Earning American Credentials Abroad

Some Foreign Service kids want to stay overseas for college. What to do when a study abroad semester isn’t immersive enough?

BY LAUREN STEED

iStockPhoto / Olegsnow

You’ve grown up abroad, changing schools every few years, and you like that. Maybe you feel ready to take on the world. Your idea of adulting isn’t just learning how to live without your parents scheduling your days; it’s learning to navigate new languages and grocery stores without the security of an American school or diplomatic visa.

Or maybe you’re not interested in spending four years to earn a degree you could in three or spending $200,000 for a degree in the U.S. that could be nearly free overseas. Maybe you’d just rather be one flight away from the post where your family will be stationed.

Whatever your motivation, you’re considering applying to universities outside the United States. But you’re also worried about taking this road less traveled. And you worry that your international degree might not translate to a career in the United States.

There are several ways to enjoy an American university experience abroad while earning U.S.-recognized credentials that don’t require credit translations and credential evaluations.

The most common option is to study abroad for one year or one semester as part of a U.S. degree program. You can go in your third year, as is most popular, or start abroad and move to the main campus after your first or second term.

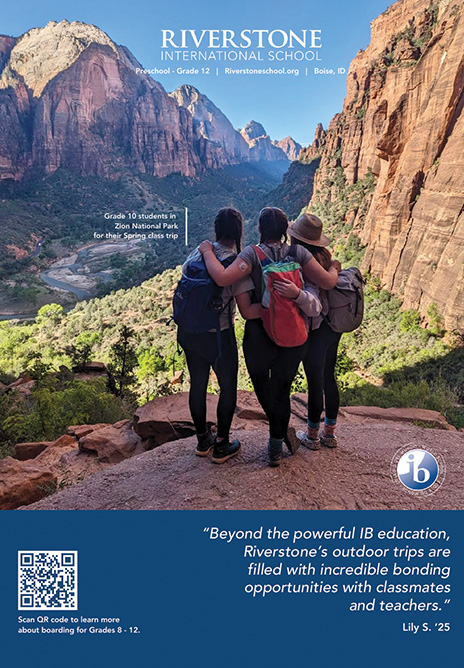

Or you can opt for a summer abroad, a January term, or even a class trip—travel with the archaeology class for a one-week excursion to a dig site in the Mayan jungle, for example.

You might spend a year aboard a ship, visiting many different ports; undertake a guided internship in an international corporation; or visit a branch site of your own school.

This classic way of experiencing a new culture is easy to plan and offers a soft landing for students who’ve never been abroad. But it’s not cheap: You will still pay American tuition rates. And some Foreign Service kids are ready to go beyond the traditional study abroad format.

In deciding what’s right for you, think more about what you want to get out of your college experience and consider the following.

1. “I want to explore several subjects before I choose a major.”

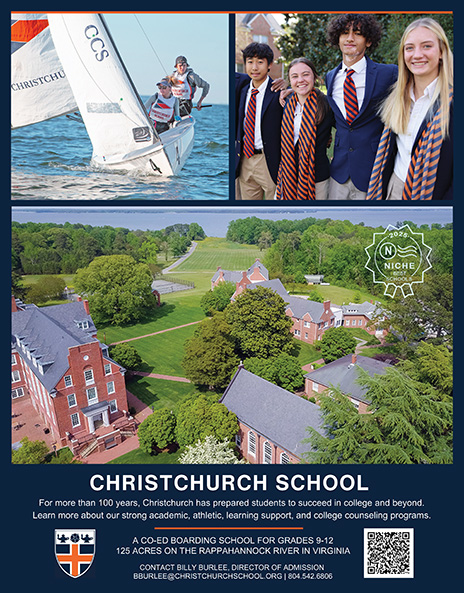

This student might want to study at an American-style university abroad. Schools like the American University of Paris (AUP) or John Cabot University in Rome are private universities purposefully created to provide postsecondary American education options outside the United States. They predominantly follow a liberal arts model, with the freedom to choose a major after enrollment, and require courses outside your field of study to ensure breadth and depth.

The most common majors are international studies and international business, but you’ll find majors in psychology, media, arts, communications, finance, tourism, and more. These schools will have the familiar blend of the international and the American that FS students understand from their international school years.

Some of these universities are quite small, with transient populations. Domestic U.S. students may spend a term at AUP to feel what it’s like to live in Paris before returning to their home school. The Irish American University (also known as the American College of Dublin) is one of the few universities in this category to offer a bachelor’s degree in performing arts—but it has an enrollment of fewer than 200 students, many of whom study there for one term only.

Some Foreign Service kids are ready to go beyond the traditional study abroad format.

In general, the tuition at American-style universities abroad is higher than the average tuition in Europe, but some charge significantly less than U.S. tuition rates. At the Anglo-American University in Prague, for example, international student tuition is approximately $6,000 per year.

There are also exploratory years built into degrees in Scotland and at the residential “University Colleges” at certain universities in the Netherlands. Students here start their studies primarily in one broad field, such as global and political studies or psychology, narrowing in on a more particular major, such as East Asian studies, in their second year.

The small size of some of these programs will, as at small liberal arts colleges in the U.S., give students a closer connection to their professors, helping them get the letters of recommendation they’ll need for graduate school or medical school applications while offering the same significant opportunities for leadership that smaller international high schools provide.

2. “I want to be abroad longer than a semester or year, but I might not want to spend all my university education abroad.”

U.S. Schools’ Overseas Campuses. Students who apply to Northeastern University near Boston are sometimes surprised by an admissions offer that requires them to spend their first semester outside Massachusetts at one of Northeastern’s campuses in London or California, or as a visiting student at one of the American liberal arts colleges abroad mentioned above.

This alternative matriculation pathway, known as the “N.U. In” program, helps Northeastern manage their housing availability and keeps their on-campus population stable.

N.U. In, Bard’s Begin in Berlin, New York University’s (NYU) Freshman Year Abroad, and similar programs at other campuses are also offered as an opt-in. Students who choose to spend their first year abroad will benefit from a small cohort of students who are on the same plan and complete the same general studies courses in a smaller setting.

This is not the only way schools use their facilities abroad, however. NYU’s Abu Dhabi campus was initially designed to provide an American education to students from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. Students can complete an entire degree at the Abu Dhabi campus in any of 26 majors, with more than 500 courses offered each year.

They can “study abroad” in the United States or at any of NYU’s 15 global campuses. Degrees from NYU Abu Dhabi are equivalent to degrees from NYU’s main campus, and the program is even more selective than the New York campus, with only 4 percent of applicants admitted.

This selectivity is unusual, however. Admission to the branch campus is often less selective than to the main campus. At the Rochester Institute of Technology’s (RIT) campus in Dubai, hopeful engineering majors need only a minimum combined international baccalaureate (IB) of 24 with at least two lab sciences and completion of high school precalculus.

At RIT’s main campus, engineering applicants must have taken physics and chemistry, and a year of calculus is strongly preferred. Average grades in all courses should be in the upper 90 percent.

RIT-Dubai students can study at the main campus for a year or transfer there after completing their first year. This could be an ideal pathway for an internationally schooled student who is interested in a career-focused science degree.

The tuition at American-style universities abroad is higher than the average tuition in Europe, but some charge significantly less than U.S. tuition rates.

The “Joint Degree” Option. Another option is to look for a “joint degree,” for which students spend time on two or more campuses and earn one, two, or even three degrees in the time it usually takes to complete one.

Students interested in economics or international business will find a significant number of joint degree options, most of which include coursework on two or three different continents, but you will be able to find a joint degree option for almost any field of study.

You can earn two bachelor’s degrees by studying tourism in Dublin, London, and the U.S. as part of Schiller University’s joint degree partnerships with the Dublin Business School and the University of Roehampton; neuroscience at Trinity Dublin and Columbia in New York; law at St. John’s in New York and Goldsmith’s in London; fashion design or marine engineering at the State University of New York (SUNY) and one of seven universities in Türkiye.

And for those who are hoping to get both an undergraduate and a graduate degree in five years, programs in computer science, engineering, and communications are offered via partnerships tied to Carnegie Mellon, Columbia, and Emerson College.

Traveling Universities. A “traveling university” is much more unusual. These programs require that students transfer between campuses regularly. At Minerva University, for example, students spend their first year in San Francisco and then rotate each year to campuses in global capital cities.

Long Island University’s Global degree (LIU Global) offers the reverse, three years at various locations abroad, capped with a final year at LIU’s Brooklyn campus.

Both programs are designed to take advantage of the changing locations, connecting students with local internships, on-site research, and immersive language lessons.

At either of these—as at Hult International, Franklin University Switzerland, or Schiller, three other internationally mobile universities—the final degree is accredited in the U.S.

3. “I want deep immersion in another culture, but also want a degree that’s accepted in the U.S.”

Earning a degree easily recognized in the United States does not require enrollment at an American-style university. At the time of writing, 66 universities outside the U.S. offer degrees in English (or in host-country languages) that are accredited by one of the six Council for Higher Education Accreditation–recognized accrediting bodies in the U.S.

This accreditation can happen at the institutional level, much in the way your international school is accredited in the U.S.; a university may also offer degrees that are accredited for specific circumstances.

Another option is to look for a “joint degree,” for which students spend time on two or more campuses and earn one, two, or even three degrees in the time it usually takes to complete one.

Courses from international institutions fully accredited in the U.S. should transfer as easily as courses within the U.S. transfer to other institutions. When applying for graduate programs, these degrees should be considered as equivalent to degrees from similarly accredited U.S. institutions.

The University of the South Pacific, for example, with a main campus in Suva, Fiji, is accredited by WASC, the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, the same body that accredits schools in California, Hawaii, and many other western states.

Why just go to the South Pacific for a short-term visit as part of your marine science degree when you could spend all four years there, with regular internships and research opportunities on site at some of the most fabulous reefs on the planet—and with an average total cost of attendance under $20,000 per year?

Other options fall into a gray area of accreditation: These are international universities that have partnered with their U.S. counterparts to offer brick-and-mortar domestic U.S. degrees. For example, Arizona State University (ASU) and Cortana Education have partnered to provide ASU degrees at 22 university campuses around the world.

At Sunway University in Malaysia, for example, you can complete a four-year ASU degree in digital media, computer science, psychology, and several other fields, with accreditation provided via the affiliation and oversight of the program by ASU’s faculty. These programs provide students the opportunity to live at post, study in person, and still graduate with a degree from a stateside American university.

When the accreditation is at the programmatic (i.e., major/course/degree) level, students will benefit not from transferability to U.S. degree programs but from their eligibility for professional certifications and licenses.

ABET, the accrediting organization for engineering fields, accredits individual degree programs. Successful completion of the degree is a minimum requirement for eligibility to sit for professional and state-level certification or licensing exams in a particular field of engineering.

Similarly, degrees at some universities outside the U.S. may have U.S.-based programmatic accreditation for educator preparation (CAEP), veterinary medicine (AVMA-COE), business (ACBSP, AACSB, or IACBE), nursing (ACEN), and so on.

National applications in many countries are straightforward, and the costs are clearly stated.

Graduates of those programs should be eligible to take state or national licensure exams without needing additional coursework; but, as you’ve likely heard before, it depends on the institution and state. Do your due diligence on eligibility before investing in such a program.

Of course, enrolling at a host nation university comes with some cultural differences. At the University of the South Pacific, for instance, residential students are expected to bring their own mop, bucket, and cooking appliances, but not their own bed linens.

In many European countries, student accommodations are provided by third parties, so your neighbors might attend different universities. And you can choose to live hostel-style with a basic bed and locker in a shared bunk room or have your own private bedroom.

Universities with a high number of international students will often support incoming international students in the hunt for accommodation in the first year, but finding and paying for housing is often one of the most complex parts of attending a local university outside the U.S., particularly if you do not already have access to a local bank account or student ID.

It is not unheard of to stay in a hostel or hotel for a few weeks while searching for your long-term student housing. In the Netherlands, where students far outnumber the available beds, the government has begun to restrict international student admissions and visas if the student cannot demonstrate that they will have housing upon enrollment.

4. “I want a simple, easy-to-understand admissions process and cost transparency.”

Application for postsecondary study in the U.S. has become astonishingly difficult. The Common Application and its various supplements—e.g., additional essays, self-reported (SRAR) transcripts, InitialView interviews, and Glimpse videos—as well as the seemingly incomprehensible financial aid process have made applying onerous. But if you’ve already filled out the Common App, keep in mind that it is accepted at some foreign universities.

National applications in many countries are straightforward, and the costs are clearly stated. Consider trying something like Concourse or Cialfo’s Direct Apply, which allow you to apply to nearly every university in the world simultaneously. Concourse acts as a promoter, showing the student’s profile to schools interested in attracting students like them and offering admissions and scholarships directly, with no requirements beyond submitting final grades or AP/IB scores after graduation.

International students applying to host nation universities may find it hard to understand how to apply, or what deadlines and requirements they need to meet. Websites at host nation universities are often much less informative than those of U.S. schools. Schools may have individual admissions offices for each degree program, or they may list only their domestic requirements.

Enrolling at a host nation university comes with some cultural differences.

In some cases, students will need to call individual offices at the school to discuss support options or confirm arrangements. The expectation in Australia, for example, is that international applicants will work with a recruitment and visa agent to navigate admissions, arrival, and enrollment, but this is not a requirement for U.S. citizens.

U.S. federal loans, 529 plans, and GI Bill funds can all be used abroad, but not universally. Different schools, courses of study, student types, and funding sources will affect whether these can be used. Search the current list of federal loan–eligible institutions abroad to confirm whether this is a viable payment option.

Life as a student abroad is different from life as a dependent of someone under chief-of-mission authority. Students need to secure local bank accounts, access local health systems, and navigate the oddities of cell phone plans and online payment-sharing apps when multiple currencies and nationalities are involved.

Universities with a high number of international students are more likely to offer significant support for these startup hurdles. They may even offer orientation programs or special international students’ support offices. Once enrolled, students must be fully prepared to take care of their paperwork, payments, health care, and financial arrangements.

Finally, the most significant difference between an American-style university education and one outside the U.S. is that persistence—the likelihood that a student will return for the second year—at most global universities is lower than the persistence rate in the U.S.

Lower tuition, larger and more impersonal classes, student realizations that their chosen degree isn’t a great fit, and testing and performance cut-offs mean that each year the cohort of peers shrinks significantly. While most Foreign Service kids are used to saying goodbye, they might struggle with the “survival of the fittest” mentality that marks the student experience at some institutions.

Before choosing a university education abroad, learn more about the different possibilities for obtaining a degree that will provide the most likelihood of transferability and recognition. You’ll find American-recognized degrees at universities around the world, at all levels of cost and global prestige, and in almost every possible field.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Foreign Service Student Guide to Creating a College List” by Hannah M. Morris and Lauren M. Steed, The Foreign Service Journal, June 2018

- “Getting a Degree Overseas: An Option Worth Considering?” by Rebecca Grappo, The Foreign Service Journal, June 2022

- “Dr. Lauren Steed & Nomad Educational Services,” Available Worldwide Podcast, April 2024