From “Redneck Hillbilly” to “Radical” to Career Diplomat

Reflections

BY JAMES R. BULLINGTON

Freedom Riders sit in front of their bus that was destroyed by a white mob, 1961. These men and women were attempting to integrate public transportation facilities by riding buses across the South, a movement that spurred the author to action that year.

Everett Collection Inc / Alamy

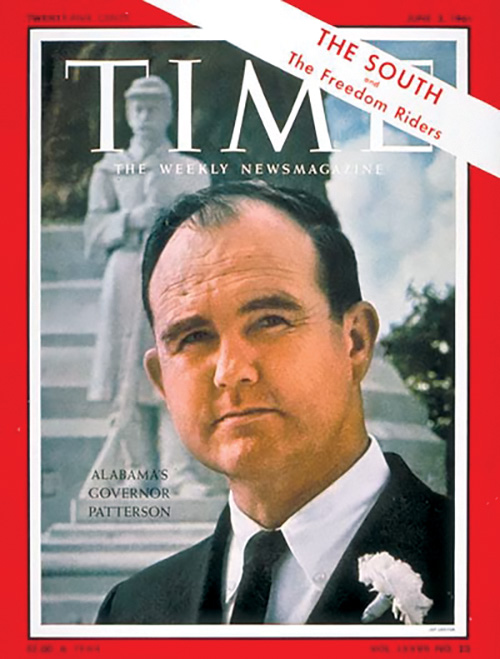

Governor John Patterson on the cover of Time magazine, June 2, 1961. The diagonal banner references the Freedom Riders.

Time Magazine Archive

My family background is a combination of north Alabama redneck and east Tennessee hillbilly. I grew up on a small cotton farm west of Huntsville and in a working-class neighborhood of Chattanooga, and when I entered Auburn in 1957, I was the first in my family to go to college.

In that culture, and that time, the State Department and the Foreign Service were as unknown as the dark side of the moon. And yet I went directly from being a redneck hillbilly student at Auburn to being a career diplomat.

Now how the hell did that happen?

The governor of Alabama had a significant role in making this transformation possible. To explain, it’s necessary to recall the Foreign Service and the entry process of that era.

When Congress created the Foreign Service in 1924, it instituted a competitive entrance examination, beginning with a nationwide written test similar to the GRE or LSAT. That was followed by an oral exam at the State Department that featured a three-hour grilling by a panel of senior Foreign Service officers.

Plus, academic records, foreign language competency, recommendation letters, and work experience were all taken into consideration. Only about 3 percent of the applicants ended up as FSOs.

Until the 1970s, FSOs were almost always the sons of wealthy elites and professional people; and the overwhelming majority were graduates of Ivy League and other prestigious universities, mostly with advanced degrees and international experience.

Half the members of my entering Foreign Service class graduated from three universities: Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. The rest were alumni of Georgetown, Stanford, Duke, and similar schools.

My university, Auburn, the land-grant university of Alabama, produced primarily farmers and foresters, engineers and schoolteachers, and lots of military officers through one of the country’s largest ROTC programs. It had never produced an FSO. I got the idea of joining the Foreign Service from a Newsweek article.

Consequently, when I came to Washington in 1962 to enter the Foreign Service, I felt seriously out of place among my junior officer classmates. On discovering that the State Department had recently begun an effort to diversify its recruitment base, I concluded that I must have been that year’s token redneck.

In addition to possibly benefiting from some affirmative action, I’m confident that the most important reason for my success was my Freedom Riders editorial and the reaction to it.

I became editor of the Auburn University student newspaper in May 1961, at the time of the Freedom Riders incidents, which involved young people riding Greyhound buses across the South in an attempt to integrate bus terminals. When the Freedom Riders got to Anniston, Montgomery, and Birmingham, they were attacked by white mobs as Alabama state troopers stood by and did nothing. These scenes were featured on national television.

I had always accepted segregation as the natural order of my limited world. At Auburn, it was in full force. No one in my family or among my friends or teachers or preachers questioned the Jim Crow system, and I had not given it much thought.

But as I watched reports about the Freedom Riders incidents and reflected on a newly published book I had just read, To Kill a Mockingbird, I had a civil rights epiphany. In an editorial that I put on the front page of the newspaper, I denounced the mobs that attacked the Freedom Riders and the Alabama political leaders who promoted this violence; rejected the Jim Crow culture in which such actions and attitudes were rooted; and called for the peaceful integration of Auburn University.

The author (left) receives Auburn University’s Lifetime Achievement Award from Auburn Alumni Association President Regenia Sanders in 2022.

Auburn University / Flickr

This doesn’t sound at all radical in 2023, but in Alabama, in 1961, it was downright revolutionary! Reaction to the editorial was swift, beginning with a Ku Klux Klan cross-burning at the Sigma Pi house where I lived. There were also threatening phone calls, and students burned copies of the paper and shouted insults as I walked across campus.

The university president called me an “irresponsible radical” and told me to submit all future editorials to the dean of student affairs.

The next day the story was in newspapers across the state and beyond, even The Washington Post and The New York Times. This prompted Governor John Patterson to get involved.

Patterson had defeated George Wallace in his first run for governor, in 1958, because he was even more extreme than Wallace in his defense of segregation. In his inaugural address, he declared: “I will oppose with every ounce of energy I possess and will use every power at my command to prevent any mixing of white and Negro races in the classrooms of this state.” His campaign against the Freedom Riders earned him a cover story in the June 2, 1961, issue of Time magazine.

Patterson’s response to my editorial was both vigorous and vociferous, including a threat to cut Auburn’s appropriations if something were not done to “throttle that damn radical agitator editor.” The university president told me that I had “really pissed off” the governor.

But the national media attention gained by my editorial and the reactions to it, plus fear of endangering Auburn’s accreditation if they fired or expelled me, caused the university administration to stop short of such drastic action. I refused to accept censorship and continued to publish material opposing segregation for the remainder of my yearlong term as editor, pretty much daring the university administration to remove me.

I passed the Foreign Service written exam in December 1961 and was invited to come to Washington for the oral exam the following April. The examiners were especially interested in hearing my views on civil rights, which gave me the opportunity to tell them the story of the Freedom Riders editorial.

This, I’m convinced, is the only thing that could have sufficiently set me apart from my better educated and more experienced competitors to pass the oral exam and be invited to join the Foreign Service, the youngest member of my class—before I had even graduated from college.

Fast-forward to 1979. The State Department had sent me for a year of training at the Army War College, and my class was about to graduate. For the graduation ceremony, as it did every year, the Army invited prominent citizens from around the country to attend. Among the group that year was none other than John Patterson, former governor of Alabama.

The day before the ceremony, there was a reception for the graduates and distinguished visitors. I recognized Governor Patterson and made my way to him through the crowd. “Governor,” I said, “we’ve never met, but when you were governor of Alabama, I was editor of the student newspaper over there at Auburn.”

He immediately drew back, poked his finger at my chest, and exclaimed: “So you’re the son of a bitch that wrote that editorial!”

I was proud to acknowledge that I had indeed written that editorial. I was delighted that it had bothered him all those 18 years; but I passed up the opportunity to thank him for unwittingly helping me get into the Foreign Service in 1962.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.