The Puzzling Story of Manuel Rocha, U.S. Diplomat and Secret Agent for Cuba

What motivated this U.S. ambassador to betray his own country during his decades in the Foreign Service?

BY DAVID C. ADAMS

Manuel Rocha sent this photo to former CIA officer Fulton Armstrong in November 2016 with a note: “In Havana last Thursday.”

Courtesy of Fulton Armstrong

Some diplomats would consider an early career posting to U.S. Consulate General Florence a stroke of good fortune, if not necessarily the fast track to ambassadorship. But when second-tour Foreign Service Officer Manuel Rocha arrived in 1985 to the capital of Tuscany, home to some of the masterpieces of Renaissance art and architecture, his marriage was floundering, and he languished. So when the U.S. ambassador to Honduras, Everett “Ted” Briggs, asked him to move to Tegucigalpa, he jumped at the chance.

Rocha’s decision to abandon Italy for Central America is just one piece of the puzzle confronting investigators as they assess the damage he caused to U.S. interests by betraying his country to work as a secret agent for communist Cuba.

Rocha was sentenced to 15 years in jail in April 2024 after he pleaded guilty to conspiring to defraud the United States and acting as an agent of a foreign country for decades while serving in the State Department.

A Career in Latin America

Rocha spent almost his entire career in Latin America, rising to be ambassador in Bolivia after assignments in Argentina, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Cuba, and Honduras. While he had opportunities throughout his career to provide Cuba with valuable intelligence, the two years he spent in Honduras from early 1987 to early 1989 were potentially among the most rewarding to his spy-handlers in Havana.

Rocha was still a junior diplomat with barely six years of service under his belt when he was handpicked by Ambassador Briggs as political-military officer during a crucial period in the covert, U.S.-funded “Contra” war against the Soviet-backed Sandinista government in Nicaragua. U.S. military and economic aid to Honduras to back its struggle against the Sandinistas saw the U.S. embassy in tiny Tegucigalpa mushroom into one of the largest in the world, packed with aid workers, military trainers, and CIA officers.

Rocha pleaded guilty to conspiring to defraud the United States and acting as an agent of a foreign country for decades while serving in the State Department.

In his memoir, Honor to State, Briggs recalls that he got to know Rocha while serving in the Bureau of Inter-American Affairs, later renamed the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs. “I got to know Manuel as a private citizen who was interested in what we were up to. He had my confidence. I have to wonder if he was playing me,” Briggs said.

Rocha was one of several Spanish-speaking officers Briggs had specifically asked for, along with John Penfold, his deputy chief of mission, and Tim Brown, the officer assigned to handling the Nicaraguan Resistance, the official name of the rebel Contra army. Rocha’s post put him at the heart of sensitive embassy work, including security assistance and access to Honduran military bases for logistics and training of the Contra army. It was in Honduras that Rocha began to build his reputation—or “legend” in spy terminology—as a conservative Cold War warrior.

From Harlem to Yale

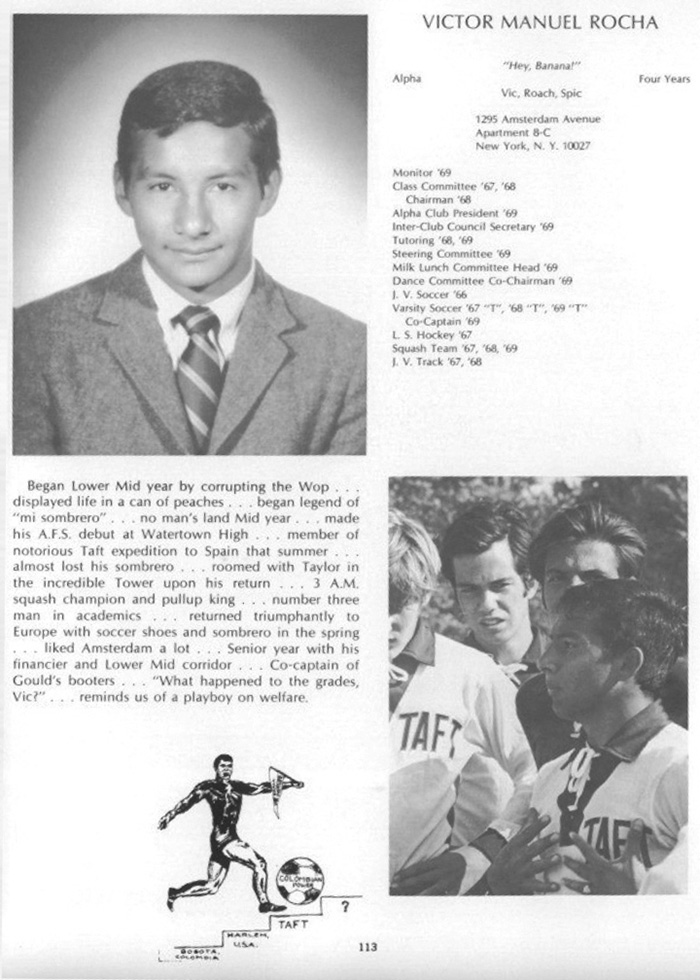

Manuel Rocha’s yearbook photo from Taft, an elite boarding school in Connecticut.

Courtesy of David Adams

That contrasted with his younger days at Yale as a left-leaning student who spent a summer program in 1973 in Chile, where he was allegedly recruited by Cuban agents, according to court documents. A rare, brown-skinned Hispanic recruit in the State Department, Rocha was born in Colombia and moved at a young age to the U.S., where he was raised in Harlem by his single mother, who worked as a seamstress. He won a scholarship to Taft, the elite private boarding school in Connecticut. There, he encountered racism, he later told the Taft school bulletin.

Rocha went on to study at Yale, Harvard, and Georgetown, but never gave any outward signs of resentment toward his privileged white American colleagues. If that were his motive for becoming a Cuban agent, he masked his loyalties well. And if he harbored any left-wing sympathies, he hid that too.

He was briefly married in college to an older Colombian woman, whose identity and possible role in his recruitment remains a mystery. During his PhD studies at Georgetown, Rocha had an internship at the liberal Inter-American Foundation (IAF), a congressionally funded alternative development organization. It was there he met his second wife, Deborah McCarthy, and they joined the Foreign Service together, Rocha via a special expedited program to recruit those from racial and ethnic minority groups.

Rocha’s first job was Honduras desk officer in the office for Central American affairs, where he is remembered as a lively and entertaining colleague who revealed little about his personal life and was highly attentive to his superiors. When the then-ambassador to Honduras, John Negroponte, was doing the rounds in Washington, Rocha was his dutiful assistant, helping arrange his schedule. Rather than be intimidated by Negroponte, one of the department’s leading conservatives, Rocha threw a party for him at his modest apartment in Arlington.

“I could never understand how a junior officer could do that. I was just like, wow! But he pulled it off. I wonder now if he was being pushed by the Cubans,” said Peter Romero, the desk officer for El Salvador at the time.

Negroponte was impressed by Rocha’s pluck but also wondered where it came from. “I always thought he was a bit of an odd duck,” Negroponte told the Journal. “He had that Rodney Dangerfield syndrome—I don’t get no respect.” He was a weak writer in English but made up for it with strong social and analytical skills, developing useful local contacts and delivering valuable information to his bosses, according to several former colleagues.

Rocha was transferred to Florence to join his wife, who was assigned as the financial economist at the U.S. embassy in Rome. He struggled in Florence, and his previously arranged transfer to Rome came under doubt. He was also unfaithful and drinking heavily, former colleagues say. He then got the call to go to Honduras. His move to Tegucigalpa ended the marriage.

The “Contra” War at a Turning Point

Manuel Rocha at breakfast in July 2023, a few months before his arrest.

Courtesy of David Adams

Honduras was a treasure trove of U.S. secrets. In 1986 covert White House funding for the Contras erupted in a major scandal for the Reagan administration. There was also a scandal over CIA ties to the Intelligence Battalion 3-16, a Honduran army unit accused of political assassinations and torture of political opponents.

By the time Rocha arrived, the Contra war had shifted from covert to overt, with $100 million in congressional funding. In 1987 U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz ordered the creation of the Special Liaison Office (SLO), a unique embassy unit formed to keep a close eye on the Contras. Because of the sensitivity of its work, it was walled off from the rest of the embassy, according to David Lindwall, one of two officers in the SLO. “This upset a lot of officers in the traditional political section who were not even allowed to read our cables,” said Lindwall. “That said, Manny Rocha never hit me up for info on the Contras. He was about the only political officer who didn’t,” he added.

It is possible Rocha had other means of access. While not directly involved in the Contra effort, Rocha was intimately involved in delicate negotiations with the Honduran government, including secret access to military bases where logistics for the Contras were being handled, including the supply of surface-to-air “Red Eye” missiles. The Red Eyes changed the course of the war by grounding Nicaragua’s fleet of Soviet Mi-24 helicopter gunships, helping push the Sandinistas to the negotiating table in 1987 and leading to the end of the war.

Rocha also participated in some important meetings with top Contra officials and the Honduran military, according to Colonel Rene Fonseca, a retired Honduran military officer who was the political liaison for the armed forces. “He was very attentive to every piece of information the Contras put on the table to the Americans. He never spoke, he was always taking notes,” Fonseca said. “He sat at the end of the table with a spiral notebook.”

Fonseca recalls three of four meetings with top Honduran military intelligence officers and senior Contra leaders. “They would show maps where their forces were located and go over the results of operations,” he said. “Now, I wonder if that information was being passed to the Sandinistas,” he added.

Briggs doesn’t recall attending Contra meetings with Rocha. “He may have escorted a number of congressional delegations to the Contra camps. But he would not have had access to rarefied intelligence with the Contras,” he said.

Fonseca also socialized privately with Rocha. “He was very reserved, circumspect about some things, but he could be very outgoing too,” said Fonseca. “He would invite me to his house. I imagine he hoped he would get good information from me.”

Manual Rocha and his third wife in an undated photo from Instagram.

Privy to Insider Information

Rocha would have been privy to the regular flow of insider embassy information of value to Cuba’s friends. The embassy comprised a large military group, with a presence outside the capital at the Palmerola Air Base. The U.S. military also used a smaller, more secret base, El Aguacate, to train and supply the Contras.

The CIA had two stations in Tegucigalpa, one standard team inside the embassy and another paramilitary team at a separate location in the capital, known as “The Base,” that was dedicated to the Contra effort. “It was very easy for him [Rocha] to move around in that big embassy. He didn’t have to schmooze in dark bars or call attention to himself. It was a cesspool of good and bad information,” said Fulton Armstrong, a former CIA officer and Central America analyst who knew Rocha. “Maybe his primary function for his handlers was to sort out which was good and bad,” he added.

A rare, brown-skinned Hispanic recruit in the State Department, Rocha was born in Colombia and moved at a young age to the U.S., where he was raised in Harlem by his single mother, who worked as a seamstress.

This author spoke to three exiled former Cuban agents who said that any information Rocha supplied his handlers certainly made its way into the hands of the Sandinistas. After the Sandinista revolution in 1979, Nicaragua’s General Directorate of State Security (DGSE) hired a group of Cuban intelligence officers under Andrés Barahona, a legendary colonel in Cuba’s Ministry of Interior. Barahona was given a Nicaraguan identity, Renan Montero, and placed in charge of foreign intelligence activities, according to Enrique García Díaz, a former Cuban intelligence officer who defected in 1989. “The Cubans controlled everything,” said García.

While Cuban agents handled classified information they suspected came from sources inside the U.S. government, Rocha’s identity would have been a closely held secret, said Jose Cohen, a cryptology expert who worked in Cuban intelligence until he defected on a raft in 1994. “I could tell there were people working in the U.S. government with access to very sensitive information. But I didn’t handle cases. It was very compartmentalized,” he said.

It’s unknown how Rocha delivered information to his Cuban handler. Sending coded messages on shortwave radio to arrange drop-off times and places was one method the Cubans used in other cases, according to retired FBI Agent Peter Lapp, author of Queen of Cuba, about a Pentagon intelligence analyst, Ana Belen Montes, who evaded capture for 17 years.

A Personality Change in Honduras?

An image contained in an affidavit in support of the criminal complaint filed by the Justice Department shows Manuel Rocha meeting with an undercover FBI agent.

Justice Department via AP, File

Some who knew Rocha noticed a change in personality in Honduras. “He became very hard-nosed,” said Maria Otero, who knew Rocha at IAF and ran into him again in Honduras after she was posted there for a microfinance organization. Otero, who later joined the State Department, recalls how Rocha unexpectedly knocked on her door in Tegucigalpa late one night wearing a beige trench coat. She was at home planning how to quietly leave the country with three small children after her husband, Joe Eldridge, a Methodist human rights advocate, had offended the Honduran military chief by penning an op-ed linking him to drug trafficking.

Instead of offering his sympathy, Otero recounts, Rocha told her, “How stupid can your husband be? Doesn’t he know they murder people in this country for that sort of thing?” To her dismay, he added: “If you need help with all this, don’t call me, don’t reach out to me.”

Some embassy colleagues found Rocha arrogant but good company. Lindwall recalled Rocha as “aloof and a fancy dresser—carefully tailored suits, a handkerchief sticking out of his suit coat pockets, expensive ties, cuff links. I thought it was a bit over the top for Honduras, but most of us chalked it up to his being a ladies’ man.”

Others recall him as ambitious and eager to advance his career. “I just thought he was an aggressive climber. And I didn’t trust him, but not because I thought he was working for anybody else,” said John Penfold, the embassy’s deputy chief of mission.

Negroponte was impressed by Rocha’s pluck but also wondered where it came from. “I always thought he was a bit of an odd duck,” Negroponte told the Journal.

Briggs recalls Rocha coming to see him one day on a personal matter. He told Briggs his marriage was ending. “He got all teary and very emotional. It was affecting his work, and he was miserable,” said Briggs.

“I bucked him up and told him, ‘You are a great officer, you’ve got to get over this, and we’ll give you some slack,’” the ambassador said.

A Swift Kick to the Gut

When Rocha was departing post, Briggs hosted a farewell party for him in the Front Office. “Briggs was not one to lavish praise on anyone, but he talked about Rocha as if he was the embodiment of every virtue and skill a young diplomat could ever hope to aspire to,” Lindwall recalled. “I had never heard an ambassador speak so effusively of a staff member. I took it for granted that Rocha must have been one of the best of the best,” he added.

News of Rocha’s December 2023 arrest spread quickly among his old colleagues. “We all feel like we have received a swift kick to the gut,” Amb. Briggs told this reporter. “My colleagues and I have racked our brains about what he did,” he said, adding, “Manuel was the antithesis of a Cuban revolutionary.”

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Unmaking Cuba Policy—The Clinton Years” by Richard a Nuccio, The Foreign Service Journal, October 1998

- “A Blemished Latin American Record” by Larry Birns and Jessica Leight, The Foreign Service Journal, February 2005

- “Former US ambassador sentenced to 15 years in prison for serving as secret agent for Cuba” by Gisela Salomon and Jim Mustian, Associated Press, April 2024