Reflections on Russia, Ukraine and the U.S. in the Post-Soviet World

The struggle between Russia and Ukraine, in which the United States has been involved for three decades, reflects the challenges of the continuing post-Soviet transformation.

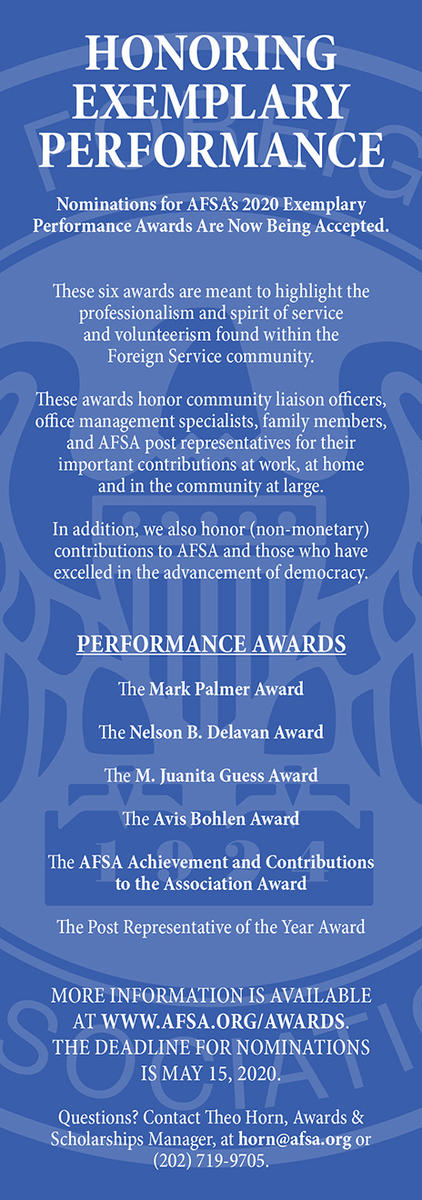

BY JOHN F. TEFFT

A close-up of Crimea, showing Ukraine and Russia.

Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty

The breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 was one of the great strategic inflection points of our time. It brought a formal end to the Soviet empire, but did not change the desire of Russian leaders to maintain a strong sphere of influence in the new independent nations on its periphery. In doing so, Russia confronted a resurgent national patriotism in some of those countries, along with a strong desire to integrate into Western political and security organizations.

Ukraine, along with Georgia, has been the primary battleground, literally and metaphorically, for this struggle. Ukraine shares a common historical heritage with Russia. Its leaders both competed and worked together with Russia for centuries. Both Russia and Ukraine initially managed the breakup of the Soviet Union and the reemergence of Ukraine as an independent country reasonably well, but tensions over what Russians call their “Near Abroad” were present from the start. Those tensions grew over time as Russia sought to reestablish its hegemonic control over an increasingly assertive and nationally conscious Ukraine.

This culminated in late February 2014, when Russian President Vladimir Putin decided to seize Crimea and foment a hybrid war in Ukraine’s eastern oblasts of Donetsk and Lugansk, the Donbas. The war has been fought by Russian and Russian-proxy forces with Moscow providing the direction, financing and weapons. These actions shredded the fabric of post-Soviet European security. Tragically, more than 13,000 people have died in the continuing fighting in the Donbas, and negotiations to find a solution have yet to achieve lasting results. Even if a resolution of the conflict is eventually reached, however, residual antipathy from this war will likely make it hard for Russia and Ukraine to find the compromises necessary to build a lasting peace.

In Putin’s view, things went from bad to worse when Yushchenko sought Ukrainian integration with Europe and NATO.

The United States has found itself in the middle of the struggle between Russia and Ukraine for more than three decades. Much of my Foreign Service career centered on this issue, as successive American administrations worked with the European Union and its member nations to help find a secure place in Europe for an independent Ukraine, while also trying to shape a cooperative relationship between Russia and Euro-Atlantic institutions such as NATO. To understand how we arrived at this point, we need to start in the days leading up to the end of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

On Sept. 4, 1991, not long after the failed August coup attempt against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, Secretary of State James Baker held a press conference at the State Department and outlined what would become U.S. policy goals as the Soviet Union collapsed and the new independent states came into being. Secretary Baker was about to leave for a Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe meeting in Moscow where he would meet with Gorbachev, Boris Yeltsin and other leaders. He then planned to visit the Baltic nations of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, which had already declared independence from the USSR.

Secretary Baker told the journalists gathered in the State Department Briefing Room that his discussions would be guided by five basic principles:

- self-determination consistent with democratic principles,

- recognition of existing borders,

- support for democracy and the rule of law,

- preservation of human rights and the rights of national minorities, and

- respect for international law and legal obligations, especially the provisions of the Helsinki Final Act and the Charter of Paris.

It was already apparent when he spoke that the centrifugal forces that would soon break up the USSR were well advanced. His goal at the press conference was quite clearly to lay out U.S. policy guidelines for the historic transition already underway.

This was particularly true in Ukraine. A strong, renewed spirit of national independence had been growing for some time. On Aug. 24, 1991, the Ukrainian Parliament, the Rada, led by Speaker Leonid Kravchuk, had voted to declare independence from the Soviet Union. On Dec. 1 a referendum was held, and 92 percent of the people of Ukraine voted in favor of approving the Rada’s Declaration of Independence. The turnout was 84 percent. Eighty percent of the inhabitants of the Donbas region voted for independence, and more than 54 percent chose independence in Crimea.

The next day, Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic President Boris Yeltsin recognized Ukraine as an independent state. Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev sent a telegram of congratulations to Kravchuk, expressing hope for close cooperation and understanding in “the formation of a union of sovereign states.” On Dec. 7-8, Kravchuk met with Russian President Yeltsin and Belarusian Supreme Soviet Chairman Stanislav Shushkevich at Belavezhskaya Puscha in Belarus and announced the end of the Soviet Union as a “subject of international law.” To replace it, they created the Commonwealth of Independent States. On Christmas Day 1991, the Soviet Union ceased to exist, and each of the former Soviet republics became truly independent.

The United States had initially been cautious in recognizing the impending collapse of the USSR. There were serious debates within the George H.W. Bush administration about how quickly to move, fed by a fear that the demise of the USSR could lead to the fragmentation of the region and a potentially chaotic situation with international implications. Command and control of the Soviet Union’s nuclear weapons was a major preoccupation of Washington. Secretary Baker famously said: “A Yugoslav-type situation with 30,000 nuclear weapons presents an incredible danger to the American people—and they know it and will hold us accountable if we don’t respond.”

President Bush himself had warned against “suicidal nationalism” in his famous Aug. 1, 1991, speech to the Ukrainian Rada in Kyiv. Bush had put his hope in Gorbachev to reform and hold the USSR together. The two leaders had worked closely together on German reunification and other issues high on the White House foreign policy agenda. The Rada speech backfired. It outraged Ukrainians and many Americans who felt it was in the United States’ clear interests to more forthrightly support an independent Ukraine. One critic, New York Times columnist William Safire, criticized Bush’s speech as a miscalculation and dubbed it the “Chicken Kiev speech.”

Protest against joining NATO, organized by Viktor Yanukovych's party, in Kyiv’s Maidan Square in 2005.

Arthur Bondar

Within a month, however, Gorbachev was severely weakened by a failed coup attempt, and the Ukrainian people had voted overwhelmingly in favor of independence. It now became clear at the White House and throughout the U.S. government that the USSR was coming to an end. Secretary Baker moved quickly to forge relationships with Russia, Ukraine and the other new states.

From the start, the United States pursued a two-pronged post- Soviet strategy: trying to build a good relationship with the new Russia, marked by cooperation and even partnership, but at the same time making a major effort to create productive bilateral relationships with the new independent states. This approach reflected U.S. strategic objectives as well as American values. In his 1997 book The Grand Chessboard, former National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski characterized Ukraine as a “geopolitical pivot because its very existence as an independent country [means] Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire.” Although not often publicly expressed by officials to avoid antagonizing Russia, this strategic recognition has undergirded much of U.S. policy to this day.

Geopolitical objectives were augmented by a desire in the Bush administration to help build democracies and market economies in the new states, as Secretary Baker had stated in his press conference. In the following months, he visited each new capital, meeting with each nation’s new leadership. Under his direction, the State Department moved quickly to create and staff new embassies in each capital, along with new consulates general in Vladivostok and Yekaterinburg in Russia.

It was a major achievement of the U.S. Foreign Service. The new embassies and consulates positioned the United States on the ground throughout the Eurasian landmass to promote American interests. In Kyiv, the United States had already established a consulate general in February 1991, but then upgraded it to an embassy on Jan. 23, 1992, when the U.S. and Ukraine established full diplomatic relations.

Efforts to manage this two-pronged policy in Eurasia have continued under every U.S. administration, Republican and Democratic, for the past three decades. Initially, the United States was able to balance the relationship reasonably well, but over time this balancing act became more difficult.

Despite the formal recognition of Ukrainian independence by Yeltsin, many in the Russian political elite, particularly in the security services and the military, never accommodated themselves to Ukraine’s independence. While the Yeltsin government officially signed onto the 1994 Charter of Paris for a New Europe, guaranteeing sovereignty for all states of the former Soviet Union, the so-called Russian power-ministries (supported by politicians like the late Moscow mayor, Yuri Luzhkov) continued to work in Crimea and other areas such as Transnistria, Abkhazia and South Ossetia in ways that undercut those principles.

I witnessed a very candid example of attitudes among the Russian elite at a farewell reception in June 1999, when I was completing my assignment as deputy chief of mission in Moscow and returning to Washington to prepare for a new assignment as ambassador to Lithuania. A senior Russian official with whom I had worked came up to me, toasted me with a shot of vodka and said: “Well, John, good luck in Lithuania. You know we always understood that the Baltic nations were different, unlike Ukraine and Georgia—which, of course, are part of Russia.”

Even most members of the Russian elite who recognized Ukraine’s independence saw Ukraine as an integral part of Russia’s history and wanted to keep it within Russia’s sphere of influence. They resented efforts by the United States and the European Union to offer Ukraine a place in a broader Europe.

At a national prayer event early in the morning in the center of Kyiv in late November 2013 during the “Euromaidan” revolution, Ukrainians protested the Yanukovych government’s decision to turn toward Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union instead of signing an association agreement with the European Union.

Arthur Bondar

A more assertive Russian policy toward Ukraine slowly emerged after Vladimir Putin succeeded Yeltsin as president. During the first decade of the 21st century, Russia’s economy had steadily improved due to massive profits from the extraction of oil and natural gas. Russian resentment against American policy and its desire to reassert itself on the world stage grew correspondingly. At the 2007 Munich Security Conference, Putin launched a broad-based diatribe against U.S. foreign policy, criticizing the United States for its development of ballistic missile defenses, its military actions in Iraq, NATO expansion and promoting democracy within Russia’s legitimate sphere of influence.

Putin’s desire to keep the United States and Europe out of the “Near Abroad” grew more pronounced. This approach had been strongly influenced by his negative reaction to the Western-supported Orange Revolution in Ukraine in late 2004. Putin was personally stung when Ukraine’s Supreme Court blocked the corrupt election of Putin’s favored candidate, Viktor Yanukovych, and ordered a new election that paved the way for Viktor Yushchenko to be elected president. This “colored revolution” came to be seen as a seminal event by many in the Russian elite. Reflecting their lack of understanding of real democracy, some believed that the CIA had organized it all. They feared that what had happened in Ukraine could happen in Russia. Putin opposed democracy in Ukraine, in part because he feared losing control of that nation, but also because he feared the impact of real democracy on his control of Russia itself.

In Putin’s view, things went from bad to worse when Yushchenko sought Ukrainian integration with Europe and NATO. Russia’s position hardened particularly over the prospect that Ukraine could become a member of NATO. In April 2008 at a summit in Bucharest, NATO leaders debated whether to grant Ukraine and Georgia a membership action plan (MAP), which would have potentially set them on the road to eventual membership in the organization. At the end of the summit, the leaders, many under heavy Russian pressure, could not reach consensus on this, simply stating instead that one day the two countries would become NATO members. Even that decision outraged Putin, who saw it as a challenge to Russia’s sphere of influence. Ironically, Russian leaders misread the decision: It actually meant, in effect, that even a MAP for Ukraine and Georgia was not going to be approved for many years.

At a dinner on the final day of the summit, Putin tried to explain Russian opposition to Ukraine’s membership in NATO to President George W. Bush. Not realizing that a microphone on the table had not been turned off, Putin was heard saying to Bush: “You don’t understand, George, that Ukraine is not even a state. What is Ukraine? Part of its territory is Eastern Europe, but the greater part is a gift from us.” Putin clearly was referring, first, to the western regions of Ukraine that at various points of history were controlled by Lithuania, Poland and Austria.

In the second part of that sentence he was referring to eastern and southern parts of Ukraine, which were colonized by Russia in the 17th and 18th centuries, and to the decision taken on Feb. 19, 1954, by the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet (when Nikita Khrushchev was general secretary of the Communist Party) to transfer the Crimean Oblast from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. In subsequent years, Putin’s rejection of a truly independent Ukraine has become more frequent, and he often asserts that Russia and Ukraine are one nation, one people with only cultural differences. This, of course, arouses the ire of Ukrainians.

Many in the Russian political elite had long chafed at NATO’s first two expansions to include nations of Central Europe and the Baltic region. Although Russia had agreed in 1997 to a joint cooperative program in the NATO-Russia Founding Act and to the 2002 reboot of the act that was designed to give new impetus to NATO-Russia relations, it never seriously invested much effort to build cooperative security through the act’s mechanisms, particularly after Putin came to power. With memories of Napoleon and Hitler ingrained in their collective psyche, and despite possessing the world’s largest nuclear arsenal, Russian leaders had not abandoned their historical anxiety about invasion of the homeland. They refused to accept the idea of a new security relationship with the West, even with post-Soviet reassurances by NATO of a desire for political and military cooperation.

Opposing NATO also played a major role in Russian domestic politics. Increasingly, the NATO bogeyman was used by Putin and others to play on Russian fears and thereby generate domestic support for the Putin administration. This became especially true after the 2008 world financial crisis brought the Russian 2000-2008 economic boom to an end, and the Kremlin could no longer justify the regime’s legitimacy on the basis of steadily rising living standards. The Russian elite reverted to defining Russian security in zero-sum terms, seeing the nations on the Russian periphery as secure buffers. They refused to see the potential benefits to Russia of having more secure and economically prosperous nations in Central and Eastern Europe. They did not want to recognize that NATO was fundamentally a defensive alliance and had sought to build cooperation with Moscow. They needed an enemy.

Russians and Ukrainians march for peace in Moscow, 2014.

Arthur Bondar

In late 2008 Russia invaded Georgia, following a long period of military provocations against the Caucasian state. The invasion of Ukraine came in 2014. Both military actions were designed to reassert Russia’s claims to regional hegemony and to keep NATO from making Ukraine and Georgia members of the Alliance. Putin justified Russian action on the grounds of protecting Russian-speaking residents wherever they might live.

Russia held a referendum in Crimea on March 16, 2014, and claimed that, with an 83.1 percent voter turnout, 96.77 percent voted for the integration of Crimea into the Russian Federation. Voters were not given the choice to remain an autonomous oblast within Ukraine under the current constitutional structure, an option that U.S. International Republican Institute polls in the years before the Russian invasion had consistently shown was favored by a plurality if not a majority of the Crimean population. In a May 2013 IRI poll, for example, 53 percent of Crimean residents interviewed responded to a question on the future status of Crimea by saying they wanted to remain autonomous in Ukraine; 23 percent wanted to be separated and given to Russia; and 12 percent wanted autonomy for Crimean Tatars in Ukraine.

Russian policy did not have to follow a confrontational path. Russian experts have articulated in private and in public an alternative approach that the Kremlin did not take. Dmitry Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, wrote in March 2018, for example, that Russian policy had not served Russian interests: “Since the start of the conflict in Donbas, the formation of the Ukrainian political nation has proceeded on a clear anti-Russian platform. It did not have to be, had Russia’s foreign policy been more enlightened. The emergence of independent Ukraine—as well as Belarus—is a natural process, something that Russia would be better off understanding and accepting as a fact.

“As independent nations,” Trenin continued, “Ukraine, overtly, and Belarus, less so, are tilting toward the European Union, for the same reasons as Romanians and Bulgarians. A clever Russian policy should have seen that and offered them a concept of how to ‘go West’ without breaking with Russia. This is too late for Ukraine but can still be done with Belarus.”

An armored vehicle troop carrier on the front line in Donbas, 2016.

Arthur Bondar

A Ukrainian soldier on guard duty.

Arthur Bondar

Ukrainian patriotism and a deepening national consciousness are no longer simply major issues emanating from the traditional hotbeds of Ukrainian nationalism in the western regions of the country. They now increasingly emanate from the entire nation, particularly from many among the younger generation who do not have the memories of the Soviet Union shared by their parents and grandparents.

At the same time, the number of Ukrainians supporting integration into Europe has grown. It is now easier to obtain a visa and travel to Europe, including visa-free trips to E.U. member countries for many categories of travelers. Other benefits of the association agreement signed by former President Petro Poroshenko in Brussels on June 27, 2014, are also being felt in Ukraine. This was a major goal of Ukraine during and after the Orange Revolution and remained so during much of the presidency of Viktor Yanukovych (February 2010-February 2014). During my tenure as ambassador to Ukraine, which coincided with

Yanukovych’s presidency, Ukraine and the E.U. had negotiated an association agreement and a comprehensive free trade agreement with support from the United States. Yanukovych’s sudden reversal in November 2013—when he decided not to sign the association agreement and instead seek membership in the Russian Eurasian Union in exchange for a $15 billion loan from Russia—had shocked the Ukrainian population. It led to the protests on the Maidan Square in Kyiv, followed by violent repression of the protest by the regime, Yanukovych’s flight to Russia and, subsequently, the Russian invasion of Crimea and military operation in the Donbas.

During my time in Kyiv, the Ukrainian people had increasingly seen ties to the European Union as not only realizing the European destiny of Ukraine, but as a means of introducing the rule of law inside Ukraine itself and eliminating unchecked corruption by Ukrainian and Russian oligarchs. For years Ukrainian governments had been pressured by Moscow to do its bidding, particularly in the energy sector. Ukraine has been a major transit country for sending Russian gas to Europe. Ukrainian businessmen made deals with Russian state firms, raking off profits as middlemen from the transshipment of energy across Ukraine.

Ironically, Russia’s proxy war in the Donbas and its approach to Ukraine over the last six years have themselves helped forge a much stronger and more widely shared sense of national identity, and contributed to even greater popular support for Ukraine’s independence and for greater integration with the West. Russian actions in Crimea and the Donbas in 2014 caused a sharp drop in the number of Ukrainians who had a positive attitude toward Russia. From more than 90 percent during the 2008-2010 period, it fell to as low as 24 percent in early 2014.

Attitudes seem to have improved somewhat this year, however. On Oct. 15, 2019, The Moscow Times reported the results of a joint study done by the independent Russian Levada Center and Ukraine’s Kiev International Institute of Sociology, which found that attitudes toward each other’s country seem to be improving after the election of President Volodymyr Zelensky in May 2019. According to the study, 56 percent of Russian respondents assessed their attitude to Ukraine as “good” or “very good.” A May 16, 2019, Ukrainian poll conducted by several Ukrainian survey and polling organizations showed that there is now a roughly 60-40 split between Ukrainians who have very or quite positive attitudes toward Russia and those who do not. According to this poll, however, Ukrainians still have a much more sharply negative attitude toward President Putin himself. Only 12.6 percent of those polled described their attitude toward Putin as positive, 65.6 percent as negative and 16.6 percent as neutral, with the rest undecided.

The results of a Pew Research Center Poll—“European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism,” published in October 2019—revealed that 79 percent of Ukrainians have a favorable view of the European Union, compared to 11 percent unfavorable and the rest undecided. Support for membership in NATO has grown substantially since my time in Kyiv. During my tenure, support for NATO membership remained relatively constant at around 23 to 24 percent. As my colleague and former U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Steven Pifer noted in a June 6, 2019, article for Brookings Institution, polls over the past four years have shown pluralities—in some cases, even a majority—in favor of joining the Alliance. For example, a January 2019 survey had 46 percent in favor as opposed to 32 percent against. Clearly the war in the Donbas has forced a substantial change in the attitudes of Ukrainians about the security of their country.

The Ukrainian Army 53rd Brigade in Donbas, February 2016.

Arthur Bondar

A wounded Ukrainian soldier.

Arthur Bondar

The United States–Ukrainian relationship has traversed a rocky road over the last three decades. Ambassador Pifer has written an excellent history of it, The Eagle and the Trident: U.S.-Ukrainian Relations in Turbulent Times (Brookings Institution Press, 2017). He chronicles how the United States was able to persuade Ukraine to transfer nuclear weapons from its territory to Russia for elimination, but had less success in persuading the Ukrainian leadership to adopt reforms necessary to become a successful modern European state. The U.S. and Ukraine have also had disagreements over sales of sophisticated weapons and technologies to regimes in Iran and Iraq, and human rights violations inside Ukraine.

Yet, despite our differences, the U.S. has consistently supported Ukraine’s sovereignty and independence from Russia, as well as Ukrainian territorial integrity. The Obama administration winced when President Yanukovych cut a deal with Putin in early 2010 extending the Russian lease on the Sevastopol naval base in Crimea. In 2014 the Obama administration responded to the Russian invasion of Crimea with a firm set of sanctions and, eventually, military training and some nonlethal military equipment for Ukrainian troops fighting in the Donbas. The Trump administration went further, providing Javelin anti-tank weapon systems and other defensive systems to aid Ukraine. Most analysts credit this support along with the bravery and increasing professionalism of Ukrainian soldiers for helping Ukraine stem the pro-Russian tide in the east.

The overwhelming election victory of President Zelensky underscored the desire of Ukrainians of all political stripes for an end to the war in the east, for real change in the country and for integration with the West. This includes many of the Russian-speaking Ukrainians living in eastern Ukraine outside Donetsk and Lugansk who voted for Zelensky, himself an easterner born in Kryvyi Rih. Most U.S. analysts believe his election represents a triumph for democracy and Ukraine’s vibrant civil society. They believe the United States should do all it can to encourage Zelensky to take the steps he promised—and which successive American administrations have sought—to build a more democratic, less corrupt and economically prosperous country.

Zelensky’s election may open up an opportunity for a settlement in the Donbas and for Russia to extract itself from the conflict—provided the Kremlin wants to get out. The Dec. 9, 2019, meeting in Paris between Presidents Putin and Zelensky held out the promise of a lasting cease-fire and a possible political settlement, but progress will depend on how the meeting is followed up. For much of the past six years, Moscow has viewed sustaining a simmering conflict in the Donbas as a useful means of keeping pressure on the government in Kyiv and distracting it from the internal reforms it needs to pursue. Zelensky will have to negotiate carefully with the Russians. Ukrainians favor a negotiated solution to the Donbas conflict, but they do not want to compromise Ukrainian sovereignty, and they have made clear they do not want new elections in the Donbas until Russian troops are out.

On the domestic front, the Ukrainian Rada has already adopted significant new reform legislation. This includes, for example, a law lifting immunity for members of the Rada, which was used for years by politicians and businessmen seeking to protect themselves from criminal charges for corruption. In addition, the new Ukrainian prosecutor general, Ruslan Ryaboshapka, is already hard at work taking on the entrenched corruption in the country. Ryaboshapka has a history of fighting corruption; he worked for Transparency International and, famously, resigned in protest in 2017 from the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption.

Ryaboshapka has taken exception to criticism, particularly in the United States, that Ukraine is still awash in corruption today. In a Nov. 27, 2019, interview with the Financial Times, the prosecutor general said he was “‘bothered’ by daily depictions of a lawless Ukraine in the U.S. impeachment inquiry. ‘This is not fair … Ukraine is not as corrupt as is being presented there. … We have made significant progress as of late.’” It is in the clear interests of Ukraine and the United States that Ryaboshapka succeed. In fact, nothing will probably have a greater long-term impact on the development of Ukraine and its relations with Russia than building a strong and less corrupt economy.

Although American policy toward Ukraine has remained consistent overall, there has been a constant drumbeat among critics who believe that the United States should be more realistic about Russia. Some American analysts argue that Washington should take the prospect of NATO membership off the table for Ukraine and Georgia, in exchange for a Russian withdrawal from the Donbas. Others recommend that Ukraine concede sovereignty of Crimea to Russia in exchange for financial and other considerations for Ukraine.

Critics of these approaches argue that they would, in effect, recognize Russia’s claim to a privileged sphere of influence in neighboring states. They argue that there is no guarantee that Russian behavior will change, and that Russia could very well continue to pursue its aggressive attempts to dominate the region. Others argue that the people of Ukraine (along with Georgia and other Central and Eastern European nations) will simply not accept Russian domination. They do not want to cede territory to Russia, or return to being a country without the independence and freedoms they have come to expect.

Russian Navy warships and Russian soldiers on an auxiliary fast boat in Sevastopol, 2019.

Arthur Bondar

Border guard patrol boats and a brand new Russian battleship in Sevastopol Bay in Crimea, 2019.

Arthur Bondar

As I look back on my experiences dealing with both Russia and Ukraine, three factors stand out.

First, most Russian officials with whom I worked when I was ambassador in Moscow had a limited understanding of how Ukraine has changed over the past three decades. Serving in Ukraine immediately before the Russian seizure of Crimea and aggression in the Donbas, and then serving in Moscow for three years soon thereafter, brought home to me on an almost daily basis the gap between the mythic Ukraine and the reality of modern Ukraine. Russians often looked at their Ukrainian “cousins” through an imperial prism and did not recognize the true nature of independence that has developed in the nation.

In particular, many of the assumptions underlying Russia’s invasion of the Donbas were mistaken, notably that Ukraine’s Russian speakers all wanted to be a part of Russia. For example, the idea that Russian-speaking ethnic Ukrainians living in southern Ukraine bordering the Black Sea would welcome becoming a part of a land bridge linking Crimea with Donbas as part of a new “Novorossiya” was based on the mistaken notion that these people wanted to be a part of a “New Russia.” This idea is rooted in a history of the conquest of this region by Catherine the Great and Potemkin in the 18th century, and bears little resemblance to contemporary Ukraine. Moreover, I don’t believe most official Russians have any real understanding of the attitudes of Ukrainian young people.

Second, Vladimir Putin and the elite currently ruling Russia still cling to the notion that Russia can reassert its imperial-style control over Ukraine, Georgia and other independent nations of the former Soviet Union. While the annexation of Crimea was extremely popular inside Russia in the aftermath of the invasion, the people seem to be tiring of the unending war in the Donbas and the steadily declining standard of living that has characterized Russia since 2014. This was caused, in part, by the imposition of economic sanctions by the West as a response to Russian aggression.

Third, underlying the Russian-Ukrainian struggle has been an effort in both countries to find a new post-Soviet national identity in the modern world. Beyond the larger geopolitical struggle, the quest to define who is a modern Russian and who is a modern Ukrainian has turned out to be a long process. The conceptions and myths involved in this effort in both countries are many. Both want to root their national identity in the past, but the future they then envision for their nation is starkly different. Putin and the ruling elite of Russia see the future as a resurrection of their country as a great power, with imperial-style sway over their former dominion (it is unclear how many Russians share this view). Ukrainians, on the other hand, see their future as a part of Western politics and culture, as the geopolitical pivot between East and West.

U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and members of the U.S. delegation at a U.S.-Russia bilateral meeting in Moscow on April 12, 2017. Right to left: U.S. Ambassador to Russia John Tefft, interpreter Marina Gross, Secretary Tillerson, Chief of Staff Margaret Peterlin, and senior advisers Brian Hook and R.C. Hammond.

U.S. Department of State

With U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry looking on, Russian President Vladimir Putin, at right, greets U.S. Ambassador John Tefft prior to their meeting in the Kremlin on Dec. 15, 2015.

U.S. Department of State

The process of emerging Russian and Ukrainian national identities was aptly characterized by New York Times correspondent Neil MacFarquhar as “the statue wars” in a Nov. 4, 2016, article. On that day, Russian President Vladimir Putin unveiled a nearly 60-foot-high statue of his namesake, Prince Vladimir the Great, in Borovitskaya Square just outside the Kremlin Walls in Moscow. Russian Patriarch Kirill stood by his side. In light of Russia’s 2014 seizure of Crimea and military incursion in eastern Ukraine, the unveiling was viewed by many analysts as a symbolic reassertion of Russia’s nationalist claim not only to empire, but also to being the political and religious heir of the Kievan Rus, the loose confederation of East Slavic and Finnic peoples who inhabited the region from the ninth to the 13th centuries. Vladimir is celebrated not only as a great political leader of the Kievan Rus, but as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church. His baptism in Crimea around 988 brought Christianity to the Slavic peoples of the region and is used by Moscow to justify its claims to Crimea.

In Kyiv, meanwhile, another statue of St. Vladimir (in Ukrainian, Volodomyr) has stood since 1853 on a historic bluff high above the Dnipro River. St. Volodomyr is celebrated by the Ukrainian people as the Grand Prince of Kyiv, the father of the Ukrainian nation. They point to the creation of Kyiv and other cities in the region during the 11th century—long before Moscow became a city of power and money—as evidence of their true inheritance of the legacy of Volodomyr and his family. They, too, celebrate St. Volodomyr for Christianizing the Kievan Rus and point to Saint Sophia Cathedral, built in central Kyiv in the 11th century, as the main focus of orthodoxy in the region. Reflecting a new sense of ecclesiastical independence from Moscow, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (which had broken with the Russian Orthodox Church once Ukraine regained independence in 1991) was formally recognized as autocephalous or independent by the Patriarch of Constantinople in 2018.

Russian actions in Crimea and the Donbas in 2014 caused a sharp drop in the number of Ukrainians who had a positive attitude toward Russia.

The problems between Russia and Ukraine will require many years to resolve. In so many ways they reflect the challenges of the continuing post-Soviet transformation of Eastern Europe. Understanding the causes of the Russo-Ukrainian dispute and finding solutions will require patience and steady diplomacy by the United States and the members of the European Union. We have a vital interest in seeing the war in the Donbas come to an end in a way that fully preserves Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

We also have a vital interest in helping Russia and Ukraine learn to live with each other in the modern world. Unchecked, Russian revisionist policy in Ukraine will continue to undermine the future of European security and the postwar order in which we have invested so heavily. Similarly, continuing to support the internal reforms in Ukraine that President Zelensky has promised, and maintaining strong bipartisan support for Ukraine’s path forward, will remain essential if we are to help this key nation achieve its potential and become a true model in a Europe whole, free and at peace.