Employee Plus One: Marriage and the War for Talent

Speaking Out

BY MICHAEL GUEST

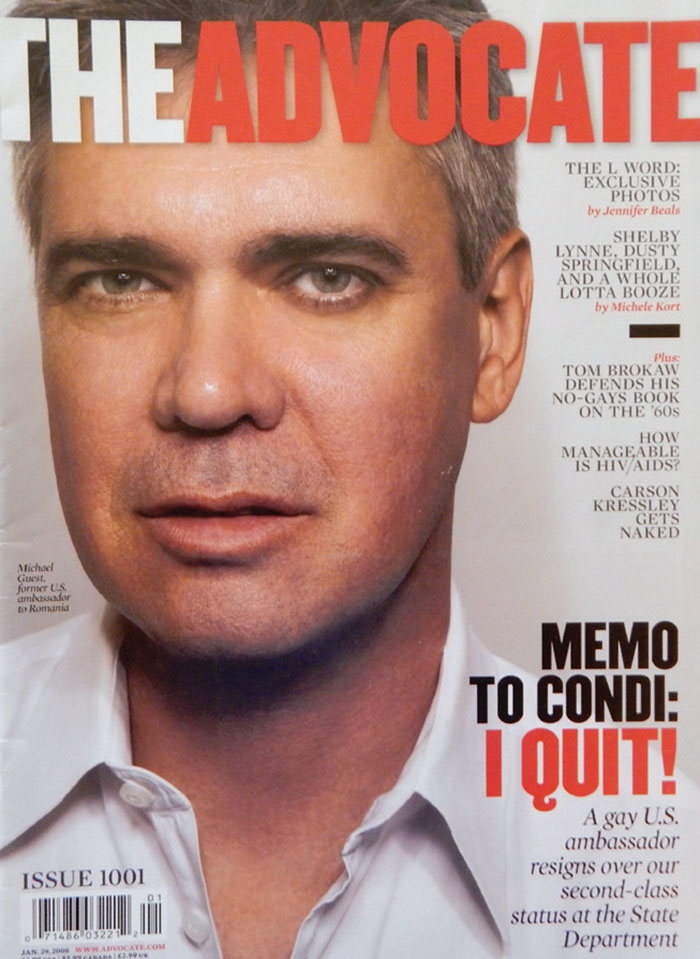

Michael Guest on the Jan. 29, 2008, cover of the nation’s leading LGBT news magazine, The Advocate.

In 2001, I was sworn in as our country’s first Senate-confirmed, openly gay ambassador. Six years later, I pulled the plug on my Foreign Service career, in protest of the State Department’s refusal to remedy policies that discriminated against gay and lesbian Foreign Service families stationed abroad.

Those twin milestones seem like ancient history now. Today partnered gay and lesbian employees are covered by the same transfer, housing, training and other support policies their straight married colleagues have long enjoyed. The policy changes pioneered at State have become a template for similar accommodations across the federal foreign affairs agency community.

In addition, six openly gay ambassadors, one a career officer, have been tapped by the Obama administration to serve our country. A new special envoy position has been created to strengthen how we integrate lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender issues into our broader human rights policy goals.

Yet these appointments are less remarkable than the paucity of organized public or congressional opposition to the notion that LGBT human rights matter, or that a gay person can represent our country abroad.

An Easy Write?

When the Journal sought my assessment of how matters have changed for State’s LGBT employees, I expected it would be a breeze to write. Our country is changing rapidly on these matters, after all, and Foreign Service policies have changed, as well.

But as we enter the Obama administration’s home stretch, department managers have proposed an effective end to the same-sex domestic partner program. Such a move would adversely affect LGBT employee families and careers, blemishing in turn both the administration’s and Secretary of State John Kerry’s distinguished record of support for LGBT-fair policies.

Ending partners’ equal access to benefits would also have negative repercussions for State’s Foreign Service mobility needs. It would drop State behind many corporate and multinational employers, too, and set back innovation in how the department retains its talent, gay or straight.

Let me explain.

The Negative LGBT Impact

On its face, the argument for ending the partner program is simple. Marriage equality now exists in 37 states, and a Supreme Court ruling expected soon, perhaps even by the time this article is published, may institutionalize that equality nationwide.

But that optimism ignores the situation in many of the countries to which LGBT talent and their families are assigned. Given that navigating foreign cultures is bread-and-butter to the department’s many missions, State should take greater note of that reality.

From my work with the Council for Global Equality (www.globalequality.org), I naturally see value in having openly LGBT personnel representing our country abroad, particularly in countries where fairness is little understood. Personally, I also support marriage equality and believe strongly in the public and community commitment that marriage represents. My own marriage is perhaps the best decision I ever made.

Still, gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender friends and colleagues at State and other foreign affairs agencies are keenly aware that overseas postings render decisions on whether to marry their partners complex. They are entitled to that same understanding by their employer.

Department managers have proposed an effective end to the same-sex domestic partner program.

My involvement with the Council attunes me daily to dangers in many places around the world that often attach to LGBT individuals. In some cases, the partners of lesbian and gay foreign affairs agency employees hail from countries where these threats are grave. For them, an act of marriage—entirely traceable in today’s Internet age—could carry negative consequences, especially for families back home.

And just as tabloids already have maliciously exposed the identity of gay people in many homophobic countries, surely they could do the same for our own personnel. In that respect, the public aspects of a marriage-for-benefits policy could complicate assignment of gay Foreign Service personnel to a range of gay-unfriendly places. It also would seem to counter the department’s own interest in assuring worldwide availability of talent.

No doubt State will pledge to implement any change in policy flexibly, to account for special needs. But once out of the bottle, the genie cannot be put back in. A recorded marriage may be fine in Paris. But in today’s world, might open-source knowledge of that marriage impede an onward assignment elsewhere?

Wider Understanding of Diversity

What I find far more troubling about the department’s trial balloon, however, is what it indicates about State’s blind spot in addressing the needs of unmarried employees and their families in the multidimensional workforce its “Strong State” agenda is presumably meant to support.

To be blunt, tying benefits to marriage, rather than to the employee, seems a surprising throwback to … you guessed it, the administration of President George W. Bush. State leaders during his presidency consistently turned back all requests to address LGBT family needs by citing the supposed limitations of the Defense of Marriage Act.

Citing that law, of course, was a red herring. Family support is as much a prima facie need for LGBT employees as it is for our straight colleagues, and including partners in the Foreign Affairs Manual’s already-expansive definition of “eligible family members” was an easy and obvious fix.

The “eligible family members” solution was one of the recommendations offered by President-elect Barack Obama’s State Department transition team, on which I served. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton’s early adoption of it led to one of the most striking innovations of the administration’s 2009 domestic partner program: tacit recognition that the department could base the provision of employee benefits on a broad definition of family, rather than on marital status.

Six years later, why would the Obama administration retreat to a retrogressive position—again pinning provision of Foreign Service benefits to marriage, rather than embracing, without qualification, all families that accompany our employees abroad?

Putting Families First

Instead of ending the partner program, logic would call for its expansion to include all unmarried couples, gay and straight alike.

Since leaving our Service, I’ve been privileged to work with, and learn from, talent-support professionals from some of America’s best corporations. Most understand that their job is as much about retaining talent as it is about offering a solid, entry-level job. Innovative policies to match what their companies’ best employees—single or otherwise—need and expect is a preoccupation, not an incidental concern.

Great companies pull out stops to make themselves employers of choice. They stay out of the marriage license business, opting instead for “employee plus one” insurance and other benefits policies. If the department isn’t willing to modernize its policies (or is just too cheap to do so), it may as well drop any pretense of being serious about winning the so-called “war for talent.”

A marriage-for-benefits policy could complicate assignment of gay Foreign Service personnel to a range of gay-unfriendly places.

An even-handed partner support policy—accessible by all, without respect to marriage—could be based on the relationship affidavit requirements contained in State’s current same-sex domestic partner program. It would reflect service equities across our institution and community. It would be fair, and would help State assure talent mobility to meet mission-based needs. It also would reflect the realities of today’s workforce expectations, in a highly competitive international job market.

Given the strains that overseas service inherently places on newly minted, not-yet-ready-to-marry couples, unmarried employees don’t need shotgun weddings. They need employment mechanisms to support their developing relationships, and to help lead toward stable marriages. Given the fact that unmarried LGBT employee families already can receive partnership benefits, surely legal issues can be resolved to extend those same benefits to all unmarried employees.

Watching Each Other’s Back

A decade ago, when I was fighting the department’s old, exclusionary policies, I became disillusioned at how little support I received from our Bureau of Human Resources. Indeed, the director general at the time told me flatly and definitively that nothing could be done.

Ultimately, that proved not to be the case.

When Senator Obama’s campaign called me in 2008 and pledged to fix these policies, I began a journey toward believing again in the political process. By the time I sat down with Secretary-designate Clinton, during the transition, to discuss the discriminatory impact of State’s practices, her leadership in seeking a policy reversal seemed certain. She and Cheryl Mills, her talented chief of staff, approached gender and LGBT equality from the standpoint of principle.

This time, I want to believe that the department’s senior-most career management leaders—those on the seventh floor, and in the front offices of key bureaus—will be our champions. I want them to present the case not only as to why continued LGBT accommodation is needed, for the well-being of gay and lesbian personnel who serve abroad, but how the service equities of our unmarried straight colleagues demand the same treatment for them. I want our career managers to fight for what’s right for the long-term future of our Service, and of the men and women who support American interests abroad.

I say this not to minimize the importance of political leadership. Sec. Kerry is a proven LGBT ally, and one who surely understands that supporting his people is critical to their, and ultimately his, success. I’d like his tenure to be remembered for ratcheting personnel policies forward to better meet the needs of our multifaceted workforce.

But wouldn’t it be heartwarming if those charged with advancing career Service needs were the ones to stand up and champion those changes? Wouldn’t it be reassuring to know that we in the career Service have each other’s back?

The question isn’t whether we career diplomats, past and present, can take a leadership role in transforming our personnel support from good to great.

I know we can. The question is whether we will.

Read More...

- Christian A. Herter Award—Michael Guest, Regarding LGBT Rights (The Foreign Service Journal, Sept. 2013)

- Council for Global Equality (CGE website)

- Gay Ambassador Resigns Over State Department’s Discrimination Against Gay And Lesbian Employees (Think Progress, Dec. 4, 2007)

- Speaking Out—Member of Household Policy: Failing Our Families (The Foreign Service Journal, March 2008)