The State of Democracy in Europe and Eurasia: Four Challenges

In a decade of backsliding on democracy around the world, the countries of Europe and Eurasia feature prominently.

BY DAVID J. KRAMER

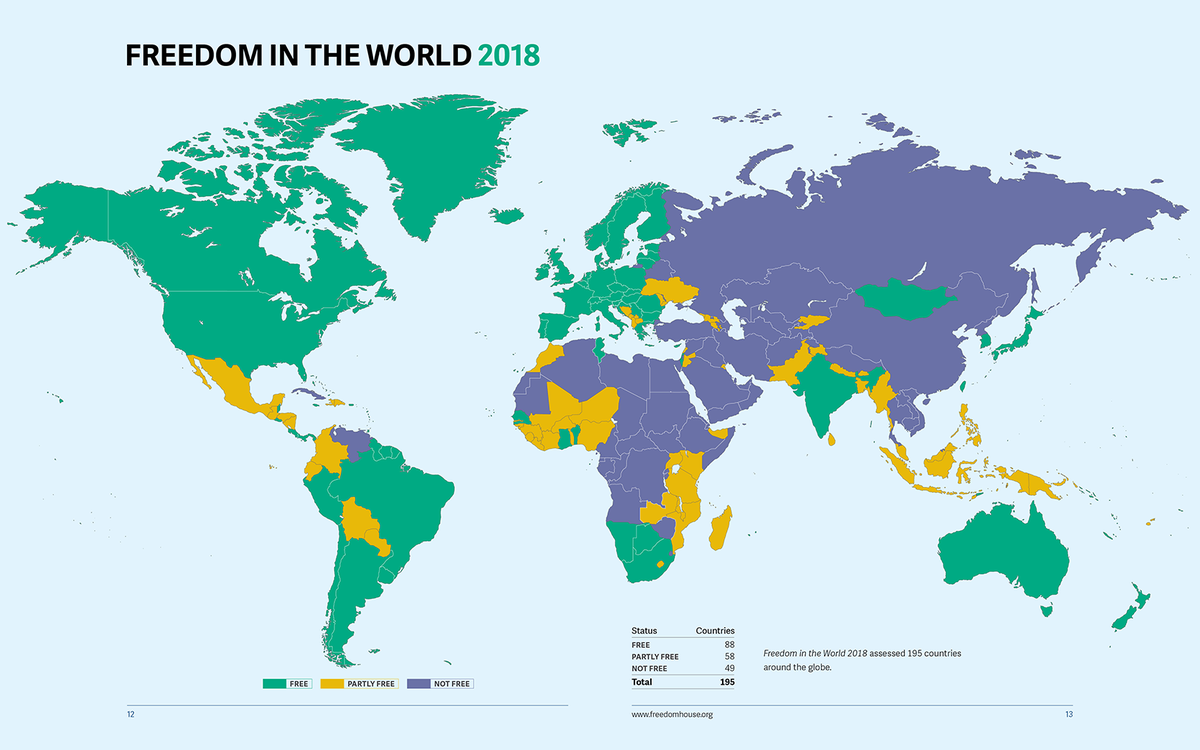

Courtesy of Freedom House

In its most recent annual survey, “Freedom in the World 2018: Democracy in Crisis,” Freedom House documents 12 straight years of decline in political rights and civil liberties around the world. The countries in the Europe and Eurasia region play a significant role in this overall decline.

Indeed, the region is beset with four major challenges to democracy, all interrelated: the authoritarian challenge posed especially by Vladimir Putin’s Russia; the backsliding from democracy in countries such as Hungary, Poland and Turkey; a general lack of confidence in the democratic system among countries on the continent; and corruption, which opens the door for nefarious forces to undermine democratic, market forces.

The confluence of these four factors has put Europe in a dangerous position.

The Authoritarian Challenge

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s authoritarian regime leads the campaign to undermine the very concept of democracy in Europe, the United States and other countries in the Western Hemisphere. We saw this with Russia’s interference in the U.S. election in 2016 and elections in France, Germany, Austria and the referendum in the Netherlands; we are seeing it with Russian interference in Mexico’s presidential election scheduled for this July.

The Kremlin uses bots and trolls in an online effort to tap into divisive, sensitive topics such as immigration and to spike debate with phony tweets and messages. For example, in January 2016 they spread a false story in Germany about a Russian-German girl who was allegedly raped by illegal immigrants. For nearly a decade, RT and Sputnik, the Kremlin’s main propaganda outlets, have been used not to promote and elevate the image of Russia, but instead to denigrate democracies in Europe and the United States, claiming that these countries are corrupt and unresponsive to voters’ concerns on issues such as immigration.

Putin views democracies on the continent, especially those that border Russia, as a threat to the system he has in place. He especially regards popular movements by Ukrainians, Georgians and others pressing for integration with the Euro-Atlantic community, greater democracy and an end to corruption as a serious challenge to the political model he has established in Russia, which depends on perpetuating the myth that the West and the United States are threats. Putin refuses to accept that people in Ukraine and Georgia, for example, to say nothing of Russians themselves, are capable on their own of demanding better from their leaders; they must be instigated from outside. This is why he accused former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton of giving a “signal” to Russians who protested the fraudulent parliamentary elections in December 2011.

But Putin is not alone in leading the authoritarian charge. Ilham Aliyev oversees a massively corrupt regime in Azerbaijan, which has more political prisoners than Russia. Belarus continues to suffer under Aleksandr Lukashenko’s tight grip on power. The United States has applied targeted sanctions for human rights abuses against Putin’s Russia and Lukashenko’s Belarus, but not against Aliyev’s Azerbaijan. Leaders of all these countries need to know that there are consequences for engaging in gross abuses against freedom, targeting critics and denying the opposition the right to participate in the political process, as well as for interfering in other countries’ elections. Western democracies should not legitimize phony elections in Russia (in March) and Azerbaijan (April), and Western leaders should not be congratulating these leaders for winning rigged elections.

It is important to remember that the way regimes treat their own people is often indicative of how they will behave in foreign policy. If they engage in authoritarian practices within their own borders, they are less likely to respect the rights of people elsewhere, to say nothing of concepts of sovereignty and territorial integrity (see Russia’s invasions of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014). If we do nothing in the face of gross human rights abuses, we signal to leaders in these countries that they can get away with such behavior, emboldening them to push the envelope even further. For the sake of freedom and democracy, as well as for security reasons, it is important to push back against authoritarian behavior in Europe and elsewhere.

Democratic Backsliding in Europe

Poland and Hungary were among the first in Europe to transition from communist systems to thriving democracies. Their membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union was the culmination of their efforts to return to the European fold. Poland has been a leader and model for other countries in the region seeking to make a similar change. Following the victory of the Law and Justice Party in Poland in 2015, however, the European Union and human rights groups have raised concerns involving the courts and justice system, press freedom, nongovernmental organizations and treatment of the previous party in power. They have voiced similar concerns regarding Viktor Orban and his Fidesz Party in Hungary.

As Freedom House notes in its 2018 survey, “In Hungary and Poland, populist leaders continued to consolidate power by uprooting democratic institutions and intimidating critics in civil society.” While Poland remains strongly suspicious of Putin, Orban has been much more receptive to returning to “business as usual” with Russia, threatening to undermine European unity in confronting the Putin challenge. That said, both countries joined with the United Kingdom, the United States and others in expelling Russian diplomats in March for the Kremlin’s alleged role in the poisoning of a former Russian spy and his daughter in the U.K.

Turkey is another country going in the wrong direction; Freedom House moved it from the “partly free” to the “not free” category in this year’s survey, the “culmination of a long and accelerating slide” in that country, according to the human rights organization. Since a coup attempt in 2016, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has arrested tens of thousands and fired many more from various government and other jobs. More journalists are in prison in Turkey—roughly 150, many accused of support for the Gulenist movement—than in any other country in the world.

Brexit demonstrates how Europe lost confidence in the path it was on—toward greater integration, solidifying of democratic gains and a market system.

According to the Freedom House survey, “In addition to its dire consequences for detained Turkish citizens, shuttered media outlets and seized businesses, the chaotic purge has become intertwined with an offensive against the Kurdish minority, which in turn has fueled Turkey’s diplomatic and military interventions in neighboring Syria and Iraq.” That has created problems for the United States and the forces it backs in Syria and Iraq. Again, the way Erdogan treats his own people reflects the way he aggressively and dangerously goes after forces he doesn’t like beyond Turkey’s borders.

Beyond these three countries, right-wing populists and nationalists are winning seats in various European parliamentary elections, as well as in the European Parliament. They denigrate democratic values, demonize immigrants and refugees, and play into the hands of Putin by threatening the sustainability of the democratic model. The fact that far-right leader Marine Le Pen made it into a runoff election against Emmanuel Macron is frightening, even if Macron ultimately won. The rise of the Alternative for Germany Party, the first far-right party to win representation in Germany’s Bundestag since 1945, should be additional cause for concern. The victory of the Five Star Movement and the League in Italy’s elections made Putin happy but has pro-E.U. and pro-democracy forces deeply concerned. The United Kingdom has long been one of the continent’s leaders in defending and promoting democracy, but Brexit has reduced its profile considerably in this area, and in the European Union more broadly.

A Lack of Confidence

Brexit demonstrates how Europe lost confidence in the path it was on—toward greater integration, solidifying of democratic gains and a market system. Negotiations between London and Brussels have damaged the union’s standing and energized other countries, such as Poland, to defy Brussels. Splits within the E.U. cause it to lose its appeal among aspiring nations like Ukraine and Georgia, as well as countries in the western Balkans. The desire to join the organization has long been an incentive for nations to undertake difficult reforms to meet the criteria for membership. If the image of the E.U. suggests confusion and disenchantment, aspiring states might rethink their goals and, in turn, abandon important but difficult democratic and economic reforms. That would be a further setback to the cause of democracy on the continent.

Equally important, the European Union seems uncertain how best to fight the authoritarian challenge. In contrast to the strong sanctions imposed after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, only four states—the United Kingdom, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania—have imposed sanctions for Russia’s gross human rights abuses. Failure to enact measures like those the United States has in place under the 2016 Global Magnitsky Act (the Russia-specific Magnitsky Act passed in 2012) signals Europe’s weakness to Moscow. Similarly, the E.U. seems feckless in the face of backsliding among member-states like Poland and Hungary. And the only reaction to Erdogan’s crackdown in Turkey has been to delay further talks on possible membership, a goal many in Turkey have already given up.

Leaders on the continent have become too removed from the needs of their voters, and the refugee crisis of 2015-2016 exacerbated the rise of xenophobic forces there. The need to pay more attention to constituents should not translate into doubts about the democratic system of government, however. Europeans should remember the words of Winston Churchill: “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.” Failure to defend their democracies plays right into the hands of Putin.

Corruption

Putin also exploits European weakness through corruption, his greatest export. But for Putin to export corruption, the West, including the United States, must agree to import it. That Marine Le Pen’s party openly took roughly $10 million from a Russian bank for the campaign last year should be a source of shame, not pride. Moreover, it should be illegal to accept foreign funds, as it is in the United States. Making foreign funding of elections, parties and candidates illegal would go a long way toward limiting Putin’s corrupting influence.

Transparency in funding for think-tanks and research institutes is also necessary to ensure they are not fronts for the Kremlin, their cronies or others like the Aliyev regime. There should also be greater transparency in high-end purchases of real estate, companies and other assets. The derisive nickname “Londongrad” refers to the Russian, Azerbaijani and other money, much of it ill-gotten, flowing through London’s banks and real estate market. Going after corrupt Russian and other money should be a top priority for Western governments.

Continued dependence on Russia for energy also contributes to corruption in Europe. Putin uses oil and gas as tools against others, and projects like Nord Stream II, a pipeline that would run from Russia to Germany under the Baltic Sea, should be viewed through this lens. This pipeline would eliminate Ukraine as a transit country, causing serious harm to that country’s economy. Moreover, the pipeline is not commercially viable, since Nord Stream I, along which Nord Stream II would run, is not near full capacity. It instead would entrench German-Russian energy ties at a time when such reliance is prone to manipulation and pressure from the Kremlin.

Ukraine’s past dependence on Russian energy left it vulnerable when Moscow decided to turn off the taps to Ukraine in the height of winter. The energy sector in Ukraine has been thoroughly corrupt for years, but the reduction of Ukraine’s reliance on Russian supplies for its own domestic consumption and development of alternative energy sources, along with an end to wasteful subsidies for heating, have helped Ukraine address this vulnerability. Still, Ukrainians worry that the tremendous sacrifices they made during and since the Euro-Maidan Revolution in early 2014 are being forgotten amid massive corruption that threatens their country’s future as much as Russia’s military aggression does.

To be sure, even without Russian influence, the West has had corruption problems; but Putin makes the problems significantly worse. Working together, Europe and the United States need to clean up their own house and deprive Putin of openings to exploit. They should impose sanctions, as permitted under the Global Magnitsky Act, for corruption originating from places like Russia and Azerbaijan. If those who engage in illicit activities cannot enjoy the fruits of their ill-gotten gains, they might be less likely to engage in such activity in the first place.

What to Do?

If current trends continue, we will see weakened democracy across the continent, an emboldened Putin and increased corruption—a dire outlook. Questions these days about the United States’ commitment to democracy do not help. European governments need to aggressively defend and promote democracy and freedom throughout the continent. They must not assume that countries that seem to have made the transition to democracy successfully are finished with their work.

We in the West must restore confidence that democracy, while not perfect, is the best system of government we have. We must push back against the authoritarian challenge and recognize Putin for the threat that he is. We should pass and enforce legislation and sanctions policies that put authoritarian leaders and their accomplices on the defense. It is time, in other words, for Europe and the United States to seize the initiative, securing gains and victories for democracy and freedom on the scoreboard.