GPC—Meaningful Concept or Misleading Construct?

In this thought piece, two Senior FSOs offer contrasting takes on the phrase widely used to frame foreign policy today.

BY ALEXIS LUDWIG AND KELLY KEIDERLING

TAKE ONE

GPC: National Security Strategy’s “Deep Structure”

BY ALEXIS LUDWIG

The reemergence early in the 21st century of so-called “great power competition” (GPC) as the central organizing principle for U.S. engagement with the world is yet another instance of there being nothing new under the sun. It amounts to the resurfacing of what might be called the “deep structure” of national security strategy, a structure that has shaped and informed much of the conduct of international relations throughout history. GPC has expressed itself in diverse forms—with different players competing in different ways in different parts in the world—but it has never really gone away.

The great power competition of today is characterized by the dramatic rise of Xi Jinping’s People’s Republic of China as a peer competitor of the United States and, to a lesser extent, by the revanchism of Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Napoleon’s Delphic prophecy is telling from the vantage point of our own time: “When China rises, the world will tremble” (Quand la Chine s’éveillera, le monde tremblera). The slow-moving shock waves associated with China’s undeniable rise and accompanying geopolitical assertiveness are a manifestation of competition that is already well underway.

A Constant in History

“Great power competition” made its inaugural appearance in the first formal work of Western history ever written. In History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides describes the prolonged competition and clash between the city-states of Sparta and Athens more than 2,500 years ago. Closer to our age, full-blown great power competition flowered in Europe in the early 19th century when Napoleon’s France took the continent by storm, overreached and then was forced into retrenchment by its great power rivals Britain, Russia and Prussia. Following the unification of German states under Bismarck, World War I and World War II reflected, at the most fundamental level, the reverberations of great power competition between a rising Germany and its continental rivals, most notably France, Britain and Russia. The world wars also marked the definitive rise of the United States as a new great power on the block.

The Cold War, which remains the central geostrategic reference for the baby boomer generation in power today, was characterized by the U.S.-led democratic West against the Communist East bloc, led by the Soviet Union. That Moscow explicitly sought, as a matter of ideology and policy, to destroy the Western system and to replace it with global communism, turned Cold War GPC into a kind of life-or-death struggle that shaped nearly every aspect of our engagement with the world.

The collapse of the USSR and the emergence of the so-called “new world order” saw the United States suddenly—and temporarily—thrust into the role of sole remaining superpower. In the absence of clear great power competition and, by extension, a clear set of strategic priorities, it became a time for recalibration and reconfiguration—more disorder than order. The 9/11 terror attacks unleashed the “global war on terror,” which played a stopgap role in organizing our global engagement for the balance of this transition.

Reemergence of Overt Great Power Competition in the 21st Century

China’s rise as a comprehensive peer competitor of the United States became an incontrovertible fact with the ascension of President Xi Jinping to power in 2013. Xi ended China’s long era of low-profile strategic patience (the so-called “peaceful rise”), unmasking Beijing’s broader ambition to equal and even to overtake the United States across all dimensions of power by 2049. China’s deeply ambivalent approach to the U.S.-led liberal international order—using elements of that order to achieve its more narrow national aims, while also building parallel structures of its own—only reinforced the fact that GPC was upon us. At the same time, Russia’s provocative behavior as a wounded power intent on reasserting its sphere of influence, undermining the liberal international order and harassing the United States and its allies, signaled a broader reversion to historical mean.

Former President Donald Trump’s 2017 National Security Strategy marked an overt, even bare-knuckled recognition of this fact. The document described a “competitive world” in which “China and Russia challenge American power, influence and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity. They are determined to make economies less free and less fair, to grow their militaries, and to control information and data to repress their societies and expand their influence.” The NSS further emphasized: “The competitions and rivalries facing the United States are not passing trends or momentary problems. They are intertwined, long-term challenges that demand our sustained national attention and commitment.” Whatever one’s view of the nuances and subplots, GPC had returned in earnest.

China’s rise as a comprehensive peer competitor of the United States became an incontrovertible fact with the ascension of President Xi Jinping to power in 2013.

The Biden administration is unlikely to alter this underlying structure, even as it seeks to open the strategic aperture to include critical global issues—climate change being the central one—that will require great power cooperation as well as competition. This is because there is now broad consensus across the U.S. political spectrum about the implications of China’s rise and Russia’s continuing effort to find its footing after the breakup of the USSR, and the challenges they (separately and together) pose to the liberal international order, in particular, and to democracy and freedom more broadly.

The Biden administration’s Interim National Security Strategic Guidance document, published in March, underscores this basic policy continuity: “China, in particular, has rapidly become more assertive. It is the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system. Russia remains determined to enhance its global influence and play a disruptive role on the world stage.”

Summing up, the Biden strategic guidance document proceeds to set forth an agenda that “will strengthen our enduring advantages and allow us to prevail in strategic competition with China and any other nation.”

GPC as Artifact, Frame and Spur to Action

Whatever the historical context, “great power competition” is an artifact of human political imagination, not a manifestation of political geology or nature. It is anchored in an assessment about what matters most to the survival, well-being and interests of a state, or what ought to. This assessment and the decisions that flow from it are intended to shape and inform national strategy—to ensure that national efforts, resources and instruments of power are orchestrated and directed to core priorities based on a clear calculation of national interests.

It is important to emphasize here that great power competition does not necessarily mean great power confrontation or conflict. That, too, is a political choice, not a historical inevitability. Moreover, competition itself is a great engine of human motivation, effort and accomplishment. The United States has enthusiastically embraced competition as a core value and ideal across nearly all spheres of human activity. Competition compels us to work harder and smarter, with a keener focus and a clearer objective in mind, enabling us to achieve greater things than we might have done in the absence of worthy competitors.

Would we have marshalled the kind of concerted collective effort needed to “land a man on the Moon and bring him safely back to earth” were it not for the Sputnik challenge in the context of Cold War competition with the Soviet Union? Might we expect similar positive results from the great power competition with China unfolding today? If not, why not?

While it is wise to avoid Pollyannaish thinking, it is equally unwise to bet against the United States of America. Whatever the vulnerabilities of our more open democratic system and the advantages of our competitors’ centrally controlled autocratic alternatives, this is a time to double down on our strengths: more open, free-wheeling and democratic, more resilient and resourceful, more innovative, nimble and able to adapt to new threats and opportunities. This is a time to become—as journalist James Fallows argued in a related context just over a generation ago—“more like us.”

GPC is a useful frame to engage the world collectively for constructive benefit, repelling threats and seizing opportunities. But if there’s a more useful one, we should welcome it.

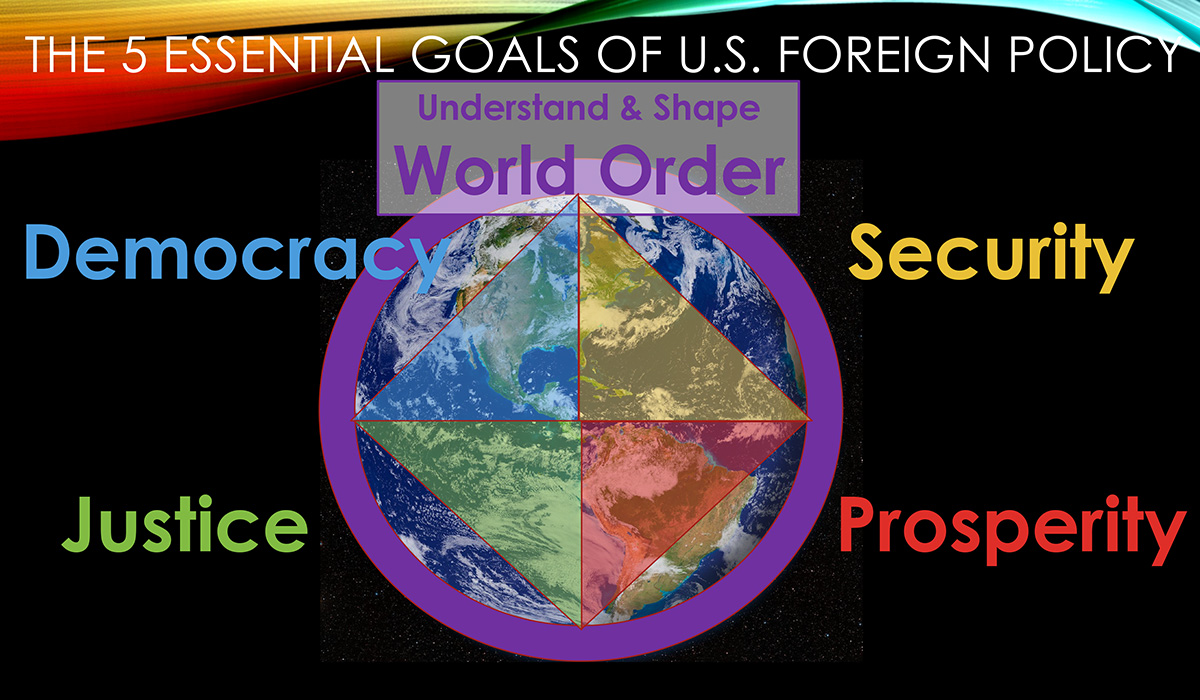

Ambassador Kelly Keiderling uses this “foreign policy wheel” to identify the five essential U.S. foreign policy goals since World War II.

COURTESY OF KELLY KEIDERLING

TAKE TWO

“Great Power Competition”: A Phrase that Simplifies and Confuses

BY KELLY KEIDERLING

At least since President Donald Trump issued his National Security Strategy in December 2017, the national security community has been obsessing about great power competition (already shortened to GPC). GPC is framed as a great-power struggle mostly with the People’s Republic of China, with Vladimir Putin’s Russia participating as a spoiler.

GPC is a comfortable frame for the baby boomer leaders across our interagency community who began their careers during the Cold War. It is an elegant frame for the grand strategists who want a unified theory of everything. It is a favorite of our academic and practitioner colleagues whose principal foreign affairs lens is realpolitik, the balance-of-power geopolitics in which great powers throughout history have maneuvered to gain more security and prosperity at the expense of other great powers. GPC also works as clarifying shorthand for American compatriots who have little time for foreign affairs and who may be more easily galvanized to support international competition against the PRC.

GPC is a simple slogan for understanding international relations, but it confuses more than it clarifies. On the “forever” front in which our State Department lives—that international horizon that exists whether Americans are paying attention or not, that perpetual-motion machine of sovereign states, international organizations and nonstate actors—the world is much more complex.

The World Is More Complex

So much of our State Department’s work doesn’t fit neatly into competition with the PRC (and Russia, which is often included in the GPC framework). Our engagement in the Western Hemisphere has the most impact on the average American’s security and prosperity, regardless of the PRC’s presence in our hemisphere. The African continent is moving fast into its future, powered by young, professional Africans. We want to partner with those dynamic Africans, regardless of how many infrastructure projects the Chinese build on the African continent.

Our European, Japanese, South Korean, Australian, New Zealander and Canadian allies are important not just to counterbalance the PRC but also, mostly, because those alliances form the bedrock of American security and prosperity and the engine for making this world more democratic and just. If our international relations are defined by “Are we beating the Chinese in Africa?” we will tell our partners around the world that they hardly matter unless the PRC is making them an offer. We will miss a great number of opportunities to advance U.S. interests and values. Our allocation of national security resources will be weighted toward anything-PRC. Our foreign affairs work is just not reducible to competing with the PRC and fending off malicious Russian designs.

Besides, GPC describes a dialectical process, not a strategic goal. GPC is about the United States accumulating raw economic, military and cultural power: economic output, volume of international trade and investment, size and reach of armed forces, number of patents and number of entertainment products, media outlets and footprint of U.S. Big Tech, for example. Concerned about balancing the PRC’s economic might, the U.S. then needs to convert our raw power into global influence to—what, precisely?—perhaps to become even more powerful, to be perceived by other great powers as more powerful, to increase the prestige and standing of the United States. How do we measure that power? When can we stop accumulating power? When is U.S. global influence and prestige sufficient? When have we been successful in our competition with the PRC?

Focus on U.S. Strategic Goals

We need a lens focused on U.S. strategic goals rather than on GPC. Toward that end, I offer a “foreign policy wheel” to help frame broad U.S. foreign policy goals. I propose that, since World War II, to a greater or lesser extent, the United States has advanced on five essential foreign policy goals: 1) understanding global affairs and creating a world order based on rules, 2) increasing U.S. security, 3) enabling U.S. prosperity, 4) advancing democracy, and 5) defending human rights and helping create more just, equitable human societies.

For each country, for each region, let us create dynamic strategies with specific, more measurable foreign policy goals that address the most pressing of these five goals. For Southeast Asia, primary U.S. goals would include (among others) freedom of navigation through the South China Sea, improved democratic governance in the Philippines and economic partnership with Vietnam. In Ukraine, for example, we would focus on strengthening the country’s democracy, economy (by fighting corruption) and security against Russian intervention, in part to sustain a global order in which sovereign borders and territorial integrity are respected.

Finally, the overarching strategic threats facing humanity in the 21st century—climate change, global pandemics, an internet awash in mis- and disinformation—require cooperation with the PRC, Russia and other powers big and small. GPC will distract us from pursuing tailored policy goals more likely to yield measurable success. An obsessive focus on GPC will detract from strengthening carefully calibrated partnerships that we need with each country and international organization.

Our national security enterprise is filled with professional, dedicated, analytical public servants across many agencies. Comforting, familiar and simple as it might be for us in the interagency community to default to “great power competition” to explain our missions, let’s take the extra analytical step to explain to Congress and the American people the challenges we face on the forever front.

Let’s be more precise in explaining how we’ve converted our diplomatic, informational, military and economic power in each corner of the world to buttress a rules-based world order, to secure the U.S. from global threats, to find opportunities to increase U.S. prosperity, to advance democratic governance, and to defend human rights and foster better, more just societies.

Read More...

- “Great-Power Competition Is a Recipe for Disaster,” by Emma Ashford, Foreign Policy, April 1, 2021

- “The New Concept Everyone in Washington Is Talking About,” by Uri Friedman, The Atlantic, August 9, 2019

- “U.S.-Chinese Rivalry Is a Battle Over Values,” by Hal Brands and Zack Cooper, Foreign Affairs, March 16, 2021