Poznan 1995: Requiem for a Diplomatic Post

The “new American way of diplomacy” following the Cold War saw the closure of provincial posts around the world.

BY DICK VIRDEN

This sunlit building housed the U.S. consulate general and associated United States Information Service (USIS) branch post in Poznan from 1959 until 1995.

Courtesy of Urszula Dziuba

In the mid-1990s, I was serving as the country public affairs officer at U.S. Embassy Warsaw when officials above my pay grade decided to close our consulate general and associated United States Information Service (USIS) branch post in Poznan. The United States had won the Cold War and deserved a peace dividend, the thinking went. We could do without a presence in western Poland. Keeping our consulate general in Krakow, in the south, would be sufficient representation outside the Polish capital.

From my perspective at the time, the decision seemed penny-wise and pound-foolish. It doesn’t look any better today, given Poland’s role as a pivotal frontline NATO state in the struggle to protect Eastern Europe from Moscow’s push to restore its empire. The United States now has 10,000 troops stationed in the country, but we have diplomatic posts only in Warsaw and Krakow.

For decades, we have been closing provincial posts in favor of operating from heavily fortified embassy chanceries. No doubt this new American way of diplomacy is safer and less costly. But it also risks leaving us out of touch with daily life in places like Poland, the Arab street, or in outlying cities, towns, and villages elsewhere around the globe.

Nor does it help advance our foreign policy goals that the agency charged with leading the effort to understand, inform, and influence foreign publics has disappeared into the Department of State, which has other goals. The country founded out of a decent respect for the opinions of humankind apparently decided what others think is no longer a priority.

Edward R. Murrow, the legendary broadcaster (and former U.S. Information Agency director) famously said that in communication, it’s the final three feet that count. Personal contact remains vital today, even with the advent of social media. It’s one reason why posts like USIS Poznan had so much to offer: they were closer to the people.

As Americans once again rethink our country’s role in the world, some even question the wisdom of backing friends and allies such as Ukraine. As we reevaluate, however, we should consider not only what our efforts cost but also what they’re worth.

What follows is my report at the time—written for USIA World, the agency’s house organ—about the value of USIS Poznan, and what was lost when this post and others like it were shuttered.

At the USIS Poznan closing ceremony on Dec. 1, 1995, from left, Ambassador Nicolas Rey, Mrs. Louisa Rey, and Urszula Dziuba, who would become the consular agent, listen to Poznan Consul General Janet Weber. At right front is Dr. Wlodzimierz Lecki, the governor of Wielkopolska from 1990 to 1997; the late Wojciech Szczesny Kaczmarek, mayor of Poznan from 1990 to 1998; and Poznan University Professor Jadwiga Rotnicka, who was the president of Poznan City Council from 1991 to 1998.

Romuald Swiatkowski / Glos Wielkopolski

USIS Poznan Closes, Leaves Proud Legacy

[A Report by Dick Virden, 1995]

On the Poznan-Warsaw train, Dec. 1, 1995—We closed the U.S. Information Service in Poznan today. A small band of Polish civic leaders and American officials did the honors on a cold, sunny morning in the courtyard of the building that has housed USIS, and the consulate of which it was part, since 1959.

There were fine speeches by the ambassador, governor, mayor, and consul general. The mayor said the Americans had always been there since he was a boy; he hoped they might come back one day, not because the difficult times of the past had returned, but for just the opposite reason. He had in mind a Polish economic boom that would make Americans see value in being on the spot.

Speaking for the 25 employees of the consulate and USIS, Public Affairs Specialist Urszula Dziuba talked with dignity and eloquence about the pride Poles took in representing both America and their fatherland, in going to work every day in an office where values like integrity, fairness, and mutual respect were honored.

Poles share America’s passion for freedom, Ms. Dziuba observed, “the more so since it was present in our daily work.” The paradox, she added, is that “it is freedom that is now taking the Americans away from us.”

When the speaking was done, a memorial plaque was unveiled. It reads, in Polish, as follows: “This building in the years 1959 to 1995 proudly served as the headquarters of the consulate general of the United States of America. In the most difficult years of the Polish nation, the consulate was a living symbol of the engagement of America in the return of freedom and independence to Poland. A grateful nation and government of the United States of America dedicates this plaque to the Polish employees of the consulate, who throughout those years faithfully served the cause of Polish-American friendship.”

The craftsman who chiseled the handsome plaque, Mr. Eugeniusz Holderny, refused to accept any payment for his work, saying it was his contribution to the Americans, who had liberated his father from Buchenwald.

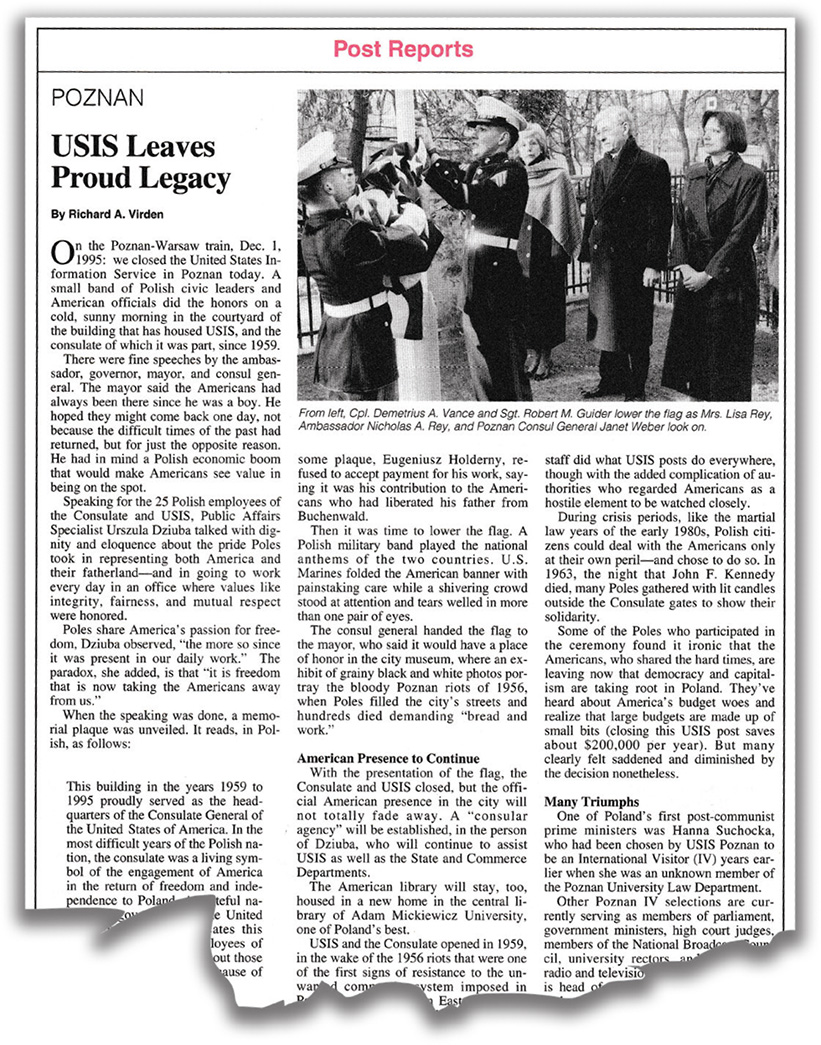

Marine Guards Cpl. Demetrius A. Vance (left) and Sgt. Robert M. Guider lower the flag at the closing of USIS Poznan. Ambassador and Mrs. Rey and Consul General Weber look on.

Romuald Swiatkowski / Glos Wielkopolski

The first edition of USIA World in 1996 contained the author’s report on the closing of USIS Poznan.

Courtesy of Urszula Dziuba

Then it was time to lower the flag. A Polish military band played the national anthems of the two countries. U.S. Marines folded the American banner with painstaking care while a shivering crowd stood at attention and tears welled in more than one pair of eyes.

The consul general handed the flag to the mayor, who said it would have a place of honor in the city museum, where an exhibit of grainy black and white photos portray the bloody Poznan riots of 1956, when Poles filled the city’s streets and hundreds died demanding “bread and work.”

With the presentation of the flag, the consulate and USIS closed, but the official American presence in the city will not totally fade away. A “consular agency” will be established in the person of Ms. Dziuba, who will continue to assist USIS, as well as the State and Commerce departments.

The American library will stay, too, housed in a new home in the central library of Adam Mickiewicz University, one of Poland’s best.

USIS and the consulate opened in 1959, in the wake of those 1956 riots that were one of the first signs of resistance to the unwanted communist system imposed on Poland and elsewhere in Eastern Europe, as the region was then called.

For the next three decades, the USIS staff did what USIS posts do everywhere, though with the added complication of authorities who regarded Americans as a hostile element to be watched closely. During crisis periods, like the martial law years of the early 1980s, Polish citizens could deal with the Americans only at their own peril—and they chose to do so. In 1963, the night John F. Kennedy died, many gathered with lit candles outside the consulate gates to show their solidarity.

Some of the Poles who participated in today’s ceremony found it ironic that the Americans, who shared the hard times, are leaving now that democracy and capitalism are taking root in Poland. They’ve learned about America’s budget woes and realize that large budgets are made up of small bits (closing this USIS post saves about $200,000 per year). But many clearly felt saddened and diminished by the decision, nonetheless.

One of Poland’s first post-communist prime ministers was Hanna Suchocka, who had been chosen by USIS Poznan to be an international visitor (IV) years earlier when she was an unknown member of the Poznan University law department.

Other Poznan IV selections are currently serving as members of Parliament, government ministers, high court judges, members of the National Broadcast Council, university rectors, and directors of radio and television stations. One alumnus is head of the National Bar Association, and another has just published an encyclopedia of American film. Field posts have always been better than embassies at spotting talent at an early age, and Poznan excelled at it.

One reason why posts like USIS Poznan had so much to offer: they were closer to the people.

USIS Poznan can claim many other triumphs: the creation of strong bonds between American universities and Polish counterparts in Poznan, Wroclaw, Torun (birthplace of Copernicus), and elsewhere in western Poland. Visits by jazz greats from Dave Brubeck to Wynton Marsalis and many other cultural presentations belied regime claims that America was a decadent, dying civilization.

When the first NATO exercise ever on the soil of the former Warsaw Pact was held a few miles outside Poznan in 1994, the 600 or so journalists who parachuted in for the occasion managed largely because USIS Poznan staffers were around to help them and military press officers find everything from telephones to the parade ground.

The behind-the-scenes work that made “operation cooperative bridge” a public affairs success was typical of the low-key effectiveness of USIS Poznan, which began as an outpost of the Cold War but went beyond conflict to form friendships, deepen understanding, and sustain the love of democracy, freedom, and independence that eventually prevailed in Poland.

Whatever the future of American relations with western Poland, those who served with USIS in Poznan—among them, Urszula Dziuba, Janusz Buszynski, Irena Horbowa, Roman Jankowski, Barbara Torlinska, Slawak Woch, Jawiga Chojnacka, Czeslaw Jankowiak, Len Baldyga, Jack Harrod, Larry Plotkin, John Scott Williams, Patrick Hodai, Richard Lundberg, Doug Ebner, Janet Demiray, Daniel Spikes, Sharon Lynch, Thomas Carmichael—know their work there mattered.

USIS Poznan leaves a legacy to cherish.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Keeping a Dream Alive” by Dick Virden, The Foreign Service Journal, June 1999

- “The State of Democracy in Europe and Eurasia: Four Challenges” by David J. Kramer, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2018

- “Prying Open a Closed Society in Poland” by Dick Virden, The Foreign Service Journal, September 2024