The Impact of COVID-19 on FS Kids: Tips and Thoughts

FS children face unique challenges in the best of times. How are they faring during the pandemic?

BY REBECCA GRAPPO

Resources

- Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds, by David C. Pollock and Ruth E. Van Reken

- Raising Global Teens: A Practical Handbook for Parenting in the 21st Century, by Dr. Anisha Abraham

- Emotional Resilience and the Expat Child: Practical Storytelling Techniques That Will Strengthen the Global Family, by Julia Simens

- Raising Kids in the Foreign Service, by Associates of the American Foreign Service Worldwide (Author), Leah Morefield Evans (Editor)

- The Emotionally Resilient Expat: Engage, Adapt and Thrive Across Cultures, by Linda A. Janssen

- “Promoting Your Child’s Emotional Health,” The Foreign Service Journal, June 2011, Semiannual School Supplement, p. 73.

- International School Counselor Association Website: https://iscainfo.com

- Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence: https://www.ycei.org

- American School Counselor Association: https://www.schoolcounselor.org

Books will be written, and Ph.D. theses will be defended, about the impact of COVID-19 on society. But few will probably ever interview, let alone study, one group of people: the children of the Foreign Service.

Members of the Foreign Service are highly trained professionals who take on worldwide assignments and serve courageously amid threats of war, terrorism, natural disasters—even pandemics. Let’s take a look at how their children fare.

The Pandemic Strikes

Not many people could have imagined the seismic impact a global pandemic would have on their professional or personal lives—and especially those of their children. Far-reaching, this pandemic has affected just about every single person on the planet.

It caused a global diaspora of Foreign Service families. About 13,000 children are dependents of American diplomats in more than 230 posts around the world. Unless they were infants and blissfully unaware of what was happening, all of them have been affected.

Some families left posts under authorized or ordered departure; others stayed throughout the pandemic, but remained locked in their homes, unable to go out for months at a time. To say that it played out differently according to the country would be an understatement; experiencing the pandemic in Sweden was not the same as experiencing it in Brazil or Manila. But no matter where they were posted, no one has had it easy.

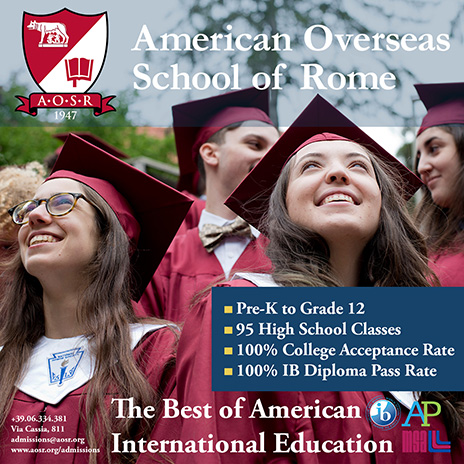

Schools began to shut down amid the growing crisis in March 2020. Students anticipated being back at school after spring break, only to find that they couldn’t return for the rest of the academic year. It would be impossible to quantify the many interrupted rites of passage and milestones missed.

In international schools, many students moved back to the United States, unexpectedly, or on to new countries. Those who did not move, the “stayers”—a term coined by child psychologist Dr. Doug Ota, who studies attachment in international school transitions—had their struggles, too, as they witnessed their friends and teachers suddenly depart, leaving them behind.

“The Washing Machine of Transition”

For many Foreign Service kids, there was no chance to say goodbye at the end of the school year, leading to a tremendous sense of loss without closure. What’s more, few students and families possessed the language to talk about transition.

As one international school counselor commented in a recent webinar for school personnel, those personnel living in the international school world were all experiencing “the washing machine of transition” at the same time their students and families were.

FS kids who were stateside at the start of the pandemic endured the sudden scramble to figure out how to put entire educational systems online, a heroic effort by teachers and administrators. Students were heroic as well, as they struggled to adapt and faced canceled games, proms, performances and other much-anticipated events.

Many counseling professionals were concerned, though, about the students’ loss of attachment to those in a school community whose role is to help kids feel safe and secure. Such a sudden transition from what was considered “normal” can expose the strengths and weaknesses of a school community, as well as be a factor in a child’s or adolescent’s resiliency.

Many boarding schools were able to create safe bubbles through quarantining, and those students had a relatively normal year. Yet many still felt the disruption, and could not reunite with their families overseas (as of this writing, some have been separated from their families for more than a year now), or faced forced quarantines on return to campus.

Academic Impact

In addition to the emotional costs, many students and families have reported that the last year has brought about other losses in academic achievement. Not only were there lost learning opportunities, but students who struggle with executive functioning or other learning differences have faced additional challenges staying on track.

The structure and extra support they have depended on have not always been available through Zoom at the level needed, leading to learning gaps. Even something as seemingly mundane as internet connectivity, which can vary widely based on where one lives, made it difficult for some families to be online for school and work remotely all at the same time.

Standardized tests such as the SAT, and even AP and IB exams, were affected, and this resulted in even greater anxiety about the college application process among many students and their parents.

Perhaps the greatest negative impact, however, was on the students who were caught moving from Country A to Country B, at times with an indefinite evacuation stop in the U.S. It has not only been extremely difficult for these students to catch up academically—and feel caught up—but also to make new friends and feel connected to the new school community.

Nevertheless, some students have enjoyed learning at their own pace and not feeling the stress of rushing to school or enduring long bus or taxi rides across traffic-clogged cities. One parent reported her son was “living his best life!”

Parents Talk About the Loss of Connection

As one parent puts it: “It’s difficult enough to be a teen moving from a comfortable and secure place, where you have a great group of friends and you know your surroundings well, to a place that is not as comfortable or as secure. But then add COVID-19 where the opportunities for kids to build relationships with other kids in the new post is almost completely absent. I think that is the biggest impact COVID-19 has had.”

Another parent shares: “PCSing [moving to a new post] is challenging always, and one of the big priorities arriving in a new post for both adults and kids is making new friends and finding community. Transitioning to a new post with a severe COVID-19 situation meant this stage effectively did not happen.”

And yet another parent serving in a country that has been particularly hard-hit writes: “I think for us and many people, the hardest thing was dealing with unknown health risks and social distancing requirements placed upon us by the pandemic. The local kids and their parents are much more permissive regarding staying out late, social distancing, etc., than we are. Thus, our son continues to struggle with his conservative parents.”

Recommendations for Parents

Many parents remain anxious about the cumulative effect of both the pandemic and the additional stressors that can come with Foreign Service life, and naturally wonder if their kids are going to be OK. Here are a few tips that other FS parents and experts have offered.

Communicate, empathize and validate your children’s feelings and concerns. Model for your children that it is OK to be sad and reassure them you are there for them. Be wary of toxic positivity—i.e., being overly positive without acknowledging the difficulty.

Ruth Van Reken, co-author of Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds, 3rd ed. (Nicholas Brealey, 2017), says it is important to offer comfort before encouragement. Acknowledge the pain, loss and disappointment of the past year so that they feel seen. Then the words of encouragement can follow.

It would be impossible to quantify the many interrupted rites of passage and milestones missed.

Provide the language your children and teens need to describe their emotions and what’s going on. An excellent book for elementary-age children is Emotional Resilience and the Expat Child by Julia Simens (Summertime, 2011).

Use your school counseling team as a resource. Communicate with the school counselor if you are encountering difficulty at home. Ask if they have resources for helping to develop social-emotional intelligence and resilience. What can you reinforce at home? The International School Counselor Association has been developing resources, so encourage your school to become a member if it has not already.

Encourage your children to practice the pillars of good health—sufficient quality sleep, proper nutrition and exercise—and maintain structure in daily life.

Be creative in celebrating rituals at home and recognizing milestones. These may become some of your most cherished memories.

If the plan changes, allow your children to deviate from their intended path, if needed. It might be healthy to reassess the plan. Does that mean switching schools? Taking a gap year? Changing their college plans? Help them to think it through and then offer support.

Help your kids to see the future and know that this period is not going to last forever. Encourage them to think and plan for future events such as travel, college, and time with loved ones.

Recommendations for the Department of State

Some parents have also offered their suggestions for how the department can better support families during this time.

Find ways to support parents. Whether employees or not, all parents are juggling a lot right now. It might be working across time zones, fulfilling professional obligations while simultaneously needing to help (multiple) kids with online learning. Single parents, in particular, have shouldered huge responsibilities.

The Department of State Standardized Regulations (DSSR) was written for “normal” times, not a pandemic. When possible, give the most generous possible interpretation to a regulation if it will help to support students and their families. Find a way to say yes, and if you can’t, then explore and act on how to change the regulation.

Travel allowance. Parents who send their children back to boarding school face the decision to have their children travel solo, or (since all are not able to travel alone) accompany them. Boarding schools now have new quarantine requirements, at times requiring a hotel stay off-campus. There is no allowance for this.

Education allowance. If families determine it is in the best interest of their child to repeat a year because of the learning difficulties accrued during the pandemic, find a way for the education allowance to cover it. Parents and their children do not make such decisions lightly—trust them.

Stories of Resilience

Dr. Robert Brooks, a psychologist who has spent his career researching resilience in kids, states that “islands of competency” can be a great predictor of flexibility and tenacity in young people.

That is, do they have hobbies and interests they can pursue? Where do they excel? Do they have a portable skill or talent that allows them to connect with others? Is there a way to translate their favorite extracurricular activity into something that works even in a pandemic?

Stories abound of FS students who have led clubs and organizations in schools, performed theater and musical ensembles online, created studio art projects, engaged in service projects and political activism, raised money for those in need, volunteered, stepped up to help out family members, took courses online, learned a new skill, got paying jobs or internships—and more.

Though the pandemic created personal challenges our kids have never experienced before, the way so many have persevered and risen to the occasion is nothing short of inspirational.

Read More...

- “Pandemic Parenting—How Foreign Service Moms Are (Not) Making It Work,” by Donna Scaramastra Gorman, The Foreign Service Journal, April 2021

- “COVID on Campus: How FS College Kids and Their Families Are Managing the Uncertainty,” by Donna Scaramastra Gorman, The Foreign Service Journal, December 2020

- “Luanda to Ohio: A Family Journey,” by Monica Rojas, The Foreign Service Journal, July-August 2020