A Life of Significance: An Interview with Deputy Secretary of State William J. Burns

On the eve of his retirement, the Deputy Secretary of State reflects on his 33-year career, the challenges for diplomacy today and the future of the Foreign Service.

BY ROBERT J. SILVERMAN AND SHAWN DORMAN

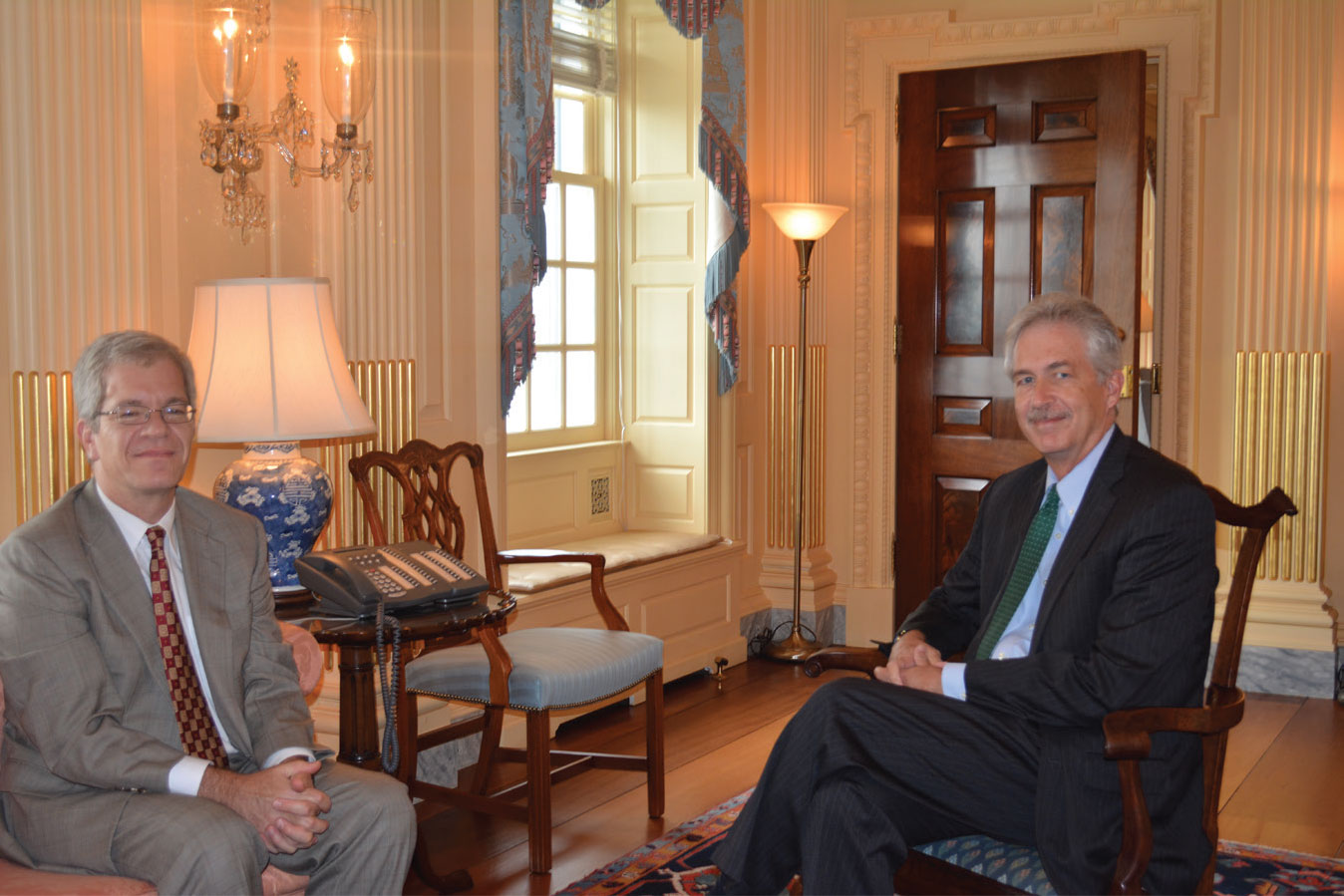

On Oct. 1, 2014, then-AFSA President Robert Silverman and Foreign Service Journal Editor Shawn Dorman sat down with Deputy Secretary of State William J. Burns in his office, a few weeks before his retirement from a 33-year Foreign Service career. Ambassador Burns holds the highest rank in the Foreign Service, career ambassador. He became Deputy Secretary of State in July 2011, only the second serving career diplomat in history to do so.

Amb. Burns served from 2008 until 2011 as under secretary of State for political affairs. He was ambassador to Russia from 2005 until 2008, assistant secretary of State for Near Eastern affairs from 2001 until 2005 and ambassador to Jordan from 1998 until 2001. He has also served in a number of other posts since entering the Foreign Service in 1982: executive secretary of the State Department and special assistant to Secretaries Warren Christopher and Madeleine Albright; minister-counselor for political affairs at the U.S. embassy in Moscow; acting director and principal deputy director of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff; and special assistant to the president and senior director for Near East and South Asian affairs at the National Security Council.

Amb. Burns earned a B.A. in history from LaSalle University and M.Phil. and D.Phil. degrees in international relations from Oxford University, where he studied as a Marshall Scholar. He is the recipient of three honorary doctoral degrees. Amb. Burns is the author of Economic Aid and American Policy Toward Egypt, 1955-1981 (State University of New York Press, 1985).

He speaks Russian, Arabic and French, and is the recipient of three Presidential Distinguished Service Awards and a number of Department of State awards, including two Secretary’s Distinguished Service Awards, two Distinguished Honor Awards, the 2006 Charles E. Cobb Jr. Ambassadorial Award for Initiative and Success in Trade Development, the 2005 Robert C. Frasure Memorial Award for conflict resolution and peacemaking, and the James Clement Dunn Award. In 1994, he was named to Time magazine’s list of the “50 Most Promising American Leaders Under Age 40” and to Time’s list of “100 Young Global Leaders.”

Amb. Burns joined the American Foreign Service Association in 1982, the year he joined the Foreign Service. He has been a great supporter of the organization ever since.

—Shawn Dorman, Editor

AFSA President Robert J. Silverman interviewed Deputy Secretary of State William J. Burns at the Department of State on Oct. 1.

AFSA / Shawn Dorman

Robert J. Silverman: Bill, thanks for your support of the Foreign Service and AFSA over the years. It’s been really tremendous. Looking back over a career spanning 33 years, can you give us some of your highlights?

William J. Burns: First, it’s very nice to see you both. I’ve been extraordinarily fortunate over nearly 33 years in the Foreign Service, and had wonderful opportunities and terrific people to work with. I realize how lucky I’ve been.

Within my first decade in the Foreign Service, I worked for Secretary [James] Baker as principal deputy director of the Policy Planning Staff during what was as exciting a period in American foreign policy as any I’ve lived and worked through—the end of the Cold War, breakup of the Soviet Union, Desert Storm, the Madrid Peace Conference and the reunification of Germany. It was a combination of fascinating and transformative events in the world, and some terrific people to learn from, including Secretary Baker, President George H. W. Bush, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell, National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft and Larry Eagleburger, who sat in this office as Deputy Secretary of State at the time.

That was a fascinating moment in my career, from which I learned a lot. I served a few years later as ambassador to Jordan during the period in which King Hussein died after 47 years on the throne. Jordan didn’t know a world without King Hussein. It was a challenging period in which to demonstrate the commitment of the United States, of Americans, to Jordanians as they made the quite successful transition from King Hussein to King Abdullah.

I’ve loved the times I’ve worked in Russia, despite all the serious complications between our governments. It’s a big, fascinating society.

And then, I guess the last thing I’d mention as a highlight is the secret bilateral negotiations we held with the Iranians on the nuclear issue last year. We were able, first, to do something in secret, which is not easy to do in this day and age; but second, to make enough progress to help produce a first agreement on the nuclear issue, which opened the door to some greater possibilities. It’s a tall order to walk through that door. And it remains a question whether the Iranians are going to take advantage of this opportunity. But it won’t be for lack of trying on our part.

Our ability to help navigate a very complicated international landscape in the pursuit of our interests and values remains enormously significant.

RJS: I know you’ll be remaining involved in those negotiations for some time, as well. As they say in the book of Joshua: Be strong and have good courage.

You mentioned Secretary Powell and some of the other Secretaries of State. You’ve worked with an incredibly impressive group of people over the years. Can you mention two or three of the career people that stand out in your mind?

WJB: I’ve worked for 10 Secretaries of State during the course of my career, and admired and respected all of them. As I look at career role models, I think of Tom Pickering, for whom I worked in Moscow in the early- to mid-1990s, as somebody who’s always embodied for me the best of our profession. I’ve certainly learned a lot from him, not just in terms of diplomatic skill, but also in terms of decency and integrity, and the way in which he always conducted himself as a professional.

I’ve also learned a lot from people whose names aren’t always in the newspaper, both in the Foreign Service and the Civil Service. And I’ll give you two examples of spectacularly talented, if unsung, professionals in the State Department—both civil servants.

One is Jonathan Schwartz, now deputy legal advisor, who is about to retire, as well. Jonathan and I worked together on Middle East peace issues over the years. And we worked together on what were then secret negotiations with the Libyans some years ago.

And then I would mention Jim Timbie, another institutional treasure. He has been working on nuclear and arms control issues for a very long time, and I’ve worked very closely with him on the Iranian nuclear negotiations. Those are two people whose names don’t often appear in public, but I think they reflect the very best that this department has to offer.

Another superb public servant, Mary Dubose—who has put up with me off and on for a quarter-century both in Washington and overseas—is not only the finest Office Management Specialist I’ve ever worked with, but as decent and as skillful a professional as I’ve ever worked with.

And I’ve served with some wonderful Foreign Service Nationals—I date myself when I say that, I should say Locally Engaged Staff. Nadia Alami worked in public affairs at Embassy Amman and did a terrific job when I was ambassador in Jordan. But she is just one example of the many extremely talented and dedicated Foreign Service Nationals with whom I’ve enjoyed working over the years, just as you have.

Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton officiates at the swearing-in ceremony for Deputy Secretary of State William J. Burns on Sept. 8, 2011. In attendance are Burns’ wife, Lisa Carty, center, and the couple’s daughters, Sarah, far right, and Elizabeth.

U.S. Department of State

RJS: Absolutely. Let’s look for a few minutes toward the future. Taking out your crystal ball, could you just give us some general thoughts on how you see both professional diplomacy and, specifically, the U.S. Foreign Service evolving to meet current and future challenges?

WJB: The world is obviously an increasingly complicated place. Compared to the moment when I entered the Foreign Service in January of 1982, power is more diffuse in the world—there are more players on the international landscape.

Diplomacy is no longer, if this was ever the case, just about foreign ministries and governments. It’s about nongovernmental players. It’s about civil society groups and private foundations, as well as the forces of disorder, whether it’s extremists or insurgents of one kind or another.

And on top of all that, information flows faster and in greater volume than at any time before. So the challenges for professional diplomats are, I think, as great as I’ve ever seen them. But I continue to believe that our work matters as much as it ever has. Our ability to add value and to help navigate a very complicated international landscape in the pursuit of our interests, remains enormously significant. That should be a source of pride, not just for our generation of Foreign Service officers, but for succeeding generations, as well. And, fortunately, as I speak to A-100 classes and to our colleagues around the world, I am continually struck by the quality of the people with whom we work.

RJS: Yes, I agree. We were just coming from an A-100 recruitment lunch, and felt the same way, that there are incredibly talented people coming in. What would be your specific advice to the A-100 newcomers, and not just A-100, but all those in the early years of their Foreign Service career? What should they be doing to prepare for these future challenges?

WJB: First, don’t take for granted the opportunity that you have. Ours, I genuinely believe, is a life of significance. We do work that matters with some exceptionally talented and dedicated people. And that’s a rare-enough thing.

Second, I think you want to take some chances in your career, as well. Learn new things, whether it’s working in a different region, or learning a different language, or taking on a different set of functional skills. I think all of those things are going to be very important, because for the State Department, whether it be the Foreign Service or Civil Service, staying ahead of the curve is an unusually important challenge.

That’s why, as you look at issues that have been emerging in recent decades, whether it’s climate change and energy security (especially the energy revolution in this country and the opportunities strategically that that provides the United States), or whether it’s global health issues (as we’ve just been reminded in the midst of the Ebola crisis), diplomats have an extraordinarily important role to play in dealing with those kinds of challenges.

Equally important is economic diplomacy, something to which both Secretary [Hillary Rodham] Clinton and Secretary [John] Kerry have attached a lot of emphasis. One of the things I have always enjoyed most as a chief of mission is commercial advocacy, trying to ensure a level playing field for American companies overseas.

Increasingly, our own economy depends on expanding the volume of our exports, which, in turn, will create jobs here at home. Diplomats have a very important role to play in the promotion of those economic interests overseas. And so, for the new generation of officers, whatever your cone or specialization is, recognizing the significance of those economic and commercial issues is going to be increasingly important. It will also be an increasing source of professional satisfaction.

It’s the people with whom you work that are going to matter the most. Taking care of your people as you rise in seniority is extremely important.

RJS: Speaking as an economic officer, I completely agree. Another group that we talk to a lot, a group that looks to us, is college students who are interested in the Foreign Service. Do you have any specific suggestions for how they should be preparing, those who want careers in this business?

WJB: I may not be objective about this, because I’ve been extraordinarily lucky during the course of my career, but I don’t think there is any magic formula for professional satisfaction or success in the Foreign Service. I think it helps to come into the State Department with a pretty realistic sense of the pace of the career, of the value of taking some chances along the way, and ensuring that you have a broad foundation as you progress in a career, whether that’s in terms of language ability or any other kind of experience.

I think it’s important, as I said before, not to take things for granted as you go along. A career can go by very quickly. You want to appreciate the opportunity that you have to make a difference, which is what most of us enter public service in order to try and do. You want to appreciate the fact that it’s the people with whom you work that are going to matter the most. Taking care of your people as you rise in seniority is extremely important.

There are lots of people in our profession who are better at managing up and managing over than they are at managing down—leading and taking care of people. And I think that’s a quality that we need to attach great importance to, because we’re a relatively small institution, the State Department in general and the Foreign Service in particular. And therefore, our great strength is our people, and we want to make sure that we’re taking the best possible care of them.

RJS: Excellent. Can we talk about Russia a bit?

WJB: Sure.

RJS: Looking at our younger colleagues and those who are coming through the system, what advice would you give to someone who’s being posted to Embassy Moscow?

WJB: You want to invest in the Russian language, which is obviously an entry point to understanding that society. Russians are understandably deeply proud of their history and their culture. It’s important to understand what Russia as a society has been through in recent generations, going back to the Soviet period during which the population endured the famine, the purges and the Second World War.

And then there are all of the changes that have taken place since the end of the Soviet Union and the very difficult transition—promising, but very difficult—that unfolded during the period when I first served in Moscow in the mid-1990s. Whatever the difficulties in our relations—and, certainly, today we have profound difficulties with the current Russian leadership—it is important to develop a sense of respect for that history, and what Russians as a people have not only endured but also achieved.

One of the things I enjoyed the most in the two tours my family and I spent in Russia was traveling around the country. It’s a huge place. The last time I served there, there were 11 time zones. Just the expanse of it is really striking. And it’s fun too. It’s trite to say, but just as you can’t understand the United States if you just sit in Washington or New York, you can’t understand Russia if you’re spending all your time in Moscow and St. Petersburg. So it’s important and it’s fun to get out.

Deputy Secretary Burns addresses the people of Ukraine in Kyiv on Feb. 25.

U.S. Department of State

RJS: What would you say is the Peoria of Russia? What is your favorite heartland place?

WJB: Well, there are lots of different places to point to, like Siberia with its vast expanse. And there are fascinating cities in the Urals, like Yekaterinburg. I’ve always enjoyed the Russian Far East, as well as the far north, which is a tough place to live, and not an easy place to visit sometimes. But again, it’s a reminder of the sheer expanse of that society. None of that necessarily makes political relations any easier.

And Russia, as my colleagues who are there now know, can be a very tough place to serve sometimes. But it can also be a very rewarding place, especially if you keep a sense of perspective and you understand not only the sweep of Russian history, but the continuing significance of Russia and U.S.-Russian relations.

RJS: Well, let’s take out your crystal ball again. How do you see, realistically, our relations with Iran evolving? What would you predict, say, five, 10, even 20 years from now? How will they look?

WJB: My powers of prediction, as I often demonstrate, are pretty limited.

We’ve made a start in the nuclear negotiations, building on the formerly secret bilateral talks, and working closely with our partners in the P5+1 [United States, Russia, China, Britain and France, plus Germany]. I would be the last to underestimate the difficulties that lie ahead in the negotiations. There are still significant gaps, and we’re going to keep working hard at it.

I think it’s still possible to reach an agreement that could help open up wider opportunities in the relationship, especially between our two societies. In many ways, the last 35 years of estrangement and of truly profound differences between the Iranian leadership and the United States have been unnatural, in the sense that you have had such a disconnect between our two societies during that time.

And especially for the younger generation of Iranians, I think there’s a thirst for connection with the rest of the world. That doesn’t make Iranians any less proud, any less committed to what they see to be their national goals. But I would hope that over time some of that estrangement can ease.

On the nuclear issue, I think it would be very much in the interest of Iran to reach a comprehensive agreement to demonstrate the exclusively peaceful nature of its nuclear program, and to demonstrate its commitment to living up to its international obligations. That can open up very substantial economic opportunities. I’m convinced there are lots of Iranians who could take full advantage of that, because it’s a very entrepreneurial society full of talented human beings.

RJS: So you’re not volunteering to open an embassy in Tehran, or overseeing that anytime soon?

WJB: There are a lot of obstacles that lie ahead, but I do think you have to keep focused on what’s possible down the road.

RJS: What diplomatic lessons would you draw from our experience as a country with 9/11? Particularly our experience in the Foreign Service working in Iraq and Afghanistan—how do you think that experience plays out in the future?

WJB: For a whole generation of our colleagues in the Foreign Service, the experiences of Iraq and Afghanistan in the more than a decade since 9/11 have been hugely formative. The caricature of diplomacy has always been about foreign ministries dealing with foreign ministries, a very orderly process of governments dealing with governments.

But the truth is that whether it’s in Iraq or Afghanistan, or a number of other very complicated places around the world, what the Foreign Service and the generation that came into the Service in the last 10 to 15 years have experienced is really how you conduct diplomacy amidst disorder—whether it’s a post-conflict situation or dealing with a whole range of actors, of which fully formed governments are only one. We learn how to work effectively with lots of other parts of the U.S. government, whether it’s the military, other agencies that are active overseas or our development colleagues.

And all of that has helped to create some really important skill sets in this generation of Foreign Service officers, which I think are going to be very valuable, even if I don’t believe we are necessarily going to repeat having hundreds of thousands of U.S. ground troops overseas or embarking on the kind of massive nation-building exercises we undertook in Iraq and Afghanistan.

If you look at the world, you have to conclude that in the coming generation, the forces of disorder are going to be as challenging as we’ve seen them over the last 10 or 15 years since 9/11. And so, for our colleagues, learning to navigate effectively in that kind of a world is extremely important.

The fundamentals remain the same—foreign language, curiosity, adaptability, integrity and honesty; a respect for foreign cultures and other societies; and understanding, as I said before, how to navigate them. And then, not least, knowing where you’re from—having a clear sense of American purpose.

In my experience overseas, I’ve seen that we get a lot further through the power of our example than we do by the power of our preaching.

RJS: Right.

WJB: Another reason I’m impressed by the current generation of Foreign Service officers is their diversity. I’m impressed when I see the range of experiences in the A-100 classes, not to mention diversity of ethnicities and gender. I wouldn’t say these issues have been overcome, because we still have a long way to go, but I think we’re making progress. And that’s important.

In my experience overseas, I’ve seen that we get a lot further through the power of our example than we do by the power of our preaching. When you see a Foreign Service that looks like the United States, and which is the kind of living embodiment of tolerance and diversity, I think that sends a much more powerful message to the rest of the world.

In that sense, too, I think the experience through the last 15 years or so has been important because we have evolved. We’ve got a long way to go, but I think we’re at least pointed in the right direction.

RJS: Do you feel that the Foreign Service is prepared to do this Iraq and Afghanistan type experience in the future again, in addition to traditional state-to-state diplomacy?

WJB: I think we’re learning about how to serve in the often disorderly world of the 21st century. We’ve still got a ways to go. There’s some hugely important issues, like how to manage risk. We’ve sometimes learned very painful lessons. There is no such thing as zero risk in the work that we do overseas.

We can’t connect with foreign societies unless we’re out and about. But making those judgments about what’s a manageable risk, and what isn’t, is increasingly difficult. So we’re still wrestling with a lot of those kinds of challenges, as well. I do think we’ve learned a lot. As a Service, we’re better positioned to deal with those types of challenges than was the case a decade or so ago.

RJS: Great. Let me just say, truly, thank you for everything you’ve done for AFSA and for the Foreign Service. As you said, it’s about the power of the example. And the power of your example is very important to the Foreign Service.

WJB: You’re really kind. It has been a great run. I’ve really enjoyed it.

Read More...

- Deputy Secretary of State Bill Burns is Retiring. Really, he is. (Washington Post, Oct. 2, 2014)

- The White House’s Secret Diplomatic Weapon (The Atlantic, April 4, 2013)

- 10 Parting Thoughts for America’s Diplomats (Foreign Policy article by William Burns, Oct. 23, 2014)

- Diplomat Who Led Secret Talks with Iran Plans to Retire (The New York Times, April 11, 2014)

- An Interview with William J. Burns, Deputy U.S. Secretary of State (The Politic, Aug. 17, 2013)

- William Burns Keynote Address: Samuel W. Lewis Memorial Symposium (The Washington Institute, Sept. 24, 2014)