Is American Diplomacy with China Dead?

China’s rise in a rapidly changing world presents a challenge that only strategic, patient, firm coalition diplomacy can meet successfully.

BY SUSAN A. THORNTON

How did we get to a place where the United States government, egged on by clickbaiting media and others, actively shuns talking as a way of solving problems? We need look no further than the wreckage of recently abandoned treaties and international agreements to understand that American diplomacy has indeed fallen on hard times. Whereas U.S. diplomats used to be relied on to prevent crises, to solve international problems, to devise new agreements, rules and institutions, they are now viewed by their own government with suspicion, and the word “global” has become an epithet.

Diplomats are trained to discern how the dynamics of other countries are different from our own; how, left to their own devices, they will affect our interests; and how we might shape or harness them to service our interests, or at least not harm them. This requires curiosity, patience, listening, persistence and, above all, a realistic analysis of our interests and where they diverge or overlap with others. If a convergence of interests cannot be found and exploited through persistent, low-cost diplomacy and persuasion, we must then assess what higher costs we are willing to bear to force our interests on another country, and whether that force will succeed or fail.

It is important here to make an accurate assessment of what other countries are likely to do to defend their interests in the face of U.S. coercion, which is another area where diplomatic expertise comes in handy. Because we should at least know what we’re getting ourselves into, right?

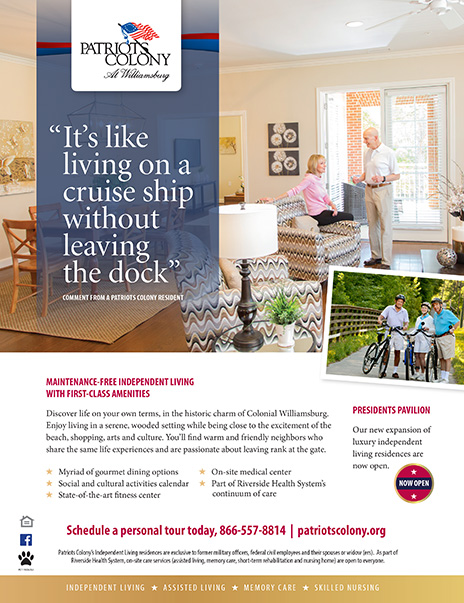

Susan Thornton with Ambassador Chas Freeman (left) and Professor Ezra Vogel at a conference marking the 40th anniversary of U.S.-China relations hosted by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing in December 2018.

Courtesy of Susan Thornton

Waning U.S. Influence in a Changing World

Susan Thornton on an April 2017 secretarial visit to China aboard a C17 that was being used because Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s plane had broken down.

Courtesy of Susan Thornton

The abandonment of U.S. diplomacy at this juncture is especially fraught. We are in the midst of a shift in the global power structure, while at the same time, technology and globalization are accelerating the pace of change in our world. American strategies for and responses to these changes will have long-term, indelible effects on the future of our country. We cannot hold back the change. Our future success will depend on our ability to coax (not coerce) cooperation from others, our ability to provide leadership and build coalitions to tackle transnational problems, our resilience in adapting to change and, most of all, our ability to set an example that others want to follow. We are currently deficient in each of these areas.

But nowhere are the effects of abandonment of U.S. diplomacy more evident or more consequential than in the ongoing U.S.-China meltdown. Some may protest and say that we are engaged in diplomacy with China. This is not serious. President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo have met more in the last year with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un than they have with their Chinese counterparts. Exchanges of “beautiful letters” are a poor substitute for real face-to-face discussions, and a narrow contest of wills over a trade dispute cannot substitute for the hands-on management of the serious challenges that plague U.S.-China relations.

The current “get tough” approach bears more resemblance to the antics of an overly cocky teenager than major power diplomacy. Administration officials refuse to meet Chinese counterparts, humiliate Chinese leaders with “tweet storms” and trash-talk Chinese initiatives and companies on the global stage. The FBI director names China a “whole-of-society threat,” and a high-ranking political appointee State Department official asserts that the United States is involved in a “clash of civilizations” with China “because Chinese are not Caucasians.”

U.S. military encroachments and surveillance missions close to Chinese territory spur a daily high-stakes game of cat and mouse, and U.S. officials assert publicly that Washington and Beijing are already in a “cyber war.” U.S. district attorneys travel the country to warn about talking shop to ethnic Chinese co-workers. Rafts of anti-China legislation spew from the printers of congressional staffers. And there are many other, more risky gambits being unspooled behind the black curtain. Even during the most hair-trigger days of the Cold War, the Soviet Union was not treated to such mindless and peripatetic hostility from the U.S. government.

Most countries, including China, do not formulate their national strategies—or think about their futures—through the prism of other countries.

“China deserves it,” we say. “They have behaved badly, stolen our property, sold us cheap goods.” “They aim to kick us out of the Pacific, undermine our alliances, displace the United States in the world.” “China breaks international conventions, incarcerates its ethnic minority populations and aims to export a model of authoritarian capitalism.” These are just some of the salient complaints—and there is no question that China’s rise poses real challenges, and its behavior presents real concerns.

The China Reality

China is the largest country by population in the world, containing one-fifth of humanity. It has the second-largest economy and, by most estimates, will have the largest economy within the next 20 years. It has the second-largest military in the world, and its military spending is increasing, although less rapidly than before. It is resource-poor and spends extensive political and financial capital on securing raw materials for its economy. It has land borders with more countries than any other country in the world—14 sovereign states and 2 special territories.

The country is governed by a Chinese Communist Party that is at once both paranoid about threats to China’s stability and the party’s legitimacy, and intent on maintaining one-party, top-down state control. Although ruled by a communist party, its economy is a highly dynamic and unique mixture of market capitalism and state paternalism, inspired by Deng Xiaoping’s vision for modern China and by lessons Chinese communists took from the collapse of the Soviet Union. In sum, China is an authoritarian colossus in a fragile transition, whose trajectory will have a major impact on every other country in the world, including the United States. It is clearly in the interest of all countries to try to shape China’s interests and future to converge with our own. And that will require a renewal of strategic, patient and firm coalition diplomacy to maximize the chances for success.

Some will say that our attempt to accomplish this over the past four decades failed, that the deadline by which China was to have transformed has been crossed, and that it didn’t happen. Others claim that China’s interests are increasingly diverging from those of the United States. Some claim that our efforts to engage China were naive, as if turning China into a democracy were the only goal of Nixon’s opening or of World Trade Organization accession. It is time now to abandon such efforts, they say, to “face reality and to get tough.”

Even if China does not become an electoral democracy, the power of American influence in the world will surely change China, just as China’s growing influence will change America.

In this telling—we’ll call it the “clash of titans” (not the “clash of civilizations”)—Xi Jinping’s “China Dream” will inevitably be raised as evidence of China’s “Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower.” The Chinese state, as this narrative has it, is seeking a global strategic military presence under cover of its Belt and Road Initiative and global and military technological superiority through its Made in China 2025 program (which encourages intellectual property theft); and its “community of common destiny for humankind” is a trope for a Sino-centric order in East Asia and beyond. Those who spin this narrative cite as evidence their reading of Chinese strategic and military documents, isolated cases such as the Sri Lankan port of Hambantota, and quotes from various Chinese officials and scholars.

The “China Dream”

But the “China Dream” is not defined in terms of the United States. Its mission is not, as Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev famously declared of his country, to “bury us.” Most countries, including China, do not formulate their national strategies—or think about their futures—through the prism of other countries. China has its own long and proud history and has conducted its own affairs for thousands of years. Chinese officials will tell you that the main focus of national energy is to be a well-off socialist society by 2049, the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Like their counterparts in other governments, they couch their goals in domestic and patriotic terms. The “China Dream” is to be rich, powerful, modern and admired. In other words, the China Dream is to be more like the United States.

This will be well understood by State Department employees around the world who are used to seeing American “soft power” at work in the field. The leadership, attitude and example of the United States as an open, free and tolerant society has powerful attractive force in the world. Even when governments in places like Iraq, Iran, Cuba and the Soviet Union opposed the U.S. government, their people were attracted by our principles. Even as a unipolar superpower that lurched, at times, into misadventure, the United States, as a benevolent hegemon, got the benefit of the doubt and the world’s support.

At a recent event in China, a high-ranking State Security Ministry official and a People’s Liberation Army general separately sought advice from American counterparts on getting their children (their only child in both cases) into universities in the United States. These children are not studying in technical fields. One wanted to study communications and media, the other international relations. These parents, who are not rich, are prepared to spend a huge proportion of their savings and income on sending their children to the United States to study. President Xi Jinping’s daughter studied and worked in the United States until he was elevated to general secretary of the Chinese Community Party. As any parent who has sacrificed for their children’s education knows, that says more about China’s attitude toward America than any strategy document or communist party pronouncement.

When you go to China and talk to young people, they’ll tell you that they don’t like the way the U.S. government talks about their country, but they all want to go to school in America, work for a U.S. company or travel to the United States. This is what success looks like. America is still “a shining city upon a hill” for most Chinese. They understand that China’s ability to reach its dream is inextricably bound up with continued connections to the outside world, including the United States. Of course, there are exceptions: Chinese nationalists who preach autarky, PLA officers who advocate militarism, Chinese CEOs who want protectionism. Some are powerful, as vested interests tend to become in maturing systems and economies, but they are a vocal minority.

Susan Thornton (center) at her farewell party with colleagues from the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs in July 2018.

Courtesy of Susan Thornton

U.S. Strategy Needed

The summer palace in Beijing.

Courtesy of Susan Thornton

It is impossible to say at this point what China’s future will be. It is still an open question. Those who would claim that China’s future course is set and unchanging are mistaken. If, due to our own ideological blinders and shortsighted political narratives, we abandon the effort and miss the opportunity to help shape China toward a better future, our children will rightly blame us. Even if China does not become an electoral democracy, the power of American influence in the world will surely change China, just as China’s growing influence will change America. It is delusional to think otherwise. The question is whether U.S. diplomacy will have some input in its design, or not.

We could, of course, continue to shun diplomacy and stoke the escalatory cycle of strategic adversity. This seems to be the direction for the foreseeable future. Those promoting this approach say that Beijing only responds to force, that tension is a necessary feature of the relationship and that Chinese and U.S. interests are implacably opposed. But even if claims about a secret Chinese plot to bury the United States were accurate, it is difficult to see how an endless string of U.S. provocations without a strategy and absent coordination with others will achieve anything other than heightened suspicions, further recriminations and, likely, a premature crisis. This will do nothing to further U.S. interests, to say nothing of the interests of our allies around the world, and it will harm U.S. credibility and leadership.

Allies and partners of the United States, many of whom rely on China’s economy as an engine of growth at home, are loath to see a rupture in Sino-American relations. They do not want to have to choose between the two biggest powers as they did during the Cold War. Some in the international community have even begun to voice fears that the United States, traditionally relied on to be the global guardian of peace and stability, has become ground zero for sowing disorder, instability and distraction. Not only is this not a productive strategy (or even a strategy—what is it meant to accomplish?), but it is playing into Chinese hands, undermining global confidence in U.S. leadership and squandering opportunities to reshape the international system in ways conducive to U.S. interests and power.

Diplomacy has fundamentally changed China over the past 40 years, and has been a major contributor to the peace and prosperity that East Asia has enjoyed over that same period.

The other possibility is to pursue a mix of engagement aimed at shaping and cooperation, while pursuing a policy of balancing and deterrence that has worked well for 40 years and shows few signs of being seriously challenged by China in the near term.

First, we need to put the lie to the notion that China doesn’t change, that it won’t respond to diplomacy, that talking to China is a waste of time, that it disregards agreements and wants to overturn the international system. Diplomacy has fundamentally changed China over the past 40 years, and has been a major contributor to the peace and prosperity that East Asia has enjoyed over that same period.

Although it has land borders with 14 countries and 2 special territories, a few of which remain disputed, China has not been involved in any major conflict since the normalization of diplomatic relations with the United States in 1979. This would certainly not have been predicted at the time, based on past behavior. Indeed, deterring Chinese military aggression toward what it views as a “renegade territory,” Taiwan, has been a chief preoccupation of U.S. diplomacy with Beijing since Nixon’s opening. So far, it has been successful.

Co-Evolution in the International System

China does not want to overturn the current U.S.-led international system. Chinese leaders understand that it is China’s opening and joining the international community that has brought about its spectacular modernization and the prospect of achieving the “China Dream.” The Chinese narrative on this is as follows: When Deng Xiaoping launched China’s opening and reform and the PRC gained China’s United Nations seat from Taiwan, China began a frenzy of joining international instruments and institutions. China had not been in on the rulemaking in the international system; but, starting in the 1970s, it joined every international convention and began to remold Chinese society accordingly. The Chinese government introduced a legal system, a market economy and national institutions that could contribute to the United Nations, other international organizations and to international decision-making.

The United States says China doesn’t follow the rules; but from China’s perspective, it has changed tremendously to incorporate international structures for the sake of international participation. We have seen great progress through decades of diplomacy on issues from nonproliferation to product safety, from contributing to solving regional conflicts to combating climate change. China has recently moved to a much more active and participatory profile on the international stage, something that the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations had held out as desirable in the “responsible stakeholder” concept to counter perceptions of China as a “free rider” on the international system.

China is now making several efforts to contribute more to international public goods through, for example, increased contributions to U.N. peacekeeping operations, efforts to combat pandemic disease in Africa and leadership in international organizations. It is providing infrastructure financing to the developing world through its creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Belt and Road Initiative, both of which have been maligned by the United States but have been attractive to many countries. In short, China understands that it has benefited tremendously from its participation in the international system, and that the continuation of the system is crucial to China’s continued growth and development. It is prepared to contribute to the strengthening of the system.

This does not mean that China rejects the need for reforms and adjustments to the international system; there are, indeed, aspects of the system that it does not like. But China is very invested, first and foremost, in the continuation of the international trading system; it does not want to see the dissolution of the World Trade Organization or the development of rival trading blocs. Because of its reliance on global trade for continued growth and development, China is willing to discuss needed changes in the interest of strengthening the WTO. China has also talked frequently about the need for “democratization” of international affairs, but it is not clear what implications this would have for specific reforms.

The only realistic path forward is for the United States and China to co-evolve, through cooperation and competition, into an adjusted and sustainable order.

As for the dislikes, most obviously China has rejected U.N. oversight of its human rights performance, an area of increasing concern with the incarceration of a significant proportion of its indigenous Muslim population on grounds of “terrorism prevention” and increasing suppression of views deemed critical of the leadership. This backsliding and frenzied increases in party control in recent years are causing grave concern about China’s future governance trajectory. China’s continued participation in U.N. human rights bodies, however, reflects its sensitivity about international opinion and its desire to be seen as a responsible player.

The international community must continue to put pressure on China to improve in these areas, to call out bad behavior, and to demand that China subject itself to criticism and improvement, in accordance with international expectations. While this may not produce immediate solutions, it has had and will have beneficial effects over time. Chinese bridle at what they see as continual interference in their sovereign internal affairs, but they are increasingly aware that this is the price of being in the international system. We should encourage the PRC to see these restraints on its internal behavior as positive for its own development, and the United States should set an example in this regard.

Given China’s rising role, continued U.S. leadership of the international system and the need to make adjustments to strengthen that system in the face of global and technological shifts, the only realistic path forward is for the United States and China to co-evolve, through cooperation and competition, into an adjusted and sustainable order. This is the path we have been on for the last 40 years without naming it. The United States, in many cases via the international system, has changed China. But China, through its modernization, has also changed the United States and every other country.

China’s active participation in international structures is now crucial to the development of the rest of the world. Its contributions will be key to making progress on the greatest challenges we face, which will continue to be transnational in nature. U.S.- China co-evolution in a globalized international system is the only realistic and productive path forward.

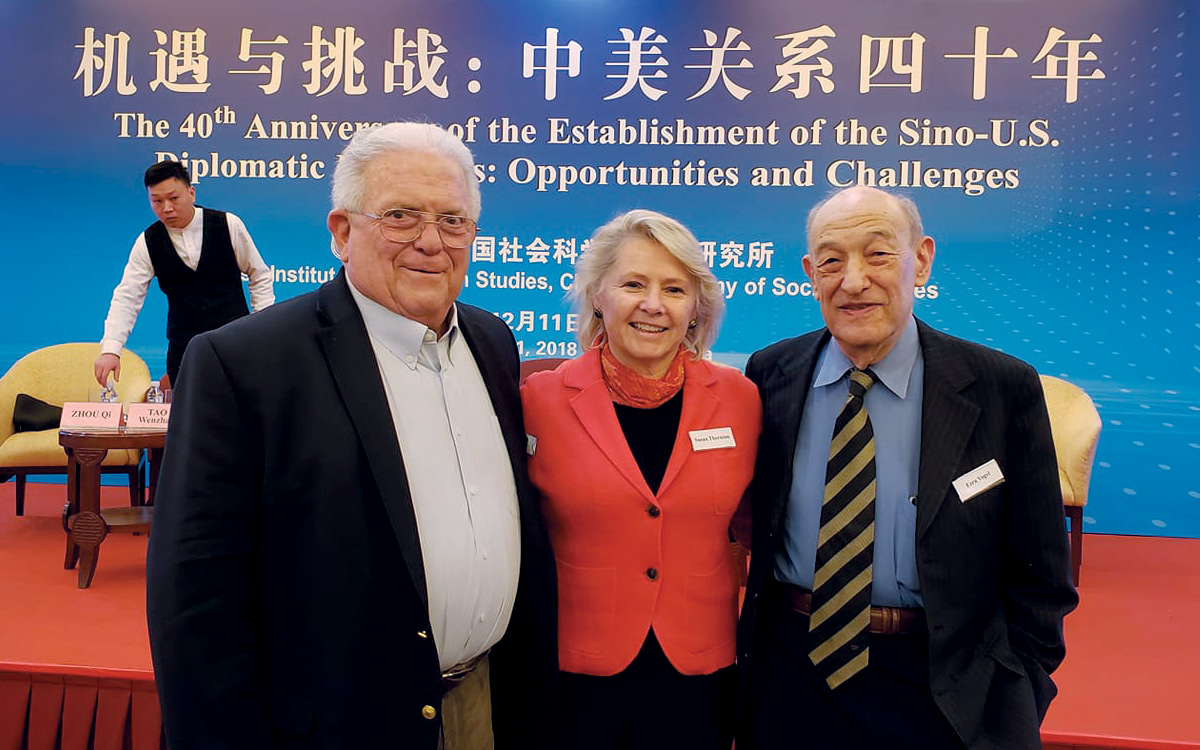

A bike-share stand in Beijing.

Courtesy of Susan Thornton

Doubling Down on Our Strengths

I recently had the chance to meet with a former Chinese leader who had spent a lot of time working with Americans on U.S.-China relations. He was sober about the turn things have taken in the relationship after 40 years of obvious sweeping benefits to both societies and the world. He reflected the perplexity of many Chinese I’ve spoken to recently when he said, “I don’t understand why you Americans are so afraid of China.”

He continued: “The United States has an ideal geographic location, friendly neighbors, rich resources, a young and talented population, the largest and most productive economy in the world, the most well-endowed military on the planet that outstrips the next eight combined, more than 50 allies and more than 100 military bases all around the world. You should be confident. America is not in decline—it is in constant renewal. Actually, if you think about it, America and China are the two most similar countries.”

“But as a friend of America,” he continued, “I must tell you that in international relations, pressure, sanctions and arrogance are corrosive and counterproductive. China is learning this lesson now and is trying to reach out to countries more positively.” He pointed to China’s outreach through the Belt and Road Initiative projects as an example. “China is not trying to replace the United States on the global stage,” he said. “We need U.S. global leadership, but we need it to be more humble.”

The skeptics will say that this is a trick. They will point to China’s military buildup, its development of advanced weapons, quotes by hardliners on social media and elsewhere as evidence of the “Secret Strategy.” And those Chinese prone to see threats also believe that the United States has its own “Secret (or maybe Not-So-Secret) Strategy” for containing China, blocking its modernization, infiltrating its military defenses and overturning the regime and the Chinese system. They have ample evidence they can point to in bolstering their case. But most Americans and most Chinese do not see each other as a threat and do understand that globalization will not go backward. It will continue to bring our two countries into more frequent contact, posing opportunities, challenges and dangers.

As the Chinese official cited above indicated, the United States remains the best-equipped nation to absorb and adapt to these wrenching changes, which will pose major challenges to all countries. But we must stop with the political distractions, put faith in our elected leaders and focus on real challenges. We must band together with partners, double down on coaxing China into the global community and strengthen international structures against looming pressures before it is too late. The stakes are high and the responsibility for getting it right is great.

Bring on the diplomats!