the magazine for clues to what awaited us in the coming two years at Embassy Beijing.

An article, “A Paean in the Blue Sky,” praising the passenger service explained that the stewardesses received hundreds of commendation letters about their “quality service” from passengers: “In a collective full of vigor … they worked tirelessly for the happiness, comfort, and safety of hundreds and thousands of passengers.” This even included holding a barf bag for a passenger. Somehow the article didn’t match our experience.

This alien-to-us world continued to reveal itself, starting with the dark road into town. The PRC had a law against using headlights at night so as not to blind oncoming bicyclers. Traffic on the two-lane road from Capitol Airport that hot August night was impeded by elderly men crouched on the street playing cards under the weak streetlights. The men moved for our car to pass, then returned to their spot.

Bicycles were still the main mode of transportation in Beijing. My husband and I brought from Taipei two powder-puff-blue 10-speeds made by a new Taiwan company called Giant. Our choice was fortunate in many ways: At that time, purchasing a bike in the PRC required a letter of authorization from the buyer’s work unit, in our case an official document from the U.S. embassy.

As we commuted to the embassy from our temporary quarters in the Huadu Hotel, curious Beijingers gawked at our glamorous, super-modern rides. (In Beijing, all bicycles were black, one-speed, and heavy.) Although we were initially reluctant to reveal our bikes were from Taiwan, questioners were thrilled they were made in China.

In contrast to our well-heated embassy, Chinese offices were near freezing in the winter, so we learned to dress warmly on official visits. Escorted to a meeting room and served copious tea, we would drink to keep warm. Once bladders reached capacity, it was time to leave. The officials coped by wearing pink silk long underwear, which peeked out colorfully below the cuffs of their blue Mao suits. Soon we all bought such underwear.

This alien-to-us world continued to reveal itself, starting with the dark road into town.

But changes were afoot. During President Ronald Reagan’s 1984 visit, the White House decision to serve Western food at a banquet dinner flummoxed the Chinese guests, who found plated food confusing and unsatisfying. Plus, as one told me, when you eat it, “an hour later you are hungry again.”

The restriction on diplomats driving more than 25 kilometers from the city center was loosened slightly to allow road trips to Tianjin, the closest major city about 130 kilometers away. Itching to hit the open road, we jumped in our car for steamed buns at an innovative restaurant there, which served food straight through from lunch to dinner—an unusual move.

On the way we bought a traditional merchant bed that an eager seller had positioned along a narrow lane. As we later learned, “Tianjin people can sell anything to anyone.” The once-denounced entrepreneurial spirit was back in force.

Gradually we witnessed more societal shifts, often just in small ways, as the PRC embarked on “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” When bananas appeared for the first time, word spread like wildfire, and the diplomatic community all rushed to buy this previously unseen commodity. Three months later, another banana boat arrived from Central America, sparking the same rush.

By the time we left Beijing, bananas were regularly available and headlights had gone from forbidden to required. What did not change, however, was the quirky and unpredictable CAAC service—despite many adventures with the official airline, we were never tempted to send a letter of commendation.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.