Serving at the Panda Post

Reflections

BY DOUG KELLY

A trio of pandas chomp on bamboo at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding in Sichuan, circa 2011.

Chensiyuan

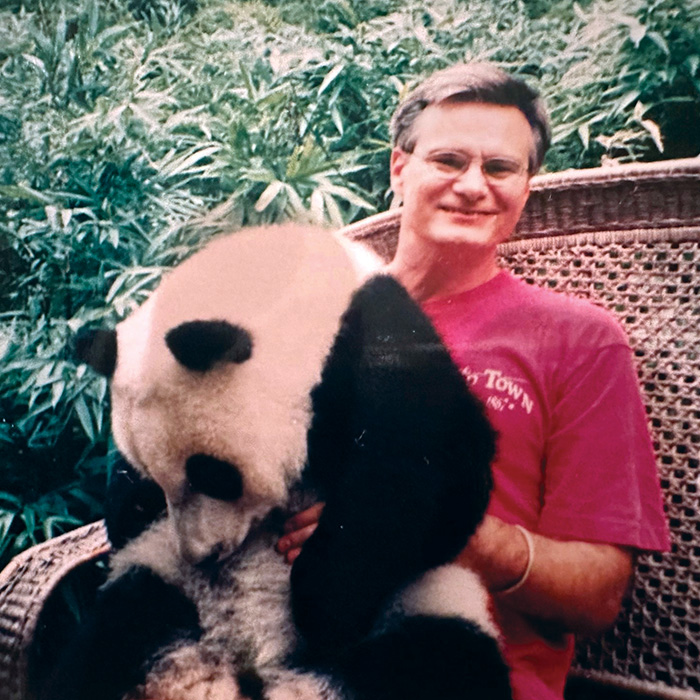

The author with a panda in Wolong National Nature Reserve in Sichuan province in 1998. “The panda looks resigned to the (exciting for me, not for him) photo-op,” notes Kelly.

Courtesy of Doug Kelly

When I took up my assignment as consular chief in Chengdu in 1998, little did I know what I was getting into. Everyone understood that it was the jumping-off point for Tibet and that Tibetans and other minority nationalities lived just a few hours west and south of the city. That was a big reason why I had bid on the post and endured two years of Mandarin at the Foreign Service Institute.

But soon I was made aware of a fact that came to define the post for many: Chengdu was Panda Central. AmConsulate Chengdu spent a considerable amount of time ensuring that official visitors felt satisfied they had taken advantage of their visit to enjoy the Panda Experience.

Whether it was the deputy chief of mission in Beijing, China desk people from State, or congressional staff aides, they all clamored for photos of themselves with one of these cuddly creatures. For those not satisfied with a tame visit to the nearby Chengdu Panda Research Center, that meant taking the visitors on an all-day trip deep into the mountains to the high bamboo forests of the Wolong National Nature Reserve.

All of us at the consulate reveled in Chengdu’s reputation as the home and center of all things panda. We entertained our visitors with panda jokes (A panda walks into a bar …), and the consulate’s monthly newsletter was “The Panda Post.” We even thought of dressing a colleague up in a panda suit and letting him roam the atrium for our guests’ entertainment. He demurred.

What is it about pandas that elicits this response in people? Whatever it is, it is certainly real, and now with the recent decision by China to recall the pandas from American zoos, a certain national “panda withdrawal” is going on among the general public.

The National Zoo’s panda family—Mei Xiang the mom, Tian Tian the dad, and their son, Xiao Qi Ji—flew back to Chengdu in early November of last year.

This news got me thinking of when they first came to America, and the small part I played in their journey.

By way of background, in 1972, during President Richard Nixon’s groundbreaking visit to China, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai announced a gift of a pair of pandas. The pair, Ling Ling and Hsing Hsing, produced five cubs during their time at the National Zoo, but none of them survived more than a few days after birth. When both Ling Ling and Hsing Hsing passed away in the 1990s, there were no pandas left in the zoo.

Panda lovers clamored for new pandas to fill the void. The consulate in Chengdu was ground zero in the search, and we cooperated with local authorities to find a pair to send to the National Zoo. Finally, a pair was selected.

I don’t remember exactly why I was picked to represent the United States at the pandas’ Dec. 6, 2000, farewell at the Chengdu airport. I suspect it was because no one else “volunteered” to get up before dawn on a predictably damp, chilly winter day and listen to a speech wishing the pandas yi lu ping an (“bon voyage” in Mandarin Chinese) while shivering in the unheated departure lounge.

After the speech, I joined Mei Xiang and Tian Tian at the side of the chartered American airliner on the tarmac (their son, Xiao Qi Ji, was only a gleam in their eyes at this time). They were in their cages, about to be hoisted up to the door of the airplane.

All of us at the consulate reveled in Chengdu’s reputation as the home and center of all things panda.

I was told by the airport authorities that it would only be proper for me to accompany them to the plane’s entrance, and as there seemed to be no other way to get up there, I gingerly stepped onto the metal platform supporting the pandas’ cages.

With a jerk and a clang, the platform was hoisted up toward the plane’s door. My charges ignored me as they noisily munched clumps of bamboo, with me a few feet away clinging to a metal rail for balance in full formal diplomat attire.

When we finally reached the door, I looked into the brightly lit, retro-fitted-for-pandas first-class cabin. The smartly dressed, eager American flight attendants were excited to meet their VIP passengers.

I asked one of them about the flight path, and she proudly responded: “Direct nonstop to Washington, D.C.” That seemed incredible to me at the time—nonstop flights for humans between Chengdu and the U.S. didn’t start until 14 years later.

So I said my goodbyes to Mei Xiang and Tian Tian, stepped back onto the unsteady platform, and was lowered back down to the tarmac, little realizing that 23 years later, they would once again become pawns in the game of diplomacy.

In November 2023, there were no Americans to greet the pandas when their flight landed in Chengdu. China had ordered the closure of American Consulate Chengdu in July 2020, after the U.S. ordered the closure of the Chinese consulate in Houston a few days earlier.

There are reasons, however, to be optimistic about the future of pandas in America. At the recent Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting this past November in San Francisco, the Chinese floated the idea of sending a pair of pandas to the San Diego Zoo. Some observers see this as a sign of a thaw in bilateral relations. Can panda diplomacy once again lead to improved relations between the United States and China?

China hands would agree that Chengdu may have been the most fun post in China, and being Panda Central was certainly a big part of that. Eats shoots and leaves, we miss you.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.