Social Entrepreneurship and the Professional Diplomat

As international geopolitical dynamics become more complex, the scope has increased for “Track II” diplomacy—work to which former members of the Foreign Service are generally well suited.

BY JOHN MARKS

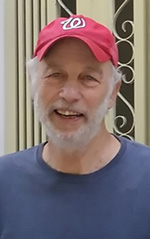

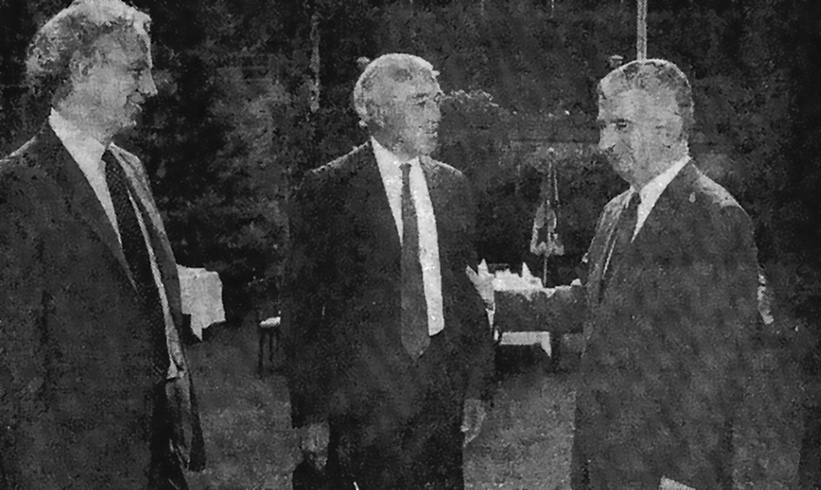

From left: John Marks, Ambassador Robert Frowick, and Macedonian President Kiro Gligorov in 1993.

Courtesy of John Marks

Diplomacy between nations has always been accompanied by unofficial gatherings, consultations, and discussions. During the past several decades, as international affairs and foreign policy challenges have become more complex and the activity of a variety of nonstate actors more widespread and significant, such “Track II” diplomacy has come into its own. Today nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) work unofficially around the world on a variety of issues to promote positive social change, including finding the basis for viable official solutions to problems ranging from trade disputes to civil war.

Track II ventures are often begun by social entrepreneurs. These are people who are skilled at launching endeavors aimed at promoting positive change in their community and the world. Their bottom line is not financial profit but the common good.

The nonprofit organization I founded in 1982, Search for Common Ground (commonly known as “Search”), made extensive use of the methodology of social entrepreneurship. Our vision at Search was large: we aimed to transform how the world deals with conflict—moving away from adversarial, win-lose approaches and toward nonadversarial, win-win problem-solving. The goal was to defuse or prevent violent conflict.

Begun as an effort to improve U.S.-Soviet relations, our first major project was to promote superpower cooperation against terrorism. After the fall of the Soviet Union, we grew steadily, branching out to other regions and addressing other issues. In 1991 we began working on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and in 1995 we established our first full country program in Africa, in Burundi. When I stepped down as president of the organization in 2014, we had a staff of 600 full-time employees at work in 35 countries. In 2018 Search for Common Ground was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. We had become the world’s largest peacebuilding nonprofit, and our toolbox included everything from traditional negotiation and mediation to production of TV soap operas and retraining more than 100,000 Congolese soldiers and conducting training to prevent sexual assault by soldiers.

The world would almost certainly be a better place if there were less need for our services. However, I was convinced, and still am, that peace is possible, and that even the most intractable conflicts can be resolved without violence.

From early on, I found that retired career diplomats and former ambassadors could be very useful in carrying out this kind of work, and our relationship with the U.S. Foreign Service has been important. Certainly, the diplomats have had to be comfortable operating in a milieu where advancing U.S. foreign policy was not necessarily the goal but where resolving conflict was. And moving from a world of protocol and démarches to a free-flowing organization like Search usually required major leaps of faith.

Our engagement with the Foreign Service and former ambassadors began in 1991, when I received a phone call, out of the blue, from retired Senior FSO Alfred “Roy” Atherton Jr., a former ambassador to Egypt and assistant secretary of State for Near Eastern affairs. He had heard about Search’s work and wanted to become involved. We had never before had such a high-level volunteer, and Atherton became the chair of our Middle East Advisory Board. With the assistance of other retired FSOs and former ambassadors, Search’s Middle East projects developed. And when Atherton passed away in 2002, retired FSO and longtime ambassador to Israel Samuel “Sam” Lewis replaced him as head of Search’s Mideast board.

Over the decades our engagement with career diplomats has continued; here are two examples of successful collaboration.

Macedonia’s “Lafayette”

In 1992, Robert “Bob” Frowick had been about to retire from the U.S. Foreign Service when Acting Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger personally asked him to take on an unorthodox position as the U.S. government’s unofficial envoy to Macedonia, which had just become a separate country and was not yet officially recognized. Seconded to the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) and sent to Skopje, Frowick lacked the amenities that a U.S. ambassador normally receives. Still, he was the highest-ranked foreign official in Macedonia, and he became, in effect, the Western proconsul who worked closely with President Kiro Gligorov. (Later, I described him as “Macedonia’s Lafayette”—that is to say, the foreigner who had the greatest impact in securing a new country’s independence.)

After six months, Frowick went home to what he thought would be a peaceful retirement. A few months later, I offered him the job as Search’s country director in Skopje, and, somewhat to my surprise, he accepted. His goal was “to keep Macedonia from exploding” due to ethnic and religious conflict. Search gave him a platform from which he could strengthen the country’s immune system. He brought his stature as a senior diplomat, and he projected impeccability. In the steamy Macedonian summer, he usually wore white linen suits, which might have been designed by Halston, the famous fashionista who happened to be his brother.

As Search’s man in Skopje, he remade the connections he had formed earlier in his days with CSCE, including his close relationship with President Gligorov, who became a strong supporter of Search. In those days, we were still a tiny organization, and having the backing of the president certainly helped us.

Search was a critical player in what was a three-legged effort to prevent violence. The components were a small United Nations military peacekeeping force, governmental foreign aid programs, and NGO activities like ours. Our role under Frowick and his successors was to carry out projects to promote tolerance and mutual understanding, and we did this by working closely with the press, by producing extensive TV programming, and by revamping early childhood education.

As significant as our work was, ultimately the most important reason the country did not explode probably was that Macedonians were fully aware of the appalling violence in nearby Bosnia, and most people—no matter what their ethnicity—did not want their country to suffer the same fate.

After the agreement with Iran on its nuclear program, the JCPOA, was signed in 2015, from left: Marvin Miller, nuclear scientist; Olli Heinonen, former deputy director, International Atomic Energy Association; Frank von Hippel, Princeton University physicist; Ali Akbar Salehi, former head of Iranian Atomic Energy Organization; Rush Holt, former U.S. Congressman and a physicist; and Ambassador (ret.) Bill Miller, members of Search’s nuclear group.

Courtesy of John Marks

Initiative on Iran

Search’s role in the decade-long lead-up to the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the agreement between Iran and the P5+1 (U.S., U.K., France, Russia, China, and Germany) on the Iranian nuclear program, also points to the value of career diplomats in Track II work.

William G. “Bill” Miller, who joined the Foreign Service in 1959 and resigned in 1967 over policy differences, spent five years in Iran as a young FSO. After Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini seized power in 1979, President Jimmy Carter asked Miller to be ambassador to Iran. Before he could be confirmed, militant students seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran. Miller never took up the post, and he was very involved in negotiations to free the hostages. After 444 days, the hostages were finally released, but diplomatic relations never resumed.

Fast forward nearly 20 years. In 1998, after serving as U.S. ambassador to Ukraine, Miller joined Search to work on our initiative to improve U.S.-Iranian relations, something he could not have done from inside the government. Ever the optimist, Miller believed that at some future time Iran and the United States would start talking about the most critical issue that separated them: namely, Iran’s nuclear posture. He reasoned that for negotiations to be successful, the two countries would need to find mutually acceptable solutions to technical issues, and he thought that Search could provide an unofficial forum in which experts from both countries could start that process.

In 2005 Miller convened a group that included a United Nations nuclear inspector, Iran’s former chief negotiator on nuclear matters, a hydrogen bomb designer, and several others with similar credentials. The group focused on providing impartial analysis and creative problem-solving. Miller kept White House and State Department officials informed, and they privately urged him to continue. We at Search became prime interlocutors between the U.S. and Iran because the two governments were not connecting in any meaningful way.

Over the next two years, our nuclear group met on six occasions with Javad Zarif, then Iran’s ambassador to the UN. Zarif later became foreign minister, and he personally negotiated the eventual nuclear agreement. Miller also met privately with Zarif about once a month. Here is what Zarif had to say about our involvement during this period: “I believe you saved our negotiations. … Without the work of the group, I believe discussions would have ended. … If there is any outcome of the negotiations that is to the satisfaction of both sides, it will be a derivative of the discussions of this group.”

Just after President Barack Obama was inaugurated in 2009, Miller arranged for and then attended confidential meetings in Europe and New York between former U.S. Secretary of Defense William Perry and Ali Akbar Salehi, head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization. Both men had access to top-level policymakers. We never learned what Salehi told Iranian leaders, but we knew that Perry personally reported to Obama that agreements on nuclear issues were possible. Miller believed that this was a critical step in moving the two countries into negotiations.

When official talks finally got underway, members of the Search group collaborated on detailed technical papers on how to overcome obstacles. Particularly important was a plan co-authored by three participants—Frank von Hippel, Hossein Mousavian, and Alex Glaser—to redesign the Arak heavy water reactor into a device with far less yield of plutonium and to convert 20 percent enriched uranium into fuel plates. This paper provided the basis for eventually resolving the issue. As Foreign Minister Zarif said in 2016: “I have used what I learned from you when we last met in the negotiations, particularly on conversion of the fuel to oxide form, the limit of the number of centrifuges, and conversion of the Arak reactor. … You can claim parenthood in this endeavor. Thank you for putting the road in place for us to follow.”

Zarif’s American negotiating partner, Secretary of State John Kerry, similarly stated in a 2017 interview: “During the Iran talks, the fresh ideas you provided helped us to achieve a breakthrough on the Arak heavy water reactor.”

By establishing a credible forum to examine nuclear issues in a mutually respectful manner, Search provided a testing ground for innovative ideas and helped to build trust, which was necessary for eventual negotiations to succeed. Despite our disappointment at the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018, we still were pleased to have contributed as much as we had. We had proved to be ahead of the curve. As Track II diplomats, we had fulfilled our mission of complementing, supplementing, and sometimes anticipating official policy decisions with the invaluable assistance of retired career members of the U.S. Foreign Service, professional diplomatic practitioners.

§

§

In the turbulent and fast-changing world of the 21st century, the need for unofficial diplomacy and effective social entrepreneurship can only grow. Senior-level diplomats casting about for meaningful ways to put their skills to use in a follow-on career would be wise to take note.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “From Diplomat to Dissident” by John Marks, The Foreign Service Journal, April 2000

- “Teaching Diplomacy as a Process (Not Event): A Practitioner’s Song” by Barbara K. Bodine, The Foreign Service Journal, January-February 2015

- “The Business of Peace-Building,” WNYC: The Brian Leherer Show Segment with John Marks, October 2024