From the FSJ Archive: Migration and Immigration Policy

The Stupendous Visa Task

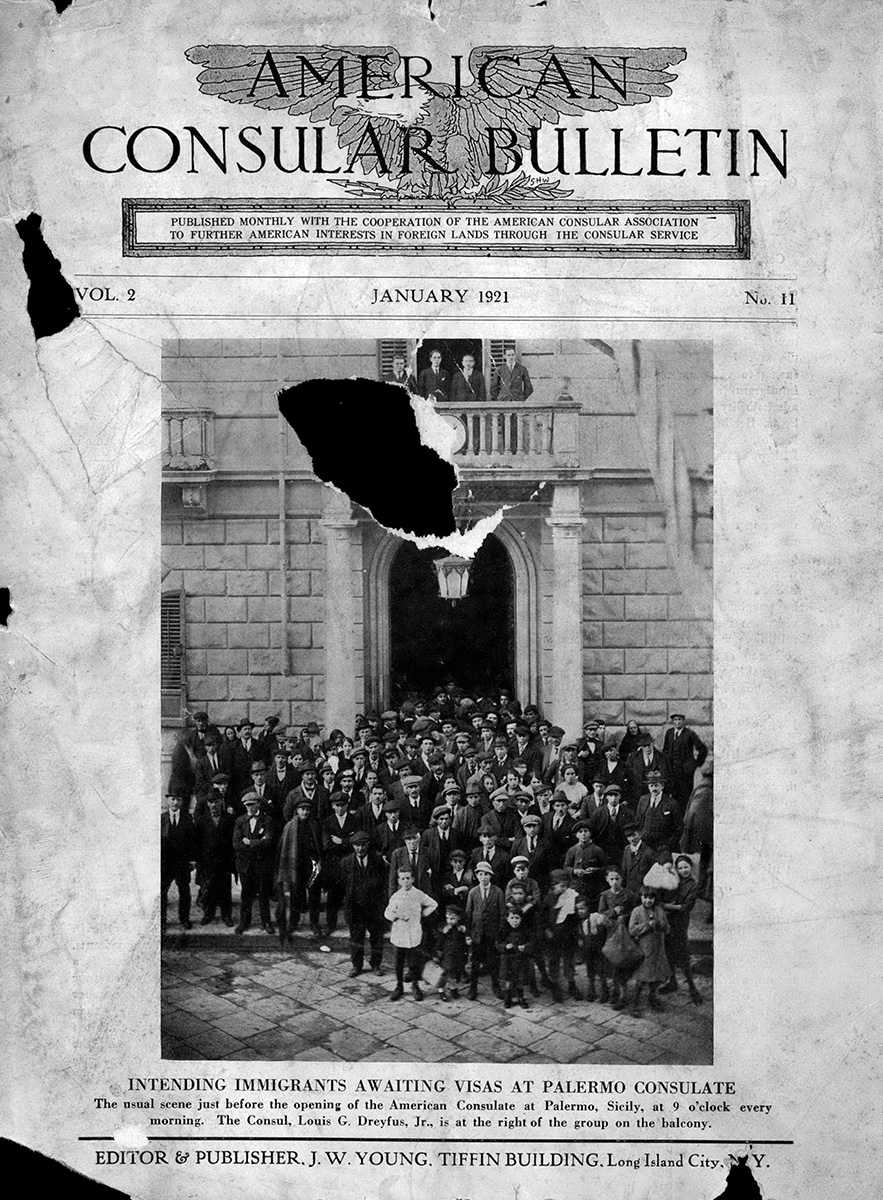

American Consular Bulletin, January 1921

Consul Harry A. McBride, back from an inspection trip to Europe, tells how consuls are regulating, by visas, the stream of immigration now setting toward the United States. …

Mr. McBride says that probably never in the history of Consular Service has such a tremendous task been placed upon the shoulders of our officers, as the work of the alien visa control. This work requires most of the time of the majority of our officers in Europe today.

“Up to the present,” McBride continues, “Naples has been the office handling the greatest number of visas, but Warsaw is now going ahead. … There is a wide balcony around [the building housing the visa office] and in the front portion four office rooms. The applicants, sometimes to the number of 2,000 in one day, line up on the balcony. They then pass through the offices. In the first office there are ten desks, where the applications are made out with the assistance of consulate clerks. …

“From very careful estimates prepared by each consular officers, it is found that 202,493 visas have been granted in Europe during the quarter ended Dec. 31, 1920; that 257,178 will be granted during the quarter ending March 31, 1921; and 297,484 during the quarter ending June 30, 1921, or the large total, for the present fiscal year, of 931,549 visas in Europe. To this must be added the following estimated figures: Africa 9,000; Asia 25,000; Mexico 100,000; West Indies 17,000; Australia 9,000; Canada 2,000; South America 12,000; Central America 8,000; a total of 182,000 in non-European countries, making a grand total of 1,113,549 visas for the present fiscal year. This means a revenue of some $11,000,000! The rate of increase per quarter is also a figure which should be punctuated with an exclamation point.

“In addition to the visaing [sic] of all foreign passports there is another branch of this work which requires considerable time and attention on the part of the consular officers. This is the visaing of crew lists. All vessels bound from foreign countries for ports of the United States and its insular possessions or the Canal Zone, must present a list of all alien members of the crew to the consulate abroad before sailing. These names must be checked and the list visaed [six] if found to contain no suspected aliens.

“The work of visa control would be about all that the Service could handle if it ran smoothly, but recently the path has been found to contain treacherous windings and dangerous pitfalls. The number of passport frauds, forged visas and the like, that have to be combatted, is considerable—especially in Eastern Europe.”

National Origins Quota System at Issue

Foreign Service Journal, December 1955

On June 27, 1952, a well-known bill became law when the Congress passes Public Law 414 over the veto of President Truman. The Act [known as the Immigration and Nationality Act and the McCarran-Walter Act], which became effective on Dec. 24, 1952, can now be evaluated more accurately than was possible three years ago.

The purpose of codifying and integrating all immigration and nationality laws within the framework of one statute was accomplished. The purpose of revoking obsolete laws was achieved. The purposes of removing racial bars to naturalization and immigration and of elimination of discrimination between sexes with respect to immigration have been fulfilled. With these major accomplishments listed on the credit side one may well ask what more can be expected from one piece of legislation. And it is on this point alone—expectation—that the answer depends.

Defenders of the law point to these accomplishments and improvements, and state that the favorable results obtained exceed their original expectations. They concede that minor amendments are desirable to eliminate injustice and discrimination in certain individual cases, but they insist that the national origins quota system established in 1924 be perpetuated as a necessary foundation for American immigration policy. Critics, however, claim that the expectations, as well as the hopes and prayers of millions of people all over the world, have been sadly crushed by the McCarran Act, principally because it had perpetuated this quota system, which they consider to be antiquated, unrealistic, and cruelly discriminatory against certain races, religions and countries.

—Fred M. Wren, FSO, from his “The McCarran-Walter Act”

Reform Depends on Compromise

Foreign Service Journal, October 1983

Whether Simpson/Mazzoli [the Simpson-Mazzoli Act, or Immigration Reform and Control Act] passes in this session—or any session—ultimately will depend on reaching a compromise among the various interest groups that have helped stymie it and their congressional supporters. These are the domestic groups that have played a leading role in the debate over immigration laws:

• Hispanics. The national leadership of organizations like the League of United Latin American Citizens opposes the fines for employers of undocumented aliens out of fear that they will lead to employment discrimination against all Hispanics. At the least, they would like to see the creation of a separate commission to hear complaints of discrimination based on alienage.

• Growers. As the segment of the U.S. economy most dependent on undocumented workers, agricultural growers have fought hard for concessions that would preserve their labor force. This year, Mazzoli accepted a three-year transitional program that would allow the Southwest farmers to phase out the use of undocumented labor. The bill also would expand an existing program that allows the importation of foreign workers under controlled conditions.

• Organized labor. Unions favor the employer fines as a means of opening up more jobs to U.S. citizens. But they are opposed to the bill’s proposed expansion of the Labor Department’s foreign worker program unless the interests of American workers are thoroughly protected. Lane Kirkland, president of the AFL-CIO, has said he cannot support a bill that does not have both a generous amnesty and the amendments to protect the U.S. labor market that were passed by the House Education and Labor Committee. Mazzoli has opposed such proposals in the past.

• Civil liberties groups. The American Civil Liberties Union is worried by the provision in both House and Senate bills calling for the administration to develop “a more secure identification system.” This concept is implicit in employer sanctions since companies will need to check reliable documentation before hiring new workers. The Senate bill now requires all Americans hired after its enactment to present two forms of identification. Civil libertarians fear this could lead to a national identification card, a goal denied by Simpson.

—Stephen P. Engelberg, Washington correspondent covering immigration issues for the Dallas Mornings News, from his “Consular Affairs and Domestic Politics”

A Surge of Job-Seekers Is Inevitable

Foreign Service Journal, December 1994

In 1972, after two years of studies and hearing, a presidentially appointed commission, headed by John D. Rockefeller III, delivered its report, “Population and the American Future.” The Rockefeller Commission recommended, among other things, that the government cap immigration at 400,000 people a year.

In terms of migration to the United States, what has happened since 1972?

• Annual levels of legal immigration to the United States have just about doubled, from 500,000 in 1972 to 1 million in 1994.

• Annual levels of illegal immigration have at least doubled to an estimated 300,000 permanent settlers, mostly from or through Mexico.

• Meanwhile in 1980, 1986 and 1990, three major bills on immigration were passed by Congress, all of which helped raise legal immigration levels. The 1986 bill automatically provided legal resident status to more than 3 million people who had entered the United States illegally before 1982.

The prospect of increasing pressures on U.S. borders is downright alarming, since the world’s population is growing by 100 million a year, with the economic gap ever widening between the richer, industrialized nations and the poorer, developing nations, where virtually all population increases are occurring. Meanwhile, the poorer countries face increasing levels of unemployment as work forces grow every year by 50 million, while the mechanization of agriculture and the automation of labor-intensive industries like textiles have eliminating many jobs. A surge of job-seekers to the United States is inevitable, whether through legal or illegal channels.

So what can be done? The United States’ first and most immediate task is to enforce existing immigration laws and regulations more effectively.

—Marshall Green, retired FSO and former ambassador, from his “Stop, All Ye Who Enter Here”

Immigration Run Amok

Foreign Service Journal, June 2001

We should stop conferring immigration benefits on aliens illegally residing in the United States. This means an end to amnesties, temporary protected status and adjustment of status. Unless those who enter the country illegally or who violate the terms of their visas are made to pay a penalty, the immigration law is nothing more than an easily bypassed obstacle for all but law-abiding people. In FY97 less than half of the immigrant admissions were new arrivals. The majority adjusted their status in the United States. The INS doesn’t say how many of those who adjusted status were in legal nonimmigrant status, but it is a small share.

—Jack Martin, an FSO from 1961 to 1989, from his “Immigration Run Amok: Why We Need Reform”

America’s Split Personality on Immigration Policy

Foreign Service Journal, June 2001

Our immigration policies are imperfect in part because we seek to balance our competing interests in maintaining both openness and control. But the United States makes at least two avoidable errors in its immigration system. First, we pursue the problem of illegal entry with excessive emphasis on a border defense strategy. A much more effective way to prevent illegal entries would be to prevent illegal aliens from working. Second, we fail to allocate the resources for prompt and careful adjudications of immigrants’ claims.

Border control can only do so much: When we fail to control who is allowed to work in this country, it becomes difficult for the Department of State and the INS to regulate the massive flows of immigrants who enter the country, no matter how many resources are put at their disposal.

—Bruce Morrison, former member of the House of Representatives (1983-1991) and chair of the House Subcommittee on Immigration (1989-1991)