Up Close with American Exhibit Guides to the Soviet Union, 1959-1991

The USIA exhibit guides were young and enthusiastic, and they spoke Russian. Here’s what it was like to be on the front lines of the Cold War.

1959 American National Exhibition Moscow • 1961 Plastics USA Kiev, Moscow, Tbilisi • 1961 Transportation USA Volgograd, Kharkov • 1962 Medicine USA Moscow, Kiev, Leningrad • 1963 Technical Books USA Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev • 1963-64 Graphic Arts USA Alma-Ata, Moscow, Yerevan, Leningrad • 1964-65 Communications USA Leningrad, Kiev, Moscow • 1965 Architecture USA Leningrad, Minsk, Moscow • 1966 Hand Tools USA Kharkov, Rostov-na-Donu, Yerevan • 1967 Industrial Design USA Moscow, Kiev, Leningrad • 1969-70 Education USA Leningrad, Kiev, Moscow, Baku, Tashkent, Novosibirsk • 1972 Research and Development USA Tbilisi, Moscow, Volgograd, Kazan, Donetsk, Leningrad • 1973-74 Outdoor Recreation USA Moscow, Ufa, Irkutsk, Yerevan, Kishinev, Odessa • 1975-76 Technology for the American Home Tashkent, Baku, Moscow, Zaporozhye, Leningrad, Minsk • 1976-77 Photography USA Kiev, Alma-Ata, Tbilisi, Ufa, Novosibirsk, Moscow • 1976 USA 200 Years Moscow • 1978-79 Agriculture USA Kiev, Tselinograd, Dushanbe, Kishinev, Moscow, Rostov-na-Donu • 1987-89 Information USA Moscow, Kiev, Rostov-na-Donu, Tbilisi, Tashkent, Irkustsk, Magnitogorsk, Leningrad, Minsk • 1989-91 Design USA Donetsk, Kishinev, Dushanbe, Alma-Ata, Novosibirsk, Volgograd, Baku, Vladivostok, Khabarovsk

Lucidity Information Design, LLC; data from State.gov archive

Photography USA exhibit guides in Tbilisi, Georgia, in 1977. See if you can find the future diplomats in this photo, among them Mike Hurley, Philippe DuChateau, Howard Clark, Dolly Harrod (Commerce), John Aldriedge, and Tom Robertson.

Courtesy of Mike Hurley

American traveling exhibits in the USSR between 1959 and 1991 were the centerpiece of the U.S.-Soviet Cultural Exchange Agreement signed in 1958. Renewed annually, the agreement served as the basis for joint programming until formally abrogated by the Kremlin after the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The “American Exhibitions to the USSR” program began with the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959, the setting of the famous “kitchen debate” between Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, and ended with Design USA in 1991. The exhibitions—meant to introduce America to Soviet citizens and to dispel misinformation about the U.S.—showcased American ingenuity in 87 separate showings of 19 exhibitions across 12 time zones of the Soviet Union. (See map above.)

On display across the exhibits were examples of American ingenuity, technology, and daily life—from graphic arts, photography, and agriculture to outdoor recreation, technology for the home, and medicine. The exhibits reached scientists, educators, government leaders, industrial managers, intellectuals, artists, and the average worker in some 25 different cities—from the cosmopolitan centers of Moscow, Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), and Kiev (now Kyiv) to the far reaches of Tashkent, Novosibirsk, and Vladivostok.

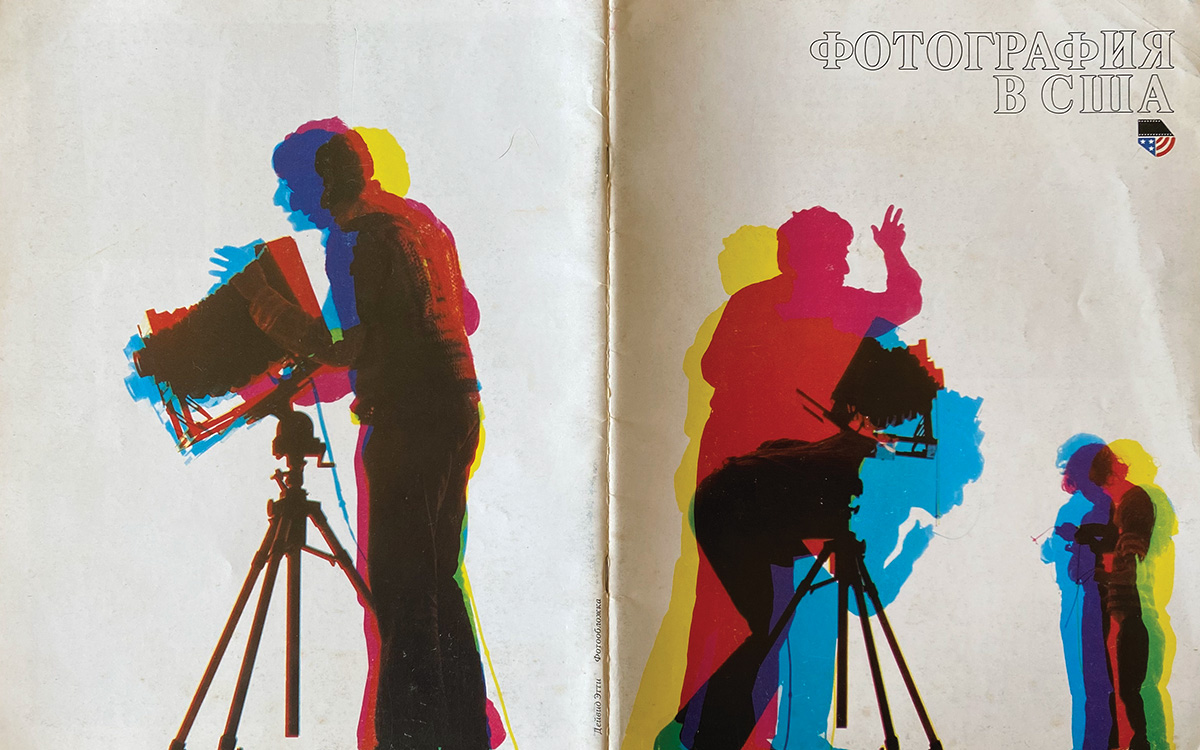

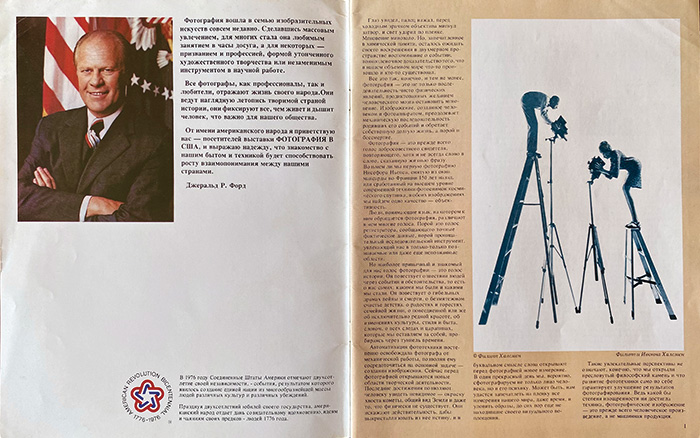

The Photography USA brochure, at 64 pages, was given to each visitor as they left the exhibit, along with a pin called a znachok.

Courtesy of John Beyrle

The brochure always featured a greeting from the current U.S. president inside the front cover.

Courtesy of John Beyrle

Some 20 million Soviet citizens saw the exhibitions and enjoyed the opportunity to speak openly with the young Russian-speaking American guides, who candidly discussed the basic values and beliefs of American society. Approximately 300 Americans worked as guides in this historic outreach effort. Many went on to careers in diplomacy, business, law, academia, and the arts where their language skills and overseas experience were a plus.

The primary outreach to the people of the Soviet Union, the exhibitions dramatically illustrated how cultural exchange can be the starting point for increased understanding and more constructive relationships between citizens of the world. The program, which also included less well-known Soviet exhibits to the U.S., required the participation of people from all spheres of American life and was only possible through the close cooperation of the former United States Information Agency (USIA), the American private sector, and the intrepid guides who brought the exhibits to life.

The experience of being a guide, and being connected to the exhibits, was life-changing for all those who participated. In addition to becoming more fluent in Russian, they also came to understand the Soviet Union in a way few others could in those years. And like A-100 orientation classes who enter the Foreign Service together, many of the exhibit guide cohorts from different exhibits remained in touch, some for decades and until today.

The Agriculture USA exhibit brochure

Courtesy of John Beyrle

We want to thank all the former guides who shared their reflections with us: John Beyrle, Rose Gottemoeller, John Herbst, Mike Hurley, Laura Kennedy, Allan Mustard, Jane Picker, Tom Robertson, and Kathleen Rose. And special thanks to Ambassador John Beyrle for assisting with reaching out to this outstanding group and sharing his collection of exhibit pins.

In the following, the nine former exhibit guides mentioned above reflect on their experiences and the significance of the program. Seven of the nine went on to careers in the Foreign Service, and six became ambassadors.

The pieces appear in chronological order according to the exhibit dates. Each guide wrote in response to a set of prompts from the Journal:

- When were you an exhibit guide, and for which exhibit?

- What were your ingoing instructions? Was there a basic script for your engagements?

- How much of a priority was countering disinformation?

- How did audiences react? What kinds of questions did they ask?

- How did you establish credibility/rapport with your audiences?

- Please describe what was most memorable and striking about your experience.

- What were the expected/anticipated outcomes of this engagement? Any unexpected or unanticipated outcomes?

- What were your primary difficulties as a guide, and how did you overcome them?

- What insights and lessons can we take from the exhibits experience to address today’s influence challenges?

—Shawn Dorman, Editor in Chief

For a full exhibit chronology and interviews with former guides, see the 2009 collection put together by the State Department Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs for the 50th anniversary of the start of the program, archived at https://bit.ly/Exhibits-50th. Also see the excellent Fall 2016 Wilson Quarterly articles by Izabella Tabarovsky, including photos and interviews with guides from the Photography USA exhibit in Novosibirsk, found at https://bit.ly/WilsonExhibitsCollection.

We Never Felt Like Strangers

Jane M. Picker

Medicine USA / Moscow and Kiev / 1962

★★★★★

Politically it was a period of great tension between our two governments: Gary Powers and his U-2 spy plane had been shot down two years earlier over Russia (and he did not use the poison pill that he had been told to take if captured). It was during our exhibit that the United States ended its moratorium on nuclear weapons testing in the atmosphere. The crowds visiting Medicine USA the day after this announcement were unnaturally subdued but recovered within a day or two. The most popular song being sung throughout Russia while I was there was “Do the Russian People Want War?” The answer sung was nyet! Despite the strains, the U.S. Information Agency’s Medicine USA exhibit in 1962 was clearly a success in Moscow and Kiev (now Kyiv, the capital of independent Ukraine), at least from the perspective of the U.S. government.

We exhibit guides had a training session in Washington, D.C., in February before leaving for Moscow. However, as we later realized, we were much too excited to listen very carefully to whatever rules were being read to us. There was certainly no recollection of a basic script of which we were later reminded, including that we should never meet with a Russian citizen more than once. If this was a rule, it was never observed.

Each exhibit had a small pin (znachok) that was given out as a souvenir with the exhibit brochure as attendees left the exhibit. Pictured here are the small pins (1” diameter), along the outer ring. Each exhibit also had a big pin (bolshoi znachok, or “BZ”) worn by each guide as a badge. The two BZs in the middle are from the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow and 1989-1991 Design USA. These were sought after as prize souvenirs. Soviets had a long tradition of trading pins (znachki).

Courtesy of John Beyrle

As guides we each had very different jobs: Those who were medical doctors were expected to be talking with Russian doctors, while some of us were more likely to be speaking to members of the general public. My job was to demonstrate a mock-up of an American drugstore. Members of the audience would ask me questions and would often joke. For example, a question about the use of rubbing alcohol elicited laughter with the comment, “We would drink it!” A very large mock-up of a toothbrush elicited the question of whether it was meant for the use of elephants. Personal questions were common: Why was I not married? And how large, in square meters please, was the apartment that I lived in back home, and why would I be living in it alone?

There were never any questions raised challenging our credibility. Except for a few professional agitators in the audience (who were overwhelmingly told to be quiet by the rest of the audience), everyone wanted to listen to us and ask questions. The most striking and unexpected aspect of the experience was the joviality of the crowds, and the requests of those of our own age asking to meet with us after the exhibit closed (which was usually at 7 p.m.), which we all did. Striking, too, was the warm welcome that we always received everywhere from those of our own age. Unwelcome experiences involved being followed in the streets by KGB agents and their attempts to prevent Russian citizens from befriending us. But even strangers would try to help us, like taxi drivers quietly trying to lose KGB cars (easily recognized by their make and radio antenna) that would try to follow us.

The conclusion I drew from my experience was simply that we and the Russians with whom we met never felt like strangers. We were always completely comfortable with one another. A renowned Russian law professor years later contrasted this with his experience with the British lawyers with whom he had interacted for 20 years. When I asked him why he thought he was more comfortable with Americans, he said that we were very much alike in our personalities. As evidence, he said that we would laugh at the same jokes. He did not find this surprising, he said, since it was basically Yiddish humor.

I have returned to Russia many times since 1962, most recently in 2019. Although I have traveled to and lived in a number of countries outside the United States, I feel most at home in Russia. No two peoples in the world are more alike than Russians and Americans.

The conclusion that I draw now from my months with Medicine USA and subsequent visits to Russia is this: We should continue to try to maintain our friendships with old friends still in Russia as well as those who have now left the country. And within the United States we should fight as hard as we can against the culture wars that so many in the U.S. are now trying to promote.

Who Had It Better?

Tom Robertson

Technology for the American Home / Zaporozhye, Leningrad, Minsk / 1975-1976

★★★★★

After serving in 1975-1976 as an exhibit guide for Technology for the American Home, Tom Robertson was deputy director of the Photography USA exhibit in 1977. Here he is, during that latter assignment, mixing it up with Soviet visitors in Novosibirsk.

Paul Schoellhamer

I served as an exhibit guide with Technology for the American Home from September 1975 to March 1976. We were involved in building and taking down the exhibit in the Soviet cities of Zaporozhye, Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), and Minsk, as well as in working on the exhibit floor five to six hours a day explaining and answering questions about the exhibit and any and all questions about life in America.

We met in Washington beforehand for a three-week training period. This was to brief the guides, most of whom only had knowledge of the Russian language in common, about American housing and all of its elements. We had architects and builders brief us, and we had sessions on the Russian terms for housing. We also had experts brief us on various statistics about life in America (e.g., average salaries for Americans; costs of items, including higher education and health care; unemployment benefits). We were given printed materials with this information included, as well as long vocabulary lists.

Early on we were assigned two different stands each on the exhibit floor. For each stand, there was a script in Russian that we were encouraged to memorize. In fact, after working a couple of weeks on any stand it would get tiring answering the same questions over and over, so usually we would exchange stands with other guides every few weeks. Each of the stands had panels with average prices for the various items on display, so that Soviet visitors could see what these would cost the American consumer. We had three kitchens (a country kitchen, a modern kitchen, and the kitchen of the future). For almost all urban Soviets, housing had improved immensely after World War II, with plumbing and electricity; but it still consisted of modest apartments, and the idea of having your own house in the suburbs with an expansive kitchen was simply incredible.

There were no scripts on combating disinformation, just facts and your own personal experience. I recall that my friend and eventual roommate (John Herbst, a future U.S. ambassador to Uzbekistan and Ukraine) and I did an Econ 101 tutorial for the other guides, a simple macroeconomic briefing on inflation, GDP, unemployment, and how the U.S. economy worked because most in the group had no background in economics.

Not surprisingly, most of the questions visitors asked weren’t directly related to the exhibit but were more generally about life in America. Most Soviets knew from their press about unemployment and the fact that many in the U.S. had limited access to health care, and that college education was “horribly expensive.” But they had no context and, of course, were missing critical facts. So we tried to provide that context and those facts.

It was not uncommon for a matronly visitor to listen to our stories and then walk away with the comment, “U nas luchshe [We’ve got it better]!”

I think we gained the most credibility by telling our own stories. We told visitors how much each of us was being paid (much more than the average Soviet!), how unemployment benefits and health insurance worked, and how we had paid, if at all, for our college education. These were often complicated stories: You’d tell them about the different costs between private and state universities, for example, and then you’d tell them how you (and your parents) paid for it—in my case a combination of scholarships, loans, and jobs. It was a long explanation, but crowds of as many as 50 persons would stand there fascinated by the discussion. Then, if they were really interested, they could go to a different guide and hear their story and compare.

And the guides’ approaches were often very different. For instance, we would be asked about the war in Vietnam. One guide might say he opposed the war completely and had demonstrated against it in the States; another would say he supported the war as a battle against communism. Soviets had a hard time believing that an American hired by the U.S. government could flatly state that he opposed the war and had fought against it.

Tom Robertson suited up to help out on Photography USA, while serving as deputy director for the exhibit.

Robert Fenton Houser

I recall that not long after we arrived in Zaporozhye in September 1975, there was an accident at the city hall where scaffolding had come tumbling down, and a couple of people had been killed. We only knew about this because our Russian friends and contacts told us. The next day in the paper there was no mention of the accident, but there was mention of a train accident somewhere in the United States where 8 people had been injured (but no one was killed). When Soviet visitors would argue that the Soviet media always told the truth, and never shied away from covering a story, that was the case I would mention. People, and not only in Zaporozhye, would nod their heads knowingly and move on.

Over the years I worked with exhibits (1975-1981), my reading of Soviet newspapers and periodicals led me to the conclusion that Soviet propaganda got more sophisticated in reporting on the trials and tribulations of life in America. In 1975 the tale was pretty simple: unemployed Americans with no income, sick Americans with no health care, high school students unable to go to wildly expensive colleges and universities. Over time the stories had to get more sophisticated; they had to mention unemployment benefits, health insurance and free health care, scholarships and loans for poorer students.

Ironically, although the wealth of American society came through, to many Soviets, American life seemed too insecure and too complicated. It was not uncommon for a matronly visitor to listen to our stories and then walk away with the comment, “U nas luchshe [We’ve got it better]!”

What was most memorable about the experience was that so many Soviets saw the exhibits as a meaningful moment in their lives, much as I am sure Americans did in the late 19th century when the circus came to town. It was a part of your life you would never forget. In many cities visitors would come to the exhibits with the brochure and exhibit lapel pin they had gotten years earlier at a previous exhibit. We guides joked among ourselves about being “rock stars,” because on the exhibit stand we would command audiences of enormous size. In addition, it afforded us direct access to everyday Russians and their thinking, something I could not get enough of later in postings as a diplomat to Moscow.

A Firsthand Look at “Agitprop”

John Herbst

Technology for the American Home / Zaporozhye, Leningrad, Minsk / 1975-1976

★★★★★

The November 7 Revolution Day parade in Alma-Ata, 1976.

Robert Fenton Houser

Working as a guide was the second of three steps I took toward becoming a Foreign Service officer focusing on the Soviet Union. This career idea first occurred to me in high school when I read George Kennan’s 1958 book The Decision to Intervene. The first step was to attend Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service and take the intensive Russian course in the language school. Studying there for three years and one summer at Leningrad State University gave me a great grounding in Russian.

My planned second step was to get a master’s degree in international affairs. But while a college senior, I read a flyer that offered the opportunity to “travel around the Soviet Union and to be paid money for the privilege”—an advertisement to work on the U.S. Information Agency’s Technology for the American Home exhibit. I put off my plans to attend the Fletcher School, took a job as a legal assistant in New York City, and applied to work at the exhibit. I reported to USIA in Washington, D.C., in August 1975.

That was perhaps the most important decision I ever made. It not only facilitated a career in diplomacy, but it introduced me to my future wife, Nadya Christoff, who was also hired to work the exhibit.

Seven months as an exhibit guide in the Soviet Union turned my solid grounding in Russian into fluency. We spent five hours a day, six days a week for over a month talking to Soviet citizens in each of the three cities where we opened the exhibit.

But experience as an exhibit guide was far more than an excellent language lesson. It also provided a fascinating window into Soviet society. The exhibit comprised rooms in a typical American house. Guides would stand in the rooms to talk about both that room and any other subject the visitors chose to raise. Often these questions would focus on life in the United States, but at times it would also include political issues. This provided all exhibit guides a firsthand look at Soviet “agitprop” (agitation and propaganda). This was the elaborate Soviet program to sell their ideals, policies, and goals at home and abroad.

Naturally that also included undermining the adversaries of the Soviet Union and the messages stemming from those adversaries (the U.S. was adversary number one). While most visitors to an exhibit were simply interested Soviet citizens—and their thirst for unvarnished information about the U.S. was attested by the long lines to get in—government agents were in the crowd to monitor the conversation and at times to ask questions meant to embarrass the U.S.

When guides proved persuasive passing information to the crowds, the Soviets were quick to act. On one occasion in Leningrad, my visitors called into question the veracity of American media. I responded that since their information came from state-controlled media, they were not in a position to make informed judgments. I asked if they knew that during Stalin’s time, the Soviet Union suffered from a cult of personality. When they responded affirmatively, I said that, of course, during the cult of personality, the Soviet media did not reveal it, but in fact contributed to it. They agreed. What, I asked, had changed in their media to prevent dissemination of bad information today? This prompted a protest from the Soviet side of the exhibit that I was spreading anti-Soviet propaganda.

My future wife, Nadya, provoked more rigorous countermeasures from government agents. She was one of two native speakers of Russian in our group, and she had a background that contradicted Soviet narratives about the dismal lot of poor people in the United States. Her grandparents had fled Bolshevik Russia, and her parents moved to the U.S. shortly after World War II. Her father died when she was young; and she, her mother, and two siblings lived in straitened circumstances. But, as she explained to the crowd, she went to college on a full scholarship. In Minsk, our minders decided that they could distract her by approaching in groups and shouting hostile questions. When we noticed this, we began to pay attention to her stand, and guides who were not on duty would come to help her when she was besieged with questions.

Working the exhibit only increased my interest in the U.S. Foreign Service. I started grad school the year I came back from the Soviet Union, took the Foreign Service exam my second year at Fletcher, and joined the Foreign Service 18 months later. At that time, the Foreign Service did not encourage new officers to take their first assignment in a familiar location. So my first assignment was to Saudi Arabia, followed by a stint on the Israeli desk. I made it to the Soviet Union on assignment three, working in Embassy Moscow’s political section. Things worked out.

Getting to Know the Real USSR

Rose Gottemoeller

Photography USA / Kiev, Alma-Ata / 1976

★★★★★

A typical crowd at the Photography USA exhibit. Inside the dome in Novosibirsk, June 1977.

Courtesy of John Beyrle

I was a U.S. Information Agency guide on the Photography USA exhibit from June to December 1976. The first city we opened in was Kiev (now Kyiv, capital of independent Ukraine). I was terrified. Although I had studied Russian at Georgetown University and could handle dialogue in the classroom, I had rarely encountered native Russian speakers “in the wild.” I didn’t know how well I would perform speaking with hundreds of them every day, in the exhibit hall and on the streets.

However, as anyone knows who studies a foreign language, the best way to get good at it is to speak with hundreds of native speakers every day, or to get a lover. I never got a lover—we weren’t supposed to go that far in our cultural exchange—but I did speak Russian for hours every day at the exhibit and far into the evening. During that period, young people were very curious about our small band of Americans, and they wanted to meet with us after hours, to walk in the park, to sit by the river drinking beer, to take us to one of the few nightspots then operating in Kiev. Some of them even cooked me dinner—I remember one young man who had remarkable eyes, one blue and one green. He cooked me a pan of fried potatoes served up with shots of vodka. It took me a while to realize that meal was probably all he had.

Kiev was also the city where I first realized that Ukrainians are distinct from Russians, with their own nationality. In the 1970s, the solidity of the Soviet empire was not much questioned in the West. We tended to use the homogenized term “Soviets” to describe the citizens of the USSR. I give the USIA and the U.S. government credit that they did not accept that idea and always tried to send along at least one guide who spoke the language of the Soviet republic where we were stationed. In Kiev, her name was Elie Skoczylas, and she was a wonderful personality, lively and confident, not at all afraid to take on all comers.

I didn’t understand Ukrainian, but I loved to watch Elie on the exhibit floor. She gave as good as she got and evidently was plenty entertaining, because before too long she had huge crowds of up to 100 people gathered around her. By contrast, I don’t think that I, speaking Russian, ever gathered more than 30. Waves of laughter would rise around Elie as she evidently commented on everything, told jokes and stories, and pushed back against security service provocateurs who tried to heckle her.

Pretty soon, travelers were coming from western Ukraine, from Lviv and the regions around it, to visit the exhibit and talk with Elie. On one memorable, hot Sunday (no air conditioning in those days), the line stretched for a mile outside the exhibit hall and many of them were coming to hear Elie. At that point, I understood fully that Ukrainians are not Russians, a fact that they registered clearly in their vote for independence from the USSR some 15 years later.

I had rarely encountered native Russian speakers “in the wild.” I didn’t know how well I would perform speaking with hundreds of them every day.

On Dec. 1, 1991, 90 percent of Ukrainians voted in favor of independence with 84 percent of the electorate participating. The results made sense to me after my exhibit experience in 1976. Wherever Elie Skoczylas is, I am grateful to her for bringing it home to me so early.

It was in our second city, Alma-Ata (now Almaty), that I realized the Soviet Union was more fragile than I thought. By the time we arrived there, winter was soon to be setting in, and a very cold and snowy winter it was. It didn’t help that the exhibit was set up in an ice rink. Of course, the ice had been melted and water drained away, but the heating system was weak, and the concrete floor might as well have been ice. The sensation I remember most from our time there was unrelenting cold.

I did enjoy the beauty all around us, though. We arrived in October at the height of the apple harvest, when the foothills of the Tien Shan Mountains were golden and full of apple orchards. Alma-Ata means “father of apples,” and the origin of the species, the first apple trees, are supposed to have come from the region. The markets were stuffed with the most delicious bright red apples. What none of us realized was that with no cold storage, within a week or two, they had disappeared from sale. No more apples. We always could find kimchi, however, what the locals called Koreiskiy salat—Korean salad. It turns out Koreans had come to Kazakhstan to work in the timber industry, so there was quite a large population of them in Alma-Ata.

We set up the exhibit in a snowstorm and opened in early November, just in time for the Nov. 7 Revolution Day celebration. Of course, we got the day off and were offered the chance to sit in a grandstand with local dignitaries to watch the parade. It was cold and snowing hard, so I opted instead to roam along the parade route, knowing that I could escape inside if it got too unbearable.

At some point, I was standing on top of a snowbank watching the parade go by when a group of World War II veterans holding signs of Politburo members hove into sight. When they got to my snowbank, one of them, holding a portrait of Leonid Brezhnev, signaled to the others. “Khvatit uzhe [Enough already],” he said, and shoved Leonid headfirst into the snowbank. The others followed suit with their placards, and then they clambered over the snow and headed off into the storm. I can’t swear that they pulled out a bottle of vodka on their way, but I wouldn’t be surprised.

That is the day I realized that the Soviet Union was not so sturdy and homogenous as I had been led to believe during my studies back in the United States. When Kazakhstan exploded in student riots in December 1986, among the first as the USSR began to melt down, I was not surprised. I remembered that snowbank 10 years earlier and heard in my mind the old man say, “Khvatit uzhe.”

Agitators Abound

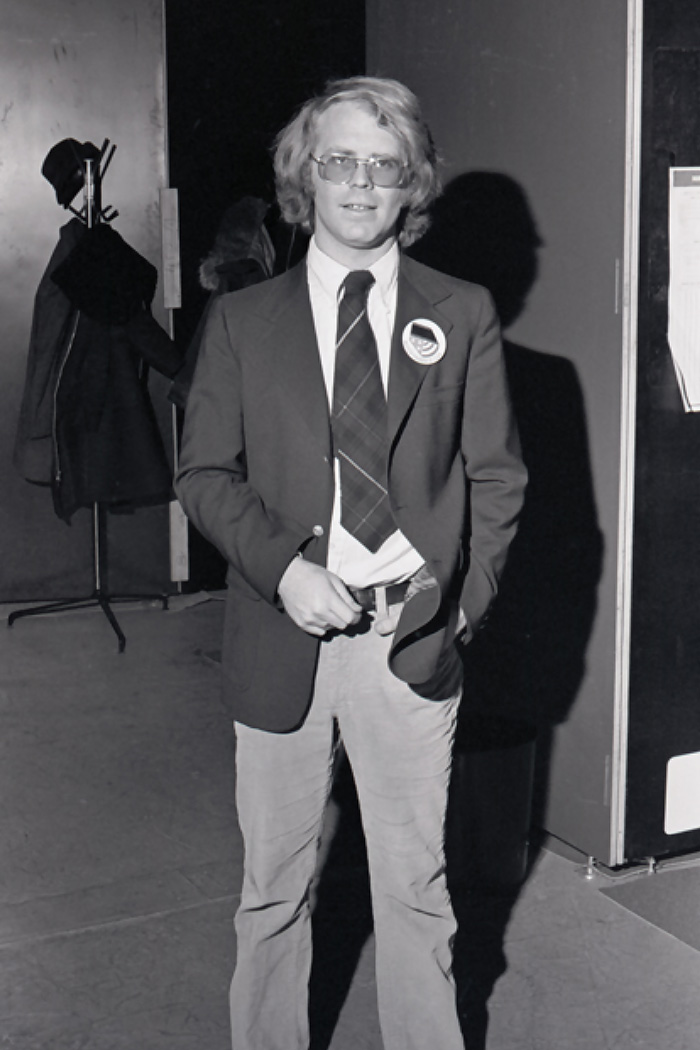

Mike Hurley

Outdoor Recreation USA, Photography USA, USA 200 Years / Yerevan, Kishinev, Odessa, Tbilisi, Ufa, Novosibirsk, Moscow / 1973-1977

★★★★★

Exhibit guide Mike Hurley on the fishing stand at the Outdoor Recreation exhibit in Yerevan (now the capital of independent Armenia), 1973.

Courtesy of Mike Hurley

My first visit to the Soviet Union was in 1972 as a college student participating in the summer Council on International Education Exchange (CIEE) program to study Russian language in Leningrad. Language immersion in Leningrad paved the way for my guide experience with USIA’s exhibits program (1973-1977). I experienced three different exhibits as a guide: Outdoor Recreation USA in Yerevan, Kishinev (now Chisinau), and Odessa; Photography USA in Tbilisi, Ufa, Novosibirsk, and Moscow; and USA 200 Years in Moscow.

The training in Washington prior to an exhibit was primarily about the technical side of the theme: photography, outdoor recreation, and a thorough grounding in the U.S. Constitution for USA 200 Years. It included pointers on how to engage Soviet audiences (e.g., don’t provoke with questions about Soviet atrocities), but I don’t believe there was ever a “script” or rules that restricted our ability to speak our own minds. This lack of rigid instructions surely was one of the important aspects of our ability to make points with the Soviet audiences. We actually believed what we were saying.

We were often confronted with agitators whose job it was to ask us pointed questions. The exhibits were visited by 10,000 people per day. As a non-native speaker, I found this emotionally and physically draining, so the added provocation compounded the encounter. Taking a “warts and all” position, however, was part of the strength of our presentations. I did not disagree directly with an interlocutor, but rather tried to explain the context of their questions.

They’d ask things like, “Why do you hate Black people?” “Why do Americans eat out of garbage cans?” “Why are you oppressing people around the world?” I found this early training to be of great use in my subsequent 30-year Foreign Service career.

Although we did not think of ourselves as overtly political, the Soviet security apparatus surely did.

An early formative experience was arguing with ideologues in the Soviet Union, people who say they believe something because their ideology explains reality in ways they might not have experienced. In Leningrad I asked one of my Russian teachers how she could be an atheist if she could not obtain a Bible. What came back were various quotes from Lenin. At one of the exhibits, a Soviet argued thus: “Of course North Korea is democratic—just look at the full name of the country, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.” Recalling early encounters like these helps me understand U.S. politics today, where people with different political points of view often find opposing views anathema.

A decade later, as a U.S. Embassy Moscow employee from 1987 to 1990, I saw a completely different aspect of misinformation on the exhibit floor. I visited a few of the exhibits in cities I had scouted for the program. There were far fewer unpleasant agitators; and, in fact, the issue was almost completely reversed. The same number of curious visitors came through the exhibits, but they would often ask leading questions that had to be dealt with differently. Someone would ask, e.g., “Isn’t is true that anyone in the U.S. can buy 25 pairs of jeans (a much sought-after commodity in the Soviet Union) at any time?” Well, yes, but few people would find that practical. The questioner was trying to impress upon his fellow visitors that the U.S. is a country of great abundance. Once again, it was important to give some context so our visitors would have a realistic idea about the U.S.

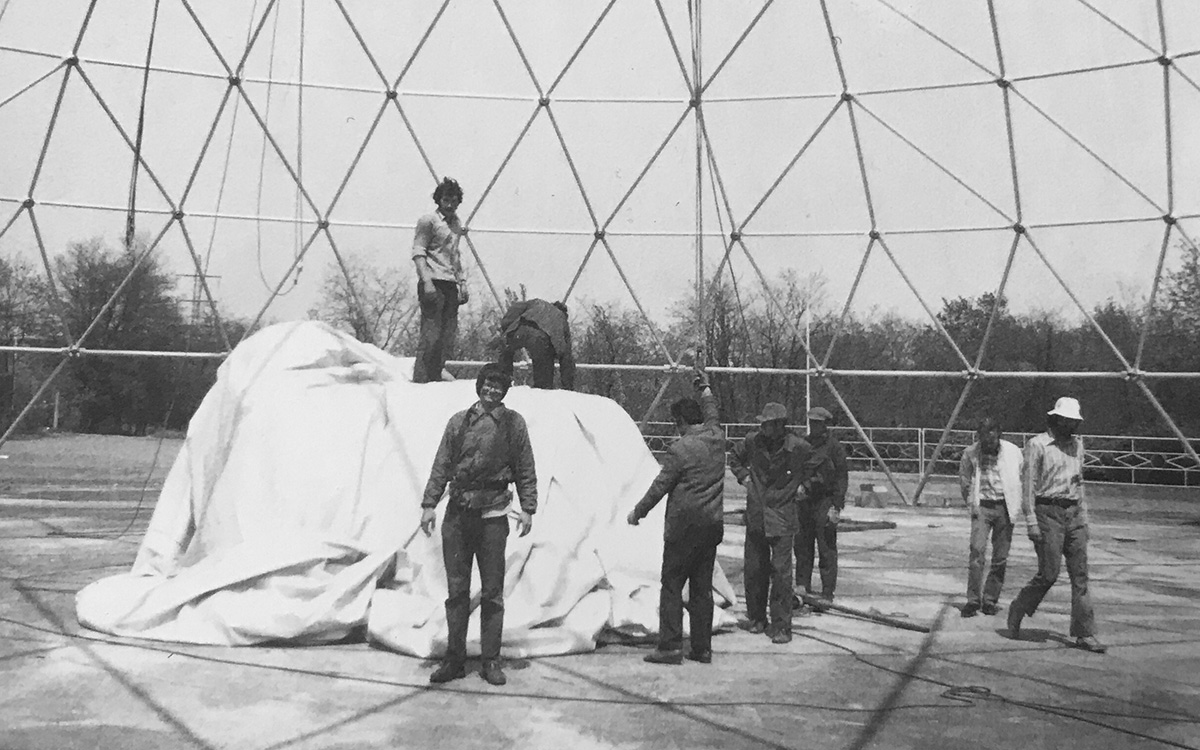

Mike Hurley, other exhibit guides, and local engineers building the geodesic dome in Odessa (now part of independent Ukraine) for the Outdoor Recreation exhibit, 1974.

Courtesy of Mike Hurley

Courtesy of Mike Hurley

Although we did not think of ourselves as overtly political, the Soviet security apparatus surely did. There were numerous articles in the media warning local citizens that the guides were somehow dangerous and up to no good. They were especially hard on our local guides in non-Russian areas such as Georgia and Moldova. We were sometimes followed by druzhiniki, watchers who threatened some kind of retribution against families of individuals we were trying to date. Dating usually consisted of walking along the river, as there was very little else to do.

That we were able to see things with our own eyes as guides was crucial to debunking myths about Soviets and, later, about Russians. I learned early that there was never going to be “a level playing field”—that is, if we played nice with the Russians, they would respond in kind—and that it was naive to think so. Russians are wonderful people and have a rich culture and abundant resources, but subsequent work in the region solidified my early impressions that they seem to need an “other.”

Someone asked me recently if I thought that things are worse now in Russia than in Soviet times, and whether we might do any of the old exchanges or cultural programs to ease tensions. On the whole, it’s worse now in Russia, but not quite Stalinesque (people do seem to fall out of windows, but wholesale murder of political dissidents is not the norm). At least in Soviet times starting in the 1950s, the Soviets saw a purpose in displaying their advances in science and culture. We were the enemy, but there seemed to be some sense to engaging us, perhaps handing us the rope to hang ourselves. That doesn’t exist today.

Today we’re still the enemy, but the sense of engaging us to score their own points is gone. Today, with President Vladimir Putin, there is a former KGB officer, a silovik (a member of one of the various security services), converted to a Russian imperialist in charge in what he sees as a winner-take-all existential struggle. The U.S. government should not stop trying to engage the Russians through our cultural and exchange programs, but with Russia passing laws to label all organizations that administer such programs foreign agents, I’m not holding my breath.

Excellent Exposure

Kathleen Rose

Photography USA / Ufa, Novosibirsk, Moscow / 1977

★★★★★

A Polaroid print of exhibit guides Kathleen Rose and John Beyrle taken by a fellow guide on the floor at Photography USA in Novosibirsk, 1977.

Courtesy of Kathleen Rose

Kathleen Rose talking with Photography USA exhibit visitors.

Paul Schoellhamer

I was a guide on the second half of Photography USA in 1977. At that time there was a bit of a lull in the Cold War, known as détente in the West and razryadka in the Soviet Union. There had been successful SALT talks, a joint U.S./USSR space mission, and a number of cultural initiatives. That is not to say there were not still significant disagreements over conflicts around the world, but there was some relaxation of tensions between the late sixties and 1977, and that is how it felt to me on the exhibit. There were still visitors who wanted to spar with us on what was wrong with America, but it was always possible to defuse the situation and to get the crowd on your side.

The first city we opened in was Ufa, the capital of Bashkortostan in the Ural Mountains. Ufa was close to a thousand miles east of Moscow, but it seemed like it was on another planet. I had been a student in Moscow and Leningrad in 1972 but had never been to a provincial Soviet city that saw few, if any, tourists. Ufa had hosted a U.S. Information Agency exhibit five years earlier, but other than that it had seen few foreigners. I remember that the hotel we stayed in still had the smell of recent varnish with a top note of insecticide. They had clearly gone to some trouble to make things presentable for the visiting exhibit.

There is an apocryphal quote attributed to Andy Warhol that says something to the effect that everyone should have the experience of being famous for 15 minutes. That is a little of what it was like to be an American guide in a city where few people had any expectation of coming face to face with someone from the United States. I found the crowds to be mostly friendly, hungry for information, and fascinated with the exotic American guide creatures in their midst.

I was asked by visitors if the guides were picked for their intact white teeth. People were surprised that we had gotten to our mid- to late-20s and beyond without acquiring any metal teeth. Another day I was asked if American women could have babies in five months. The questioner probably figured that Americans were so efficient at everything else that we must have been able to streamline childbirth, as well.

In all three cities we worked, the people I interacted with were dubious about the American “melting pot” and very interested in guide ethnicity. I would tell them I was 100 percent American, but that did not satisfy them. They would persist, “But what is your origin?” When I told one Russian visitor that my father was Greek, he replied, “Yes, I saw a hint of the East [namyok vostoka] in your face.” He promptly followed that up with “I want to talk to a real American!” and headed over to the guide next to me who was a WASP poster child.

It was pretty ironic that my candor turned out to be some powerful propaganda.

During our training in Washington, D.C., we were given a lot of exposure (pardon the pun) to photography of all kinds and were provided with an extensive vocabulary list of photographic terms. At the same time, we were told that Soviet visitors would be most interested in talking about social, cultural, and political issues.

I found that while many of the questions we got were not about photography, there was actually a great deal of interest in detailed information about it. I thought that I was prepared to talk about amateur photography because I had spent a lot of time taking photographs with an SLR and printing my own photos in a darkroom. But I wasn’t prepared for many of the questions, including questions about the formula for the developer D76. It turned out that not only did Soviet amateur photographers not have access to a store that could print their photos, they had to mix their own darkroom chemicals.

In Novosibirsk, I was asked to explain in detail the 12-step process by which an image becomes a print in a Polaroid camera. At every photo stand I worked on, there was a hunger for that kind of detailed information. At one point I asked a visitor why he was asking so many technical questions. He said that it was his impression that in America we all swam in this vast sea of available information and wide-ranging opinions, and that we took it all for granted. In the USSR, he explained, information was rare and precious, and he was always hungry for more.

Kathleen Rose (center) on the Polaroid stand with future FSO Kaara Ettesvold (to Rose’s right, engaging with visitors) in Novosibirsk, 1977.

Paul Schoellhamer

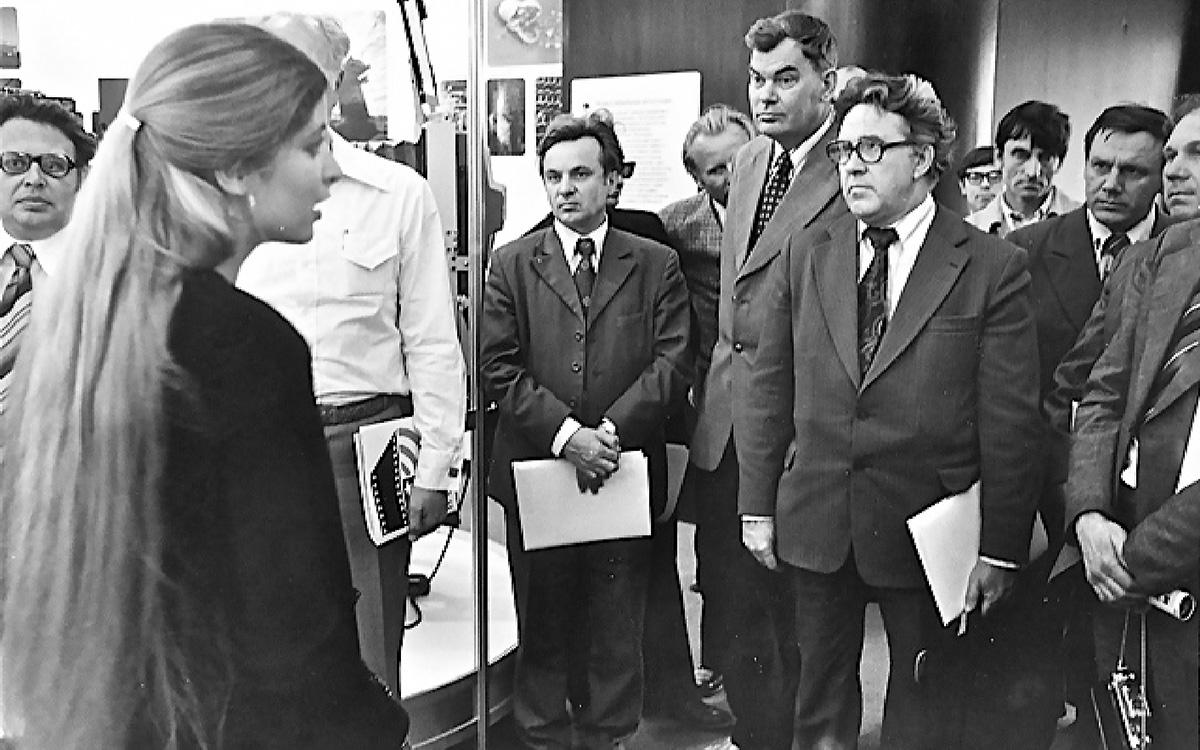

Kathleen Rose talking with Soviet press and officials at the exhibit opening for Photography USA.

Paul Schoellhamer

Every USIA exhibit was a spectacular and compelling display that got across the message that America was a pretty amazing place. I certainly didn’t dispute that, but I decided early on that I also wanted to be honest and engage with visitors on some of the more difficult aspects of living in a relatively free and open society. I talked about race issues. I talked about gun violence. I talked about some of the disadvantages of an agricultural system that did a phenomenal job of trucking produce vast distances, but bred tomatoes and other fruits and vegetables that were sturdier than they were tasty.

I often had repeat visitors. One time a young man who had come to my stand on a number of occasions called out from the back of the crowd: “Every day you criticize your country, and the next day you are still here. We are so impressed!” I had gone out of my way to be honest and truthful about the pros and cons of life in America and to not just spout propaganda. It was pretty ironic that my candor turned out to be some powerful propaganda, at least to that young man.

Over the decades, the USIA exhibits were a feast for the senses and a source of valuable information. Wonderful as the exhibits were, there was no doubt that the Russian-speaking American guides were a major draw and were very effective at building bonds with the millions of Soviet citizens who came to the exhibits. In my view, these interactions were not only transformative for the visitors but for the American guides, as well. Back then Americans didn’t have a lot of opportunities to meet citizens of the USSR face to face. It was certainly a powerful and moving experience for me to get to make real connections with the exhibit visitors, and those memories have stayed with me for more than 50 years.

I worked as a guide in the time before the World Wide Web, when information (and disinformation) was not as accessible as it is now. Even though it is a very different world today, I believe that the power of those face-to-face connections has not diminished. It may no longer be practical to resurrect traveling exhibits, but I do hope that in the future there will be more opportunities for cultural exchanges between the people of our two countries, as challenging as that appears to be now.

Tapping an Intense Interest in America

Allan Mustard

Agriculture USA / Kishinev, Moscow, Rostov-na-Donu / 1978-1979

★★★★★

Three Agriculture USA exhibit guides in Rostov-na-Donu in 1979. From left: Allan Mustard, Mark Bloom, and Richard Vogen.

Courtesy of John Beyrle

From October 1978 to June 1979, I was an exhibit guide for Agriculture USA. The exhibit director was Tom Craig, deputy director was Tom Robertson, John R. Beyrle was general services officer, and information officer was Jocelyn Greene. I was on the second half, which visited Kishinev (now Chisinau, capital of independent Moldova), Moscow, and Rostov-na-Donu. My assignments were the milking parlor stand, with a horrible dummy cow covered in flower-patterned fabric, and as an interpreter in the library. The only script we had was a canned speech we had to memorize related to our specific stand on the exhibit, which we used for opening day ceremonies when dignitaries walked through.

Our instructions going in were to be ourselves, and to express our opinions freely. We had a two-week crash course in agriculture organized by the University of Illinois, which for the guides with no farm or ag background proved very useful. I was mostly familiar with dairying, so learning about Midwest agriculture—corn and soybeans—was useful. After that training, we were pretty much on our own, but we always had Tom Robertson, John Beyrle, and Jocelyn Greene, who were experienced former guides, to go to for advice.

Maybe a maximum of 10 percent of the questions were rooted in disinformation. Some of them came from professional agitators we assumed were employees of the KGB. Audiences asked all kinds of questions: How much does food cost in America? How much do you earn? Do you have brothers and sisters? What do your parents do for a living? What kind of music is popular in America? Very basic stuff.

Because it was an agricultural exhibit—and many Russians in the 1970s had private plots, and if they were not themselves involved in production knew somebody who was—we got lots of questions about agriculture. A couple that stick in my memory were about herd yields, the average volume of milk produced per cow in the United States, and whiskey. When I told Soviets that the U.S. herd average was 5 metric tons of milk per cow per year, they accused me of lying. I would then reply that the United States had only the second-highest average herd yield in the world, that Japan was number one, which was true. Soviet herd yields were less than half that.

In Kishinev, a rather ragged fellow dressed in a typical cotton batting coat asked me: “Just what is American whiskey?” The crowd laughed and hooted at him, but he turned to face them and said, “I rode a bus from Odessa all night to come here to ask this question, and now this young man will answer me.”

He was very dignified in his ragged clothing. I did my best to describe corn sour mash Bourbon whiskey to him. If questions got too technical for a guide, the guide could give the visitor a library pass—in each city we had three specialists, usually university professors from the United States, who could answer technical questions.

Our instructions going in were to be ourselves, and to express our opinions freely.

We kept a weird question list. One of the women guides was asked where she got her teeth. I was once asked why I speak Russian “almost well” (I started studying Russian too late in life to be a native speaker, so have an accent and make stylistic errors).

We established rapport with our audiences by conceding that America is not number one in every category. They were shocked that we would admit that. Japan had higher herd yields in dairying. Other countries had higher yields in crops. You could always find categories where we could point out that we’re good, but some other countries are better. That stunned visitors.

The first days were rough, but in time we got better at knowing what statistics we needed to memorize to get our points across—Soviets loved numbers. I had an easier time establishing credibility than most other guides because I had grown up on a dairy farm and had been in 4-H, so I actually knew a fair amount about dairying and could talk knowledgeably about it. One agitator put his foot in his mouth when he loudly declared to the crowd, “He doesn’t know anything about agriculture,” then ended up being laughed at by the audience when I showed that I did. That said, you couldn’t reach everybody, and some people went away having swallowed Soviet propaganda whole.

The deeply intense interest in America on the part of Soviets was the most striking aspect of my experience. Most of them knew they were not getting the whole story or the real story from Soviet state-controlled media, but they didn’t know what the story was. The exhibit was an extremely rare opportunity to converse with a real, live American who spoke Russian, even if KGB minders were observing the entire time. The Soviet information space was dominated by state-generated propaganda, not unlike Putin’s Russia today, with real information coming mostly from shortwave radio broadcasts by VOA, Radio Liberty, Deutsche Welle, and BBC World Service, which were jammed. So the curiosity was intense.

We were there to give our version of what America is. You knew you had won an argument when the Soviet interlocutor said, “U nas luchshe [We have it better here]!” That was grasping for the last straw.

In really heated moments, if a visitor was being nasty or obnoxious, I might ask, “Where do people immigrate? How many immigrants come to the Soviet Union, and how many to the USA?” That was a hard question for the agitators to deal with, because everybody knew that Soviet Jews were immigrating by the hundreds at that point, some to Israel, but many to the United States, and virtually nobody in those days immigrated to the USSR.

In one case, a visitor asked if I could read Russian, not only speak it. I assured him I could read Russian. He asked what Russian authors I liked to read, and I replied, “Nobel Prize laureates.” He smiled, “Ahh, Sholokhov!” to which I replied, “Also Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn.” Even though Dr. Zhivago and The Gulag Archipelago had been banned, everybody had at least heard of them if not had a chance to read a samizdat (clandestine) copy of them, and the crowd around me burst out laughing.

The Soviet army belt traded for a U.S. flag patch to Allan Mustard in Kishinev (today’s Chisinau, Moldova). He wears the belt today as a Cold War trophy. Inset: the large bolshoi znachok guide badge from Agriculture USA.

Allan Mustard; Inset: John Beyrle

In general, people were simply curious, and most were friendly. There were, of course, hard-core communists who were anti-American, but you simply had to take them in stride. At one point I was arguing with a fellow who claimed the USSR was much freer than the United States, so I asked him how many communist parties the Soviet Union had. “One, of course,” he answered. “We have it better,” I said. “We have three: the CPUSA headed by Gus Hall, the Revolutionary Communist Party headed by Bob Avakian, and the Socialist-Workers Party.” That dumbfounded Soviets, that we could have three communist parties, and that they were allowed to stand for election.

On impulse, before leaving the United States, I bought a bunch of American flag patches. I stitched one on my denim baseball cap and carried a few in my shirt pocket. Periodically someone would come up and ask how to get one of those patches, and I would say that I had a few to swap for souvenirs. One fellow swapped me a flag patch for his Soviet army belt, not just the buckle, but also the leather belt he had worn as a soldier. Another swapped a collection of matchboxes commemorating Soviet farm tractors and implements, and one fellow swapped me a catalog from a farm machinery exposition.

Every exhibit visitor received a button and an exhibit brochure. A lot of visitors loved anything related to America, which to them was a mysterious country that evoked enormous curiosity and, to a certain degree, envy.

Many years later, in the 2000s, while in Rostov-na-Donu on embassy business, I met the executive of an agribusiness firm who remembered me from the exhibit in that city. He was a little boy in the 1970s, and he distinctly remembered the tall guide in a jean jacket and denim cap with an American flag patch on it talking about dairying. So we left some impressions.

As for unanticipated outcomes, I didn’t expect to be recruited into the Foreign Service, but in Moscow one evening at the embassy’s Marine Corps bar, one of the agricultural attachés, Jim Brow, suggested that I join the Foreign Agricultural Service. He said, “You know agriculture and speak good Russian; you should come work for us. You just need a master’s degree in agricultural economics.” I got my M.S. in 1982 and started work at FAS in April of that year.

As far as lessons for today are concerned, we should bring exhibits back. President Carter canceled the exhibits after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the program was only restarted late in the Reagan administration for two more exhibitions. Then the program died, and USIA was absorbed into State Department, which was a mistake. We closed the regional programs office in Vienna that served our posts in the Soviet bloc.

USIA needs to be reestablished, exhibits need to be restarted, and Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty need a big boost in both funding and staffing. These programs were hugely successful in countering Soviet propaganda. We know how to do it, but we’ve unilaterally disarmed ourselves in the information war. When the war in Ukraine finally ends, we also need a massive exchange program, ranging from summer work/travel to high school and college academic exchanges, not just Fulbrights for post-docs.

Russians believe what they see with their own eyes, just like everybody else. But because not everybody can visit America or the West, we need exhibits and VOA to reach out to the rest of Russia.

Developing a Cadre of Russia and Other Area Specialists

Laura Kennedy

Agriculture USA / Kiev, Tselinograd, and Dushanbe / 1978

★★★★★

Laura Kennedy demonstrating a seeder to opening day crowds for Agriculture USA in Dushanbe, September 1978. The crowds were scant at first, because many citizens were still doing enforced cotton picking during the all-important harvest.

Courtesy of Laura Kennedy

My 1978 participation as a guide on the Agriculture USA exhibit was a small link in the 50 years of official U.S.-Soviet exchange exhibits. U.S. exhibits garnered huge crowds and even greater word of mouth over the half century of the program, made famous by the Nixon-Khrushchev “kitchen debate” engineered by William Safire at the 1959 inaugural exhibit. I had thousands of conversations with Soviet citizens over the course of six months in the cities of Kiev (now Kyiv, capital of independent Ukraine), Tselinograd (now Astana, capital of independent Kazakhstan), and Dushanbe (now capital of independent Tajikistan). These were multiplied thousands of times more by my fellow guides over the decades in one of the most successful U.S. government public outreach programs conducted in one of the modern era’s most rigidly controlled countries.

This type of face-to-face public diplomacy may seem obsolete in today’s digital world, but it had extraordinary reach behind that old iron curtain. Because of the Soviet state’s monopoly of information means and its citizens’ skepticism about the veracity of often false official reporting, conversations with these exotic emissaries from the outside world were eagerly traded and amplified privately by Soviet citizens.

When I returned years later to the newly independent states in Central Asia, I met countless citizens (including some who became senior officials in these former Soviet republics) who remembered the exhibits and had saved the little pins we gave out there. We may not have changed minds, but we certainly gave these Soviet citizens a direct sense of the freedom, individuality, and dynamism of American society. Most effectively, the American guides represented a range of backgrounds, spoke without a script, and certainly exploited their license to speak freely and critically of their own government.

This lack of an official line and the guides’ candor made a distinct impression on our audiences, who were eager to hear our views on all manner of topics, including opinions on the USSR. Of course, many Soviet citizens were hoping to hear validation of their own lives. While I may have been critical of Soviet government policies, I always sought to speak honestly about American shortcomings and find something positive to say about the (often dreary) lives of our citizen hosts (e.g., the richness of host nation culture, the generous hospitality shown us by host nation citizens).

The dome that housed Photography USA also housed Agriculture USA in 1978 in Tselinograd. A small provincial town then, today it is Astana, the ultramodern capital of Kazakhstan. The small red, white, and blue structures are grain silos in which agricultural equipment and information were displayed.

John Beyrle

Agriculture USA exhibit guide work crew in Tselinograd in June 1978. Exhibit guides physically put up and took down the exhibits, which surprised many Soviet visitors. From left: Robin Seaman, Larry Sherwin, R.D. Zimmerman, Laura Kennedy, Lance Murty.

Courtesy of Laura Kennedy

All of us citizen diplomats found our own ways to build rapport with our interlocutors and disarm hostile exchanges. The most effective means of deflecting the officially directed “provocateurs” was by developing a rapport with your audience so that they would turn on the attackers and tell them to “let the young person talk” and “show some hospitality to our guests.” In fact, despite the fact that the Cold War was a hard reality, there was a basic reservoir of popular Soviet interest in their American guests that surely frustrated Soviet propaganda officials. I encountered very little animosity among nonofficial Soviets toward Americans; sadly, that is no longer the case in today’s Russia.

In one notable case I remember, the medium was easily as powerful as the message. Our sole Ukrainian-speaking guide in Kiev, as we called it then, made such a powerful impression that Ukrainians flocked from hundreds of miles away to hear him speak their native tongue (the other guides all spoke Russian). The crowds were so intense that visitors daily implored this guide, Walter Lupan, to climb on top of our showpiece Ford pickup truck so that more could hear him. This was an early lesson to me of both Ukrainian nationalism and the intense Soviet neuralgia to it—the guide was declared persona non grata by Moscow.

For someone like me, who later developed a specialty in arms control and nonproliferation, the exhibit also provided early lessons on how the Soviet government sought to instill its views on nuclear weapons in the popular sphere. Soviet “agitprop” (agitation and propaganda) seized on the “neutron bomb” (an enhanced radiation weapon reported to be under consideration by the U.S. for deployment in Europe), which I (and probably 99.99 percent of American or Soviet citizens) had never heard of before. The Soviet leadership began attacking it as a “capitalist weapon” (because it would rely more on lethal radiation and less on blast, which would theoretically minimize property damage).

This heretofore obscure type of weapon was injected into the questions posed to us by Soviet visitors, although we knew that what they were really interested in were the perennial questions such as what did such and such cost in the U.S., and nyet neytronnoi bombe (no to the neutron bomb) became a familiar phrase that still rolls around my head 40 years later! This manufactured outrage (the Soviets themselves were developing these bombs) presaged the massive propaganda campaigns the USSR mounted in Europe in the early 1980s in an attempt to block U.S. intermediate range nuclear deployments.

The nuclear issue leads me to one huge benefit of the exhibits program—the fact that it helped develop a talented cadre of Russian-speaking specialists in Russia and other areas of the former Soviet Union who gained direct experience on both official and popular attitudes and how one could most productively engage or counter disinformation. Former guide Rose Gottemoeller, negotiator of the New START treaty and NATO Deputy Secretary General, springs immediately to mind.

Guides later rose to prominence in a wide array of specializations, ranging from literature professor and international gastronomy expert Darra Goldstein to CNN Moscow Bureau Chief Jill Dougherty, to U.S. Ambassador to Russia John Beyrle, and a number of other ambassadors and U.S. government officials. My own early guide experience in Central Asia led me toward a career-long interest in Central Asia (office director, deputy assistant secretary, and ambassador). Countless numbers of experts in the field emerged from the exhibit guide ranks.

A number of us have long discussed the value of a conference that would bring together generations of guides to explore further lessons learned. Although this has never materialized, a number of books have examined the history of the exhibits, the Carnegie Institution held a conference in Moscow in 2007, and Ambassador (ret.) Ian Kelly undertook an interview project of former guides in 2008. Such a conference still ought to be held; but in the meantime, thanks to the FSJ for this look at a major U.S. success story in public diplomacy.

Diplomatic Training on the Exhibit Floor

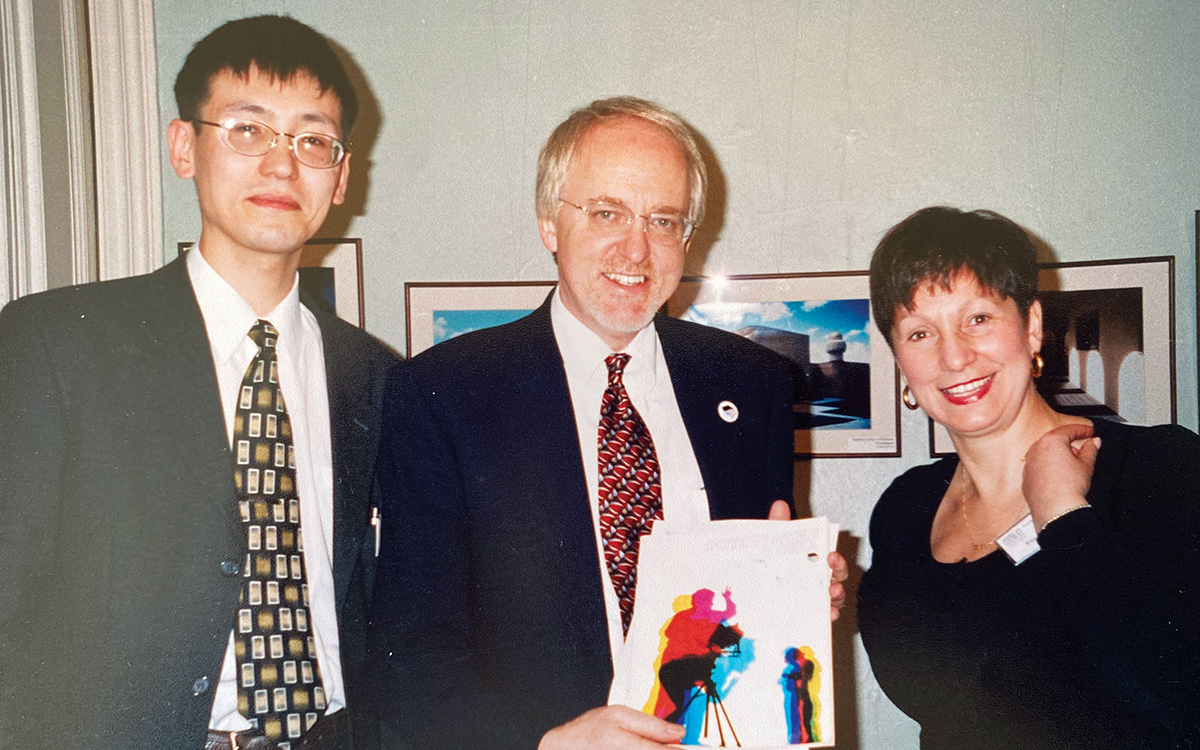

John Beyrle

Photography USA / Ufa, Novosibirsk, Moscow / 1977

★★★★★

Exhibit guides John Beyrle and Kathleen Rose on the stand at Photography USA in Novosibirsk, 1977. “The awestruck kid looking at the Polaroid photo Beyrle had just taken really conveys the fascination that so many had,” says Kathleen Rose.

Paul Schoellhamer

I served as a guide on the Photography USA exhibit in 1977, when I was 23. For Americans studying Russian language, literature, or history during the Cold War, working on an exhibit in the Soviet Union for six months—and getting paid for it, even at the GS equivalent of minimum wage—was the dream job everyone wanted. For many of us, it opened the door to a career in the U.S. Foreign Service that we might otherwise have missed. For all of us, it was singular experience of an intellectual and emotional intensity that we can still feel vividly, even 50 or 60 years later.

The whole point of the exhibits program was to offer a counternarrative to Soviet propaganda and disinformation about “the West” in general, and the U.S. in particular, through direct personal interaction with ordinary people in the USSR. Everything, from the name and design of each exhibition down to the glossy brochure given out at the exit, was designed to encourage visitors to question the Soviet view of the world, or to reinforce the doubts about the storyline that we knew many of them already had. But the 25-30 guides—the centerpiece of each exhibit—were not trained polemicists. We were young adults in our mid-20s, many fresh out of college, of varied backgrounds, and with unpredictable political views. How could the U.S. Information Agency be sure that we would be persuasive in “telling America’s story,” as a USIA motto put it? And to what extent should our interactions with Soviet visitors follow a script, even a rough one?

By 1977, when I joined the program, USIA had been designing and sending exhibits to the USSR for nearly 20 years. My exhibit, Photography USA, was the 15th in that series. Recent archival research has uncovered files showing that in the early years of the program during the 1960s, there was internal debate among USIA, the State Department, and other agencies regarding how much latitude the guides should be given to criticize U.S. policy or events—in particular, the Vietnam War and, later, the Watergate scandal. Over time, the experience gained with each new exhibit made it obvious that giving Soviet visitors a chance to see true “free speech” in action was much more valuable than trying to “script” the guides, which would have been difficult to accomplish in any case.

After our group assembled in Washington, D.C., in the spring of 1977, we began an intensive month of training designed by USIA to prepare us for what lay ahead. We were given material in Russian to help us describe in detail the photographic equipment or processes we were demonstrating, but the scripts we studied were technical in nature, never political. We also spent time studying lists of typical questions that visitors would be asking, so that we could personalize our responses in describing our educational and family backgrounds, the size and layout of our houses, what we paid for basic goods and services, and many other aspects of daily life back home.

This proved an absolutely essential part of our training because, though many visitors wanted to know the concrete details of how people did photography in America, they were overwhelmingly interested in asking about us. For the vast majority of Soviet citizens, who often stood in line for an hour or more to get into the exhibit, this was the first (and for most the only) chance they would have to speak to a real live breathing American who, as a bonus, spoke some approximation of Russian. We used to joke that USIA could design an exhibit called “Paper Clips USA”—and as long as there were Russian-speaking Americans staffing it, huge crowds were assured.

My experiences on the exhibit, although I didn’t realize it at the time, amounted to my earliest training as a diplomat. The keys to being effective as a guide on the stand or as an FSO making a demarche are basically two, I think. First, you must be a master of the subject matter: inside and out, backward and forward, until you can speak at length, in detail, and with self-confidence about any aspect of what is at issue. And second, you need to be able to understand the motivations of and demonstrate some empathy toward your interlocutor. As a guide, I found that a bit of humility and humor always helped “humanize” me in the eyes of the crowd (and there was almost always a big crowd, sometimes up to 30-40 people, surrounding us).

Although our pre-departure training in Washington was comprehensive, nothing could prepare us for the stark reality of the job, standing on the floor of the exhibit trying to engage intelligently with the ceaseless stream of visitors, up to 15,000 per day. In my early weeks out on the stand as a guide, it quickly became evident that I was seeing a vast cross-section of Soviet people. Many of the visitors were highly educated, but others clearly were not. Their outlooks ranged from sophisticated or even worldly to naive and crudely provincial. Most interestingly, on the political spectrum, I was engaging every day with both the truest of true believers in the Soviet system, as well as people who were essentially “closet dissidents.” These opposite types sometimes came into prickly contact with each other, right in front of us.

A typical crowd at the Photography USA exhibit, inside the dome in Novosibirsk, June 1977.

Courtesy of John Beyrle

One typical day I was out on the stand trying not to be drawn into an ugly argument with someone who kept loudly insisting on his ill-informed views about the many faults of U.S. society. He was, of course, only repeating (and embellishing on) the propaganda that everyone was being fed by the Soviet press; my job was to marshal some facts and figures and try to speak persuasively in Russian to rebut his claims. This was near the end of a two-hour stretch of similar encounters on the exhibit floor, and I was utterly exhausted mentally—like a boxer in the 12th round of a fight who could barely keep his arms up to prevent being clobbered. My loud friend started off on a new tack, going on about how America was an imperial, colonialist power.

Before I could even begin to refute this, a man standing next to him broke in and started haranguing him: “You know nothing about America! Historically, the United States has always been an anti-colonialist nation!” He went on, recounting our early history as a colony, the roots of the Revolutionary War, and later our support for decolonialization after World War II. After the loudmouth moved on, my defender smiled and winked at me in an avuncular way, as if to say, “Don’t worry about that idiot—you and I know the real score here.” I never saw him again and have no idea who he was. But it was an unforgettable moment, an early reminder that I was privileged to have a front-row view into a society that was much more complex, deep, and multilayered than most Americans—including, as it turned out, me—understood.

As U.S.-Russian relations worsened over the past decade, even before the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, I was sometimes asked if I thought the onset of a new “Cold War” meant we should start thinking about reviving the USIA exhibits program. I think the answer is clearly no. Those exhibits were a product of the unique times that gave birth to them—a highly effective means of giving millions of Soviet citizens a meaningful encounter with a world that was otherwise entirely inaccessible to them. Today, or for now at least, millions of Russians can and do travel freely in what was once “the outside world” on business, vacations, and family visits. Many millions more inside Russia can access streams of information from Russian media outlets that are not controlled by the state. There would thus be little value in sending teams of specialized Americans to Russia (even if we could) to try, at the retail level, to put a more human face on the United States. In a world of global connectivity unimaginable during the Cold War, there are far more sophisticated and effective ways to counter the Kremlin’s mendacious narrative and shine a spotlight on their aggression against Ukraine.

What we learned from the exhibits program, and what I think is still relevant to today’s Russia, is that people’s desire for the truth grows in direct proportion to the extent to which the truth is denied them. We need to offer our strongest support for the hundreds of thousands of Russians who now live in exile outside Russia—civil society activists and independent media journalists, scholars, and legal experts—who seek a different future for their country, and have both the skill and the will to ensure that the truth continues to reach the largest number of people inside Russia as possible.

As Embassy Moscow’s deputy chief of mission in 2004, John Beyrle visited Ufa and met two local residents who had attended the Photography USA exhibit there in 1977 and still had the brochure. They estimated close to 100 people had read it over the intervening 27 years; it was still in good shape but had been carefully re-stapled and taped at some point.

Courtesy of John Beyrle

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “U.S.—Soviet Cultural Exchanges” by Yale Richmond, The Foreign Service Journal, December 1988

- “Understanding Russian Foreign Policy Today” by Raymond Smith, The Foreign Service Journal, December 2016

- “The World Through Moscow’s Eyes: A Classic Russian Perspective” by Dmitri Trenin, The Foreign Service Journal, March 2020

- “Reflections on Russia, Ukraine, and the U.S. in the Post-Soviet World” by John F. Tefft, The Foreign Service Journal, March 2020

- 50th Anniversary of the American Exhibits to the U.S.S.R., U.S. Department of State Archives

- “A Tribe of Exhibit People: American Guides Recall Soviet Journey” by Izabella Tabarovsky, Wilson Quarterly, 2016