Pioneer, Bridge Builder and Statesman—A Conversation with Ambassador Edward J. Perkins

Ambassador Edward J. Perkins is the 2020 Recipient of the Award for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy.

NOTE: Ambassador Edward J. Perkins died on Nov. 7, days before this interview about his life and work went to press. He was 92. We extend our condolences to the family and are particularly grateful to his daughters, Katherine and Sarah, for helping to make this well-deserved tribute possible.

President Ronald Reagan talks with Ambassador to South Africa Edward J. Perkins at the White House in May 1987. Seated at right are Secretary of State George Shultz, U.S. National Security Adviser Frank Carlucci and, at far right, National Security Council Senior Director for Africa Hank Cohen.

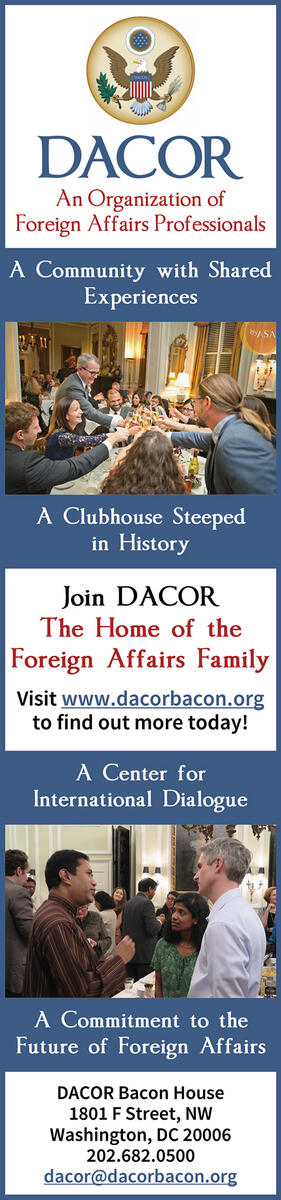

Edward J. Perkins on patrol in Korea, 1947

Career Minister Edward J. Perkins, a four-time ambassador, is this year’s recipient of the American Foreign Service Association’s Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award.

Ambassador Perkins is the 26th recipient of this prestigious award, given annually in recognition of a distinguished practitioner’s career and enduring devotion to diplomacy. Past honorees include George H.W. Bush, Thomas Pickering, Ruth A. Davis, George Shultz, Richard Lugar, Joan Clark, Ronald Neumann, Sam Nunn, Rozanne Ridgway, Nancy Powell, William Harrop and Hank Cohen. The AFSA Awards Ceremony, originally scheduled for Oct. 18 at the State Department, has been delayed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Edward J. Perkins was born in Sterlington, Louisiana, on June 8, 1928, and grew up in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and Portland, Oregon. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Maryland and master’s and Doctor of Public Administration degrees from the University of Southern California.

He served in the U.S. Army for three years and later spent four years in the U.S. Marine Corps. He worked for the State Department after the Marine Corps and joined the U.S. Foreign Service in 1972.

In 1978, Mr. Perkins was assigned to Accra, Ghana, as counselor for political affairs, serving there for three years. From 1981 to 1983, he was deputy chief of mission in Monrovia, Liberia. Returning to Washington, he directed State’s Office of West African Affairs until 1985, when he was appointed ambassador to Liberia.

The following year, he was confirmed as ambassador to the Republic of South Africa, where he served until 1989. He was the first Black U.S. ambassador to serve in that country. Ambassador Perkins was then appointed as Director General of the Foreign Service and Director of Personnel in the Department of State, serving in that position for three years. In 1992, he became U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, and U.S. representative on the U.N. Security Council, serving in that capacity until 1993, when he was named U.S. ambassador to Australia, his final Foreign Service posting. On Aug. 31, 1996, Ambassador Perkins retired from the Foreign Service with the rank of Career Minister.

Perkins and his wife-to-be, Lucy Ching-mei Liu, shortly after they met in Taipei in 1958.

During his 24-year diplomatic career and in “retirement,” Ambassador Perkins received numerous awards, including the Presidential Distinguished and Meritorious Service Awards and the Department of State’s Distinguished Honor and Superior Honor Awards; and in 2001, the State Department presented him with the Director General’s Cup. In 1992 George Washington University named him Statesman of the Year. He is an active member of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity and, in 1993, received their highest honor, the Laurel Wreath Award for Achievement and Diplomatic Service.

Following his retirement from the Foreign Service in 1996, he was appointed as the William J. Crowe Chair and as executive director of the International Programs Center for the University of Oklahoma, serving from August 1996 until December 2010. He also served as a senior adviser at The Stevenson Group, a Washington, D.C.–based consulting firm.

Ambassador Perkins has served as the Distinguished Jerry Collins Lecturer in Public Administration at Florida State University; as a member of the Presidential/Congressional Commission on the Public Service; and as a member of the White House Advisory Committee on Trade Policy and Negotiation. He is a member of and has served on the boards of numerous professional associations in the areas of defense and international affairs.

In 2006 the University of Oklahoma Press published Ambassador Perkins’ memoir (written with Connie Cronley), Mr. Ambassador: Warrior for Peace. He has also co-edited several books, all published by the University of Oklahoma Press: The Middle East Peace Process: Vision versus Reality, with Joseph Ginat and Edwin G. Corr (2002); Democracy, Morality and the Search for Peace in America’s Foreign Policy, with David L. Boren (2002); Palestinian Refugees: Traditional Positions and New Solutions, with Joseph Ginat (2001); and Preparing America’s Foreign Policy for the 21st Century, with David L. Boren (1999).

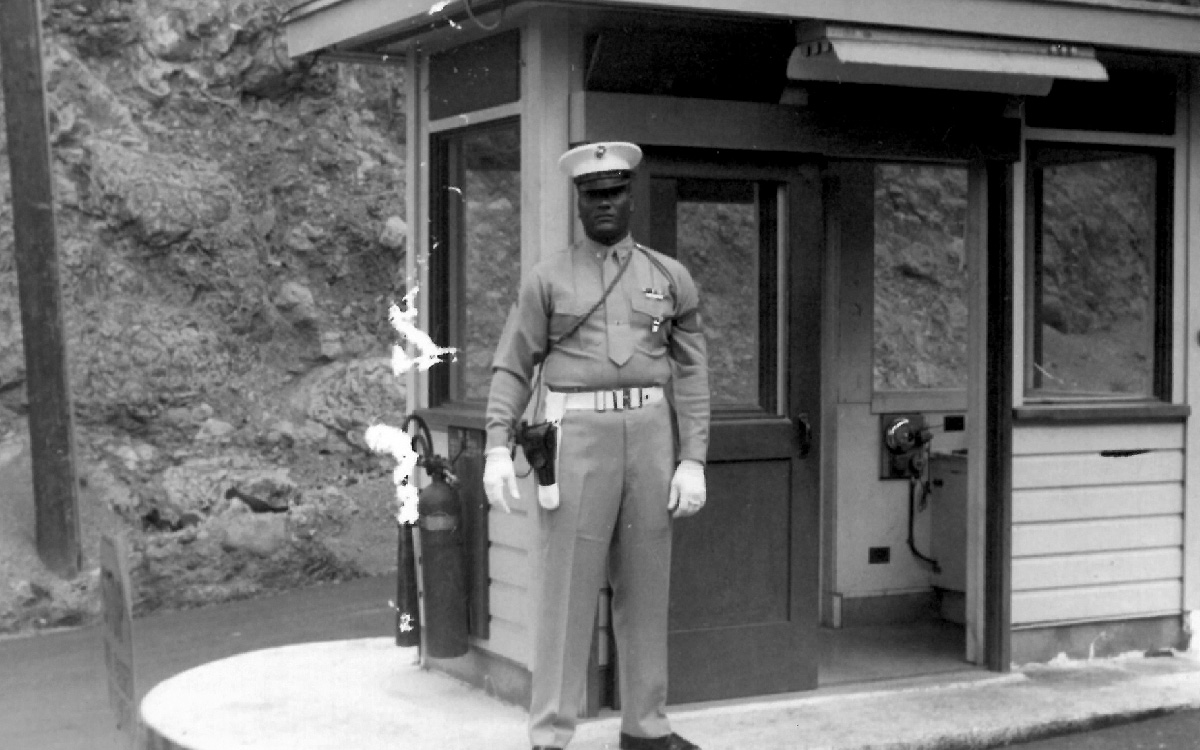

Ambassador Perkins’ beloved wife, the former Lucy Ching-mei Liu, passed away in 2009. They have two daughters, Katherine and Sarah, and four grandchildren.

FSJ Editor-in-Chief Shawn Dorman worked with Katherine and Sarah to conduct the following interview with Ambassador Perkins in September. All photographs are courtesy of the Perkins family.

Early Days and Joining the Foreign Service

FSJ: Tell us a little bit about your childhood. Where did you grow up?

EJP: I was born in 1928 in Sterlington, Louisiana. My mother attended a college where she met my father, who was studying to become a minister. They got married without the consent of my grandparents; shortly thereafter, I was born. They divorced, and my mother took me back to her parents’ 360-acre farm in a town called Haynesville, in northern Louisiana, where she had grown up with nine siblings. All the siblings would eventually leave the farm except for my Aunt Savannah, who helped raise me.

When my mother and I lived on the farm, she met her second husband, Mr. Grant, at Pleasant Grove Church where he was leading a church group (he was a traveling minister). My mother began to see him against the advice of my grandparents, who didn’t trust traveling ministers. During one of his visits to the farm, he asked my mother to marry him, and when they left for Pine Bluff, Arkansas, she told my grandmother that she would eventually send for me.

I continued to live with my grandparents and my Aunt Savannah; this arrangement seemed the most natural thing in the world. I called my grandmother Mama—she brought me up with love and strict discipline. I moved to Pine Bluff when I was 14 to live with my mother and Mr. Grant; and we later moved to Portland, Oregon, where I graduated from Jefferson High School in 1947. I was accepted to go to Lewis and Clark College, but at the last minute, without telling my mother, I decided to enlist in the Army.

FSJ: When and how did you decide you wanted to be a diplomat?

EJP: When I left the Army in 1950 and became a civilian working for the military, I met American diplomats whose work intrigued me, and decided that I wanted to do the same thing. I realized that I had to get a college degree, and with the guidance and gentle push from a mentor, I moved back to the United States in 1953 and enrolled at Lewis and Clark College; as it was, the pull of overseas living overcame my desire to get a degree at that time. One of my classmates who had just delisted from the Marine Corps told me that his experience had made him a better person. I decided that the Marines was going to be my next adventure; it was one of the best decisions I made.

FSJ: You served in both the Army and the Marine Corps overseas. How did military service help prepare you for the Foreign Service?

EJP: When I joined the Army, I trained in Fort Knox, Kentucky, for 10 weeks before being sent overseas to Korea and then Japan. In Japan, I was assigned to the Army’s central personnel department in the 212th Military Police Company, where I learned about administration and the concept of personnel management. Later, the Marine Corps helped me learn self-discipline and focused my attention on the things that one needed to succeed. I enrolled in a self-study correspondence program at the University of Maryland to get a university degree. My military experience also exposed me to other countries and cultures, an opportunity I would not have had if I stayed in Oregon.

The Perkins family in 1983 at Katherine’s graduation from the Emma Willard School in Troy, New York. From left: Perkins, Sarah, Katherine and Mrs. Perkins.

FSJ: Is it correct that you met your late wife, Lucy Ching-mei Liu, in Taiwan, and that both your daughters were born while you were serving in Asia with the U.S. military?

EJP: Yes, I met my wife, Lucy, in Taiwan. She was from a beautiful city called Miaoli. I was working as a personnel officer for the military exchange service in Taipei and she was one of the clerks in the same office. It took me a year to gain enough courage to ask her out for dinner. I took her to the Grand Hotel, owned by Madam Chiang Kai-shek, for our first date. When I first asked Lucy to marry me, she said no because her father would never agree.

When I asked again sometime later, she suggested that we elope and then tell her parents that we were married. I didn’t think it was a good idea; but after her parents declined my proposal and locked her in her room in the house where she grew up, we ended up eloping after Lucy’s dramatic escape. Her parents finally came around after meeting our children when they visited Thailand. They came and stayed with us in Bangkok and presented me with a gift of two scrolls as a symbol of peace and reconciliation. My daughters were born overseas: Katherine in Japan, when I was working for the U.S. military, and Sarah in Thailand, when I was working with USAID.

FSJ: When did you join the Foreign Service? What was the application process like?

EJP: I joined in 1972. When I was working for USAID in Bangkok, I decided to take the Foreign Service examination. Nicholas Thorne, who was the administrative coordinator for Southeast Asia at U.S. Embassy Bangkok and a former Marine, was key to my success. He was able to arrange for me to take the written exam in Thailand. After I passed, I had to travel to Washington, D.C., to take the oral exam. Thorne assisted in arranging my travel by military air. He gave me advice on how to prepare and told me to read the back issues of Newsweek and newspapers, particularly the international sections. I had five days to further prepare after I arrived in D.C., and a friend pressed me on everything from art to quantitative analysis and world politics. I went to the bookstore and picked up a book about French artists that included Pablo Picasso. One of the photos was of a sculpture by Picasso, which I had previously seen during a visit to Paris. During the oral exam, I was asked whether I liked art; I told them about my love of Picasso and that particular sculpture. They questioned me about this sculpture, appearing doubtful of my knowledge, and were shocked when I was able to tell them more than they had expected.

Some 10 years later I was about to embark on an ambassadorial assignment to Liberia and met one of the examiners, who told me they had asked random questions during my oral exam because they didn’t believe I knew anything about the world. While I had surprised him 10 years earlier, he was even more shocked to hear that I was going to Liberia as ambassador. But my desire and dream to be a Foreign Service officer and my life experiences had prepared me. I am grateful that the few people who believed in my dream were there to provide the support and guidance I needed to make it a reality, and one of them was Nicholas Thorne.

FSJ: You joined the Foreign Service not long after the civil rights movement gathered momentum. Did you find the State Department to be welcoming?

EJP: There were no other Black diplomats in my orientation class. There were only 20 or so around the world, and most of them were posted to Africa. The department was not welcoming at the time, and Blacks in the Foreign Service faced prejudice.

When I was looking for an assignment in one of the geographic bureaus, none of the bureaus wanted me. There were no “vacancies,” even with the support of then Executive Secretary (and later Secretary of State) Larry Eagleburger. I was selected to be deputy chief of mission in Mozambique, but the ambassador there opposed me, saying he needed someone who had experience as a reporting officer, which I did not have at the time. So I was sent to Accra as political officer.

U.S. Ambassador to Liberia Edward J. Perkins presents his credentials to Liberian Head of State Samuel K. Doe on Aug. 28, 1985.

U.S. Embassy Accra Political Counselor Edward Perkins, second from right, engages with a tribal chief in Ghana in 1978.

Overseas Assignments

FSJ: What was that first overseas posting like?

EJP: When I arrived in Accra in 1978, I was the only one in the political section except for a few CIA operatives. However, I did not let that stop me from striving to be the best political officer the post had ever seen. As a result of my efforts, I received the annual global reporting award.

Despite my family and I living through a bloody coup, I enjoyed my time in Ghana. It was a beautiful country, rich in culture and scenery, and I could not have asked for a better first assignment. The Ghanaians are an interesting, open and welcoming people. I developed networks in all areas of Ghanaian society. Pretty soon, it seemed that everywhere I went in Ghana, I was known. I took the job as a political reporting officer seriously, following the advice Mao Tse-tung gave to his army: “Be a fish in the sea. Swim among the people. Get to know them.” That was also the great Sun Tzu’s philosophy.

One of the highlights of my time in Ghana was when another Black FSO, James Washington, and I found the grave of W.E.B. DuBois, the father of the civil rights movement in America. DuBois was also the first Black man to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard and was one of the founders of the NAACP. He had left the United States at the age of 92 and moved to Ghana, where he died. Nobody remembered where he was buried. We found the plaque that marked his grave, cleared the overgrown site and sent a photograph to the NAACP publication where it was featured in the issue commemorating the magazine’s 100th anniversary.

FSJ: What was it like serving as deputy chief of mission and later ambassador to Liberia?

EJP: After my tour in Ghana, I was assigned as the deputy chief of mission in Liberia for Ambassador Bill Swing. He was still awaiting confirmation, so I went directly from Ghana to Liberia, had some overlap with the outgoing DCM and served as chargé until Ambassador Swing’s arrival. Monrovia was a post where there were many administrative issues, given the large number of U.S. government agencies represented. USAID had a big program, as well as the Voice of America, which had the largest station in Africa there. This new reality required me to make a big switch in my approach. There were also many political concerns.

The country had undergone a coup prior to my arrival in 1981, and some of the previous leaders who were descendants of former American slaves (called Americo-Liberians) had been executed. The current leader, Samuel K. Doe, was a former Army sergeant with little education. There were tensions between the Americo-Liberians and African Liberians, and it was my job to try to work with these two groups. The Americo-Liberians expected the United States to support them and help overthrow the president and return things to where they had been in the past, while the African Liberians wanted justice and compensation for the way they had been historically treated like slaves. I told both groups that it was the U.S. position to support Liberia as a country and as a people, not just one particular group.

FSJ: President Ronald Reagan tapped you as the first Black U.S. ambassador to apartheid South Africa in 1986. What was your mission there, and how did you manage it?

EJP: When President Reagan interviewed me for the job, he asked me what I would want to accomplish in South Africa, and I told him that I would try to change the system using the power of his office. He asked me how I would do it. I told him that I would get to know the Black South Africans, as well as other South Africans. I told him that we didn’t know Black South Africans well, that they were suspicious of the United States, and we needed to gain their trust. I added that we needed to work toward a peaceful transition in South Africa, and we needed to convince the Afrikaner government that their time was up. Finally, I told him that I would expect to speak on his authority, and that everything I would say would be on his behalf.

It was difficult and challenging because the Afrikaners were a small group of people who had come from Flanders to South Africa to start a new life; they felt people were trying to take away the lives they had built over hundreds of years. I told President Reagan that the denial of rights to the other racial groups in South Africa was untenable and could not continue, but that it would be my job to understand all the actors in the country, by meeting them.

Edward Perkins greets Nelson Mandela and his wife, Winnie, at the Jefferson Room in the Department of State during Mandela’s first visit to the United States, June 1990.

FSJ: I read that when you found a totally segregated society in South Africa, you said: “Our embassy must be a giant change agent.” Can you tell us about the significance of attending the Delmas Treason Trial and about your attempts to visit Nelson Mandela in jail?

EJP: The Delmas Treason Trial was the trial of 22 anti-apartheid activists, including three senior United Democratic Front leaders: Moses Chikane, Mosiuoa Lekota and Popo Molefe. The men used peaceful protest to let the country know that apartheid was wrong; the Afrikaner government accused them of terrorism and wanted to use their trial and resulting sentences as a lesson to others. The trial took place in the small village of Delmas, in northwest South Africa. I decided to attend but did not make my decision public.

At the last minute, the political officer and I got in the car and told the driver to take us to Delmas. The driver, who we knew was a government operative, tried to stall by telling me that he needed to change the oil. I told him to stay in the car, that he would not get the opportunity to tell the government of our movements. He was frightened but drove us to Delmas. When I walked into the courtroom, everyone went silent; by the time the court recessed, the three senior UDF members had made the decision to meet with me and had already outlined their requests related to their prison conditions on paper. For example, they wanted all of the Time magazines going back six months plus issues of The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times. Delmas became well known throughout the world.

I let it be known to the government that I was trying to get inside the prison to meet Nelson Mandela. I sent letters to the Minister of Justice after attending the Delmas Treason Trial. I also called on him to ask permission to visit his most famous prisoner, and his response was always “it isn’t time.” I always replied: “Your time will never equal my time, so I will save my request till next week.” Every week I sent a letter, and he sent the same response. During my last week as ambassador, I told him to talk to his president to give the U.S. permission to visit, noting that the minister did not want to be known as the person who barred me. He never vocalized the reasons for the decision, but his expression told me that it was out of his hands.

FSJ: Do you think that U.S. embassies and diplomats can still be change agents in the world? What advice do you have for today’s FSOs?

EJP: Yes, I do believe that U.S. embassies and diplomats can still be change agents. When serving overseas, diplomats should strive to get access to all parts of host-country communities to make a difference. This means representing the United States at its best. American diplomats should also be a reflection of the various communities that we come from and make the effort to represent the best parts of our society. I would advise them to do what I did—learn to represent not just the State Department, but the heart and soul of the United States. To do this, you need to understand the Constitution and the various constituencies of our country.

FSJ: A 1987 Time magazine article, “Quiet Sting: A Diplomat Makes His Mark,” described you as “cultivating a low profile, then discarding it at strategic intervals to issue carefully chosen shots.” That sounds like an excellent strategy. Can you tell us about a time it worked well?

EJP: As part of my strategy in South Africa, I needed to get to know Afrikaners and visit the communities where they lived. I traveled to a couple of towns, but the one that affected me most was an Afrikaner village three miles from Pretoria whose population ranged from the very poor to the well off. We parked the car on the outskirts of town, and I walked up and down the streets and observed people of various ages; they also looked at me carefully, wondering what I was doing there. Finally, someone came up and asked who I was; they couldn’t believe I was the U.S. ambassador. I talked to three Afrikaner women; it was my way of letting them know that I represented the United States in South Africa, and I was not going to become a myth by keeping myself apart from the people.

FSJ: You served as ambassador to the United Nations from 1992 to 1993. What was your impression of the United Nations then? How do you think that role and standing have changed?

EJP: The role as I understood it, especially after my conversation with President George H.W. Bush, was that the United Nations existed to make a difference. With that in mind, my approach was to cultivate relationships with all members of the U.N. Security Council and as many members of the General Assembly as I could.

In my view, the U.N. still exists to make a difference, but the U.S. view of the U.N.’s role is always influenced by the view of the current U.S. president. When I was there, I had the support of President Bush, who wanted to effectively use the U.N. to make changes. He had an open line and made it possible for me to call him whenever there was a resolution that needed his guidance. I was able to work closely with the president and Secretary of State Larry Eagleburger on sensitive issues. President Bush respected the U.N. and its mandate, and understood how it could support and advance U.S. interests.

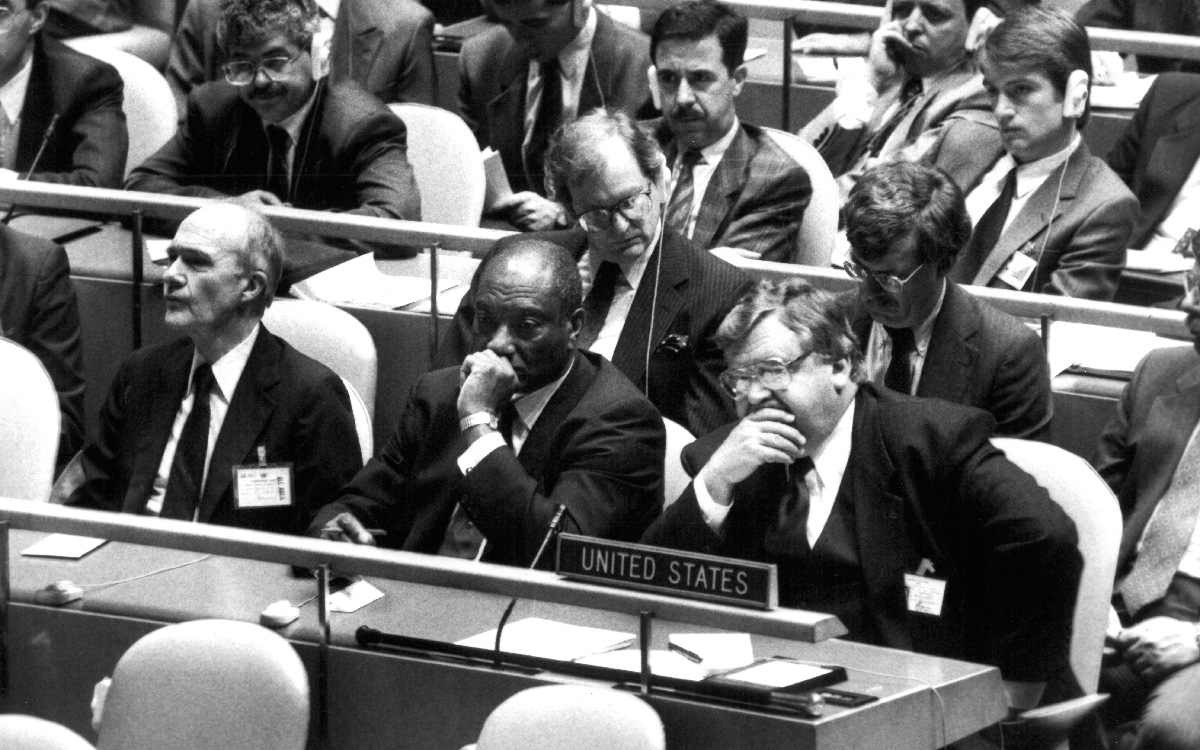

U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Edward J. Perkins and, at right, U.S. Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger at the United Nations General Assembly in 1992.

Washington Assignments

FSJ: You spent time in Washington working on personnel issues and rose to the top job of Director General in 1989. What was the priority issue for you as Director General?

EJP: The first priority issue was remaking the Foreign Service to better support U.S. economic prosperity. At the time, U.S. foreign economic policy was going through a rebirth, which meant that officers in the economic cone needed to be pushed in new directions, while all other officers in other cones had to be reminded of the importance of economic issues. We worked closely with the Department of Commerce on this initiative because they had been encouraged by Congress to play a more active role overseas supporting U.S. companies and investments.

The second priority was giving full attention to two important personnel issues: getting more minorities and more women into the Foreign Service. To do that, we had to mobilize support in the building and on Capitol Hill. Groups like the Congressional Black Caucus played a major role in helping to get authorization for these initiatives in the State Department’s budget.

Shortly after I became Director General, I recognized that the department needed to improve its outreach to communities outside Washington, D.C., such as the Appalachian region. State did not recognize the value of recruiting officers from regions such as this one. As part of the outreach strategy, I organized visits by Department of State personnel to state governors. I, myself, visited Governor Douglas Wilder of Virginia. I told him that we needed assistance from governors to recruit from their communities that may not have exposure to foreign policy or international issues.

FSJ: Can you tell us about the Thursday Luncheon Group?

EJP: Several of us founded the Thursday Luncheon Group with only a few members, including officers from what was then the U.S. Information Agency. I realized the value of having a support and advocacy group for Black officers and actively recruited more African Americans at State to join. I also recognized the need for advocacy work and organized members to visit the Congressional Black Caucus to discuss ideas for a recruitment program targeted toward minorities. This resulted in a law that required the State Department to create what became the Pickering Program. The Thursday Luncheon Group also worked our connections in the department to get the Secretary to approve the program.

FSJ: As a longtime AFSA member, do you think the association’s role has changed? What would you recommend AFSA focus on today?

EJP: I joined AFSA a couple years after joining the Foreign Service. I think AFSA is still going strong, but I don’t think it is working on all the issues that it should focus on. I don’t think AFSA pays enough attention to minorities. It should seek minority input to better guide the Foreign Service toward an adequate representation of the entire United States.

AFSA needs to see itself as both a community activist and as an element of change. It can use Foreign Service officers from these communities to get things done, just as we did.

President Bill Clinton and Secretary of State Warren Christopher, center, talk with U.S. Ambassador to Australia Edward J. Perkins during a luncheon for Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating in Washington, D.C., in September 1993.

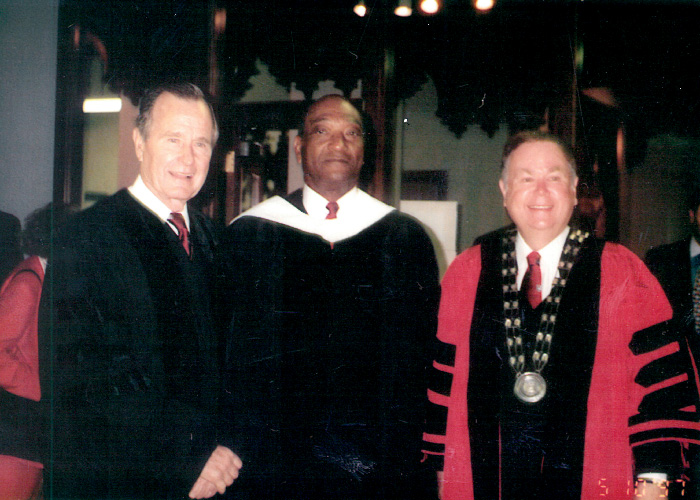

On Graduation Day at the University of Oklahoma, May 1997, Ambassador Edward J. Perkins, center, then director of the International Programs Center at the university, with former President George H.W. Bush, at left, and University of Oklahoma President David Boren. President Bush gave the commencement address.

Life After the FS

FSJ: After retiring from the Foreign Service in 1996, you became chair and executive director of the International Programs Center at the University of Oklahoma in Norman, and stayed until 2010. Can you tell us about your work there?

EJP: The center had been established by David Boren, then president of the University of Oklahoma, to develop a foreign policy studies program. I was its first director, and I was given a free hand and an academic and supporting staff. The goal was twofold: first, to create a strong and degreed approach to include foreign affairs within the university’s academic program; and second, to sponsor foreign affairs events at the university during the school year. I also taught graduate seminars on international relations.

The first foreign affairs event—“Preparing America’s Foreign Policy for the 21st Century,” in September 1997—was a huge success and put the university and Oklahoma on the map. I received a large number of congratulations at the dinner on the last night of the event from Oklahomans and university staff who did not believe we could bring foreign relations giants such as Henry Kissinger to the campus. It was a lot of work, but it paid off.

While at O.U., I established an international affairs curriculum that metamorphosed into the College of International Relations.

FSJ: What inspired you to write your memoir, Mr. Ambassador: Warrior for Peace?

EJP: I wanted to tell the story about the things that I overcame and accomplished that made me a successful Foreign Service officer. I tried to address the major events in my life and share the things that I have done to educate myself in preparation to meet the challenges in a long career. I also wanted to acknowledge the people—family, friends and professional colleagues, especially my late wife—who played a great role in my life.

The Foreign Service Career

Ambassador Perkins and U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan meet on March 15, 1999.

FSJ: You were ambassador four times, a great accomplishment. Any secrets to your success you can share?

EJP: Knowing oneself is very important. Eastern philosophy has also been the key to my success. When I first came across the Bushido code, which is a way of understanding oneself, and the writings of Sun Tzu and Miyamoto Musashi, I took the elements that would help make a difference in my life. These elements helped me get up in the morning, prosper in my work and go to bed peacefully at night. I return to these works often; they have always helped me understand my place in the universe.

FSJ: How successful have the State Department and the Foreign Service been in increasing diversity and inclusion?

EJP: The State Department and the Foreign Service have been partially successful; not nearly enough has been done. It shouldn’t be the responsibility of one office (management), but of the entire department and both Foreign Service and Civil Service communities. We represent all elements of this nation wherever we go, and we need to make sure all elements of the United States are also represented overseas.

FSJ: What advice would you give foreign affairs agencies on how to retain diplomats of color once they are in the Foreign Service?

EJP: Every effort should be made to ensure that diplomats of color become part of the Foreign Service family, part of the Foreign Service as a whole. We bring diplomats of color into the Service to fill a void needed to represent and support the mission; if this void isn’t filled, then the mission isn’t being fulfilled. We need to be “whole” to successfully carry out the words and the meaning of the Constitution and the Foreign Service Acts of 1924, 1946 and 1980.

FSJ: What are the essential ingredients for a successful diplomat?

EJP: Know yourself, and make sure that you keep yourself open to learning about the outside world and its communities while applying yourself to new situations. And do it often.

FSJ: What would be your advice to college students and recent graduates seeking to enter the Foreign Service or government service generally?

EJP: First is to recognize that we have a government that did not spring from the head of Zeus, but was created and developed through trial and error, ultimately with the goal of promoting a better way of life. My advice is to know why you want to join, and continually educate yourself on the evolution of our constitutional system and why the Foreign Service was created to promote our interests abroad. You also need to read and educate yourselves on how to be effective in this changing world.

FSJ: Are you optimistic about the future of professional diplomacy?

EJP: Yes, I am optimistic—probably more so now than ever before. The system of communication has improved drastically, making it easier now to send cables, guidance memos and reporting from the field than when I began in the Foreign Service. The ease of communication also makes it more dangerous to miscommunicate, so you must think of what the message is and why you want to convey it before you send it because messages reach a wider audience than before. We have an increasingly qualified corps of officers who are ready to go into the world and represent all of the people behind the Constitution of the United States.

Read More...

- “A Rich Life,” book review by Herman J. Cohen, The Foreign Service Journal, July-August 2006

- “A Black Ambassador to Apartheid South Africa,” Juan Williams, NPR, October 24, 2006

- “Ambassador Perkins’ Prayer,” The New York Times, April 15, 1987