A Century of Service: Firsthand Accounts from U.S. Diplomats

Over the 10 decades since the Rogers Act created the modern Foreign Service, America’s diplomats have made extraordinary contributions to advancing our nation’s security, prosperity, and ideals. At posts around the world, practitioners from U.S. foreign affairs agencies have been promoting the national interest in concrete ways, serving our citizens overseas as well as American farmers, businesses, and workers back home. Their service often goes uncelebrated, and so The Foreign Service Journal turns to the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training (ADST) and its Foreign Affairs Oral History Program to help tell their stories.

Drawing from ADST’s collection of more than 2,600 oral histories, these accounts from across a century of service illustrate the breadth of the work individual American diplomats do at home and abroad and the challenges they routinely overcome. Evacuating citizens, controlling immigration, negotiating alliances, promoting trade, protecting farms, preserving jobs, defending health, responding to crises, fostering peace, reuniting families, and sometimes simply living up to the ideal America represents to the rest of the world—the list of their duties is long, their dedication exemplary.

Founded in 1986, ADST is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to promoting understanding of diplomacy and diplomatic practitioners. The core of the association’s work involves capturing and sharing the oral histories of diplomats. ADST’s collection—including compilations focused on particular subjects and countries, as well as the full oral history of each diplomat in this article—is accessible at https://adst.org. In addition, ADST assists in the preparation and publication of books on diplomacy and contributes to case studies and educational materials for both practitioners and students of diplomacy. Its innovative outreach efforts include podcasts, social media, lesson plans for high school teachers, and an online series, “Moments in Diplomatic History,” presenting key international developments and humorous aspects of the Service through the eyes of its practitioners.

This centennial year, ADST is redoubling efforts to collect and amplify firsthand accounts of extraordinary contributions by America’s diplomats through the “Century of Service and Sacrifice” initiative, an effort to bolster public awareness and appreciation of the role diplomacy plays in advancing our national interest. As part of this effort, ADST is spearheading a coalition of foreign affairs associations, including AFSA, in advocating for congressional passage of the United States Foreign Service Commemorative Coin Act (H.R. 3537/S. 789)—bipartisan, budget-neutral legislation directing the Treasury Department to mint a coin commemorating 100 years of the modern U.S. Foreign Service. Proceeds from sale of the coins would go to support ADST’s foreign affairs oral history program. Go to https://adst.org for more information on joining the coin effort or submitting your own story for the “Century of Service and Sacrifice” initiative.

The team at ADST is dedicated to honoring the remarkable accomplishments of America’s diplomats. We hope you enjoy this journey through a century of service.

—Tom Selinger, Executive Director, Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training

Infantry of the Polish Army during the Battle of Warsaw, August 1920.

Wikimedia Commons

1920

Preparing an American Evacuation as Bolsheviks March on Warsaw

In one of the earliest accounts in ADST’s collection, Foreign Service Officer Jay Pierrepont Moffat records in his journal how the tiny U.S. legation in Warsaw coped with an ultimately unsuccessful Soviet push to take over Poland, coordinating with a Polish government under siege, burning documents, and evacuating American citizens. Moffat would later serve as U.S. ambassador to Canada during World War II.

The Bolsheviks were by now at the gates of Grodno. The time had come to make plans for evacuating the American colony. … So far as we knew there were at least a thousand Americans in Warsaw. Most of them were naturalized [U.S.] citizens who had come to Poland for the sole purpose of persuading their relatives to return with them to the United States. They had come, they said, to save these poor unfortunates, and they were not going to leave without them. …

The Polish authorities when approached became exercised at the mere thought of evacuation. The minister of railroads told me that any concerted exit of Americans would produce a panic in Warsaw. … Were we not acting prematurely? Would we not withdraw our request for rolling stock? Under questioning he had to admit that with each day’s delay there would be fewer and fewer railway carriages available.

At last I got a contingent promise of a special train to take the Americans to Danzig [today Gdansk], though the minister made it clear that no luggage or heavy effects could be transported. One freight car would be reserved for the chattels and records of the Legation, but that was the limit of what he could do. I spent a good part of the next day trying to rent some barges to float heavy luggage down the river. …

Our mere presence in Warsaw after the others had left was an encouragement to the Poles, and we felt that American prestige would be enhanced by our remaining until the very last moment. But what was the very last moment?

–Jay Pierrepont Moffat

Nothing could now be seen that was to save Warsaw from its doom. … Jack White [fellow member of the U.S. legation] called in the heads of the various American groups and told them in unmistakable terms that the time had come for the evacuation to begin. Two hundred places were reserved on the Danzig train the following night. But to our chagrin, many declined to go, selfishly declaring that they wished to be the last to leave. …

Meanwhile I went upstairs and started burning documents. For four hours on a summer day I stood before a huge open hearth, feeding papers to the flames, neither too fast nor too slowly, and breaking up the glowing ash with a heavy poker. Let no one who has not done as much belittle that fatigue. …

Jack White and I reviewed our own situation. We had instructions from Washington not to risk capture by the Bolsheviks for fear we might be held as hostages. On the other hand, our mere presence in Warsaw after the others had left was an encouragement to the Poles, and we felt that American prestige would be enhanced by our remaining until the very last moment. But what was the very last moment? And how could we determine it? We finally decided to remain until the Poles blew up the two great bridges crossing the Vistula between Warsaw and its suburb Praga. …

We tried to work, but it was a meaningless shuffling of papers. … It was not until after seven o’clock that we left the Legation. … To our surprise the Great Square was roped off, but lined up within the cordon we could see row upon row of unarmed soldiers, standing sullen and sweating in the August heat. We looked again and sure enough, the uniform they wore was Bolshevik. … A thousand prisoners taken that morning in battle could mean only one thing—a sizable Polish success. …

At the very moment when all seemed lost, there came a transformation in the Polish spirit, born of a realization that if Warsaw fell, there could be no survival for the Polish state, no future for the Polish race. Fired by an idea, the Poles gained an ascendancy in morale and this they retained through the remaining weeks of the war.

1931

Promoting American Trade in Bogotá

Growing up on a ranch in Montana, Aldene Alice Barrington became a teacher in Puerto Rico and then joined the U.S. Commercial Attaché Office in Colombia in 1927. By 1931 she had risen to the rank of assistant trade commissioner, one of the earliest members of what became the Foreign Commercial Service. She tells of preparing Commerce Department reports, compiling information we now know as Country Commercial Guides, and assisting American companies in entering the market—all while quietly breaking professional barriers for women.

In the beginning, I was somewhat unusual. American companies locating there would have loved to have found available English-speaking people to employ for clerical jobs in their offices. I was, more or less, office manager … and we had to do an awful lot of reporting. I started on my own—I was really pushed into it, because everyone was so very busy—reporting on different commodities and opportunities for trade and investments because that was primarily what the Department of Commerce wanted. I can remember getting that department pouch off, which was quite a task, every week. …

I remember one of the reports that I was pushed into writing was about doing business in … not Latin America, but the specific country. And you had to answer a lot of questions about their legal requirements and points of view and what the American company had to do in order to establish itself, pointing out the difficulties and the differences, which most Spanish-speaking countries probably inherited from Spain. The government had control of industry, and certainly of natural resources, and their many minerals, which included petroleum. Such widespread government ownership was foreign to the American point of view, because we didn’t have similar strict controls here. … And one had to explain the differences and difficulties and what the company had to overcome.

Americans, by and large, just took for granted those obstacles they had to overcome or comply with and decide whether it was worthwhile for them to be located there. No, there weren’t any adverse feelings. It was just a matter of taking into account and knowing what you had to do in order to become entrenched in the country.

I realized that, sometimes, with my credentials, I could get into places that women had not been in. I was never refused at all, although maybe some eyebrows were raised.

–Aldene Alice Barrington

There was the Barco concession for oil. Gulf Oil and Standard Oil were already there, and Phillips, with others, all were negotiating to get a slice of the concession. …

There were so many products not locally produced; and as tariffs were not too high, a lot of consumer goods could be imported without difficulty. And, of course, we were trying to increase exports from the U.S. … Our office would put an American exporter in touch with a prospective local representative for their products.

My category was changed to assistant trade commissioner, which is officer status. It was unusual [for a woman], but I never felt it, really. It was just a job to be done, and I never thought of that aspect of it. I realized that, sometimes, with my credentials, I could get into places that women had not been in. I was never refused at all, although maybe some eyebrows were raised. But anyplace I’ve been I have always made friends with the local people and devoted a lot of time to that.

Later, in Brazil, for instance, the things I handled required doing things, and some things I probably didn’t have to do, but I wanted to do, such as going down in the São João del Rei mine. I think it’s one of the deepest gold mines in the world, in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Well, of course I didn’t realize it at the time, but there is a feeling that it’s bad luck if a woman goes down. I … was informed I could go down. Later I realized they were a little bit hesitant about it. But they let me go down that elevator shaft, and it was quite an experience.

1938

Exercising Compassion and Quotas as Jewish Refugees Flood Cuba

In Havana, on April 24, 1948, at least 10 years after Jewish refugees first landed in Cuba, the Community Kitchen Restaurant holds a Refugee Community Seder for Passover, funded by the Joint Distribution Committee and organized by the Federation of Ex-Ghetto and Concentration Camp Prisoners.

JDC Archives

Arriving in Havana, newly minted Vice Consul William Belton walked into a wave of Jewish refugees who had escaped Europe and were waiting to become eligible for U.S. visas. As deputy chief of mission in Brazil 30 years later, Belton would negotiate the release of Ambassador Burke Elbrick after his kidnapping.

Havana was flooded with European refugees. This was just before the outbreak of the war. The city was just full of German Jews who had been unable to get U.S. visas while they were still in Europe; so [they] had come to Havana to wait until their numbers came up on the quota system for the United States. … I never felt there was anything but sympathy for this tremendous problem and the people involved in it. There was a difference between our attitude toward these people, how we handled them, and what the laws enabled us to do for them.

Thousands of people were eventually going to get into the United States, one way or another. We knew that. It was a tragedy that we had to keep them sitting there on the benches in the parks of Havana for years on end sometimes, before they could come. When they walked into the office, we did the very best we could under extremely difficult circumstances. Understandably, the visa applicants themselves weren’t always models of patience.

I remember on one occasion we received a complaint from the United States about how somebody was treated at the reception desk. The consul general, Coert du Bois, was a very imaginative and gung-ho officer. When he got this complaint, he had a photographer come and take a picture of the receptionist at work.

I never felt there was anything but sympathy for this tremendous problem and the people involved in it. There was a difference between our attitude toward these people, how we handled them, and what the laws enabled us to do for them.

–William Belton

It was a very dramatic picture. There was this young woman at her desk surrounded by at least 20 people, all with their arms out, shouting at her, trying to get her attention, trying to get in. The poor woman was trying to cope with this great crowd of people.

I honestly don’t feel that there was anything untoward about the way we handled the people in general under the circumstances that existed at the time, which were extremely difficult for everybody, on our side and theirs as well. …

The people were swarming into Cuba, not only from Germany but from many other countries. We had people from 30 or 40 nations, it seemed, all lined up there waiting for their visas.

1941

Destroying Classified Code Books in Yokohama

Noncommissioned officers of the Imperial Japanese Army’s military police, the Kempeitai, in November 1935.

Wikimedia Commons

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Vice Consul Niles W. Bond was spending most days reporting to the Navy Department on Japanese ship movements in Tokyo Bay, which he observed from a telescope on the roof of U.S. Consulate Yokohama. After war broke out, Bond was considerably closer to the action. When Japan’s military police, the Kempeitai, took over the consulate, he and a colleague defied their captors to keep the Japanese from breaking U.S. secret codes.

I turned on the radio and … all of a sudden, the newsreader interrupted and said the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor, and Japan was now in a state of war with the United States and Great Britain.

It was about five-thirty [a.m.] by the time I got that, and so I woke my colleague, the other vice consul. We had some things to burn. … After two or three hours of this, the Kempeitai arrived in force and took over everything. … One thing we had kept, at the consul general’s insistence … he said: “The last things you want to burn are the code books, because we may get a coded message from the Embassy that we will have to be able to read.” So we kept the code books, and they were still there when the Japanese arrived.

The truckload of Kempeitai guards were commanded by a major. He made us go around and open all the files and show him what was inside. He saw the code books. They were in a vault in the consul general’s office, but he didn’t touch them. He didn’t touch anything. He just closed them up and put a Kempeitai seal on them. … This was a mistake on his part, because my vice consul colleague, Jules Goetzman, and I decided that the thing at the top of our list was getting those code books back, out of the vault, and destroyed, before the Japanese got them and read them or used them. …

There were two doors to the consul general’s office, one of which opened into a hallway that led to our apartments upstairs. The other led to his secretary’s office, which was now being used as a sleeping area for the [Kempeitai] guards. The vault that held the code books was right up against the wall on the other side of which they were sleeping.

So we found one night that they had failed to shut tight the one door that we had access to. About midnight … we went downstairs very quietly and carefully opened the vault. Every time we turned the thing we heard this “clunk” inside. It sounded horribly loud to us, but nobody woke up. … We took the books out and closed the safe very carefully. … We had to break the Kempeitai seal, of course, to get in.

My vice consul colleague, Jules Goetzman, and I decided that the thing at the top of our list was getting those code books back, out of the vault, and destroyed, before the Japanese got them.

–Niles W. Bond

Then we went upstairs and spent the rest of the night burning the two code books. We finished between five and six in the morning. … About an hour later, someone knocked on my door: one of the subordinates of the guard detachment. He said, “The major wants to see you downstairs right away.” …

The major took us into the consul general’s office, pointed to the broken seal on the safe, and asked if we knew anything about it. When we nodded, the major ordered us to open the safe. … He saw the empty space where the code books had been [and] demanded that the books be returned to him at once. My colleague replied that they had already been destroyed and offered to show the major the ashes. The major, in a rage probably fueled as much by fear for his own head as anything, drew his sword and demanded an explanation. Recalling a discussion we had had the night before while burning the code books, Goetzman and I, in an inelegant mixture of English and Japanese, endeavored to explain the destruction of the codes in terms of bushido, the traditional samurai code of loyalty and honor.

We pointed out that Americans, too, had such a code of conduct and tradition of loyalty, which demanded that we risk our lives to protect our country, in this case by protecting its codes. My colleague then asked the major what he would have done in the same situation. The major slowly sheathed his sword, drew himself to attention, and then quietly began to weep as he left the room. From that moment on, nothing more was heard from the Japanese about the incident—or about the major, whom we never saw again. But the books were burned, and I was told when I got back to Washington that they were still uncompromised at the time we destroyed them.

President Harry S Truman signs the Washington Treaty forming NATO on April 4, 1949, in Washington, D.C. Secretary of State Dean Acheson stands to his left with the document folder.

Abbie Rowe / National Archives and Records Administration

1949

Creating the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

As chief of the State Department’s Division of Western European Affairs, FSO Theodore Achilles describes negotiating the NATO treaty and how he helped coax a reluctant Portugal into the Alliance that would bring decades of peace to a Europe devastated by World War II.

It would still be several months before we would admit out loud that we were negotiating a treaty. The acting secretary and the ambassadors met once in a while, but the treaty was actually negotiated “despite them” … by a “Working Group,” whose members became lifelong friends in the process.

We met every working day from the beginning of July to the beginning of September. … The NATO spirit was born in that Working Group. Derick Hoyer-Millar, the British minister, started it. One day he made a proposal which was obviously nonsense. Several of us told him so in no uncertain terms, and a much better formulation emerged from the discussion. Derick said, and I quote, “Those are my instructions. All right, I’ll tell the Foreign Office I made my pitch, was shot down, and try to get them changed.”

He did. From then on, we all followed the same system. If our instructions were sound, and agreement could be reached, fine. If not, we worked out something we all, or most of us, considered sound, and whoever had the instructions undertook to get them changed. It always worked, although sometimes it took time.

If our instructions were sound, and agreement could be reached, fine. If not, we worked out something we all, or most of us, considered sound, and whoever had the instructions undertook to get them changed.

–Theodore Achilles

Two years later we began in London to put the “O” on the NAT by creating the organization. Some of the members of the delegations had been members of the Working Group, some had not. I was our representative on one committee; the French representative had not been. He made some unacceptable proposal, and I told him it was unacceptable.

“Those are my instructions,” he said flatly.

From force of habit, I said bluntly, “I know, but they’re no good, get them changed to something like this.” He was sorely offended. A little later in the meeting I made a proposal under instructions I knew to be wrong. He and several others objected. I said, “I know, those are my instructions. I’ll try to get them changed.”

I have never seen a more puzzled-looking Frenchman. “What,” I could see him thinking, “is this crazy American up to? Is he stupid, or Machiavellian, or what?” But he got the idea in due course. …

During the fall the main discussion related to membership. … Of considerable importance was the question of the “stepping stones,” the Atlantic islands. In those days the range of planes was considerably less than it is today, and those islands were considered of great importance should it become necessary to get U.S. forces to Europe in a hurry. The islands concerned were Greenland, which meant including Denmark; Iceland; and the Azores, which meant including Portugal. …

The Portuguese wanted no part in European unity, which they felt would be used both to take over the colonies and undermine her basic sovereignty. Having had this fully explained to me by the Portuguese ambassador, my good friend Pedro Teotonio Pereira, I drafted a personal message from [President] Truman to [Portuguese Prime Minister] Salazar in which I still take a certain satisfaction. It states that we understood and shared Portugal’s reluctance to get involved in European integration or internal continental squabbles, as our whole history showed. Like Portugal, we were [an] oceanic, seafaring, Atlantic power, with a great interest in maintaining the security of the Atlantic area and not just the continent of Europe.

It worked, and the Portuguese joined the negotiations in the last days.

1952

Supporting the Work of Mother Teresa in Kolkata

Mother Teresa, head of the Missionaries of Charity order, cradles an armless baby girl at her order’s orphanage in what was then known as Calcutta, India, in 1978.

Associated Press

Leila Wilson was a comforting figure to many orphans, refugees, and American evacuees during her husband Evan Wilson’s Foreign Service career. While in India she accompanied Mother Teresa through the slums of Kolkata (then Calcutta) and organized the first public effort to fund her work.

We were [in Calcutta] from 1951 to 1953 and we put on a bazaar to raise money for Mother Teresa in 1952. The important point was that it was the first time that anyone ever had raised money for her publicly. She had been supported by the church and communicants before that.

It was through a Roman Catholic friend that I had met Mother Teresa and gone around with her on her rounds through the backstreet busti [the poorest slum areas] of Calcutta … a view that gave me nightmares for a week, beyond which you cannot imagine anything more horrible. But it was that that convinced me that here was something we could do, no matter how little money. We only raised about $3,000, but it was a fortune as far as she was concerned. We thought we’d done pretty well, because it was a bazaar participated in basically by Indians. We had silly games of chance, we had dancing, we had people who sang and people who ran booths of entertainment so that there was something for everybody to do, and of course food.

I was in charge. I was the head of the [American Women’s] club, and there was a group of us who kind of fought our way through. There were those who thought we should not support Mother Teresa, because she was not Hindu. Anyway, it was argued out, and we decided to do it, because it was Hindus, Moslems, anybody who was dying and in terrible shape, leprosy and cholera and typhoid and tuberculosis patients that she was ministering to day by day and running little schools of sorts for their children.

She could at least give them love and hope, and it was a pretty emotional thing to go around and see what she was doing and accomplishing with just plain nothing.

–Leila Wilson

… She had been teaching in a sophisticated school for Indian girls in Calcutta. She decided she had to leave that way of life and devote herself to those who were totally poverty-stricken and totally helpless and hopeless. She could at least give them love and hope, and it was a pretty emotional thing to go around and see what she was doing and accomplishing with just plain nothing.

… They had a very simple house, minimal rooms, minimal equipment, just running water. I think they had electricity, but nothing elaborate whatsoever. But it was organized, and she had six or seven nuns working with her in 1952. All the reports describe her as having begun her mission in 1952, so we were really in there on the ground floor.

1958

Combating Malaria in Ethiopia with USAID

Dr. Julius Prince pioneered international programs to train local health workers as head of the Public Health Division in the Ethiopia Mission of what would soon be known as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). With malaria killing thousands each week, Dr. Prince recounts how the mission supported the Ministry of Health’s efforts to rapidly respond to the epidemic.

I had been interested in international health problems. … I was completely “converted” to the belief that we are not … “an island.” And similarly, I believed that we have to be concerned about the health of people in other countries, because everything is related to everything else. So that is the philosophical reason why I wanted to do this kind of work.

We have to be concerned about the health of people in other countries, because everything is related to everything else.

–Dr. Julius Prince

The minute I got off the airplane in Addis Ababa my staff was there and said: “Dr. Prince, come on, we’ve got to get to work with the ministry. Ethiopia is in the grip of a terrible malaria epidemic.” And never having had any experience with malaria epidemics, I was astonished. The reasons why such things apparently … exist are … the epidemic’s likely relationship to the peculiar ecology of the country and lack of malaria immunity among the relatively high-altitude inhabitants, who were usually not exposed to the disease.

Basically, it had to do with the altitude and meteorological conditions necessary for mosquitoes to breed under certain conditions. But in 1958 things were just right, we suspected, in terms of temperature, humidity, rainfall, and the like, for mosquitoes to breed in locations even well above 5,000-foot altitude.

Well, we went directly to the Ministry of Health that morning and joined the planning already underway. And the only thing to do was rapidly to get as much chloroquine tablet medication as possible into the country and distribute it for emergency treatment of all individuals found to be febrile as widely as one could over the affected areas and also do that as rapidly as possible; for time was of the essence. It was mainly a logistics problem; and that is what the Ministry of Health undertook. From the mission we sent cables to the U.S., U.K., and Kenya to try and obtain chloroquine tablets in sufficient amounts and in the shortest possible time to deal with this enormous epidemic.

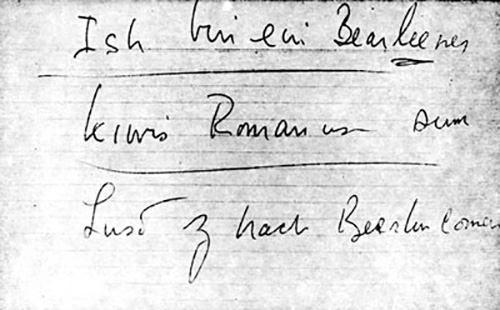

U.S. President John Fitzgerald Kennedy gives the 1963 public speech in West Berlin where he famously said, “Ich bin ein Berliner.”

Keystone Press / Alamy Stock Photo

1963

Giving President Kennedy His “Ich bin ein Berliner” Line

John F. Kennedy’s phonetic transcription of the German and Latin phrases in the “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech, West Berlin, 1963.

Wikimedia Commons

Growing up as the son of the Associated Press Bureau Chief in West Berlin, U.S. Information Agency Officer Robert Lochner possessed language skills that were invaluable when President John F. Kennedy came to the divided city, where Lochner was directing “Radio in the American Sector” broadcasts. He served as Kennedy’s interpreter throughout his historic visit to West Germany, coaching the president on his German pronunciation and translating the line that sent a poignant message of solidarity in the depths of the Cold War.

A few weeks before [Kennedy’s] visit I was called to Washington and [National Security Adviser] McGeorge Bundy asked me to prepare a few simple phrases in German and to try to rehearse those with the president. So on a typewriter with large letters I prepared a few very simple sentences. McGeorge Bundy took me into the Oval Office, there was nobody else there, and presented me.

I gave one copy to the president and slowly read out the first sentence in German and asked him to repeat it. When he did and looked up, he must have seen my rather dismayed face, because he said, “Not very good, was it?”

So what do you say to a president under those circumstances? All I could think of was to blurt out, “Well, it certainly was better than your brother Bobby.” He had been to Berlin and tried some sentences in German and had butchered them in such a fashion that one couldn’t possibly guess what he was trying to say.

So fortunately the president took it lightly. He laughed and turned to McGeorge Bundy and said, “Let’s leave the foreign languages to the distaff side.” Of course, everybody knows that Mrs. Kennedy spoke fluent French. So he had not intended to make a single statement in German. …

I interpreted for him the whole three days that he was in Germany starting at the airport in Bonn. The receptions in Bonn, Cologne, and Frankfurt were as enthusiastic as you could wish, but the one in Berlin overshadowed everything that we had experienced in Western Germany. …

When we stopped for his major speech and walked up the stairs to the City Hall, he called me over and said: “I want you to write out for me on a slip of paper ‘I am a Berliner’ in German.”

When we stopped for his major speech and walked up the stairs to the City Hall, he called me over and said: “I want you to write out for me on a slip of paper ‘I am a Berliner’ in German.”

–Robert Lochner

We first went to [West Berlin Mayor] Willy Brandt’s office while hundreds of thousands cheered outside. I quickly, by pencil, wrote it out in capital letters and he rehearsed it a few times. And that is really the whole story. …

After the speech we came back for a little while to Willy Brandt’s office where there was a short reception with some of the top politicians; and, of course, I had instructions to stay close to the president in case he talked to some Germans.

So I couldn’t help overhearing McGeorge Bundy saying to him, “Mr. President, I think that went a little too far.” So, McGeorge Bundy, like myself and many others, instantly realized that his making this statement in German gave it that much more weight than if he had said it in English. …

The president seemed to agree … and then and there made a few changes in his second major speech later on at the university, changes that amounted to making a few more conciliatory statements, if you wish, toward the East. …

It didn’t have any effect on the famous statement, of course, but it is interesting to me that McGeorge Bundy, like myself, had this instant reaction that the statement was that much stronger for having been made in German, and millions of Germans since then have repeated his “Ich bin ein Berliner” while they probably would not have quoted “I am a Berliner.”

1966

A Bizarre Diplomatic Hostage Crisis in Guinea

FSO Robinson McIlvaine arrived as U.S. ambassador to Guinea after President Sékou Touré had granted asylum to deposed Ghanaian President and fellow Marxist Kwame Nkrumah, appointing him honorary “co-president” of Guinea and outraging Ghana’s new revolutionary government. McIlvaine soon discovered how representing the United States can make diplomats a target, even when the dispute is between African rivals. McIlvaine also served as ambassador to Dahomey [now Benin] and Kenya.

We were the first diplomatic hostages. That was before Tehran. The entire American community, everybody in U.S. Embassy Conakry, all the Peace Corps—we had several hundred Peace Corps volunteers—were all put under house arrest, and there was a big brouhaha about that. It happened within days of our arrival. …

There was a meeting coming up of the Organization of African Unity, OAU. The foreign minister of Guinea, Mr. Beavogui, was going to that meeting. … Anybody going to Addis Ababa from the west coast had to go on Pan Am. So all the other foreign ministers were getting on as the plane went down the coast.

[The plane] came to Accra, Ghana, where Kwame Nkrumah had been overthrown, and the new “revolutionary government” wanted his hide. They saw that the Guinean foreign minister was on the plane; and they went on and roughly hauled him off and arrested him. … The Ghanaians then told Sékou Touré: “All right, you want your foreign minister back? Give us Kwame Nkrumah.”

…The first thing we knew of [our house arrest] was on a Sunday morning. … DCM Charlie Whitehouse was coming around to pick us up. I went to the gate, and there was a soldier there on guard. Charles came to the gate, and couldn’t get in, and I couldn’t get out. So we wanted to know what it was. The soldier didn’t know.

He said, “Oh, well, there’s been some problem. It’s very serious. You have captured our foreign minister.” I said, “I have?”

–Robinson McIlvaine

We finally reached the top civil servant in the foreign ministry, and he said: “Oh, well, there’s been some problem. It’s very serious. You have captured our foreign minister.” I said, “I have?”

The long and the short of it was, you see, [the Guineans had] put two and three together. Because it was a Pan Am plane, that made it an official plane: it must be a CIA plot. We were the tools of that regime in Accra, Ghana. So, by God, they were going to sit on me and all the other Americans until the Ghanaians gave up the Guinean foreign minister. …

A mob had been organized … brandishing signs about “A bas l’imperialism américain [Down with American imperialism]!” There were about 3,000 people all milling around the chancery, and then I heard on the radio from my wife that a similar group was doing the same thing at the residence. Well, that one got out of hand, broke all the windows, and it was pretty scary for my wife and two kids, who were then 3 and 2. They were all holed up in the second floor, and these characters came through the windows. The long and the short of it was that in the end, nothing much was done except breaking all the windows. …

I’ll never forget, after the mob went away, and my wife came down. I hadn’t gotten home yet, but she went down, and she started with a broom to sweep up all the broken glass, and a little guy appeared out of the bushes and said, “Oh, no, madame, we did it. Let me sweep it up.” And he took the broom from her and swept it up. …

I got to see Sékou Touré at 3 in the morning after we discovered we were hostages … and, I believe, convinced him that we had nothing to do with the kidnapping of his foreign minister. However, the Americans were Touré’s only leverage on Ghana. So he did not release us until his foreign minister was returned about 10 days later.

1975

Evacuating Refugees as Saigon Falls

South Vietnamese refugees walk across a U.S. Navy vessel. Operation Frequent Wind, the final operation in Saigon, began April 29, 1975.

CPA Media PTE LTD / Alamy Stock Photo

Foreign Service Officer Mary Lee Garrison arrived at her first assignment in Saigon’s consular section in the waning months of the U.S. presence in Vietnam. She soon found herself scrambling to give refugees whatever documentation could be mustered to get them on flights to safety.

Junior officers were pulled off or brought up from the various consulates and sent out to the airport. The Immigration Act basically got thrown in a cocked hat. I was supposed to try to follow the revised rules that we got from Washington in the consular section, but out at the airport what they were doing was taking a look at the folks who showed up and making an assessment whether they had half a prayer of making a life in the States, and if they did, they put them on a plane. …

The rules went out the window. … You had to be practical. I found it very difficult, though. This was my first assignment in the Foreign Service. I was all of, at the time, 22 years old, and you find yourself making literally life-and-death judgments, and that’s not easy.

There is one, one thing that’s going to haunt me until the day I die. It was the case of a sergeant in the military who married a woman with several children from a previous marriage. Several is an understatement. I think there were six, and they had several of their own. … This was not the 18-year-old marrying a 24-year-old bar girl. This was a sergeant of some standing marrying a mature woman with whom he fell in love. And right before the family was to leave for the States, grandma convinced two of the kids not to go, one of the girls and one of the boys. In the confusion when they got to port of entry in the States, one of the girls who was close in age ended up using her sister’s immigrant visa.

This was my first assignment in the Foreign Service. I was all of, at the time, 22 years old and you find yourself making literally life-and-death judgments, and that’s not easy.

–Mary Lee Garrison

It took us ages, over a year—because the case started before I even got to Vietnam—before we could get to the truth of who had traveled and who hadn’t, and then try to get new immigrant visas issued for the two children who had stayed behind. The girl by this time was about 14 and the boy was 12 and able to be drafted. They had been actively trying for a good six months by March 1975.

The last I saw of them, I handed the girl the files that we had; we took the petitions and everything else related to it and were starting to put them into manila envelopes, initial them, seal [them] with the consular seal and tape them shut and hand them to folks who we presumed were getting on the evacuation flight, saying, “Give this to the Immigration and Naturalization Service when you get there”—because we were so far from any possibility of doing visas then.

I gave them to her, and I said, “See if you can get your brother out to the airport and give them this.” … I still don’t know if they got out.

1977

Documenting the Plight of Argentina’s “Disappeared”

As one of the early officers to take on a human rights portfolio in the Foreign Service, F. Allen “Tex” Harris became a point of hope for thousands of families in Argentina whose loved ones had been kidnapped, tortured, and clandestinely executed by the military junta during the so-called Dirty War. Documenting nearly 14,000 cases, his work changed public perceptions and government policies around the world.

Well, what I did was very straightforward. I opened the door to the embassy, and people started coming. Then we worked the operation like a high turnover doctor’s or dentist’s office. We had two inside offices. Blanca Vollenweider [a USAID employee who assisted Harris] put the people in the office, and she took down on a five-by-eight card—this was before computers—their name, their address, their telephone number, the name of their child or relative that had disappeared or friend who had disappeared, the date of the disappearance, and that was it. … If they had any papers, she took the papers from them, or any papers that they had filed with the police or other governments.

Then she would go out, I would come, and I would interview the person, generally in Spanish … getting the facts, writing the information down on the card, and then I would thank them, and I would leave. I would go into the other office … and I would interview. Meanwhile Blanca would go back, escort the first interviewee to the elevators … and bring in the next person who wanted to report the disappearance of a loved one, and take their information. Then I would come from office number two to office number one, and we did this ping-pong every afternoon. …

Here was this great big, huge guy … easy to spot, easy to point to; and, lo and behold, the United States of America is interested in the disappearance of their children. That meant a lot to them, and it meant a lot to me to be able to do that.

–Tex Harris

Now there were literally 13,500 disappearance cases that came to our attention during the time that we were collecting information. We sent what was probably the largest airgram ever sent to the Department of State listing the names of the Disappeared. … When I visited Washington after coming back from Buenos Aires, on both the desk officer’s desk and in the Human Rights Bureau, there was our airgram out there in piles A to F, G to M, and all the other parts of the alphabet with markers on them, so that when somebody called and they complained about information on a disappearance, they would go and look in the airgram and find the page where we had xeroxed two to a page our five-by-eight cards, so the airgram was about 700 pages in length. …

I became extremely close to a number of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. … Every Thursday afternoon they would gather in front of the Casa Rosada, the Pink House, and march around with signs. … I would go to the Plaza de Mayo, not every Thursday but I would go often. … There wasn’t anything that I could really do to bring their kids back. [But] here was this great big, huge guy … a 250-pound, six-foot-six, two-meter fellow who pitches up and is easy to spot, easy to point to; and, lo and behold, the United States of America is interested in the disappearance of their children. That meant a lot to them, and it meant a lot to me to be able to do that.

I got to know a lot of the mothers and the supporters of the mothers and became friends with them. It was really tough, because these were people who were just going through not only the hell of losing your child—the ritual of going to the gravesite was terribly important in the culture—these people didn’t have a body to bury. These people did not have any information as to how their children died or if their children were still alive or if they were being tortured or if they were in great pain, so the emotion and the suffering that these folks went through was absolutely horrific.

Aurelia “Rea” Brazeal speaks at an American trade fair in the early 1980s during her tour as trade officer in the economic section of U.S. Embassy Tokyo.

Courtesy of Rea Brazeal

1981

Restraining Japan’s Auto Exports to Preserve American Jobs

As trade officer in the economic section in Tokyo, Aurelia “Rea” Brazeal took on coverage of the auto sector, contributing to negotiation of the voluntary export restraint agreement that limited the export of Japanese cars to the United States, protecting the jobs of U.S. auto workers. The first Black woman to rise from the entry level of the Foreign Service to ambassador, Brazeal drew lessons from her work protecting American industry.

With the Japanese, we moved from complaining about one particular product to talking to them about entire sectors, and we also began structural adjustment talks. For automobiles, of course, the voluntary export restraint [VER] agreement was negotiated [restricting the annual import of Japanese-made passenger cars to 1.6 million units for three years]. I think on the economic side, we were making progress in terms of levels of sophistication to understand that you can’t solve economic problems writ large by negotiating product by product. You have to talk sector by sector, or especially systemically. …

The Japanese were making smaller, more fuel-efficient cars, but Americans weren’t buying them in large numbers, until the first oil crisis, where we had long lines in this country for gasoline; at that point Americans saw the attraction of a smaller, more fuel-efficient car. The Japanese had the product and the inventory, so sales really increased. …

I’d always believed we made a mistake as a government on the voluntary export restraint agreement, because, from my point of view, we should have extracted an agreement from the U.S. auto industry that it would use the time frame of the VER to make changes and become competitive. … The U.S. auto industry, from my point of view, pocketed the protection they got from the VER and kept doing business the same way as before. …

We were making progress in terms of levels of sophistication to understand that you can’t solve economic problems writ large by negotiating product by product. You have to talk sector by sector, or especially systemically.

–Rea Brazeal

I do support what’s generally considered free market economics and also the global trading system. And I do agree that it’s very difficult for governments to pick winners and losers; and ours, by and large, shouldn’t try to do that, because we’re really not very good at it.

But, that said, if you are going to give protection to an industry … as a government, we should extract something from that American industry that would press it to take steps to become competitive. In the steel industry, you can see we’ve lost the huge steelmaking plants, but what we have gained are niche steelmaking companies where we are still very competitive; people did retool, and those who are in business now are much more competitive, even internationally, than they would have been, I hope, had no protection been given.

I think you have to acknowledge some role for government that isn’t too intrusive; but governments usually step in with protection for any number of reasons, most of them political and not economic. …

Both sides [saw] a maturing of the relationship to the point that you could get to talk about the structural issues … because they could be an engine for growth globally, as opposed to the U.S. having the only engine. They could burden-share, if you will, the responsibility for growth. …

There are very few embassies around the world that influence or affect economic policymaking, and Tokyo is one. And, therefore, that is another illustration of the importance of the relationship, because our reporting out of Tokyo could affect decisions made in Washington vis-à-vis our own economy and how we saw things, and I think that is important.

After medical examinations at a U.S. base in Europe, Americans held hostage aboard the Italian cruise ship Achille Lauro depart for the U.S. aboard a military aircraft.

U.S. Department of Defense

1985

Assisting American Hostages from the Achille Lauro

The Achille Lauro.

Ajax News & Feature Service / Alamy Stock Photo

After surviving his own detention by Palestinian guerrillas in Beirut 10 years earlier, FSO Edmund James Hull was deputy political counselor in Cairo when four Palestine Liberation Front terrorists hijacked the cruise ship Achille Lauro off the coast of Egypt with 11 Americans aboard. After the hijackers surrendered and the ship approached Port Said, Hull tells below of boarding to identify and assist Americans on board, then accompanying them to Italy, where in a stunning turn of events, they were able to identify the apprehended hijackers. Hull went on to become ambassador to Yemen.

We knew [the ship] was coming into Port Said. So Ambassador [Nicholas] Veliotes asked me to accompany him to Port Said. I had a few minutes to pull my thoughts together, which included such practical things as getting a list of the names of the hostages as we knew them, and then we drove up to Port Said. … We actually met the boat at sea in Egyptian waters before it was able to come into Port Said. … We got onboard, and we found a traumatized crew and passengers.

The hijackers had already been removed from the boat so … the first thing we did was to verify the well-being of the American citizens onboard. It was early morning, and the passengers were asleep in their cabins. I had my list of American passengers, so I systematically went around knocking on cabin doors. I found all but one passenger.

Meanwhile, Ambassador Veliotes had engaged with the crew, who didn’t have a lot of English but who were by gesturing and pantomime explaining to us that something had happened … Leon Klinghoffer, an old and infirm American, had been killed by the terrorists. He was in a wheelchair at the time, and his body had been dumped over the side. The crew took me to the location, and you could still see on the side of the vessel bloodstains from where Mr. Klinghoffer’s body had struck the side in going overboard. … We had a very difficult situation because not only did we have the problem of taking care of the hostages, but now the Egyptians were really on the spot because the hijackers, who had been taken into custody, were now clearly guilty of murdering an American.

On the way back to Port Said, my primary mission was to try to take care of the hostages as best I could, and that meant trying to give them assurances that now they had U.S. government representatives there to help them, that their needs would be taken care of, that Klinghoffer’s murder would be pursued. … One thing that I decided would be good to do to fill the time would be to have all of them sit down with pen and paper and to write out an account of their experiences. That would give something written for the Egyptian investigators. …

When we finally got in Port Said … we were joined by the regional psychologist from Embassy [Cairo]. We … boarded a C-130 to be flown to Germany for medical examinations. I accompanied the hostages.

I had my list of American passengers, so I systematically went around knocking on cabin doors. I found all but one passenger.

–Edmund James Hull

In midair, we had news that American military aircraft had intercepted the Egyptian airplane that was taking the terrorists from Egypt to Tunisia, which at the time was the headquarters of the Palestine Liberation Organization. President Reagan had made the decision that we would intervene and force the Egyptian airplane down at the U.S. Naval Air Station in Sigonella, Sicily. …

We were diverted from Germany to Sigonella to give some of the hostages the opportunity to identify the terrorists, and that process took place at the military base. We were joined there by the team from [U.S.] Special Operations Command, which had been shadowing the Achille Lauro at sea. So, we had an interesting situation in which the hostages, the terrorists, the U.S. special operations personnel, and U.S. diplomats were colocated and to some extent could discuss the incident.

At that time, I learned the special ops team had been prepared to storm the vessel. The hostages … expressed relief that it had not occurred. … At least some of the hostages believed that if the storming had occurred, the hijackers would have opened up with automatic weapons, and there would have been many casualties.

1992

Demobilizing Insurgents in El Salvador

When mid-level insurgent commanders began resisting the final stages of the negotiated demobilization of fighters in El Salvador, Chargé d’Affaires Peter Romero took to the hills to speak to them himself. The next year, Romero was appointed U.S. ambassador to Ecuador and later the department’s first Hispanic assistant secretary for Western Hemisphere affairs.

It was the last week before the guerrillas had to demobilize completely; they demobilized in stages, and of course they kept their best guns and their best fighters for the last iteration of demobilization.

We were called by a contact who had been the deputy head of one of the largest guerrilla-fighting factions. The FMLN was the umbrella group, the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front, and then you had five factions of fighters underneath that umbrella. And the largest one was a group called the ERP, the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo, and these were some hard-fighting guys, and they were supposed to have demobilized their last units, which were their crack units. … [U.N. Secretary General] Boutros Ghali, because this was a U.N.-sponsored event, the critical stage of the peace process … was coming down to bless the demobilization of the guerrillas and the demobilization of the quick reaction battalions in the army.

I talked to my subordinate who had close contacts with the deputy of this particular ERP faction, because he had warned that the mid-level commanders weren’t demobilizing, they didn’t see anything in it for them, they expected to have benefits. … This was the last faction. Boutros Ghali is expected in literally a matter of hours.

[I was told] that the mid-level commanders … were all meeting on the slopes of the San Salvador volcano at a Catholic orphanage.

“Find out where it is,” [I told my subordinate] … “because we’re going.”

He said, “You can’t just show up to a meeting with these guys. These guys will kill you.”

I said, “No, they won’t kill us. They’ll be surprised, but I have to talk to them, because their superiors have obviously lost control of them. They’re the last ones, and talking to us might make a difference.”

I said, “… I have to talk to them, because their superiors have obviously lost control of them. They’re the last ones, and talking to us might make a difference.”

–Peter Romero

So without any instructions, I did it. … We had six hours of meetings with these guys. … All of the “imperialist” acts of the last 40 years I had to answer for. And then the discussion got on to what they cared about, and that is that they had been sold a bill of goods, that they felt that they would be left destitute, that they had fought hard for all of these reforms that were being enacted and that they should have something to show for it, other than basically dropping their guns and going home.

We had put lots of benefits out there to assist the Salvadoran government. You could go back and complete high school, you could go to college … you could get a small parcel of land, you could get vocational training. We had all kinds of stuff in place for both sides, for both the demobilized military and demobilized guerrillas.

But they expected a cash payment, and I had to tell them: “You’re not getting a cash payment, but there’s lots of things out there that would be really good.” … We had … about $300 million a year for a country of 5 million people, so we could do a great deal to assist with demobilization and reform.

And we walked through all of this, and then this little commander—I remember so distinctly—in the back of the room raised his hand and said: “I always dreamed of having my own auto parts store. You think I could get a visa to go to the United States and buy auto parts for my store?”

“Absolutely,” I said. And after that the conversation turned to “Maybe I’ll go back to college,” “Maybe I’ll start my own business,” “Maybe I’ll start that little grocery store that I always wanted.”

The whole thing changed. They demobilized, Boutros Ghali came, Vice President [Dan] Quayle came down, [it] was a resounding success.

1994

Securing and Eliminating Kazakhstan’s Nuclear Arsenal

When FSO Janet L. Bogue took over as chief of the political, economic, and science section at U.S. Embassy Almaty, the State Department was focused on securing the nuclear assets of the Soviet Union’s successor states. Bogue soon found herself in the middle of Operation Sapphire, a secret project to remove Kazakhstan’s highly enriched uranium.

One day … the science minister was skiing with a colleague of mine, and said to him at the end of day, “Do you mind if I tell you a secret?”

The fellow said, “Well, no. Go ahead.”

[The minister] said: “Well, we have around 500 kilograms of highly enriched uranium, which could be made very easily into warheads. We would like to get rid of it. We would like you to have it. We would like you to box it up and take it away. And we would like this all done quietly so that nobody grabs it in the meantime or starts bidding for it.”

The U.S. government at first wanted nothing to do with it. We could not get anyone interested—although that didn’t stop all of them taking credit once it happened. Finally, the U.S. government agreed that we could move this 500 kilograms of highly enriched uranium from Kazakhstan to safe storage in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. It was a highly secret project called Operation Sapphire. The reason it was so secret is that once the stuff, the uranium, is bundled up in a safe way, this is the best time for the bad guys to take it because it is safe for them to grab. There had already been cases in the former Soviet Union of someone walking out of a facility with a briefcase full of unprotected things and dying three days later in a hotel room of radiation poisoning. …

First the U.S. government said, “It can’t be highly enriched uranium.” So the embassy actually went and took samples of it and sent them back. Sure enough, it was. Finally, reluctantly, the U.S. government … negotiated a deal in which, essentially, we would purchase it. …

It really was one of those moments in your career when you felt like, “I actually did a concrete thing that made the world safer.”

–Janet L. Bogue

The whole project was well over a year, including bringing over a whole crew of fellows from Oak Ridge, who lived up at the site while they did what they had to do to package up the uranium in what almost looked like little beer kegs. They are lead and make it possible for you to move it in a safe way. Then, flying in C-5s, huge cargo aircraft … they flew straight to the States with midair refueling. …

They landed at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. The material was transferred onto a truck convoy, highly protected, and taken straight to Tennessee and put deep underground. Once that was announced Secretary [of State Warren] Christopher, Secretary [William J.] Perry of the Defense Department, and Secretary [Hazel] O’Leary of the Energy Department all did a press conference.

It was very late at night already in Kazakhstan, but we all converged on a colleague’s house and brought some vile, sweet Kyrgyz champagne from the champagne factory there. It really was one of those moments in your career when you felt like, “I actually did a concrete thing that made the world safer.” Five hundred kilograms of highly enriched bomb-grade uranium is stuck away where whoever in this neighborhood, or whatever rogue elements, cannot get at it. That was a wonderful thing. …

It was old-fashioned human diplomacy. It was the fact that one of our guys was out skiing with the science minister, because they had developed a very friendly relationship and they liked to ski together. The science minister had developed enough confidence over time that he felt he could pose this question on behalf of his government.

1996

Supporting Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa

President of South Africa Nelson Mandela (right) with Bishop Desmond Tutu in Cape Town, South Africa, in 1994.

SIPA USA / Alamy Stock Photo

In the wake of Ambassador Edward Perkins’ work to bring an end to apartheid in South Africa (read the FSJ’s interview with Ambassador Perkins in the December 2020 issue), Aaron Williams became one of USAID’s mission directors in Pretoria and led programs supporting the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), the core of South African efforts to deliver transitional justice. Beginning his career as a Peace Corps volunteer, Williams retired after 22 years with USAID and returned to the Peace Corps in 2009 as the first Black man to serve as director. For an on-the-ground view of the fall of apartheid in South Africa, see also the oral history of six-time Ambassador William “Bill” Swing on ADST’s website.

We funded a portion of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s budget, as did other donors, e.g., the British, the Canadians. … We contributed significant funding to cover some of the operating costs. … And I traveled and observed the TRC hearings all over South Africa. The commission was national in scope, so they had regional hearings in every region. Archbishop [Desmond] Tutu, as chairman, would often travel to chair a specific hearing of national importance. The hearings were very complex and well-planned sessions.

The hearing I vividly remember was held in Paarl, in the Cape Town region, in the heart of the wine country. This beautiful, idyllic part of South Africa had been the locale for terrible, heinous crimes during the apartheid era.

I took Assistant Secretary [for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor] John Shattuck to attend one of the 26 hearings. … Susan Rice [then National Security Council senior director for Africa] also accompanied him to this hearing.

The hearing was at a local school. They had the stage in the auditorium surrounded by flowers. The families of the victims and the perpetrators were seated in separate sections of the hall. The process allowed the accused to present themselves to apologize and express their contrition for what they had done and ask for reconciliation and amnesty. Translators were present to manage the five major languages of South Africa, and the hearing used simultaneous translations. Psychologists were on the scene to deal with the anticipated emotional breakdown of the accused and/or the victims’ families during and after the testimony. … Obviously, heavy security was in place. It was a surreal setting.

Archbishop Tutu chaired the hearing. This was a case where a young Black man had disappeared in Paarl region, and his family wanted to know what had happened to him in the 1980s. He had gone out drinking with his friends in a bar. He never came home—he had disappeared 10 years ago.

Archbishop [Tutu] was just crying, due to the emotional toll that this had taken on him. But he also said that these were also tears not just of sorrow but of joy because people were confronting their demons in a way that could improve the greater society.

–Aaron Williams

The local police commander of the squadron that killed him came forward to testify and admit to his guilt. Turns out that the young man that they killed was not an anti-apartheid activist. He was just in the wrong place at the wrong time in that bar. They killed him and buried his body by the river. The policeman pointed out where the body was so that his remains could be recovered. The man’s widow was there with his children. A tragedy, one of hundreds of thousands that occurred during the apartheid era.

In the second case, the accused were ANC [African National Congress] cadre that had kidnapped an Afrikaans policeman, then tortured and killed him. After that they tossed the body in a pit, never to be recovered. These men came forward and testified and described the events of that night. They asked for amnesty, and of course the victim’s family was present in the hall.

We took a break after two hours of these heavy-duty emotions. We went to a break room to join Archbishop Tutu and the rest of his commission for coffee. … The archbishop was just crying, due to the emotional toll that this had taken on him. But he also said that these were also tears not just of sorrow but of joy, because people were confronting their demons in a way that could improve the greater society.

It was just one of the most emotional, heart-wrenching days that I had ever experienced, and I believe that it was the same for most of us in that school that day.

No country has been able to replicate the TRC’s process with the effectiveness of the South African authorities. … President [Nelson] Mandela … was an extraordinary leader and certainly a unique figure in the 20th century, someone who had achieved the impossible in many ways, a feat that most human beings are incapable of doing, which is to set aside anger and hate and disappointment and suffering. To have the courage and determination to ignore such powerful human feelings and look to the future in a positive manner. To set forth on the path to reconcile a diverse nation that had lived through the injustice, pain, and tragedy of the apartheid era. To give hope and democratic governance as a platform for a historic transformation the likes of which the world had never seen.

Very, very few people in humankind’s history have ever been able to accomplish such monumental things.

On Dec. 26, 2004, a powerful earthquake and resulting tsunami struck in the Indian Ocean with a devastating impact on coastal Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, and Thailand. Banda Aceh, Sumatra, shown here, was one of the hardest hit areas, with the highest death toll and destruction of most homes. U.S. military personnel assisted local authorities using helicopters to transport supplies, bringing in disaster relief teams, and to support humanitarian airlifts to tsunami-stricken coastal regions.

U.S. Navy

2004

Disaster Assistance After the Indian Ocean Tsunami

After serving as ambassador to Malaysia, Marie Therese Huhtala returned to Washington as the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs deputy assistant secretary covering Southeast Asia. Just months into the job, the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami hit, wiping parts of the territory off the map. Ambassador Huhtala shifted full time to coordinating U.S. emergency assistance to the devastated region. For a U.S. Embassy Jakarta account of coordinating civil-military rescue efforts in Aceh, see also Ambassador Lynn Pascoe’s forthcoming book in ADST’s Diplomats and Diplomacy series: Dealing with Dragons, Bears, and Some Nice People Too: A Diplomatic Chronicle.

On December 26, the Asian tsunami struck. The whole EAP [East Asia and Pacific Affairs] Bureau worked around the clock from that day on to coordinate the U.S. government response and facilitate various trips out there. [Secretary of State] Colin Powell set out immediately to visit the region, so we put together a briefing book for him on a crash basis. At the same time the State Department had a task force going, we were working to put together assistance, and to get the U.S. military engaged. The province of Aceh in Indonesia was absolutely devastated. It was just scraped clean, the town of Banda Aceh on the coast was obliterated. …

We had a carrier battle group, the USS Lincoln, that was in liberty in Hong Kong on the day the tsunami struck. It was on its way home from the Persian Gulf. Admiral [Thomas B.] Fargo, the commander of Pacific Forces, turned them around that very day, the day of the tsunami, and they began steaming for Indonesia. They got there by January 1 and began providing assistance. The U.S. was, by any measure, the first nation to respond.

It was chaotic, dangerous and hotter than hell. But by golly, they did fabulous work.

–Marie Therese Huhtala

We also had a Marine battle group, the Belleau Woods, on its way to the Persian Gulf, that was diverted and sent to Aceh. Those two battle groups did an absolutely fabulous job saving lives. In Aceh, there was no clean water, no food, no medical facilities; the military provided all of that to survivors.

We also brought a hospital ship, the USS Mercy, which arrived about a month after. But the crucial thing that the first responders did was to bring in bladders of clean water and to send their helicopters out for search and rescue because there were a lot of people trapped in isolated areas. The coast road had been destroyed. They plucked them out and brought them to safety. It was very, very impressive. Of course we immediately began getting food out there, as well.

I got to see it twice. Paul Wolfowitz, the deputy secretary of defense, went out to visit in February, and I went along on that trip. He was a former ambassador to Indonesia and was very deeply concerned about the tragedy; he also wanted to observe the heavy military involvement in the relief effort. Then I returned in early May when Bob Zoellick, who was now deputy secretary of State, went out. I saw in the two and a half months interval that there had been some progress in cleaning the debris and very tentative attempts at rebuilding. But it was clear that the region was going to take a generation, at least, to recover. …

That first time we landed on the airstrip at Banda Aceh, it was like a scene out of “Apocalypse Now.” It was crazy. We arrived on a C-130 from Thailand that was loaded with food, really well supplied. The aircraft parked in the middle of a landing strip, and we got out. My God, there’s a helicopter zooming by! And here there are people coming over to greet Wolfowitz, right under the shadow of the plane. Somebody else has the back door open, and they’re taking out relief supplies; here comes another plane landing from some Dutch NGO. It was chaotic, dangerous, and hotter than hell. But by golly, they did fabulous work.

2014

Keeping India’s Khapra Beetles and Other Pests Out of U.S. Food Supplies

Prem Balkaran, an inspector with the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, examines mangoes being packaged for shipment to the United States. Inset: An irradiation seal (pictured here) certifies that irradiation has sterilized any insects that might have infested the mangoes inside this box, making the fruit safe for export to the United States.

Courtesy of Allan Mustard

As agricultural minister-counselor in New Delhi, Foreign Agricultural Service FSO Allan Mustard oversaw USDA programs to keep invasive pests such as khapra beetles, a serious threat to American grain supplies, out of India’s agricultural shipments to the United States. Mustard went on to become U.S. ambassador to Turkmenistan.

The big issues were basmati exports to the United States and exports of mangoes, because India is the home of the khapra beetle, which is the absolute worst quarantine pest you can imagine. We required that all basmati rice shipped to the United States come from a limited number of facilities that met APHIS [Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service] standards for insect control, and this included use of stainless steel silos for storing the rice in bulk. They would not use burlap bags; they would only use polypropylene bags for shipping the rice, because burlap is a natural habitat for the khapra beetle. They eat it, then they breed, so you know, you had to take all these measures to make sure that there would be no khapra beetles.

Then of course there were very stringent inspection requirements. So any basmati rice shipped to the United States from India could only come under these rather stringent conditions, which cost money, and that was the complaint. Burlap is cheaper in India than polypropylene, why do we have to do this? This is unfair. It’s a trade barrier. … No trade barrier, we’re not barring your trade. We want your rice. We just don’t want the khapra beetles to come with it.

Similar thing with the mangoes; everything had to go through a radiation facility to sterilize any insect pests [such as fruit flies] that were in the mangoes, and that way when the mangoes arrived in the United States, if live insects came out, they would be sterilized, they wouldn’t be able to reproduce. Again, it was expensive to ship all your mangoes to this one place, have them irradiated, pay for the irradiation, and then take them to the airport, put them on a plane, and fly them to the United States. We also required special boxes that had to be sealed so that insects couldn’t get in after they were irradiated. So for every box of mangoes that went, there was a certain cost associated with meeting our standards, and they resented that. I just had to tell them, look, it’s this or nothing, either do this or your mangoes don’t go to the United States. …

Indians constantly complained about this because it meant that all the mangoes that were shipped to the United States had to come to one facility, go through the irradiation, that could only be done while the APHIS inspector was present to make sure there was no monkey business. They had to pay for it, they had to pay for his room and board, they had to pay for all of his expenses, they of course had to pay for the transportation to the facility, the operation of the facility, and then they would ship these mangoes by air because mangoes have a very short shelf life. You have a shelf life of five days so then you would put them on a plane, you ship to the United States, by the time you get there the shelf life is about three days, you put them out on the street, and you try to sell them as quickly as you can before they spoil.

There was a certain cost associated with meeting our standards, and they resented that. I just had to tell them, look, it’s this or nothing, either do this or your mangoes don’t go to the United States.

–Allan Mustard

So they were complaining to me that these mangoes, when they arrive in the United States, they cost $10 a piece, and they’re being undercut by the Mexican and Puerto Rican and Haitian mangoes. We sat down and did the cost calculation, and what we discovered was that if you took the cost of production, irradiation, including all the expenses related to irradiation, and transportation, including flying them from India all the way to New York City, it came out to $4 each. Importers were taking $6 of profit for every $10 that they sold a mango for.

The Indian diaspora wanted their Indian mangoes, they wanted this particular variety, the Alfonso mango, [and] some of the others that are very good, very tasty. So we went back, and we pointed out, well, this high cost is not all because of the expensive irradiation. Sixty percent of the cost is due to price gouging on the part of your importers on the other side, and one of the nasty little secrets about trade between the United States and India is that most of it is a family affair. You have a member of the family in the United States who is the receiver of the goods, collects the money, pays the shipper of the goods, who is a brother or cousin or some other relative, and that’s how the business is done. And if you were to reduce the price gouging, you would be able to sell at a lower price. Of course they didn’t want to hear that, didn’t want to get into that argument.

Evacuees wait to board U.S. military aircraft at Hamid Karzai International Airport, Kabul, Afghanistan, Aug. 23, 2021.

U.S. Marine Corps

2021

Reuniting Families of Afghans Fleeing Taliban Rule

Returning to the State Department out of retirement from a storied career, Ambassador A. Elizabeth “Beth” Jones took leadership of the office wrestling with the enormous challenges of assisting and relocating Afghan refugees after the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Kabul. She tells how her team reunited a family with a son they thought had died in the Abbey Gate suicide bombing.

It was one of the most difficult jobs most of us who worked on this have ever done. We were having to invent ways to do it and ways to overcome obstacles all the time. Every step of the way, we had in mind that we’re dealing with the lives of human beings who are potentially truly in danger. They’re having to make heartbreaking decisions about leaving family members behind if they were going to get out themselves. In addition, we were dealing with a huge number of unaccompanied minors who’d ended up in the U.S. in federal care. …

At one point, we were told that there was a 7-year-old boy in Kabul whose family had left, and we had to find his family. … He’d been with his family at a gate at the Kabul airport, that there was a huge explosion right next to him, and he then lost his family. He didn’t know what happened to his family. And he looked around, looked around, couldn’t find them, and finally decided he would walk home. … He went to his neighbor and said, “I don’t know where my family is.” …

Every step of the way, we had in mind that we’re dealing with the lives of human beings who are potentially truly in danger.

–Beth Jones

The explosion, of course, that he heard was the Abbey Gate explosion. The neighbor got hold of somebody in the AfghanEvac Coalition, who then called the liaison person, March Bishop, to say, “There’s this little boy who lost his family, and maybe that family is in the United States, and here’s his name.” So we were able to find the family at a base in Indiana. Our colleagues went to the family to say, Hamid says that he’s in Kabul and that you’re his family. And they said, “What?! … We thought he was killed in the explosion.”

The people talking to them said, “Do you have any evidence that this boy is your son?” Because there was a lot of concern about trafficking and that kind of thing. And they said, “Yes, we have his passport.” And they did, so they gave the passport to my colleagues on the base, who got the passport out to Doha for us, and we made arrangements for the little boy to be linked up with an Afghan family that were family members of an American citizen. Or I think the man himself, the American citizen, was there. And we linked Hamid up with him and had the Qataris take his passport in on the Qatar Air flight to Kabul so that he could show the Taliban—because the Taliban insisted everybody had a passport—that he had a passport, and eventually got him on a plane.