AFSA’s First Hundred Years

Entering its second century, the professional association and bargaining agent for the U.S. Foreign Service is stronger than ever.

BY HARRY W. KOPP

At its inception in 1924, the American Foreign Service Association was a small, quiet club dedicated to fellowship, good works, and professional improvement. One hundred years later, AFSA is a large and often noisy organization that shapes and protects the U.S. Foreign Service while enhancing the lives and careers of its members. AFSA’s story of growth and transformation is a tale worth telling and—or so this writer hopes—a tale worth reading too.

The Early Years: 1924-1940

John Jacob Rogers, the “father of the Foreign Service,” was a Republican congressman from Massachusetts. Born in Lowell, Mass., in 1881, he was first elected to the House of Representatives in 1912. After a brief stint in late 1918 as a private in the Field Artillery, Rogers introduced a series of Foreign Service reform bills, drafted largely by Wilbur Carr. He finally won passage in May 1924 of the act that bears his name. Less than a year later, he was dead.

His wife, Edith Nourse Rogers, succeeded him in Congress. She worked for passage of the Moses-Linthicum Act and was a key sponsor of bills creating the Women’s Army Corps, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, and the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the GI Bill. Rep. Nourse Rogers served in Congress for 35 years until her death in 1960.

Library of Congress

In the early years of the 20th century, the U.S. consular service—the greater part by far of the country’s official overseas representation—emerged from a long history of patronage and incompetence. A growing sense of pride in their work and their institution led a group of consular officers in 1918 and 1919 to form the American Consular Association and publish a monthly American Consular Bulletin, “an organ by which information of interest to the Service might be disseminated.” As soon as the Foreign Service Act of 1924 merged the consular and diplomatic services, the consuls invited members of the smaller (and, it must be said, snootier) diplomatic service to join their organization.

The American Foreign Service Association took shape that August. The new association, called AFSA from the beginning, was open to “all career officers of the American Foreign Service.” It was to be “an unofficial and voluntary association” formed to foster “esprit de corps … and to establish a center around which might be grouped the united efforts of its members for the improvement of the Service.” The American Foreign Service Journal replaced the American Consular Bulletin with no gap in publication.

In the period immediately following passage of the Foreign Service Act of 1924, the Service saw itself as the State Department’s creation, its ward. That the two institutions might have different or conflicting interests was unthinkable and unthought. The association had no interest in conflict. The Journal’s masthead carried this statement: “Propaganda and articles of a tendentious nature, especially such as might be aimed to influence legislative, executive, or administrative action … are rigidly excluded.”

The appeal of the association lay in forming and maintaining connections among the scattered members of the Foreign Service, 90 percent of whom were overseas. Much space in the Journal was devoted to lists of transfers, promotions, appointments, weddings, births, and deaths, along with occasional social trivia. (“Consul Tracy Lay recently motored to the Berkshires. He caught some good fish.”)

But the absence of conflict did not exclude good works. Three early AFSA initiatives—the scholarship fund, the insurance program, and the memorial plaques—have had a lasting impact.

• In 1926, Elizabeth Harriman (spouse of a cousin of future diplomat W. Averell Harriman) gave AFSA $25,000 to establish a scholarship fund in honor of her late son, a Foreign Service officer who died while on duty overseas. In 2022 the fund awarded $263,000 in need-based financial aid to 74 students, and $143,000 in merit awards to 38 students.

• Also in 1926, AFSA and the Equitable Life Insurance Company of New York set up the American Foreign Service Protective Association (AFSPA) to contract with underwriters to offer AFSA members group health, life, and accident insurance. Today, AFSPA, with a board of active or retired members of the Foreign Service and other executive agencies, insures more than 87,000 active-duty and retired civilian employees of the Departments of State and Defense and members of the Civil Service with an overseas mission, regardless of agency. The Senior Living Foundation, established by AFSPA in 1988, assists Foreign Service retirees confronting the problems of old age.

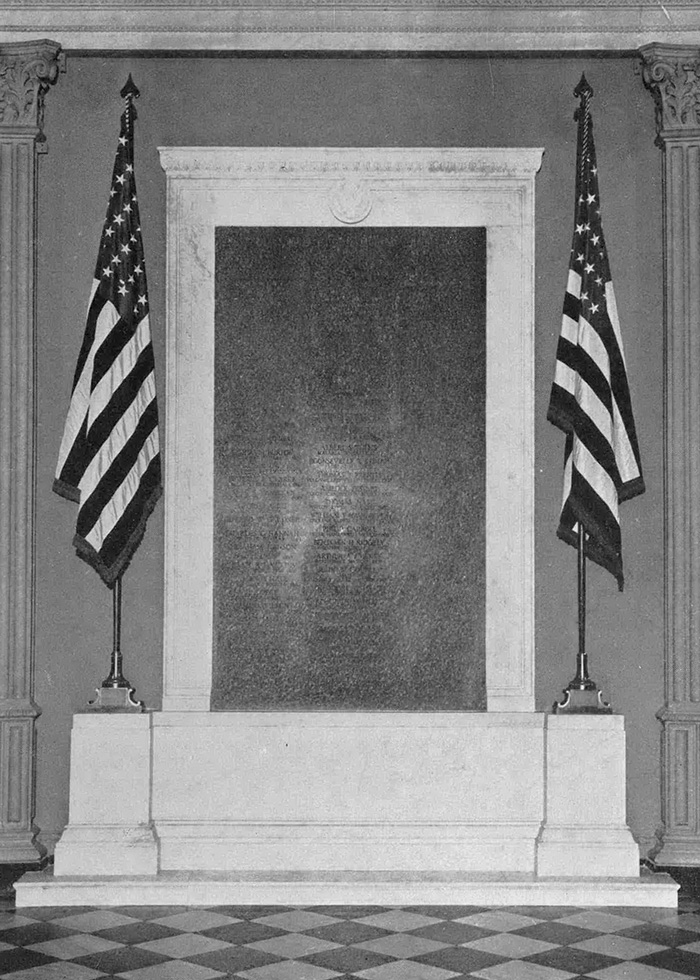

• In 1929, at the urging of one of its members, AFSA began to put together an “honor roll” of “those in the American Foreign Service who, since the earliest days of our national existence, have died under tragic or heroic circumstances.” Sixty-five names were inscribed on a plaque that Secretary of State Henry Stimson unveiled in the lobby of the State, War, and Navy Building on March 3, 1933, the last day of Herbert Hoover’s presidency. Today, there are 321 names on the memorial plaques at Main State.

Growth and Conformity: 1941-1967

The cover for the December 1924 American Foreign Service Journal, a photograph contributed by Under Secretary of State Ambassador J.C. Grew. In 1924 the American Consular Bulletin became The American Foreign Service Journal.

FSJ Digital Archive

Like other Americans born in 1924, AFSA and the Foreign Service grew up fast in the years after Pearl Harbor. The career Service numbered 840 in 1940; 10 years later, the count was 7,610. Much of the growth came through the Foreign Service Act of 1946, which brought thousands of non-career employees—clerks, secretaries, couriers, certain vice consuls—into a career Foreign Service staff corps and hundreds of “technical specialists,” most of them wartime hires, into a Foreign Service reserve corps for officers on time-limited commissions.

AFSA abandoned its passivity to take part through its executive committee in the drafting of the act, which established unique rules for the Foreign Service on hiring, assignment, promotion, pay, dismissal, and retirement. The act sharpened differences between the Civil Service and Foreign Service.

In the years after World War II, anti-communist and anti-gay fervor seized much of the country: it seemed the moral exaltation of wartime could not be demobilized but had to find a new mission. Congress gave the Secretary of State “absolute discretion” to fire any employee deemed a “security risk,” a term the department defined to include people with “sexual peculiarities, alcoholism, or … an indiscreet and chronically wagging tongue; [regardless] of the individual’s loyalty to this country.” Between 1947 and 1952, constantly goaded by Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisc.) and his allies, the department fired more than 600 employees. An unknown number of others simply resigned.

In the face of these shocks and humiliations, AFSA, with a few courageous exceptions, was silent. By the end of the decade, AFSA was an afterthought, “an effete club of elderly gentlemen whose headquarters could not be located and who took care never to fight for any cause,” in the words of an AFSA member. This harsh judgment was only half true: AFSA’s headquarters could in fact be located, in a couple of rented rooms on G Street Northwest.

Transformation: 1967-1983

On March 3, 1933, President Herbert Hoover’s last day in office, Secretary of State (and AFSA honorary president) Henry L. Stimson stood next to AFSA Chairman Homer L. Byington and unveiled this tablet in the lobby of the State, War, and Navy Building. Inscribed on the tablet were the names of 65 “diplomatic and consular officers of the United States who while on active duty lost their lives under tragic or heroic circumstances.” As of January 2024, there are 321 names on AFSA’s memorial plaques in the lobby of Main State.

FSJ Digital Archive (June 1933 Edition)

As the gray-flannel 1950s gave way to the tie-dyed 1960s, the spirit of dissent and rebelliousness that spread across the country came to affect the staid Foreign Service. A group of mostly young, reform-minded officers chafed at their lack of influence and came to realize that AFSA could become a vehicle for change. AFSA, they said, “can and should be heard” on matters of personnel, leave, transfers, health benefits, and the like. The message resonated. Led by mid-level officers Lannon Walker and Charles Bray, the reformers won all 18 seats on the electoral college that, under AFSA’s odd rules, chose a board of directors that then chose its own chairman and officers. On Oct. 1, 1967, control of AFSA passed into the reformers’ hands.

The reformers, called the “Young Turks” after the Ottoman revolutionaries of the early 20th century, brought new ideas and new energy. They replaced the electoral college with direct elections. They testified on the Hill. They raised money: funds from John D. Rockefeller III and the Harriman, Rivkin, and Herter families let Charlie Bray devote full time to AFSA on leave without pay, financed publication of the reform manifesto Toward a Modern Diplomacy, and launched the AFSA awards program, including the awards for constructive dissent that after more than 50 years remain unique in the government. Bray and AFSA Vice President John Reinhardt went to the 1968 Republican convention and secured a statement in the party’s platform: “We strongly support the Foreign Service and will strengthen it by improving its efficiency and administration and providing adequate allowances for its personnel.” Nothing remotely like that had happened before.

The State Department was hostile. Soon after Walker took office as chairman of AFSA’s board, the department’s top management official, Idar Rimestad, called him in and told him: “Just who the [expletive] do you think you are? You don’t represent anybody, and you’re not going to get anything.” AFSA responded with an open meeting that packed the department’s auditorium with a noisy and approving crowd. The era of passive deference was over.

The department’s refusal to work with AFSA impelled the association to transform itself into a labor union with which management would be compelled to deal. There were new players—William Macomber took over as chief management officer at State; Bill Harrop, Tom Boyatt, Tex Harris, and Hank Cohen formed the leadership at AFSA—and a White House open to change in employee-management relations across the federal government.

AFSA’s leadership had to find a path between those in the membership who believed that commissioned officers should join no union and those (the greater number) who would reject AFSA in favor of AFGE—the American Federation of Government Employees, a “real” union with a reputation for militancy. AFGE believed in equal pay for equal work, a concept incompatible with rank-in-person, and held that “Foreign Service personnel should be treated at home as domestic civil servants.”

On Oct. 1, 1967, control of AFSA passed into the reformers’ hands.

Whether AFGE or AFSA would become the exclusive employee representative—the union—for the Foreign Service would be decided by elections in each agency. AFSA’s leadership joined with Bill Macomber at State to persuade the White House to set election rules incorporating a broad franchise that worked in AFSA’s favor. Board member Tom Boyatt guided AFSA’s multiple campaigns, which through many legal twists and turns ended in 1973 with victories over AFGE at State, the U.S. Information Agency (USIA, established 1953), and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID, established 1961). First- and third-person accounts of these transformative battles appear in the Journal editions of June 2003, April 2013, and January-February 2023, on the 30th, 40th, and 50th anniversaries of the events, respectively. [All editions can be found online at https://afsa.org/fsj-archive.]

AFSA president Tom Boyatt (second from left) testified on the State Department Appropriations Authorization Act before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on March 12, 1974. With him are (from left) AFSA Vice President Tex Harris, AFSA Treasurer Lois Roth, and Hank Cohen, chairman of AFSA’s members’ interests committee. Boyatt led off with an attack on the sale of ambassadorships to campaign contributors. Boyatt, later ambassador to Burkina Faso and Colombia, and Harris (AFSA president 1993-1997) were elected to positions on AFSA’s Governing Board again and again into the 2010s. Boyatt received AFSA’s award for lifetime contributions to American diplomacy in 2008. Cohen, who retired in 1993 with the rank of Career Ambassador, received the same award in 2019.

FSJ Digital Archive (June 1974 Edition)

The Path to the Act of 1980. Boyatt, forceful and feisty, became AFSA’s first directly elected president in 1974. He was a vigorous defender of dissent (and was himself a notable dissenter, over U.S. policy in Cyprus). He and Bill Harrop testified in the Senate against the confirmation of egregiously unqualified political appointees. He defended the American embassy in Santiago, under attack in the media and Congress for its performance during the coup that toppled President Salvador Allende. “We will never again,” he said, “permit McCarthyism or any other threat to impinge upon our integrity or to silence our dedication to the national interest.”

Ambassador Carol Laise, Director General (DG) of the Foreign Service from 1975 to 1977, found that her role had changed: “Tom Boyatt made it very clear to me that [AFSA] represented the Foreign Service on policy issues with management,” she said. With unionization and the rise of AFSA, the DG no longer had a constituency.

Backlash. Maybe AFSA’s many achievements—extending the education allowance to kindergarten; overtime pay for secretaries, communicators, and other staff; protection of selection-board recommendations from political interference—had come too easily. Many rank-and-file members remained dissatisfied and eager for confrontation with management. Their dissatisfaction erupted in a three-way contest for the presidency in 1975, narrowly won by John Hemenway, a civilian employee at the Department of Defense who had been dismissed from the Service under time-in-class rules in 1969. Hemenway was imperious and vindictive. He testified against promotions for a number of career officers he disliked and ignored the rebukes of a furious board. The board launched a recall movement, and a chastened membership removed him from office on Nov. 17, 1976, by a vote of 2,751 to 175.

The desire for confrontation was strongest at USIA, where Hemenway had his best showing. Soon after Hemenway’s ouster, AFGE forced and won a new representation election at the agency, which it won by a vote of 853 to 504. AFGE remained the union for the Foreign Service in USIA from 1975 until 1992, when another representation election restored AFSA to that role. AFSA would never again lose a representation election.

As the gray-flannel 1950s gave way to the tie-dyed 1960s, the spirit of dissent and rebelliousness that spread across the country came to affect the staid Foreign Service.

The Foreign Service Act of 1980. The administration of President Jimmy Carter (1977-1981) had a fascination with the machinery of government. Carter sought and won the creation of two new cabinet departments (Education and Energy) and shuffled boxes at State, USIA, Commerce, and USAID. He won passage of the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978, which set the stage for the Foreign Service Act of 1980.

AFSA negotiated with State management and directly with Congress on the act’s main provisions—clear separation of the Foreign Service and the Civil Service, with a separate Foreign Service retirement system; merger of the Foreign Service staff corps (whose members came to be known as specialists) with the officer corps on a single pay scale; and codification of procedures for resolving personnel grievances and labor-management disputes. As AFSA and the department had urged, the act made the Foreign Service system available to other agencies—the Departments of Agriculture and Commerce chose to use it for the Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) and the new Foreign Commercial Service (FCS), both of which voted in 1994 to have AFSA as their union. For AFSA members, the act’s most popular feature was a substantial increase in pay and benefits; least popular were new time-in-class and time-in-service rules linked to the creation of the Senior Foreign Service, with mandatory retirement at age 65.

In the months following passage, AFSA negotiated with management on implementation, a new process for both sides. Discussions covered the relationship of the Foreign Service and the Civil Service, protection of merit principles, the role of the chief of mission, performance evaluations and promotions, training, incentives, medical care, selection out, separation for cause, and retirement. As resources allowed, AFSA hired more staff to provide guidance to members on agency regulations. At the same time, the association remained a professional society, the defender of career and merit principles against political assault.

Ambassadors. The 1980 act said that political contributions should not be a factor in appointments of chiefs of mission, which should “normally” go to career officers. AFSA in public testimony squeezed these provisions for all that they were worth, which turned out to be not much. In 2014 AFSA won legislation to force access to the statements of “demonstrated competence” the act requires the department to send to the Senate with respect to each nominee. Despite these and other efforts, political appointees continue to occupy around 40 percent of ambassadorial posts, and large donors continue to be rewarded with cushy embassies. Public attention to this has had little to no impact on the practice.

1983-2001: Austerity and Diversity

In September 1987, Secretary of State George P. Shultz told a crowded open meeting in the Acheson auditorium: “We’re being brutalized in the budget process.” The brutality had just begun. The Foreign Service, which had numbered about 9,200 officers and specialists in 1988, shrank to about 7,700 10 years later. Over the same period, State’s Civil Service rolls rose by more than 6 percent, to almost 5,000.

Cuts in the Foreign Service tested AFSA’s shaky commitment to diversity. The 1980 act called for a Service “representative of the American people,” operating on “merit principles” and employing “affirmative action programs” to promote “equal opportunity and fair and equitable treatment” without regard to “political affiliation, race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, age, or handicapping condition.”

Because the Service was disproportionately white and male, the dismissals in the 1990s fell largely (though by no means solely) on that group. AFSA went on record opposing “measures that would bestow special advantages not equally available to all members of the Foreign Service” on members of “an EEO [equal employment opportunity] category.” The head of the Merit Systems Protection Board in State’s Office of Policy and Evaluation said: “A lot of white males are discriminated against,” and an unknown number of AFSA members shared that sentiment.

The Foreign Service, which had numbered about 9,200 officers and specialists in 1988, shrank to about 7,700 10 years later.

Neither the Foreign Service Act of 1980 nor the department’s affirmative action programs seemed to have much effect. What did work, at least to some degree, was litigation. First female and later Black officers filed class-action suits that led to hundreds of retroactive promotions and court-ordered changes in the hiring process. AFSA, internally divided, chose not to be a party to the lawsuits.

After the 2020 murder of George Floyd and the mass demonstrations that followed, AFSA abandoned its hesitation and gave full-throated support to greater diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility. AFSA’s negotiating positions on issues related to hiring, promotion, performance evaluation, and assignment reflected this change of heart. But AFSA can negotiate only on process and procedure, with limited influence on outcomes. In 2022, according to AFSA President Eric Rubin (2019-2023), the Senior Foreign Service was “the least diverse it’s been in more than 30 years”—two-thirds male and 80 percent white. In the end, as AFSA President Hume Horan (1991-1992) said, “We Americans deserve a Foreign Service that is excellent and representative, and it is management’s job to see that we get it.”

Goodbye, USIA. The austerity drive of the 1990s was wind in the sails for a measure long favored by Sen. Jesse Helms (R.-N.C.), chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, to close USIA, USAID, and the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA), and transfer their functions to the State Department. AFSA initially opposed the bill, but after Bill Harrop and Tom Boyatt rejoined the board in 1995 as retiree representatives, the board was split, with Harrop and Boyatt in favor of the bill and Tex Harris opposed. AFSA took no position, the bill was passed, vetoed, amended, and passed again, this time with USAID spared the ax. In that form President Bill Clinton signed it into law in 1999. USIA was shuttered with AFSA absent from the fight.

Susan Johnson, in her role as AFSA president, addresses the crowd at the “Rally to Serve America” in April 2011 in Washington, D.C., a demonstration she led in support of the professional integrity of foreign affairs agency personnel.

AFSA / Donna Ayerst

2001-2009: AFSA at War

By the time Colin Powell took office as Secretary of State (2001-2005), the Service had lost some of its attraction. More than 700 Foreign Service positions were vacant. Powell’s prestige as a former national security adviser, a former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the first Black Secretary of State helped him win the funding needed to repair some of the damage. A surge in candidacies after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, added 2,000 members to the Service by 2005.

AFSA, too, grew stronger as the new century began. The membership approved a raise in dues sufficient to pay for capital improvements, higher staff salaries, and an increase in reserves, which were placed under professional management. Between 1997 and 2002, unrestricted reserves rose from $270,000 to more than $1 million.

The 2001 election put John Naland at the head of a board that included four former AFSA presidents—Tom Boyatt, Tex Harris, Bill Harrop, and Ted Wilkinson. Naland, who had served as State vice president, continues to be a near-constant presence on the board. He saw AFSA’s union and professional sides as tightly linked: “If a future ‘reform’ ever eliminates the features that make us unique,” he said, “we will inevitably lose the benefits that flow from that uniqueness.” (Naland will be writing about some of AFSA’s many accomplishments and how they shaped the Service in the Journal during this centennial year.)

On Sept. 11, 2001, Naland and many of his board were on Capitol Hill, urging Congress to fully fund the international affairs budget, when news arrived of the attacks in New York and at the Pentagon. The attacks reinforced AFSA’s message on the Hill, that the country needed a stronger, better-resourced, more professional Foreign Service; and Congress was briefly receptive.

Then the scapegoating began. The U.S. embassy in Saudi Arabia had issued visas to 15 of the 20 hijackers; many in Congress sought to move the visa function from State to the new Department of Homeland Security, then under hasty construction. AFSA lobbied in defense of State’s traditional role and defended the consular bureau. Naland met with House staff, pointing out that intelligence agencies had withheld, and continued to withhold, information that could change a consular officer’s decision. But it was a hard case to make. The staffing cuts of the 1990s had left vacancies unevenly distributed, with larger gaps in hardship posts than in more comfortable places. Blame-seekers in the White House, Congress, and the media used that fact to support their claims that the Department of State was full of incompetents and the Foreign Service full of wimps.

The department’s refusal to work with AFSA impelled the association to transform itself into a labor union with which management would be compelled to deal.

AFSA worked to change opinion in Congress and the public. AFSA speakers fanned out around the country. Tom Boyatt organized AFSA-PAC, a political action committee whose (quite modest) donations, equally distributed among Republicans and Democrats, bought access to lawmakers for AFSA’s leadership. The Foreign Affairs Council, another Boyatt project, brought 11 civic organizations together in support of a strong U.S. Foreign Service. A relaunched AFSA Fund for American Diplomacy raised money for outreach. AFSA President John Limbert (2003-2005), whose experience as a hostage in Tehran in 1978-1981 gave him an extra measure of credibility, was a strong public presence (his mantra: “Let no cheap shot go unanswered”). Television coverage reached the broadcast networks as well as Fox News, Bloomberg News, CNN, PBS, NPR, and BBC. The energy resonated in the Service. Membership reached record levels in 2003.

The wars in Afghanistan and (especially) Iraq created new and severe problems. In 2005, two years after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, the U.S. began to deploy civilian-led Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) in Iraq to build “a capability in [local] governing bodies to deliver to the people” the services that governments are supposed to provide. Most PRTs were led by U.S. Foreign Service officers (a few were led by civilians from allied countries) and relied heavily on Foreign Service personnel. Posts worldwide were stripped of personnel to fill positions in Iraq. By 2007, more than 22 percent of all Foreign Service personnel, all volunteers, had served in Iraq or Afghanistan, and 21 percent of other Foreign Service positions, overseas and in the department, were vacant.

Yet staffing demands did not abate. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice (2005-2009) was prepared to use directed assignments—orders—to get people to go where she wanted them to go. AFSA pushed back. State Vice President Steve Kashkett said: “We are not the military. Telling us—single mothers, middle-aged guys with families, unarmed civilians with no military training—that we have to serve in a live-fire zone is not something we should ever be doing. … That was the position of the AFSA board.”

Ultimately, Secretary Rice wrote in her memoirs, “enough people volunteered. But I was prepared to face down the American Foreign Service Association—a kind of union for U.S. diplomats—before Congress and the American people.” That enough people volunteered was rarely acknowledged, and at the time the Secretary allowed attacks on the Service to go unanswered.

The AFSA board came to see the administration as hostile, and not just the political appointees. John Naland, who returned to AFSA’s presidency in 2007, accused some career officers of failing to stand up for the Service, acting as toadies to gain a plum assignment or a performance-pay bonus. “Have some senior career officials ‘sold their souls’ over Iraq and other issues in order to advance their careers? I believe they have,” he wrote.

In March 2019, Ambassador Barbara Stephenson, then AFSA’s president, spoke at The Foreign Service Journal centennial exhibit opening held in the U.S. Diplomacy Center (now the National Museum for American Diplomacy). This was also the launch of the FSJ Digital Archive, which houses 100-plus years of The Foreign Service Journal.

AFSA / Joaquin Sosa

2009-2017: The Obama Years

Soon after the administration of President Barack Obama took office, his Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton (2009-2013), announced a program to increase the size of the Foreign Service at State by 25 percent by the end of Fiscal Year 2013, and at USAID by 100 percent by the end of FY 2012. Yet a high level of vacancies remained at mid-level positions overseas, and senior officers were losing job opportunities to political appointees, causing a logjam that blocked promotions and increased forced retirements for time in class and time in service.

As it had in the 1940s and 1950s, AFSA fought against mid-level hiring, urging State and USAID to raise promotion rates, waive time-in-class limits, and take other measures to fill vacancies with Service members. AFSA President Susan Johnson (2009-2013) took the case for senior appointments public, in a Washington Post op-ed written with the American Academy of Diplomacy’s chairman and president, retired ambassadors Tom Pickering and Ron Neumann. In 1975, they wrote, FSOs occupied 12 of 18 positions at the level of assistant secretary of State or above. In 2013, there were 33 such positions, but FSOs held only eight. The proliferation of political appointees, they wrote, “spawns opportunism and political correctness … and emaciates institutional memory.” More controversially, they argued that the department’s Civil Service had grown “at the expense of the Foreign Service.”

For this latter claim, Johnson was attacked by a group of nine Senior Foreign Service officers and defended by several past presidents of AFSA, but the data was not in dispute. Although she had received the department’s Distinguished Honor Award and multiple Meritorious Honor Awards, she received no onward assignment and retired at the end of her second term.

2017-2023: The Trump Administration and Beyond

AFSA and its president, Barbara Stephenson (2015-2019), greeted the Trump administration (2017-2021) with a certain hopefulness. “You Can Count on Us,” Stephenson wrote in the January-February 2017 Foreign Service Journal. When Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (2017-2018) announced his intention to “redesign” the Department of State, she publicly hailed the potential. “I’m encouraging all of our folks to make the most of this opportunity for reform,” she said—despite a hiring freeze that showed no signs of ending and an administration budget request that would cut State and USAID by 30 percent.

And when Tillerson’s successor, CIA Director Mike Pompeo, declared, “I want the State Department to get its swagger back,” Stephenson felt a surge of optimism. Secretary of State Pompeo (2018-2021) lifted the hiring freeze and, as AFSA had demanded, restored the ability of overseas posts to hire spouses and other family members of employees on permanent assignment.

In fact, there was never any hope of a positive relationship with the administration, which from the campaign forward treated government professionals as political enemies and likely saboteurs. Political appointees at State harassed and vilified career professionals, without serious consequences. Especially at senior levels, resignations and early retirements came in droves (minister-counselors down from 431 to 369 between September and December 2017), leading Stephenson to write in “Time to Ask Why,” her December 2017 President’s Views column: “Where is the mandate to pull the Foreign Service team from the field and forfeit the game to our adversaries?” In 2019 the number of FSOs serving as assistant secretary or above fell to zero.

Stephenson chose to turn AFSA away from lobbying for benefits. She gave guidance to AFSA staff: “The point we need to make to Congress … is that we are chosen through an extraordinary process and make extraordinary sacrifices in the name of our country, and we do it willingly. Don’t talk about allowances, talk about how proud we are to serve.” These were words Congress needed to hear, at a time Congress needed to hear them. AFSA pounded the message home.

Amb. Marie Yovanovitch and then–AFSA President Eric Rubin discussed her new memoir on March 30, 2022, at AFSA headquarters. Rubin is holding up a copy of his review of Lessons from the Edge in the April 2022 FSJ.

AFSA / Julia Wohlers

Impeachment. Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch, a career FSO, faced hard choices. President Trump and Secretary Pompeo recalled her from Kyiv, where she was ambassador, because she was seen as an obstacle to Trump’s efforts to obtain a Ukrainian announcement of an investigation into the activities of former Vice President Joe Biden and his son Hunter, a board member at a Ukrainian energy company. A House committee of inquiry into what Democrats in Congress called the “Trump-Giuliani Ukraine scheme” to force that announcement by withholding military aid called on her to testify, under subpoena. The administration told her not to comply. She had to choose. The same choice faced other career Foreign Service members called by the committee: Ambassador Michael McKinley, David Holmes, Jennifer Williams, and George Kent.

Yovanovitch wrote in her memoir: “AFSA had been my first stop when I was recalled … and it had stood by me ever since. … AFSA told us that the administration would have a hard time disciplining or firing me if I testified. Most importantly, they assured me that my pension was safe.” She and the other FSOs subpoenaed chose to testify. (The choice infuriated Secretary Pompeo. He later wrote, falsely: “Yovanovitch was the quintessential example of a leftist, progressive, activist Foreign Service officer who behaved in ways that would have made our Founders cry.”)

AFSA President Eric Rubin (2019-2023) and the board felt the weight of history. “We knew,” Rubin said, “that we had failed to adequately support our members during the McCarthy period. … The feeling on the board was, this is a moment of testing; we’ve got to be worthy of it.”

More than moral support, AFSA offered money. A Legal Defense Fund had been set up in 2007; a public call for contributions raised $750,000 in three months, available to witnesses who were AFSA members. No AFSA member was out a single penny.

AFSA Forward. Many of the goals for which AFSA had fought, sometimes for years, were accomplished in a rush when the Trump administration left office—parental leave; in-state college tuition for Foreign Service members serving abroad; protections comparable to those afforded the military for Foreign Service members forced by transfer to break car leases, cell phone contracts, and the like; improvements in the government’s response to “anomalous health incidents” (Havana syndrome); and others. “The administration has been no help at all,” said Eric Rubin. “We do it ourselves on the Hill.”

Across all agencies, close to 80 percent of active-duty members of the Foreign Service belong to AFSA. Its finances are solid, with a budget of around $5.5 million. It owns its building, free of liens. AFSA is stronger now than it has ever been.

The question for AFSA’s leadership, and even more for AFSA’s membership, is how to bring that strength to bear to achieve the association’s goals: to promote the career Service as the institutional backbone of American diplomacy; to protect the rights and interests of its members; to maintain high professional standards for all American diplomats, career and non-career; and to be a strong advocate for the Foreign Service with agency management, the administration, Congress, and the public.

AFSA is the voice of the U.S. Foreign Service. It needs to be heard.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- AFSA History Special Collection, The Foreign Service Journal Digital Archive

- AFSA History Timeline, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2014

- “In the Beginning: The Rogers Act of 1924” by Jim Lamont and Larry Cohen, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2014

- “AFSA Becomes a Union: Why It Matters” by John K. Naland, The Foreign Service Journal, January 2023