An Unusual Expression of Gratitude

An Unusual Expression of Gratitude

BY EDWARD PECK

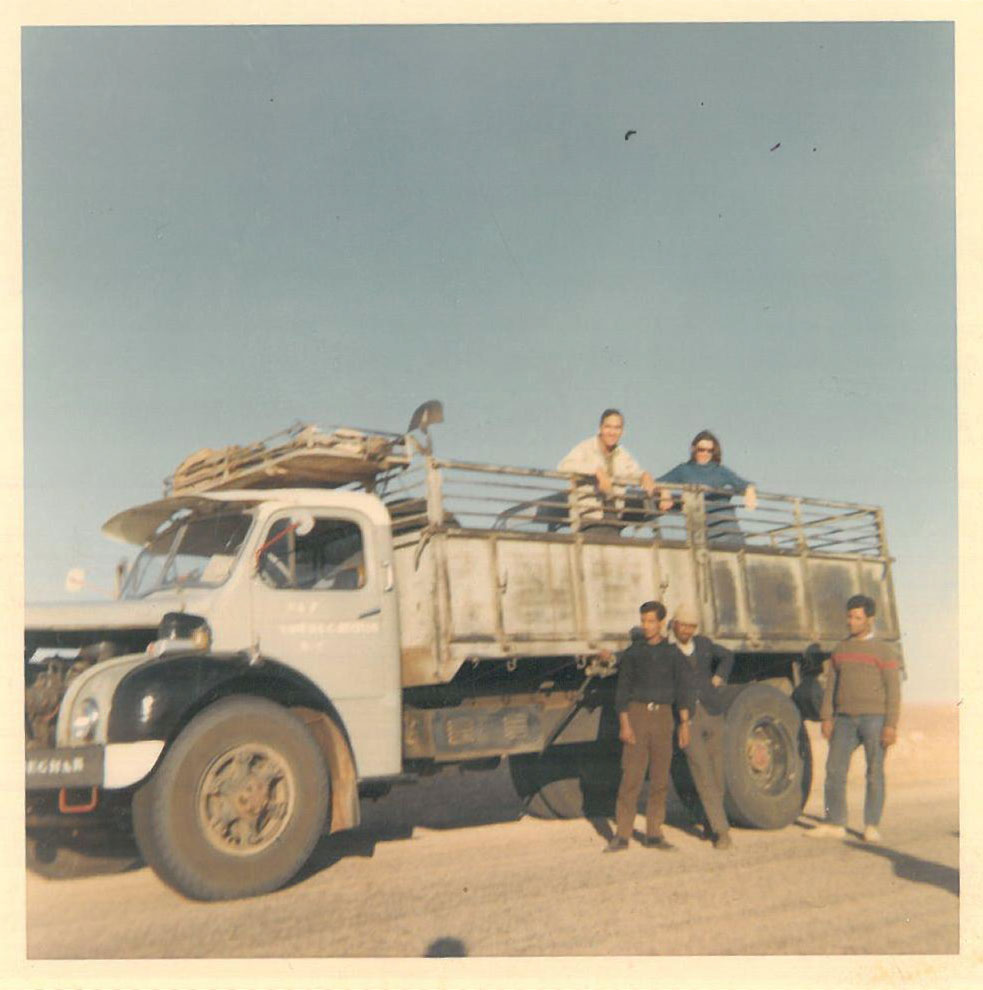

Photo Courtesy Ed Peck

In 1966, when I was principal officer at Consulate Oran, Algeria, we drove a small sedan to a tiny, isolated Saharan oasis to attend its annual, unusual festival: 300 miles south to Colum Bechar, now known as Bechar, where civilization ended; 210 miles east on a one-lane road to the town of Adrar; then 120 miles north through the sand to Timimoun.

Where there was no road, as experienced Sahara travelers who had served in Morocco and Tunisia, we just followed the tracks, reasonably confident they were made by those who went where we wanted to go. (Today there is a road and an airport.)

At one point, coming over a dune, I saw a man on a donkey in the valley. Driving over, but not too close, I greeted him properly and, for certainty’s sake, asked him to indicate the direction to Timimoun. He saw my surprise and consternation when he pointed off to the side of the tracks and said, “Timimoun exactly that way.” I apologized, and then asked if that was the way by car. He looked at me with what was clearly pity, and said, “No, you asked where it was, not how to get there. By car, follow the tracks.” Arabic can be quite useful.

We followed the tracks until an unseen rock cracked the oil pan about 35 miles from our destination, leaving us in absolute silence amid an endless sea of dunes. We had plenty of food and water, but luckily a jeep-load of Algerian soldiers appeared the next morning and towed us to Timimoun.

There I learned that the car would probably have to be sold for parts, the nearest mechanics and materials being in far-off Bechar, with no way to get it there.

On the second morning of the festival, however, a trans-Saharan truck brought a load of bagged and U.S.-flagged USAID wheat straight from Bechar. The villagers persuaded the drivers to take the American consul’s broken car on the return trip, in exchange for the American wheat, and a happy crowd watched and shouted encouragement as villagers struggled to put it on that big truck—by hand.

We traveled the long, bumpy trip back to Bechar inside the car on the truck.

We traveled the long, bumpy trip back to Bechar inside the car and took a train to Oran. The Army later delivered the car to us there, where it was repaired and used for the remainder of the tour.

That included: the outbreak of the 1967 Arab-Israeli War; broken diplomatic, but not consular relations; nine different mob demonstrations outside the offices-residence; evacuation of all the other Americans; temporarily running our nation’s only one-man post; and flying the only in-country American flag, without further assaults, until full relations were restored several years later.

The most compelling memory of Algeria, however, is not of the mobs, but of the enthusiastic crowd that watched the raising of the car, cheering loudly and repetitively in Arabic and French, thanking America, still waving until lost to view. That experience still generates a pervasive feeling of personal pride and patriotism.

I coincidentally rediscovered this photograph of the trip, not seen for decades. I am no longer sure of the exact circumstances in which it was taken, but if you look closely you can see the car’s roof behind us.

Read More...

- A Traveler In The Foreign Service: A Conversation With Ambassador Ed Peck (Gadling, Oct. 8, 2012)

- Speaking Out: Recognizing Those Who Made a Difference (FSJ, Sept. 2010 article by Edward Peck)

- Doing the Wrong Thing for the Right Reason (Edward Peck for American Diplomacy, “Life in the Foreign Service” Series)

- Edward L. Peck, Principal Officer, Oran (1966-1969) (ADST Interview, starts on page 69)