Fulbright Program at 70: The Foreign Service Connection

Members of the Foreign Service, some of them Fulbright alumni, play a crucial role in the continuing success of this singular U.S. exchange program.

BY JEROME SHERMAN AND JAMES LAWRENCE

Al Azhar University in Egypt, established in 969 A.D.,is the oldest, continuously operating institution of higher education in the Muslim world. FSO Martin Quinn (see below) took this photo of the Al Azhar gate in 1979 when he taught American civilization there on a Fulbright lectureship.

Courtesy of Martin Quinn

Martin Quinn, top left, with his Al Azhar students. The students are holding Quinn’s daughters, Esther and Suzy.

Courtesy of Martin Quinn

The Fulbright Program, celebrating its 70th anniversary this year, is recognized as the flagship U.S. government educational exchange program and continues to attract record numbers of applicants.

Approximately 8,000 individuals from the United States and more than 160 other countries participate in the program annually, returning home to join a global alumni network of more than 370,000. Among their ranks are 54 Nobel Prize recipients, 82 Pulitzer Prize winners and 33 current or former heads of state or government. Many thousands of others have had a major impact on their local institutions and communities and in expanding international connections.

Over the years, the Fulbright Program has adapted and diversified its models, areas of emphasis and applicant recruitment to reflect a changing world and stakeholder interests. But at the same time, it has maintained its fundamental principles, such as a transparent, merit-based selection process. Once best known for its awards to U.S. artistic luminaries, the program now also makes about 30 percent of its awards in scientific fields.

Today China, India, Mexico and Pakistan boast some of the largest Fulbright programs in the world, with Pakistan having the largest.

Sponsored by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, and overseen by an independent, presidentially appointed board, the Fulbright Program is notable for its binational partnership structure—including 49 Fulbright Commissions around the world—as well as the high level of cost-sharing it attracts from foreign governments, academic institutions and the private sector.

U.S. Foreign Service officers, including those who are Fulbright alumni, continue to play a crucial role in the program. FSOs serve as administrators of the program abroad—either within embassies or on binational Fulbright Commission boards in partnership with foreign governments. These boards work with locally employed embassy staff, as well as with State Department colleagues and nongovernmental partner organization employees in the United States.

Adaptation and Diversification

The State Department has developed new and enhanced program models to respond to bilateral priorities. For instance, the Fulbright Specialist Program sends U.S. experts on migration issues to work with European countries grappling with the influx of migrants from Syria and elsewhere. In Greece a Fulbright specialist assisted the Athens municipal government in setting up a process to ensure that refugees were effectively matched to available resources.

Fulbright’s Regional Network for Applied Research Program (known as NEXUS), which recently concluded its third two-year cycle, brings together a multinational group of scholars, professionals and applied researchers from across the Western Hemisphere, including the United States, to engage in collaborative research on climate change and adaptation strategies.

Established in 2015, the Fulbright Arctic Initiative supports a cohort of 17 scholars and researchers from all eight Arctic Council member nations to study the changing Arctic. The initiative will have its final plenary meeting in Washington this October, where scholars will present the outcomes of their collaborative research and policy recommendations for building a resilient and sustainable future for the Arctic region.

Fulbright alumni invariably describe the program as “transformative,” and many have gone on to distinguished careers in government, science, the arts, business, philanthropy and education around the world.

Fulbright also responds to the worldwide demand for English language education. The popular Fulbright English Teaching Assistant Program for recent American college graduates has grown from about 100 participants annually 15 years ago, to more than 1,000 a year today. Once focused primarily on a handful of developed countries in Europe and Asia, the Fulbright ETA Program now operates in 70 countries across the globe, with extensive funding from partner governments.

Promoting and achieving diversity in all components of the Fulbright Program, for both American and international participants, are high priorities. Because it does not require a specific research proposal or in-country affiliation, the Fulbright ETA Program helps the State Department broaden and diversify the pool of applicants for Fulbright U.S. Student Program awards. Moreover, since the Fulbright Foreign Student Program continues to face challenges in some countries in recruiting participants beyond major cities and traditionally elite universities, it has responded by offering long-term English language training in the United States. This is designed for selected international participants who have the talent and motivation to succeed, but need to gain fluency in English before beginning their U.S. graduate studies.

Over the past decade, the State Department has also pursued new, innovative partnerships with the private sector. The Fulbright-National Geographic Digital Storytelling Fellowship sends five fellows abroad for an academic year to research and create stories on topics that are relevant to both the United States and the host countries. For example, Fulbright alumnus Ryan Bell recently returned from travels through Russia and Kazakhstan, where he documented how American cowboys are helping to rebuild the Russian and Kazakh cattle and beef industries. His stories and photographs are featured on a dedicated National Geographic blog for the program, as well as on the National Geographic food blog, The Plate.

Continuing Relevance

At various points in its 70-year history, the Fulbright Program has faced funding challenges, notably in the aftermath of the Cold War. In the early 1990s, policymakers hoped to take advantage of a “peace dividend,” leading to cuts in Fulbright and other programs supported by the former U.S. Information Agency. There was an initial assumption that the fall of the Soviet Union had lessened one of the most compelling needs to promote mutual understanding abroad. But the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, as well as increasing global interdependence, have re-minded us that people-to-people exchanges remain essential to fostering peace, stability and shared prosperity.

In recent years, despite tight budgets across the federal government, the Fulbright Program’s funding has remained steady, with an annual congressional appropriation of more than $200 million—reflecting strong bipartisan support and acknowledgment of the continuing relevance of the Fulbright mission. The program also receives more than $130 million from other sources, making it one of the most highly leveraged programs in the U.S. government; for every two U.S. government dollars invested, Fulbright attracts more than a dollar in other resources.

To plan the program’s future, the State Department is in the process of evaluating how different audiences and constituencies view it. State is also working to strengthen outreach to key stakeholders and potential applicants.

Fulbright alumni almost invariably describe the program as “life-changing” and “transformative,” and many of them have gone on to distinguished careers in government, science, the arts, business, philanthropy and education around the world. Generations of public diplomacy-coned U.S. Foreign Service officers have been instrumental in building, promoting and sustaining the program in the field.

As the Fulbright Program marks 70 years of achievement, we present several personal reflections from alumni who became FSOs.

Personal Stories from FSO Fulbright Alumni

BERLIN, 2002–2003, COLLEEN TRAUGHBER

Colleen Traughber during her Fulbright year in Germany.

Courtesy of Colleen Traughber

I arrived at the Otto Suhr Institute of Political Science at the Free University of Berlin in the fall of 2002 with a Germany-centered project—and left a year later with a much broader perspective and an interest in the Foreign Service. My actual project was to study German identity and analyze how it was being influenced by the ongoing enlargement of the European Union. But practically from my first days there, I was swept up in a student movement protesting U.S. policy toward Iraq and the impending invasion (“Kein Krieg gegen den Irak!” = No war against Iraq!) complete with leaflets, signs, information booths and organized discussions.

During the months leading up to the March 2003 invasion, I researched the U.S. debate over Iraq during my internship at the German Council on Foreign Relations. Once the invasion of Iraq began, I joined the Trans-Atlantic Student Forum, a network of university students in Berlin from both sides of the Atlantic, and authored a piece with the group on the differences between European and American security cultures. I later joined a fellow German student to organize a town hall and panel discussion at the Free University on “German-American Relations in a Time of Terror.”

I concluded my time in Berlin with an internship at the German Parliament (Bundestag), where I was privy to key discussions on German foreign policy. It was a critical moment in trans-Atlantic relations, and it was clear that we needed as much conversation and exchange of ideas as possible to maintain the relationship.

My experience in Berlin exposed me to different perspectives on foreign policy. It encouraged me to consider the importance of our European partners, including Germany, and taught me that the trans-Atlantic relationship is not imperishable.

Finally, it impressed on me the importance of global citizenship and approaching world affairs from multiple perspectives. It thus set the stage for my future work in the Middle East and Europe, and sparked an interest in multilateral affairs.

My Fulbright experience in Germany also introduced me to the Foreign Service as a career path. I met my first Foreign Service officer, Richard Schmierer, at a Fulbright event in Berlin. Then minister-counselor for public affairs, he not only served as a resource for me on the Foreign Service (answering every one of my emails!), but also included me in a public affairs outreach program to German schools after the Iraq invasion.

After all these experiences, I was hooked on becoming a diplomat.

BELFAST, 2001–2002, JEROME SHERMAN

In September 2001, just a few months after I graduated from college, two events took place that set me on the path to becoming a Foreign Service officer. The first was a phone call from London, telling me that I had received a grant from the U.S.-U.K. Fulbright Commission. I’ll never forget hearing that posh British accent on my answering machine. I listened to the recording a dozen times to make sure I wasn’t imagining it. The Fulbright grant was going to pay for me to study international relations at the Queen’s University of Belfast in Northern Ireland.

This had been a dream of mine since I took a three-day trip to Belfast a few years before. It was the first time I had seen a society divided by religious or ethnic conflict. British soldiers patrolled the streets. The Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods of West Belfast were divided by a 20-foot-tall barrier called the “peace line.” On both sides of the barrier, local residents had painted massive murals of masked, gun-toting paramilitaries. This world fascinated me. I wanted to understand why a people who shared a common ancestry with me were so bitterly divided. So I applied for the Fulbright grant; and, in September 2001, I was getting ready to return to Belfast when the second event occurred.

Once best known for its awards to U.S. artistic luminaries, the program now also makes about 30 percent of its awards in scientific fields.

On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, I was asleep in my parents’ house in Queens, New York City, when the phone rang. It was my mother, calling from her office in lower Manhattan. “Jerome, a plane just struck the World Trade Center,” she told me. A short while later, as the twin towers were collapsing, my mother and her colleagues—and thousands of others—fled Manhattan on foot, crossing the Brooklyn Bridge. The bridge shook, as if there had been an earthquake. Everyone close to me survived. But so many others were not as fortunate. About 90 people from my community in Queens died that day, including many police officers and firefighters.

I had been scheduled to depart for Belfast on Sept. 15. But how could I leave behind my family, my community, when we were at war? My family was unequivocal, however: I had to go. I had worked so hard for this opportunity.

So I went to Belfast, and I studied the U.S. government’s role as a mediator in the Northern Ireland conflict and contrasted it with our efforts to broker a peace agreement in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The Fulbright Program opened the world to me at a time when that world—and the U.S. role in it—were changing dramatically. I developed a lifelong commitment to understanding why we as humans are capable of inflicting such pain and suffering on each other, and what we can do to change that.

After a seven-year career as a journalist, I joined the State Department in 2010. I first served in Ciudad Juarez and then went to Jerusalem, where I worked on people-to-people pro-grams that brought together Palestinian and Israeli youth. Until July of this year, I was a special assistant in the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, in the office that oversees the Fulbright Program. It has been a great privilege to work on the very program that set me on this path, helping another generation of Americans and people from other countries to benefit from the vision of Senator J. William Fulbright.

AUSTRALIA, 2011–2012, MARVIN ALFARO

Marvin Alfaro and his colleagues on a boat in the Antarctic Ocean, with penguins splashing in the foreground.

Courtesy of Marvin Alfaro

The Fulbright Program introduced me to the world of diplomacy, giving me a platform to collaborate and exchange research project ideas with renowned Australian scientists.

In 2011, I was awarded a grant to study the impact and implication of the movement of a particular ocean boundary located in the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean) and its effects on wind patterns and earth’s climate. My research goals were to combine remote sensing data of ocean temperatures from satellites with high-resolution data retrieved as part of a marine science research team.

I had the opportunity to live onboard Australia’s Aurora Australis icebreaker for about five weeks as we traveled from Tasmania into the Southern Ocean and on to Antarctica, the earth’s coldest, driest and windiest continent. I witnessed firsthand the importance of international cooperation for the safety and security of our environment, and saw the urgent need for diplomacy to address some of the world’s biggest and most complex problems.

A few months after my arrival in Australia, the U.S. ambassador hosted a welcome reception for all American Fulbrighters in Canberra. This was the first time I had ever entered an American embassy, and the first time I had interacted with American diplomats. Throughout my year, I was in awe as I learned about the range of topics on which our two countries collaborate. So while I pursued my dream of becoming an expert environmental scientist, I found myself increasingly intrigued by the idea of building a “bridge of knowledge.”

This was a way to embrace my scientific background while also crossing into policy analysis and development in international affairs, with the ultimate goal of preparing myself to join the Foreign Service. The Fulbright Program strongly influenced my decision to pick public diplomacy as my cone. I hope to advance the State Department’s educational and cultural exchange programs, and to contribute to environmental preservation and climate change awareness through public outreach initiatives.

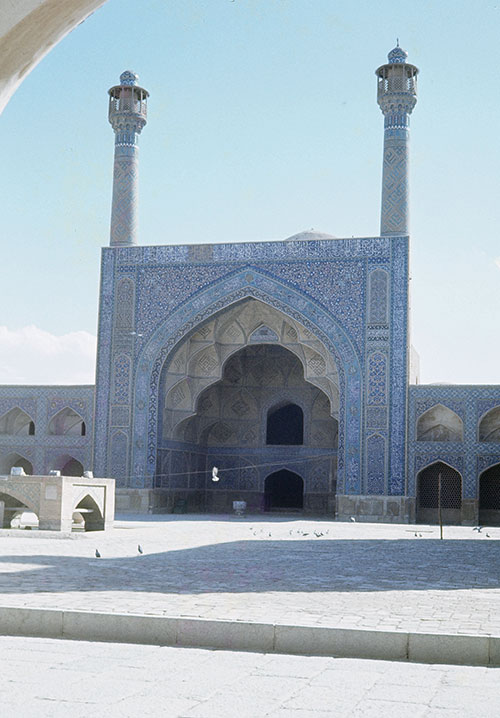

TEHRAN & CAIRO, 1977–1980, MARTIN QUINN

Shah Mosque in Isfahan, shown here, was renamed Imam Mosque after the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Martin Quinn spent his first Fulbright year at Tehran University, but transferred to Egypt in late 1978 when it appeared that Iranian universities would close.

Courtesy of Martin Quinn

Had it not been for an extended Fulbright experience in Iran and Egypt, I would never have joined the U.S. Foreign Service. It was not until my early 30s—when I received a Fulbright lectureship in American civilization (1977-1980)—that I began to think of the Foreign Service as a career. The program profoundly furthered my late-blooming interest in the Middle East, and the Foreign Service was the logical, practical way to pursue that passion.

My first Fulbright year was spent at Tehran University, an activist campus, in the fluid situation that would soon spark the Iranian Revolution. During my second year, 1978-1979, the country began lurching through the dramatic stages of a massive internal upheaval that would have far-reaching implications. Teaching and anything resembling normality became less and less feasible as the atmosphere turned more heated, xenophobic and anti-American. In late 1978, when it appeared Iranian universities would close for an extended “revolutionary holiday,” I was offered the choice of returning to Pennsylvanie State University or transferring the Fulbright grant to Korea or Egypt. I chose Egypt.

Fleeing an Islamic revolution, I wound up a midyear guest lecturer at an Islamic seminary, the oldest, continuously operating institution of higher education in the Muslim world, Egypt’s renowned Al Azhar University (established in 969 A.D.). Egypt was in the post-Camp David period, when Americans were popular and Egyptians hoped for better days following the conclusion of a decades-old conflict with Israel. My Egyptian, Lebanese, Palestinian, Sudanese, Maldivian, Albanian and Yugoslav students became my teachers, and I stayed a third year on the Fulbright in Cairo.

In May 1983, I entered the Foreign Service as a junior officer trainee with the U.S. Information Agency. But I remained involved with Fulbrighters through post-run programs in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Iraq, serving as a Fulbright Commission board member in Israel and Turkey. During my first stateside tour of duty (1995-1999), I became branch chief for academic exchanges in North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, with oversight of eight Fulbright Commissions. And two years after retiring from the Foreign Service in 2011, I was privileged to spend six months as acting deputy executive director of the Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board staff.

My Fulbright experience affected my life in ways that, even now, I have not fully absorbed.

As an FSO for 28 years, serving mainly in the Middle East, I regularly asked Fulbrighters their views of what was happening in our host country, for I had learned that diplomats inevitably have a different slant. Thirty-nine years after setting off for Iran on a Fulbright, I have never lost the conviction that the Fulbright Program, founded by an Arkansas senator who recognized the transformative effects of his own overseas educational experience, is one of the most inspiring efforts that U.S. taxpayers support.

SIERRA LEONE, 2010-2011, APRIL CONWAY

April Conway with Kambama village women who are preparing rice flour for a celebration in Sierra Leone.

Courtesy of April Conway

My path to becoming a Foreign Service officer began in 2010, when I traveled to a remote river island located in southeastern Sierra Leone. I was setting out to conduct my dissertation research on the endangered pygmy hippopotamus, an animal notoriously difficult to study in the wild. Armed with remote-sensing camera traps, my goal was to capture pygmy hippos on film to learn more about their secret lives.

My time in West Africa was made possible because of the Fulbright Program. In 2009, while I searched for funding for my project, a fellow student discussed her recent Fulbright re-search and encouraged me to apply. Less than a year later, I was on a flight to Sierra Leone as a Fulbright U.S. Student Program research grant recipient.

Both the highest and lowest points of my experience involved Embassy Freetown. Along with my basic biological research, the Fulbright Program gave me the opportunity to partner with the embassy to create environmental conservation murals with local residents in four communities. Residents enjoyed identifying the elements of the murals, and communities were proud of their newly installed artwork.

On completion of the project, I hosted Ambassador Michael Owen at my research site, where he and several staff members spent a night in the rainforest. It was a night to remember, with dancers and magicians entertaining us until late and a special appearance by a pygmy hippo “dancing devil” from the local community.

While pygmy hippos and diplomacy may not seem to have much in common, the lessons I learned as a Fulbrighter have followed me into my new career.

The lowest point of my experience was the morning I was robbed of all my belongings at a bus station in Freetown. Consular officers helped me through this difficult period. The work of those officers and others at the embassy inspired me to start thinking about the Foreign Service as a possible career.

While pygmy hippos and diplomacy may not seem to have much in common, the lessons I learned as a Fulbrighter have followed me into my new career. I learned to work better with different cultures, to maintain a sense of humor even in difficult situations and to manage resources efficiently. I also felt drawn to a life of public service.

My Fulbright experience allowed me to interact with and influence hundreds, if not thousands, of people in Sierra Leone. Now, as a Foreign Service officer, I have the opportunity to help people all over the world, both foreign nationals and Americans.

Read More...

- “Fulbright Alumni” (Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, Department of State)

- “Save Fulbright”

- “Fulbright Programs” (Benefits.gov, run by the State Department)