The State Department Dissent Channel: History and Impact

The Dissent Channel institutionalized dissent at the State Department a half century ago, but it is by no means the only way to register disagreement or propose policy alternatives.

BY SARA BERNDT AND HOLLY HOLZER

For more than 52 years, the Dissent Channel has endured as a mechanism for the workforce to express dissenting views in a privileged and confidential way to senior leadership at the State Department without fear of retaliation or exposure. The channel has become a cherished institution, serving as the primary example of the value that Secretaries of State have placed on dissent as a critical part of creating and implementing U.S. foreign policy. Upon learning about the Dissent Channel, other foreign ministries often express shock that the State Department has a formal way for its employees to disagree with the department’s policies and senior leaders. Some have minimized the Dissent Channel as lacking influence and rarely affecting foreign policy, or as a public relations tool for senior department officials to tout their open-mindedness.

The success of the Dissent Channel lies in its longevity and continued use, the dedication of the foreign policy community to its preservation and importance, and its broad influence on the policy process. Understanding the channel’s history, and seeing the kinds of messages received in the channel, affords us a chance to see why it matters and what makes for a strong dissent message.

A Short History

The Dissent Channel is an outgrowth of both the tumultuous politics of the Vietnam War and a period of institutional modernization. As protests against the Vietnam War grew across the U.S., newer officers—including those in the State Department, U.S. Agency for International Development, the U.S. Information Agency, and the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency—saw the impact that the war had on their generation. Under Secretary for Political Affairs George Ball’s views opposing U.S. involvement and escalation in Vietnam were the worst-kept secret in the State Department. Between 1965 and 1975, 39 Foreign Service officers were killed in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. Inevitably, these generational experiences shaped younger officers’ views on U.S. policy toward Vietnam and built the demand for a process for department personnel to express alternative and dissenting positions.

Simultaneously, the State Department was undergoing a larger reform effort. In 1967, as part of his efforts to modernize, Secretary of State Dean Rusk formalized the Open Forum, a volunteer association of younger officers whose mandate was to bring new or alternative views into the policy debate. And in January 1970, Under Secretary for Administration William Macomber launched a massive reform effort called “Diplomacy for the 70’s: A Program of Management Reform for the Department of State.”

Thirteen task forces staffed by more than 50 foreign policy professionals worked for more than five months. They produced more than 500 recommendations that were compiled in a 610-page volume delivered to Secretary of State William P. Rogers on Nov. 20, 1970. One of those recommendations was that the State Department “establish as a general principle [that officers] are free to submit a dissenting statement.” This opened the door for the creation of a formal mechanism for dissent.

Meanwhile, dissent bubbled. In November 1970, more than 50 Foreign Service officers signed a letter to Secretary Rogers outlining their opposition to the invasion of Cambodia. As the letter was circulated for additional signatures, it was leaked to the press. Incensed, President Richard Nixon called Under Secretary for Political Affairs U. Alexis Johnson in the middle of the night, demanding that the signers be fired immediately. They were not, but the pressure to silence them was intense.

The State Department established the right of foreign affairs officials to dissent in February 1971.

As a result of the space created by reform efforts and the courage of the dissenters of the time, the State Department established the right of foreign affairs officials to dissent in February 1971. A new section of the Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM), section 101, was called “Policy of Openness in Post Management.” According to Management Reform Bulletin No. 9 of Feb. 23, 1971: “Officers who may conclude, after carefully weighing all views, that they cannot concur in a report or recommendation are free to submit a dissenting statement without fear of pressure or penalty.” Although this bulletin has been seen as establishing the Dissent Channel, the term was not used. The new FAM section did not establish guidelines for who could dissent, to whom dissents should be communicated, or how the policy process should react to each “dissenting statement.”

In April 1971, Archer Blood, who was the consul in Dhaka (then in East Pakistan and now the capital of Bangladesh), was the first to test this new openness to dissent. Blood authorized the use of the consulate’s telegraph machine for seven staff at the consulate to send what is often called the first Dissent Channel message. The “Blood Telegram,” as it came to be known, appealed to the Nixon administration to intervene to stop the Pakistani military’s violence in East Pakistan. The dissent did not lead to U.S. policy change but did bring attention to what the dissenters called “genocide” in East Pakistan, generated support for their interpretation inside the State Department, and helped to create the Dissent Channel.

In late 1971 and early 1972, the Dissent Channel began to take shape as a formal mechanism. On Nov. 4, 1971, State Department cable No. 201473 laid out the first set of instructions for submitting dissenting opinions, emphasizing “that all expressions of dissent remain, at least in the first instance, in-house.” The Open Forum’s chairperson objected to these procedures because they did not require the department to act on dissents. The Open Forum asked for an action office to be designated that would distribute dissents to a small group of senior officials and respond to each dissent’s recommendations.

On April 8, 1972, according to the May 1972 Department of State Newsletter, the department officially created the Dissent Channel and outlined the process for submitting a dissent message. The Secretary’s Policy Planning Staff (S/P) was the office responsible for overseeing the Dissent Channel and acting on dissent messages—a role S/P continues to hold today. In 1971 and 1972, five Dissent Channel messages were sent to S/P.

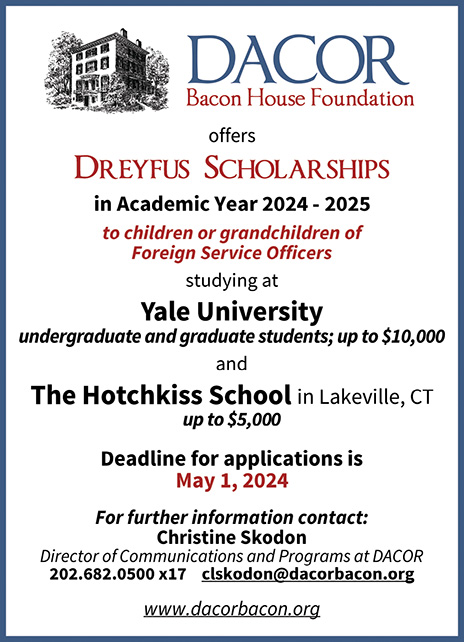

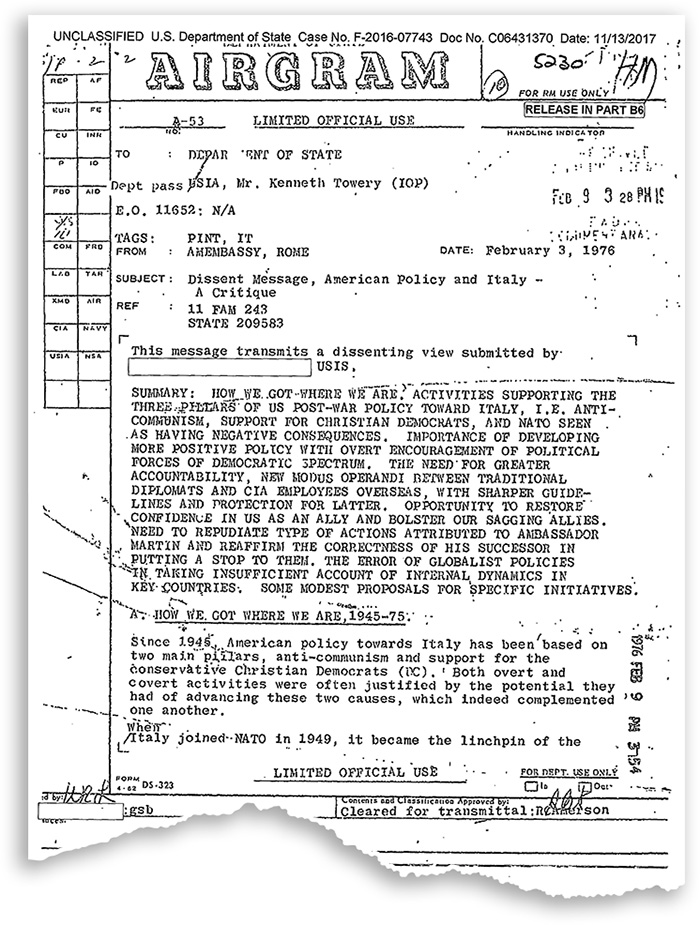

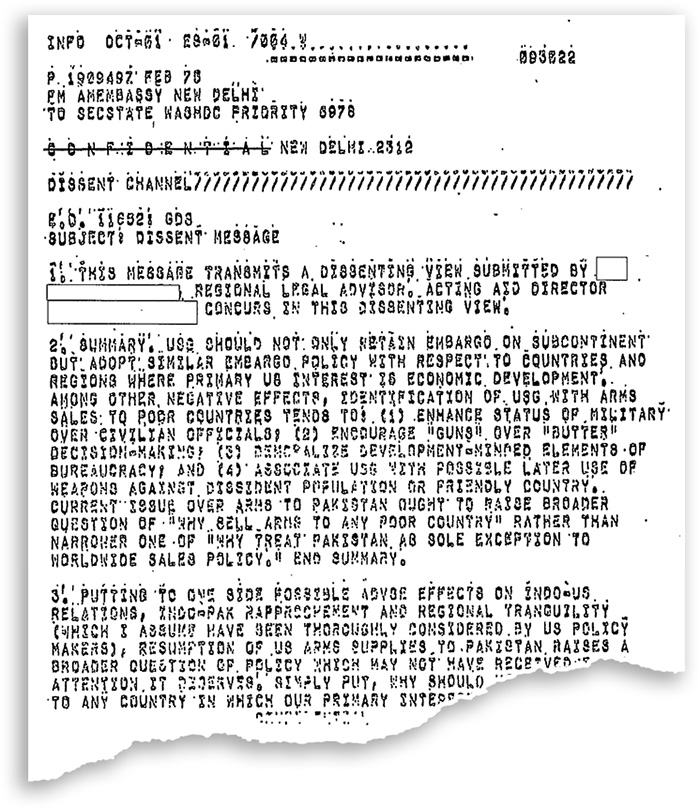

Informed and Thoughtful Analysis

Early, now-declassified dissents showcase the informed and thoughtful analysis that is essential to policymaking. Many of the first messages discussed U.S. policy in Southeast Asia, but dissenters also wrote about Somali influence in Ethiopia, Italian elections, the impact of assassinations on U.S. policy toward Chile under Pinochet, and U.S. arms sales to Pakistan. Many dissents were about evergreen topics such as how the U.S. should relate to authoritarian governments, how sanctions should be used, or how to engage with opposition groups abroad. Some dissents seem quite prescient in their analysis of, for instance, U.S. policy and the Mobutu regime in Zaire, the end of martial law in Poland, Soviet economic modernization, or the Rios Montt government in Guatemala.

Other early dissent messages covered management issues or raised concerns about waste, fraud, and abuse. Over the years, with the establishment of the Office of Inspector General in 1986, the passage of whistleblower protection laws, and other mechanisms for reporting fraud, abuse, and management problems, the Dissent Channel evolved to serve as a mechanism solely for dissent on foreign policy and its implementation.

Today, there are 404 Dissent Channel messages in the State Department’s retired holdings. Between 1972 and 2017, there were an average of almost nine messages per year sent to Washington, although a record 33 messages were sent in 1977. The retired Dissent Channel files remain classified and captioned, and they will be transferred to the National Archives. In response to an FOIA request, many of the older declassified Dissent Channel messages and responses from that set of files were properly declassified in 2018. These records, all of which are at least 35 years old, are available at foia.state.gov under Case # F-2016-07743.

The subjects of dissent messages reflect their times. During the first 20 years of the Dissent Channel, with authoritarians in power in much of the Americas and the U.S. deeply involved in Central America, Grenada, and Panama, messages from or about the Western Hemisphere made up a quarter of all dissents. In the 1990s, with NATO expansion and wars in the Balkans, messages about Europe made up more than a third of the dissents. At the same time, there were many proposals to reorganize the State Department amid post–Cold War funding cuts, so a relatively high percentage of dissents discussed issues related to department administration or reorganization. But messages on two mainstays of department business, bilateral relations and consular affairs, still composed a plurality of dissent messages during the 1990s.

The Dissent Channel is an outgrowth of both the tumultuous politics of the Vietnam War and a period of institutional modernization.

Recent dissents have instigated the development of new policies and the adaption of components of existing policy. They have also served as an impetus for bureau and office conversations on both leadership and dissent and how to dissent effectively (these are still classified and captioned).

Overall, Dissent Channel messages have generally fallen into three categories:

• Dissent or disagreement with policy, strategy, or goal, with a recommendation the department shift or change the overall policy.

• Disagreement with a particular action or policy implementation, often including an analysis that the department response or action is not strong enough (and the dissent is a call to action) or is too strong (and the dissent is a request to temper a policy).

• Appealing decisions that the dissenter either knows or believes have been made by senior leadership, and the dissent is a request for reconsideration before final action is taken.

The Value of the Dissent Channel

Policy professionals have often asked: Do Dissent Channel messages have an impact? In short, yes. Channel messages and their perspectives are often incorporated into ongoing policy discussions or serve as the impetus for a policy assessment or review, adding additional perspectives or a more complete assessment of potential consequences. Policies might be adapted, or timelines for implementation shifted. Dissent messages have served to open the doors for other stakeholders to join policy conversations and have moved bureau leadership to solicit alternative views within their teams and offices. Dissenters have been asked to meet with the Secretary or other senior officials to discuss their views, and in the early years, they were sometimes invited to discuss the issues at other internal venues.

Noteworthy also is that while strong dissents may not have “changed policy” in the moment, they have “influenced” how leaders thought about that same policy problem in later years. Outside commentators have even recommended that other agencies need dissent channels, too.

Secretaries of State have valued the channel as a tool for personnel to offer expert advice to the political leadership on issues central to U.S. foreign policy. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has repeatedly underscored the value he places on the right to dissent and the Dissent Channel. In 2021 testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he said: “This Dissent Channel is something that I place tremendous value and importance on. It is a way for people in the State Department to speak the truth, as they see it, to power. … I factored what I read and heard into my thinking and into my actions.” At the Foreign Service Institute in October 2021, he said: “I’m reading and responding to every dissent that comes through the Channel. And I hope the Dissent Channel will encourage a culture of constructive, professional dissent, more broadly throughout the department, because dissent makes us stronger.”

On Dissenting Well—The ABCD

Anticipate the counterargument. You need to know the issue well enough to be able to articulate the disagreement to what you are putting forward. Define the issue, provide data, identify gaps or needs, and know your audience.

Build curiosity, offer what is possible. Aim to create a space where people want to hear more, not set off their threat radar. Outline the potential consequences, and demonstrate previous efforts to address the issue.

Collect allies. Take the time to engage people one-on-one to build support. When you do this, you are showing respect to others and demonstrating that they are valuable to you.

Demonstrate your loyalty to the group. People often skip this step, but it is critical to show how your dissenting position is aligned with the mission and the group and to demonstrate that you are committed to the welfare of the team or institution.

—Holly Holzer

The channel is a valuable conduit of communication between senior leaders and the workforce at State. As former AFSA President Ambassador Eric Rubin wrote in the December 2022 FSJ: “Constructive internal dissent can lead to better policies, better ideas, higher morale, and a stronger United States if it is encouraged and taken seriously.” The continued practice of keeping Dissent Channel messages “in-house,” and requiring S/P to distribute them carefully and respond to them quickly, enables more honesty and candor. Leaking Dissent Channel messages undermines the value of the channel itself and potentially turns an apolitical policy tool into a political weapon, either against dissenters or against senior officials. Most drafters use the channel because they want to dissent confidentially and within the confines of the institution, to better inform department policy, and to influence the thinking of the Secretary.

An effective dissent is drafted not to give the dissenter the satisfaction of speaking out but rather to influence. With the audience being the Secretary, strong dissents offer straightforward analysis and propose alternatives. (Even the most experienced ambassadors and assistant secretaries pause before sending a direct message to the Secretary.) The messages demonstrate that the dissenter has worked to influence decision-making within the existing policy process and has tried to build consensus with other stakeholders, but that they believe the issue is so important that they must continue trying to convince senior officials, even when they’ve exhausted all their other options.

The Dissent Channel also serves as a symbol of the value and importance of dissent within the department. Every year AFSA offers four awards for constructive dissent by members of the Foreign Service. Many of the awards are given not for Dissent Channel messages (which AFSA does not receive) but for advocacy within the department to change an issue or policy or put forward alternative perspectives within our normal operations. Indeed, most of the dissent in the department happens routinely, in memos and meetings, in conversations and cables, and not in the Dissent Channel. This is as it should be, a part of our responsibility as diplomats and leaders.

At a recent Open Forum event on the Holocaust, one of the panelists asked: If there had been a Dissent Channel in the 1930s, would restrictive U.S. immigration policy toward Jewish refugees have been challenged or changed? We will never know, but the question gets to why the existence and use of the Dissent Channel remain important. For 52 years, the Dissent Channel has embodied the value placed on dissent by our institution and our leaders. Speaking truth to power with integrity and expertise is critical to the State Department’s role as the lead foreign affairs agency in the U.S. government, and integral to the ability of the U.S. to continue its primacy in world affairs.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Doing Dissent at State

All of us at the State Department have had a moment or moments in which we have said to ourselves, this policy is ineffective, is incorrect, or even likely to fail to achieve our goals. In those moments, many of us have asked ourselves how we should, or if we should, voice our position.

Philosophers have debated the meaning of dissent for centuries, often describing dissent as disagreeing with the sentiment of the majority. In the U.S., most Americans are familiar with the “dissenting opinions” written by Supreme Court justices. At the State Department, dissent can be understood as the act of putting forward a policy position that differs from current policy on an issue, country, or region. More than just a different opinion, it is the intentional presentation of an alternative or opposing approach to current or proposed policy that the dissenter determines will result in a better outcome for our foreign policy and national interest.

At State, the Dissent Channel is often put forward as the way to dissent. In reality, the Dissent Channel is only one of many ways to dissent at State, the one reserved for when other options have not succeeded or, in certain circumstances, where timing is of the essence. Dissent is and should continue to be part of our day-to-day work. U.S. foreign policy and programs are better and stronger if we are considering and examining the options, risks, and alternatives. Sometimes dissenting is easy, when it is part of an ongoing discussion where we are thinking through options. At other times it takes courage to put forward a position that contradicts or differs from current policy.

And when we dissent, it is important to consider why we are dissenting, when to dissent, and how to effectively dissent.

Why Dissent?

People are driven to dissent for multiple reasons—by personal conscience, a call to service, or a commitment to our institution and our mission. As public servants, we serve our nation and work to promote and protect the principles of democracy around the world. In this role, we have the responsibility to ensure our leadership and decision-makers have all of the information and context they need to make informed decisions. They rely on each of us to make sure that the consequences, risks, and impact of policy choices are debated and understood.

The presence of diverse voices and perspectives in a decision-making process is vitally important. Research has shown that a dissenting voice from the majority or popular position increases the intelligence of the group and improves the outcome. As a result of dissent, our institution and our policy are stronger and smarter.

When to Dissent?

When thinking about dissent, it is valuable to consider the issue, our values and mission, the other stakeholders or interest groups, and the risks you are willing to take. What is driving you—your integrity, the issue itself, the best interests of the United States? Personal integrity is a key motivator for dissent, but there is a fine line between acting out of personal integrity and being self-righteous and self-absorbed. You have to determine the risks and costs: Does the benefit of speaking out outweigh the cost of saying nothing?

To successfully dissent, you may need to expend your social capital and accept that initially your positions may be rejected. Ask yourself: Do you care more about the issue in this moment than you do about your own psychological welfare? Can you live with yourself if you say nothing? While dissenters often immediately experience rejection and negativity, in the long run others appreciate and are grateful for the dissent. Psychologist and George Mason Professor Todd Kashdan calls this the “sleeper effect” of dissent.

Dissent is and should continue to be part of our day-to-day work.

How to Dissent

Effective dissent is a combination of art and science. Timing, opportunity, precision, and persistence are key to it. Offer alternatives in meetings and policy discussions, question the “why” of a policy, look for the unintended consequences and raise those. Be specific, know your issue, present data and trends, put forward historical lessons. What is the impact of your proposal? How will it achieve our policy goals? What will it cost, and how long will it take?

Put your ideas out there through meetings and discussions or through the Policy Ideas Channel or the Open Forum. Build a community of the like-minded—make your proposal our proposal. Be ready for the opportunity when it is presented. Theories of change all consider the “windows of opportunity”—be on the lookout for your window.

You may not convince people during the first discussion, but if you assess it is important, find other opportunities to discuss it and keep refining your position and building allies. After you dissent and put your position up for a final decision, be willing to accept that you may not succeed. If you don’t, be prepared to implement a policy with which you disagree or choose other paths. State Department history is full of dissenters who implemented policies they fought against, as well as dissenters who found other portfolios to work on and dissenters who, when they could not implement, resigned.

Enabling Dissent

Each of us, no matter our rank in the State Department, will at some point lead a team or a process. Creating an environment where team members have the “courageous space” to come forward with differing perspectives and ideas results in better policy. To do this, we need to engage our team members and be curious about what they are thinking or how they are approaching an issue and, importantly, express our appreciation for their perspective when they do share. Some people will easily speak out in a meeting; you may need to approach others and ask one-on-one what they think about an issue.

As the leader, ask your team’s perspective first before sharing your own when discussing an issue. Ask the team what the consequences of a policy are, what the risks are, and what will and won’t be accomplished. Ask the team how bilateral and multilateral partners will respond to the idea, what their criticisms are, and whether they are valid. Ask the team to question their assumptions: Do you still assess that our reasons for action hold? Has the context changed, or have priorities shifted?

—Holly Holzer

Dissent Channel

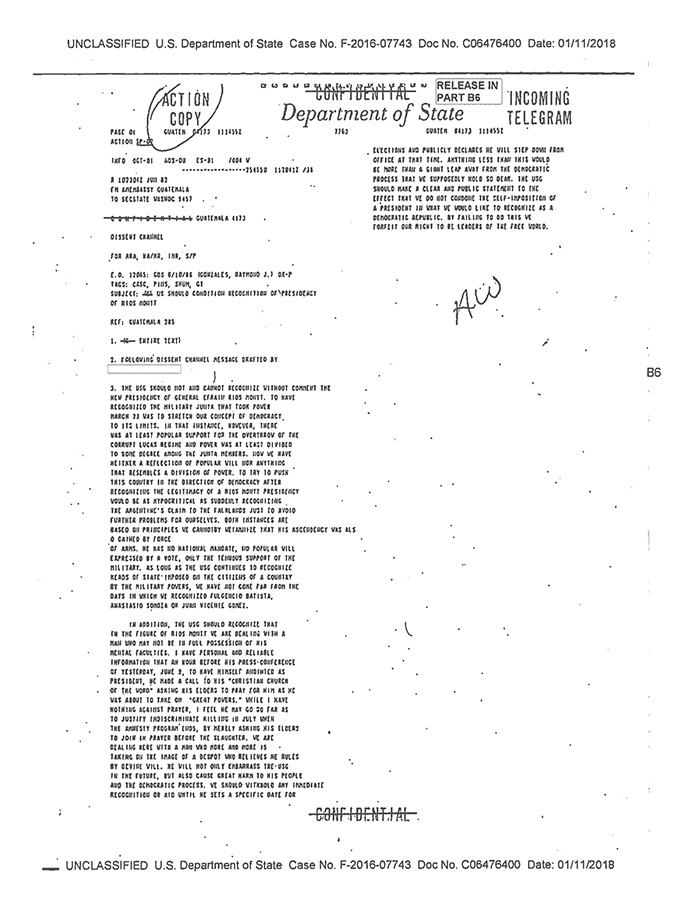

June 10, 1982

Subject: US Should Condition Recognition of Presidency of Rios Montt

… The USG should not and cannot recognize without comment the new presidency of General Rios Montt. To have recognized the military junta that took power on March 23 was to stretch our concept of democracy to its limits. In the instance, however, there was at least popular support for the overthrow of the corrupt Lucas regime, and power was at least divided to some degree among the junta members. Now we have neither a reflection of popular will nor anything that resembles a division of power. To try to push this country in the direction of democracy after recognizing the legitimacy of a Rios Montt presidency would be as hypocritical as suddenly recognizing the Argentine’s claim to the Falklands just to avoid further problems for ourselves. … He has no national mandate, no popular will expressed by a vote, only the tenuous support of the military. As long as the USG continues to recognize heads of state imposed on the citizens of a country by the military powers, we have not gone far from the days in which we recognized Fulgencio Batista, Anastasio Somoza or Juan Vicente Gomez. … We should withhold any immediate recognition or aid until he sets a specific date for elections and publicly declares he will step down from office at that time.

Dissent Channel

June 2, 1978

Drafter Desires Distribution to P, AF and EA

Subject: Recommendation for US Policy Towards Zaire

SUMMARY: The degree of corruption and ineptitude of the Mobutu regime has reached the point where integral reform is for all practical purposes impossible—witness the lack of implementation of the reforms announced by Mobutu in July 1977 after the first Shaba War and related reforms promised on even earlier occasions. All available evidence indicates that Mobutu will find a way to sabotage externally imposed reforms which threaten to reduce his power and financial prerogatives. The inescapable conclusion is that Mobutu will not be able to reverse the decline of his political fortunes, and that his regime will, sooner or later, be overthrown. The longer Mobutu hangs on, the greater the danger of a revolutionary upheaval giving rise to a radical anti-US regime along Angolan, Ethiopian, or Cuban lines. There are only two realistic options available to the US to counter this growing threat to our interests in Zaire: (1) to concert with Belgium and France to remove Mobutu from power; (2) to reduce substantially our presence here, if Belgium and France refuse to cooperate, in order to increase the likelihood of our being able to establish good working relations with the successor regime.

This dissent, prepared by political counselor XXXXX, argues that we should seek the first alternative, while being prepared to fall back on the second if the Belgians and French refuse to cooperate. END SUMMARY

Read More...

- “Loyalty and Dissent: The Foreign Service and the War in Southeast Asia” by Daniel A. Strasser, The Foreign Service Journal, December 1992

- “The Agony of Dissent,” Interview with Stephen Walker, Marshall Harris, and George Kenney, The Foreign Service Journal, November 1993

- “The Role of Dissent: In National Security, Law and Conscience” by Ann Wright, The Foreign Service Journal, July-August 2013

- “Celebrating—and Strengthening—Constructive Dissent” by Eric Rubin, The Foreign Service Journal, December 2022