The Putin Doctrine and Preventive Diplomacy / The Need for Consensus on American Goals

The USSR is not coming back, but the United States must take a realistic approach to Russia, correctly framing the issues and wielding the tools best suited to strategic priorities.

BY JAMES E. GOODBY

Ambassador James Goodby (seated, left) and Ukrainian General-Lieutenant Aleksey Kryzhko initial a Nunn-Lugar agreement with the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine in 1993 in Kyiv to provide assistance for the elimination of strategic nuclear arms.

Courtesy of Royal Gardner

Vladimir Putin announced his strategic doctrine regarding “post-Soviet space,” as he calls the lands of the former Soviet Union, early in his first presidency and has stuck with it ever since. In a speech to the Russian Federal Assembly on May 16, 2003, he declared: “We see the [Commonwealth of Independent States] area as the sphere of our strategic interests.”

In his April 2005 speech to the same body, Putin called for unanimity within the Commonwealth of Independent States, hailing the World War II victory that unity had made possible. Though he did pay lip service to the independence of the CIS nations and their “international authority,” he hinted that independence from Russia was not quite what he had in mind: “We would like to achieve synchronization of the pace and parameters of reform processes underway in Russia and the other members of the CIS.” In other words, Moscow wanted a say in, if not a veto over, how fast political change took place in neighboring states, and what form it would take.

In the same speech, Putin made his famous comment: “The collapse of the Soviet Union was the major geopolitical disaster of the [20th] century,” adding that “the epidemic of disintegration [had now] infected Russia itself.” Putin’s domestic policies, his hard line in Chechnya and, later, in Georgia, and his regional diplomacy all testify to his belief that Russian pre-eminence in “post-Soviet space” is an indispensable element of the defense of the Russian Federation. Ukraine is only the latest and most dangerous manifestation of the Putin Doctrine. It will not be the last.

Exercising Preventive Diplomacy?

The clarity of the Putin Doctrine meant that the current crisis in Ukraine—or, more accurately, the crisis in U.S.-Russian relations—was foreseeable. The 2008 war between Russia and Georgia added an unmistakable warning, but its significance quickly vanished among the “frozen conflicts” that littered so many territories of the former Soviet Union.

Military force cannot be the first thing to come to the minds of policymakers for handling such challenges. Preventive diplomacy—which the United Nations defines as “diplomatic action to prevent disputes from arising between parties, to prevent existing disputes from escalating into conflict and to limit the spread of conflicts when they occur”—should be the first resort, but it is exceptionally difficult to sustain. No government likes to borrow trouble from the future, and democracies, including the United States, are very poor at setting strategic priorities and sticking to them.

The American stance under Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama was that Moscow should have considerable say in its neighboring states, and Washington should not seek to supplant that influence. Georgian and Ukrainian membership in NATO, for example, should not have to damage their good relations with Russia. In the face of much evidence to the contrary, successive administrations thought that Moscow should understand that Russia would benefit from having prosperous, democratic nations in its neighborhood. The Kremlin interpreted NATO’s November 2002 decision to invite seven new members to join the alliance, including the three Baltic states, as taking advantage of Russia’s weakness. The later American decision to deploy ballistic missile defenses in Poland and the Czech Republic only heightened Russian insecurity.

President Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry have contrasted their enlightened, 21st-century point of view with the zero-sum, 19th-century thinking that has characterized Russian diplomacy. Putin was not persuaded by rhetoric, and the West failed to formulate a new strategic or institutional framework to match 21st-century challenges, although plenty of ideas were out there.

For example, in 2002, the U.S. Institute of Peace Press published a book titled A Strategy for Stable Peace: Toward a Euro-Atlantic Security Community. It was written by a Russian, Dmitri Trenin, a Dutchman, Petrus Buwalda and an American—myself. We wrote that “Ukraine must solve its internal problems through its own efforts” and “the stakes in the outcome of Ukraine’s struggles are high, not least the progress of Russia and the West toward a stable peace.” We called for “concerted national strategies on the part of the major nations within the extended European system.”

In defining these strategies, we argued that a detailed master plan is not realistic, and that “governments should work with building blocks already available to them, having their objective clearly in mind.” The long-term objective, we thought, should be the inclusion of Russia as one of three pillars, with North America and the European Union, of a Euro-Atlantic security community, sharing similar democratic values.

In 2012, a study of mutual security in the Euro-Atlantic region was conducted, led by four distinguished statesmen: former German Ambassador to the United States Wolfgang Ischinger, former U.K. Defense Minister Desmond Browne, former Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov and former Chairman of the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee Sam Nunn. Their advice, in a spring 2013 report, “Building Mutual Security in the Euro-Atlantic Region,” included the establishment of a new, high-level “Euro-Atlantic Security Forum” to promote core security interests throughout the region. Common to this report and the 2002 book on the same subject is the notion that this geographical construct should be thought of as a single security space in the long term.

The Permanent Revolution

Back in February 2005, alluding to recent unrest in Georgia and Ukraine, Putin speculated that some nations “are doomed to permanent revolution. ... Why should we introduce this in the post-Soviet space?” The answer, of course, is that those governments refused to meet pent-up demand for changes, leading to a series of political explosions—which Putin accused Russia’s old antagonist, the United States, of fomenting.

Putin’s belief in American complicity in the “permanent revolution” had first surfaced during a Nov. 26, 2004, press conference in The Hague. Discussing the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, he remarked: “We have no moral right to incite mass disturbances in a major European state. We must not make solving disputes of this nature through street disturbances part of international practice.”

Such warnings about permanent revolution stemmed from his perception of Russia’s weakness and its possible fragmentation. On Sept. 7, 2004, after terrorists killed nearly 400 people, many of them schoolchildren, in Beslan, North Ossetia, he said: “Some would like to tear from us a ‘juicy piece of pie.’ Others help them. They help, reasoning that Russia still remains one of the world’s major nuclear powers, and as such still represents a threat to them.”

Later in the same speech, Putin remarked: “We are living through a time when internal conflicts and inter-ethnic divisions that were once firmly suppressed by the ruling ideology have now flared up.” Russia had not reacted adequately to these new dangers, he lamented; instead, “we showed ourselves to be weak. And the weak get beaten.”

In other words, Moscow must show itself to be tough, even at the expense of its own best interests. Any step back from dominance over the new nations of “post-Soviet space” would be tantamount to encouraging the disintegration of the Russian Federation itself. Similarly, compromises with Russia’s enemies are a slippery slope that can only lead to a serious weakening of its international and domestic position.

No government likes to borrow trouble from the future, and democracies, including the United States, are very poor at setting strategic priorities and sticking to them.

A New Iron Curtain?

The last straw for Putin was probably his conclusion that the West was determined to prevent him from realizing his vision of a Eurasian economic bloc, dominated by Russia, that would include at least Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan. When Ukraine’s pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych, seemed ready last fall to sign an association agreement with the European Union, Moscow pressured him to reverse the decision. Putin saw an American hand behind the resulting popular uprising that ousted Yanukovych.

A desire to have friendly neighbors on one’s borders is not unique to Russia, of course. Nor is it unusual for a powerful state to expect that its opinions and interests will exert considerable influence on the policies of neighboring states. But there is a line beyond which a special relationship becomes domination. If things remain as they are in Putin’s Russia, the reality of a continent divided will congeal, leaving most of the newly independent republics trapped on the other side of the fence from a democratic Europe.

This appears to be exactly what the Putin Doctrine is intended to achieve. Writing in the July/August issue of Foreign Affairs, Alexander Lukin, vice president of the Diplomatic Academy of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, noted that some in Moscow are searching for an ideological foundation for a Eurasian union. Lukin wrote that the distinctive value system of Eurasian people had helped Putin “succeed in establishing an independent power center in Eurasia.”

Putin and the “siloviki”—his former colleagues in the KGB who now occupy key positions in the Russian government—are disposed to confront Washington if American activities seem to be encouraging too much independence within “post-Soviet space.” Putin’s rollback of the democratic institutions in Russia that his predecessor, Boris Yeltsin, had encouraged underscores the fact that joining a Western-oriented community is not one of Putin’s strategic objectives. He is positioning his nation so that it cannot truly be part of Europe in the sense of shared values and shared self-identification.

Challenge to the Post–Cold War Order

The question for the West is how to conduct order-building diplomacy in the midst of a major crisis stemming from Putin’s increasingly evident intent to separate eastern Ukraine from the rest of the nation. His “New Russia” rhetoric has a serious meaning to it. The order that is being challenged is enshrined in the Helsinki Final Act of 1975, which amounted to a surrogate peace treaty to end World War II. That document was strengthened by a series of agreements over the years negotiated within the framework of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (later the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe).

Other agreements that shaped post–Cold War Europe dealt with the emergence of new sovereign nations after the breakup of the Soviet Union. One of the most important of these agreements figured in a CSCE summit meeting held in Budapest in 1994. It was the Lisbon Protocol to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, and it changed the adherents to that agreement from just the Soviet Union and the United States to Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Russia and the United States.

At Budapest, the three new signatory states formally agreed to become non–nuclear weapon states and to join the nuclear nonproliferation treaty in that status. A statement of assurance regarding its territorial integrity within existing frontiers was presented to Ukraine by the presidents of Russia and the United States and the prime minister of the United Kingdom, and also subscribed to separately by China and France. The five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council thus became parties to these assurances of Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

The provisions of the Helsinki Final Act that upheld territorial integrity and forbade changes in frontiers except by peaceful means also applied to the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union. The Final Act begins with 10 principles, of which the first two deal with sovereign equality and refraining from the threat or use of force. The text of the second principle states: “No consideration may be invoked to serve to warrant resort to the threat or use of force in contravention of this principle.”

This is the order that President Putin has challenged. There are really only two choices before the members of the Helsinki accords: accept that an all-European order with common understandings no longer exists and act accordingly; or try to reverse what Putin has done and work to restore the Helsinki consensus. The former course means a division of the Euro-Atlantic region into Eastern and Western societies and is the course less likely to lead to conflict in the near term. This appears to be Putin’s strategic aim.

The latter is the policy that the Western nations say they are pursuing. But to succeed, the West must be willing to impose stronger sanctions and provide military assistance to Ukraine and possibly other neighbors of Russia if it is to succeed. Clearly, this policy has its risks; but in an age of globalization, sustaining the order laid down in the Helsinki Final Act is fundamental to order-building diplomacy. If carefully calibrated as to the tools employed and seen as a long-term strategy, it has a very good chance of success.

The division of Europe into opposing camps would have consequences for relations between the West and Russia long after Putin leaves the scene. Re-creating the polarized structure of the Cold War runs against the grain of history, in my view.

Putin’s efforts to turn back the clock seem unlikely to succeed, no matter how fervently he evokes nostalgia for Russia’s historical borders.

Framing the Issues Correctly

The first step in devising guidelines for future U.S. strategy is to frame the issues correctly. For example, it would be wrong to think that Russia is the origin of all the problems in the enormously complex mix of ethnic groups that inhabit the regions around its borders and also within the sprawling country. True, Moscow is an enabler of separatist movements in eastern Ukraine, and elsewhere, and seems to find that divide-and-conquer policies suit its needs. But it would be simplistic to think that if Moscow suddenly became cooperative, all would be well.

Because of the emotions and the long histories involved in all these disputes, it will take time before trust takes root between central governments and those ethnic groups inclined toward independence. The diplomacy of “gardening”—patient and prolonged engagement—is the only way to deal with these situations.

Framing the issues correctly also means an accurate assessment of where Putin may be heading and where Russia might be able and willing to follow. Putin’s actions in Ukraine and his domestic crackdown on dissent are certainly reminiscent of the Cold War, or worse. Some have even compared this period to pre–World War II. But Putin’s Russia is not Stalin’s Russia, and the world of 2014 is notable for the many ways in which the international system itself is changing under the impact of globalization and the rise of social media.

Seen in the light of megatrends dominating the global landscape today, Putin’s efforts to turn back the clock are unlikely to succeed, no matter how fervently he evokes nostalgia for Russia’s historical borders. Autarky simply is not a viable economic policy for Russia in the age of globalization. The people-to-people links between Russia and the West will not easily be severed, especially with information and global communication so easily available to ordinary citizens.

A reasonable interpretation of events is that Russia is undergoing the trauma of a lost empire, not dissimilar to the withdrawal pangs of other former imperialist powers. Like other post-imperial powers, Russia is having trouble adjusting to its changed status. It still believes that it should not only have a privileged position in the nations that once were part of the czarist, and then Soviet, empires, but also that it can exclude political or other changes of which it disapproves. But no more than other European nations could re-establish their “blue water” empires will Moscow be able to re-create the Soviet Union or the Russian empire on the land mass of Eurasia. So what we are seeing is most likely part of the long recessional march from empire, made more complex by the reactionary romantic in the Kremlin.

Accuracy in framing the issues also requires an understanding that American diplomacy in Russia’s neighborhood is only part of the total picture. On the positive side, the attraction of the European Union for all of Russia’s neighbors is hard to overstate. Political and economic reforms are the price for an association with it—something most of Russia’s neighbors accept, albeit with reluctance in some cases. On the negative side, the vulnerability of European countries to the threat of a cutoff of Russian oil and gas renders them less capable of assisting nations adjacent to Russia. China also will exert some influence, and so will the situations in Afghanistan and the Middle East.

Beyond framing the issues correctly, American policymakers need to balance the twin American interests in good working relations with Russia and encouraging democracy and freedom throughout Eurasia. In principle, such policies should be compatible, especially within a policy framework designed to promote a Euro-Atlantic security community, including Russia, based on common values and a broad sense of a common identity. This is a multigenerational strategy, as containment was during the Cold War; but it is a positive, inclusionary vision, worthy of the West.

If this strategy is pursued, the political changes that already have appeared in “post-Soviet space” and those yet to come will eventually succeed in transforming the frozen political landscape where heated emotions lie not far beneath the surface. The interrupted march toward a Europe that is peaceful, undivided and democratic will be resumed, and Russia ultimately will join it. But this is not Putin’s vision of the future, and probably never has been. He has left no doubt about this.

Preventive Diplomacy: Another Chance?

The optimism of the first years following the end of the Cold War has given way to skepticism, even cynicism, about Russia’s place in Europe. Disillusionment with the “reset” policy has added to the sense of helplessness. To renew the interrupted march toward a Euro-Atlantic community of democracies will require a major act of Western and, yes, Russian statecraft. But failure to rise to the occasion will mean that the turning point in history that began with the Cold War’s end will become only another sad story of frustrated hopes leading ultimately to catastrophe. An American strategic approach that correctly frames the issues, and wields the tools best suited to strategic priorities, will be essential to the successful exercise of preventive diplomacy.

Realism requires an understanding that internal conditions in Russia, and Moscow’s policies toward its former dominions, are likely to stand in the way of its full inclusion in a Euro-Atlantic community for a long time to come. Events in Ukraine and Putin’s crackdown on Russian dissent have underlined this.

So why pursue a vision that the present Russian government almost certainly does not share? Because it provides a magnetic north for a policy compass that easily could become confused and directionless in the face of conflicting interests. In addition, failure to seek Russia’s ultimate inclusion in a Euro-Atlantic security community would slow down political change across the region, erect new walls and weaken the international response to global threats to humanity.

Preventive diplomacy, crisis management and order-building diplomacy all need to be merged to meet the current challenges represented by Ukraine. Resorting to the mechanisms established to support the undertakings of the Helsinki Final Act will help. Reasserting the validity of the vision of Euro-Atlantic relations held forth by the Final Act is an absolutely bedrock policy for the United States, no matter what strategy Washington chooses to pursue.

In current circumstances, managing the crisis over Ukraine requires the West to rally around this vision and encourage Russia to honor it, as well. The agreement that created the organizational machinery of the OSCE provided for ministerial meetings on a regular basis and also for summit meetings, to be held on an as-needed basis. Pres. Obama would do well to invite the OSCE heads of states or governments to convene early in 2015 to discuss the situation in Ukraine and, more fundamentally, to reaffirm that all members of the OSCE intend to abide by its principles of behavior as laid down in the Final Act. Possibly a new high-level Euro-Atlantic security forum of the type recommended by Ischinger, Browne, Ivanov and Nunn in their 2012 report could also be discussed in an OSCE summit meeting. That forum could be a useful adjunct to the OSCE in a way analogous to the U.N. Security Council and the General Assembly.

Russia is undergoing the trauma of a lost empire, not dissimilar to the withdrawal pangs of other former imperialist powers.

The Challenge of Governance

As chief negotiator for the Nunn-Lugar program of cooperative threat reduction, I had a direct hand in negotiating U.S.-Ukrainian agreements that led to Kyiv’s decision to surrender the nuclear weapons left on its territory after the breakup of the Soviet Union. My counterpart was a highly competent Ukrainian general-lieutenant. Before we appended our initials to each page of the agreement that promised U.S. assistance in expediting the destruction of nuclear delivery vehicles, my colleague spoke very earnestly to me: “I lay awake last night wondering whether I could trust you. I finally concluded that I could.”

His comment brought home to me the stakes for Ukraine in initialing that agreement. I have thought of that moment frequently in recent months, wondering whether we lived up to the general’s trust.

What I see is an American foreign policy establishment that lacks the capacity for consistent strategic analysis and policymaking. Decisions at the White House have tended to be ad hoc and personalized. During my time in the U.S. government, it was this way more often than not. The Eisenhower administration was an exception. Ike used to say: “Plans are nothing; planning is everything.” The Nixon and Ford administrations believed firmly in top-down policymaking, and Henry Kissinger used the National Security Council apparatus to good analytical effect. These administrations were the butt of jokes for their perceived overuse of the analytic process, but that process was useful as an educational tool, both up and down the ladder of authority and responsibility.

Strong and visionary Secretaries of State, like Dean Acheson and George Shultz, who enjoyed the confidence of the presidents they served, have devised and executed highly successful strategies. President Harry Truman and Acheson, for example, worked closely to create the institutions that dominated trans-Atlantic and even global relations throughout the Cold War. Three decades later, President Ronald Reagan and Shultz laid the basis for the end of the Cold War through an approach based on realism: strength, not only in military and economic capabilities but also in resolve; and a firm and consistent agenda with which they continued to engage with the Soviet Union through good times and bad. They believed that the Soviet Union would change, a belief that needs to be the bedrock assumption of American policy in the era of Putin.

Preventive diplomacy is the functional equivalent of deterrence, and it is more necessary than ever in an era when nuclear deterrence is less relevant to today’s threats than it was at the height of the Cold War. I think that the best way to make preventive diplomacy work and to justify my Ukrainian colleague’s trust in the seriousness and constancy of U.S. policy would be to build an improved institutional capacity in the foreign policy machinery for serious analysis and for the setting of strategic priorities. It must operate at the highest levels of government.

If the United States followed the advice offered by former Secretary Shultz to make greater use of clusters of Cabinet secretaries with similar functional responsibilities to consider policy issues, and less use of White House “czars,” that would help enormously. But the culture of Washington may have to change, too—a difficult proposition. Preventive diplomacy cannot work in the absence of agreed, long-term strategic objectives. It would be like deterrence without a target.

The Need for Consensus on American Goals

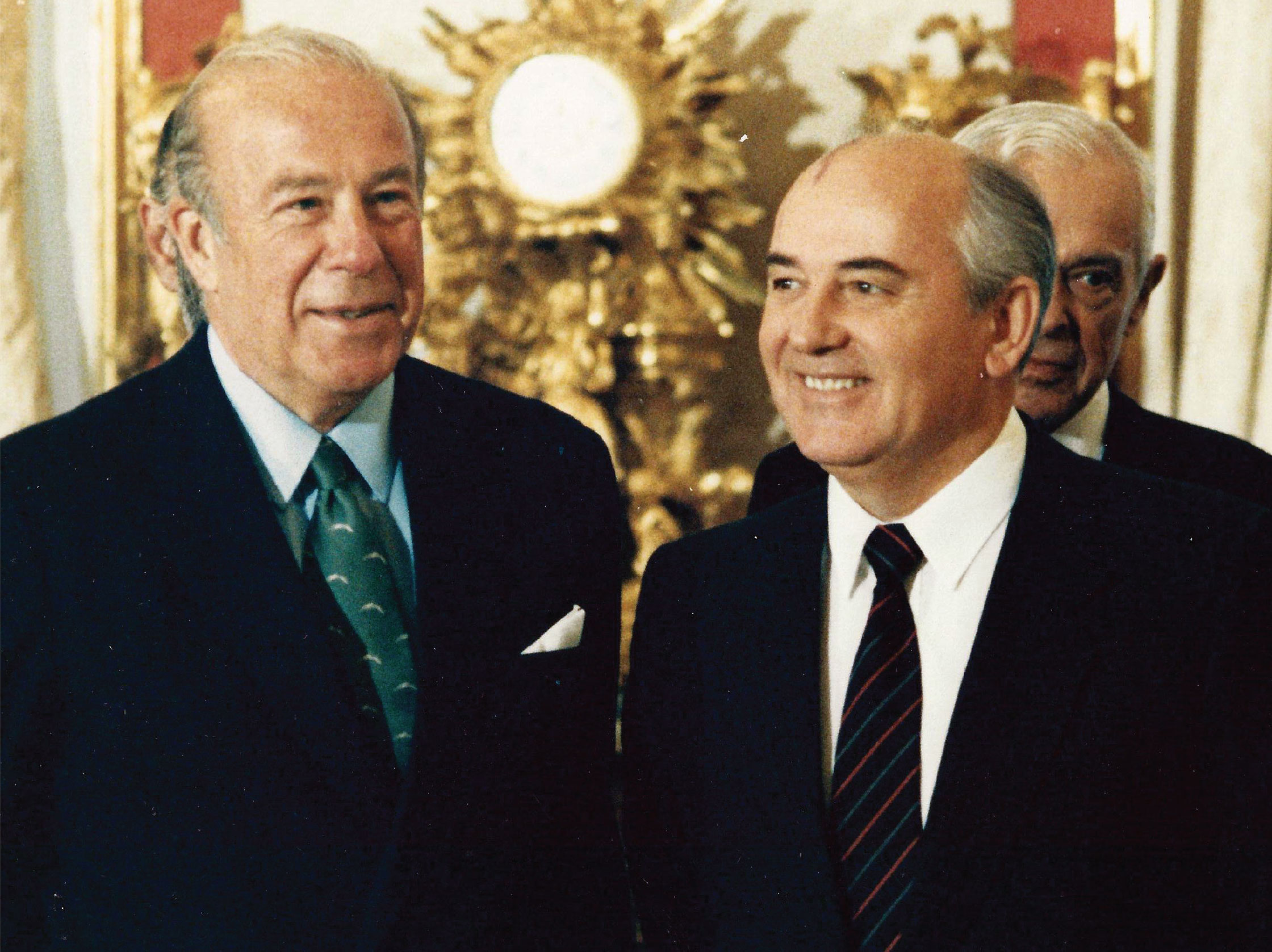

U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz with General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev in the Kremlin, meeting to finalize the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Paul Nitze is behind Gorbachev. Moscow, Oct. 23, 1987.

Courtesy of the Hoover Institution

The changing climate and its effect on our environment, the civilization-destroying effects of nuclear war and the enhanced possibilities of global pandemics are only three examples of challenges that require an unprecedented degree of cooperation, and not just between national governments but among peoples.

In this essay, Ambassador Goodby describes what he calls “the Putin Doctrine”: a coherent set of actions consistently applied over many years, designed with a specific, overriding goal in mind. That goal seems clear now, in light of the risks Russian President Vladimir Putin has been prepared to take to achieve it: to ensure Moscow’s dominance over as many of the former republics of the Soviet Union as is feasible given Russia’s resource limits, and to incorporate them, and those too strong to dominate, into a regional economic and political bloc led by Russia that is capable of exerting global influence.

That strategic objective may not be achievable by Moscow for a host of reasons. But its pursuit can skew the way the international system shapes up in the future by holding out the model of a set of competing, relatively closed regional blocs, run by authoritarian systems of governance.

Americans will have to rise to the occasion by building a consensus, hard as that may be, around our own goals in a world awash in change. Though I don’t sense that there is a consensus on that at the present time, I believe most Americans would agree that the United States must stand for open societies and for the rules embodied in the Charter of the United Nations and in regional compacts, such as the Helsinki Final Act. That is fundamental so long as nation-states remain central to the structure of the international system.

But beyond that, we must be actively seeking to build institutions, whether global or regional, that can respond to challenges to humanity’s well-being and even its survival. The goal of that kind of policy and that kind of diplomacy, quite simply, is to position our nation to continue to thrive in the new world.

–George P. Shultz, former Secretary of State,

October 2014

Read More...

- Dr. James E. Goodby: American Diplomacy in Russia’s Neighborhood (The Commonwealth Club of California)

- The End of a Nuclear Era (The New York Times, The Opinion Pages, Aug. 14, 2013)

- Repairing U.S.-Russian Strategic Relations after Bush and Putin (Arms Control Association Press Briefing, April 11, 2008)

- Nunn-Lugar Revisited (National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 447)

- Sam Nunn: National Security Visionary (FSJ, September 2009)

- Putin fiercely guards reach of ‘post-Soviet’ Russia (The Washington Times, Aug. 19, 2008)