Soviet Union, Russia and Ukraine—From the FSJ Archive

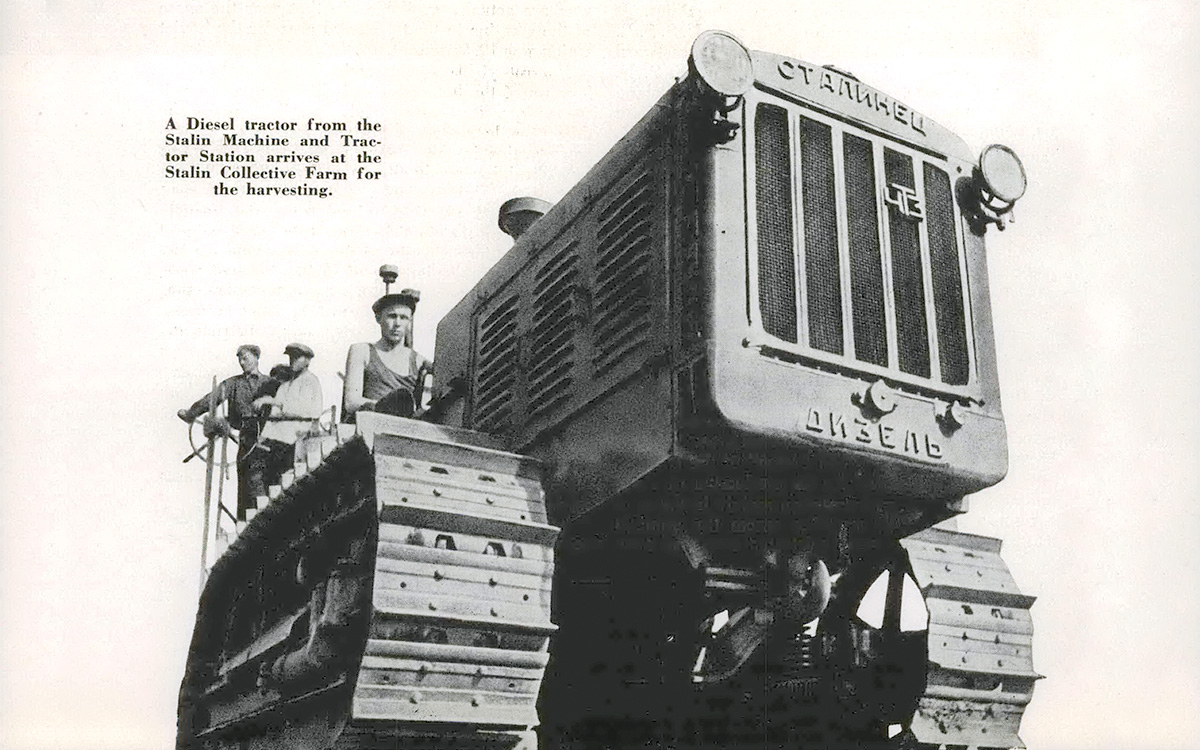

From “The Soviet Ukraine: Its Resources, Industries, and Potentialities,” by E.C. Ropes, August 1941

We Recognize the Soviet Union

Ambassador Bullitt then presented his credentials to President Kalinin on December 13 [1933]. Mr. Bullitt was accompanied by Mr. Joseph Flack, First Secretary at Berlin, and Mr. George F. Kennan, Third Secretary at Riga.

Mr. Bullitt said in part: “That mission, Mr. President, is to create not merely normal but genuinely friendly relations between our two great peoples, who for so many years were bound to each other by traditions of friendship. The firm establishment of world peace is a deep desire of both of our peoples, and the close collaboration of our governments in the task of preserving peace will draw our peoples together.”

—Walter A. Foote, January 1934

Contacts with the Soviets

It is diplomacy by culture—but a cultural diplomacy subject to a central plan, in which even the arts and sciences serve the Party line first and foremost. …

There is already in the last year an observable decline in the ignorance and prejudice with which the Soviet and non-Soviet worlds regard each other, and there is a tendency to meet exaggerated propaganda with a certain degree of disbelief. The forty-year freeze in cultural relations between the two countries could well be melting. If so, the Soviet citizen may gradually have more opportunities to test his beliefs against direct observation, thus breaking out from the intellectual isolation in which he has found himself. For isolation is dangerous to any country in a world Community where the free communication of ideas means progress if not salvation.

—Frederick T. Merrill, March 1959

Russia and the West

If the West is successfully to thwart the communist dream of universal empire, it is less important for us to know why the Soviet leaders wish to “bury” us than to know how they propose to do it. It is very clear that they do not intend to leave the process to the mystical force of history, however “inevitable” its outcome. They are going to help the process along with all of their resources and it is the task of Western statesmen to estimate what those resources are, the way in which they have been used in the past, and how they are likely to be used in the future.

It is all the more essential, under these circumstances, that we develop widening channels of communication, of cultural and educational exchange, between the two societies. … It is at least possible that the cumulative impact of the real world of experience on the imaginary world of Marxian dogma will gradually bring about profound changes in the latter.

—J.W. Fulbright, October 1963

Eastern Europe: The Unstable Element in the Soviet Empire

Soviet control of most of Eastern Europe has given it forward military bases and possession of the traditional invasion routes into Europe. The Soviet position constitutes a kind of pistol at the head of the West. The peoples and resources of the area increase Soviet economic and military power. Soviet control over Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, and Poland appears tighter and firmer than ever before. …

Our economic and military strength is so vast that we do not understand its significance, while our power when added to that of our allies almost staggers the imagination. However, our greatest strength is almost invisible, because it is the social vitality, the effervescent intellectual vigor, and the freedom and openness in which we live and face our serious problems.

The central position in our foreign policy should remain the peaceful reconstruction of Europe. This should be accomplished without alarming the Soviet Union but providing the states and peoples of Eastern Europe with the independence and right to self-determination which they deserve and seek.

—Robert F. Byrnes, July 1971

Ambassador to the USSR, 1952

At first he [George Kennan] endured Soviet regulations, including those that precluded travel more than 25 miles outside of Moscow, forbade him to speak with Soviet citizens, and required him to purchase most Soviet publications through the Foreign Ministry.

When Kennan served in Moscow during the 1930s and 1940s, he had friends among the Soviet employees at the embassy, but in 1952, the stone-faced servants at Spaso House shunned communication, groundskeepers declined to work, and security officers followed Kennan wherever he went, depriving him of enjoyable strolls among the Russian people. “I came gradually to think of myself as a species of disembodied spirit,” recalled Kennan, “capable, like the invisible character of the fairy tales, of seeing others and moving among them but not of being seen, or at least not of being identified by them.”

Kennan told his colleagues that he still favored an eventual diplomatic solution with Moscow over Korea, Berlin, and other issues. “I would negotiate with the Soviet representatives coldly and brutally and in full acceptance of the fact that their ultimate aim is to ruin us, and that they believe our ultimate aim is to ruin them.”

—Walter L. Hixson, May 1987

Moscow Today: An Interview with Arthur Hartman

The U.S.S.R. is a closed society, and our purpose in being in Moscow is to understand and report on it as fully as possible. So we have to balance the risk and the opportunities. We want our people to know how to handle themselves and to engage, to get out and talk to Soviets and to do what you can only do on the spot in Moscow.

On the human side, we read reports in the press that the abrupt removal of local employees necessitated having political officers, for instance, scrub toilets and do other housekeeping chores. What has it been like? … Well, we found out because we were the only embassy in the world that actually operated—and is still operating—without any local employees.

When will our operations in the Soviet Union return to normal? Moscow is a very abnormal place. We are going to have to establish a balance between making sure our people are not open to security risks and making sure that they can still get out and observe Soviet society.

—May 1987

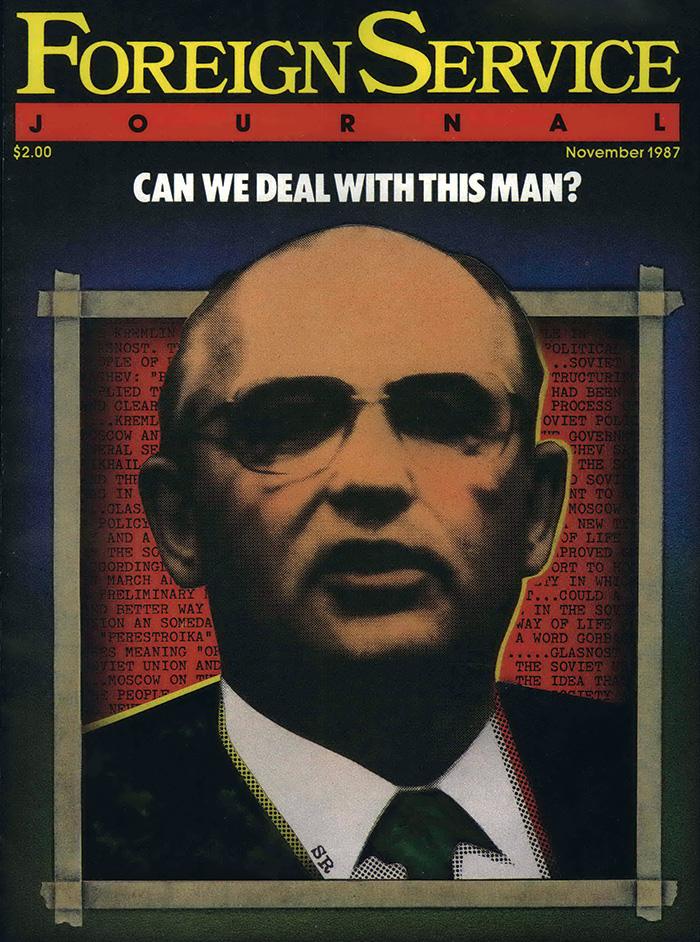

The Perils of Perestroika

Following the deaths of three aged Soviet leaders in three years, the selection of Mikhail Gorbachev as general secretary of the Communist Party was an extraordinarily important event. In Gorbachev, the U.S.S.R. not only has a vigorous leader in his 50s, but an individual of considerable political talent and intellectual acumen. Almost without exception, those who have talked with the new general secretary have found him to be intelligent, well informed, and purposeful. His style of “openness,” his criticisms of many Soviet traditions and methods, and his proposed solutions, if implemented, will result in profound changes for Soviet society. Gorbachev has set for himself a surprisingly difficult agenda: reinvigorating economic performance, civic consciousness, and, most broadly, public morality. The outcome of this program, however, is very much in doubt.

His hidden agenda was a widespread assault on accumulated privileges, waste, corruption, and laziness. The anti-alcohol campaign bought him time, while beginning the kind of sociopolitical regeneration he was seeking.

Far beyond the borders of the Soviet Union, the unfolding of perestroika and glasnost may affect the whole Eastern bloc. On the other hand, if the reforms implicit in these terms are not realized, then both perestroika and glasnost could be harbingers of political entropy, with egregious consequences for the Soviet people as a weakening superpower senses its own peril. That the potential of his ideas may not be realized is understood most fully by Gorbachev himself.

—Daniel N. Nelson, November 1987

Helping Russia Reform

Our attitude should be one of partnership on a very long journey of trial and error—not to impose our vision of the Good Society on Russia, but to improve life for the Russian people in ways they consider helpful. If we are perceived to be a concerned, friendly country without an ideological axe to grind, we will be more successful in addressing the problems in our relationship, which will inevitably arise.

We should continue to treat Russia as a great power, without condescension. … The Russian leader needs to be treated, however, as someone who is cooperative with the United States for his own hard-headed national reasons and in no way someone we can take for granted.

The Clinton Administration should assume that: It may well end up paying more to Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Belarus for implementation of START I and II and the storage and destruction of nuclear weapons than it anticipated, but it will be a small price to pay for maintaining forward momentum in our arms control programs.

—Thompson R. Buchanan, April 1993

New Era Beckons for Ukraine

When Leonid Kravchuk was head of ideology in Soviet Ukraine, he would arrive at his office at 9 a.m. At 9:30 a.m. he would receive a phone call from Moscow with the day’s instructions. After the call, he would pick up another phone, pass the orders to the party cadres, and his work for the day was done. As president of an independent Ukraine, Kravchuk laments that the problem with Ukraine is that the phone from Moscow no longer rings. This story, while apocryphal, does underscore the many challenges Ukraine faces. It is a new country devoid of much of the infrastructure necessary for organizing and leading a country. Its leadership, products of the Moscow-centered decision making of the Soviet era, is more comfortable with carrying out rather than creating ideas and goals.

Long known as the breadbasket of Europe, Ukraine had been an economic mainstay of its colonial rulers, most recently the Soviet Union. Many believed its size, its location and its agricultural and mineral resources destined it to be a leading regional actor. Thus, as Ukraine moved towards independence, there were high expectations that its leaders would quickly take advantage of its potential and blossom politically and economically.

Located at the crossroads between Europe and Asia, defended by no natural borders and blessed with rich agricultural soil, Ukraine has historically been the target of aggression or the site of empires fighting out colonial drives. None of the occupations have been conducive to Ukraine’s development. Indeed, they have aimed at destroying Ukrainian identity. …

Ukraine’s concern regarding Russian intentions is understandable. But there is another dimension. Pressed from various sides, Ukraine has historically sought to maintain its security by appealing to or allying itself with outside forces, since it never has had the internal experience or resources to maintain its own security.

—Roman Popadiuk, June 1994

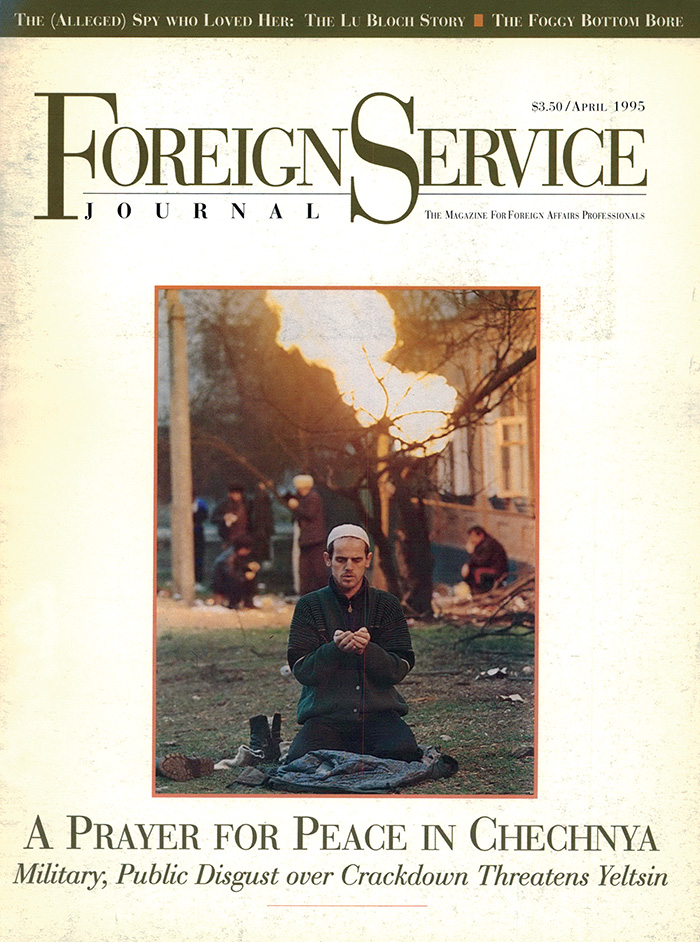

The Plummeting of Yeltsin’s Star

In fact, the terrible performance of the Kremlin in this war [Chechnya] has dramatically changed the political situation in the former Soviet Union. …The developments in Chechnya also have uncovered deep disarray of the Yeltsin administration. … Numerous times in the last month, the administration has proclaimed victory, even as Russian casualties continued to mount. … The Chechen war has also drastically damaged the international image of both Russia and Yeltsin.

—Vladimir Shlapentokh, April 1995

Oral History in Real Time: The Maidan Revolution

“Bearing witness to the fact that this was a movement of the people for the people, a movement of dignity, self-organized—to bear witness to what the government’s troops were doing or not doing. … I think it was an extraordinary time, when you saw resources and people coming together, and to explain that and to convey that to Washington was important. [It was important] to say it’s not just any old protest. And to explain also that there were some fundamental values that people were supporting, and why it was in our interest to help make sure that there was a space for people who were protesting, that there was a democratic way to do this. That’s what I think our role was—and the role of the diplomat.”

—Joseph Rozenshtein, April 2017 (quoting Deputy Economic Counselor Elizabeth Horst, 2014)