2023 Award for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy: A Conversation with Ambassador John Tefft

U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs Daniel Fried (front second from left) and U.S. Ambassador to Georgia John Tefft (right) visit a checkpoint, Akhmaji, near the Russian-backed separatist region of South Ossetia, which had broken away from Georgia, on Oct. 19, 2008. The visit came amid persistent tension along the edges of the breakaway region at the heart of the August war between Georgia and Russia.

AP Photo / Shakh Aivazov, Pool

Ambassador John F. Tefft, a four-time chief of mission who specialized in Russian and Eurasian affairs and played a critical role in the peaceful transition of the post-Soviet space, a leader revered for his professionalism, and mentor to several generations of diplomats during his more than 45-year Foreign Service career, is this year’s recipient of the American Foreign Service Association’s Award for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy. (For coverage of the Oct. 5 ceremony, see AFSA News, page 63.)

Tefft is the 29th recipient of this prestigious award, given annually in recognition of a distinguished practitioner’s career and enduring devotion to diplomacy. Past honorees include George H.W. Bush, Thomas Pickering, Ruth A. Davis, George Shultz, Richard Lugar, Joan Clark, Ronald Neumann, Sam Nunn, Rozanne Ridgway, Nancy Powell, Thomas Boyatt, William Harrop, Herman “Hank” Cohen, Edward Perkins, John D. Negroponte, and Anne Patterson.

Ambassador Tefft joined the Foreign Service in 1972. Early assignments included Jerusalem, Budapest, and Rome, but most of his distinguished career focused on Russian and Eurasian affairs. As deputy director in the Office of Soviet Affairs from 1989 to 1992, he was at the center of Washington’s efforts to deal with historic transitions from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the end of the Soviet Union. As deputy chief of mission in Moscow from 1996 to 1999 (and chargé d’affaires from November 1996 to September 1997), he managed one of our largest missions and most important relationships.

Appointed by President Bill Clinton to serve as U.S. ambassador to Lithuania (2000-2003), he worked successfully to have Lithuania admitted to NATO. He served as the international affairs adviser at the National War College in Washington, D.C., from 2003 to 2004, when he was named deputy assistant secretary of State for European and Eurasian affairs responsible for U.S. relations with Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova.

In 2005 he returned overseas as U.S. ambassador to Georgia (2005-2009), leading the embassy during the 2008 Russo-Georgian war and U.S. efforts to assist Georgia’s recovery from the war. Amb. Tefft was then named U.S. ambassador to Ukraine (2009-2013).

Amb. Tefft originally retired from the Foreign Service in September 2013 and served as executive director of the RAND Corporation’s U.S.-Russia Business Leaders Forum from October 2013 to August 2014, when he was recalled to duty as U.S. ambassador to the Russian Federation (2014-2017). There he navigated the strained relationship between the U.S. and Russia following the Russian invasion and annexation of Crimea.

Throughout his career, Amb. Tefft has received numerous awards. Among them are the Secretary of State’s Distinguished Service Award in 2017, the State Department’s Distinguished Honor Award in 1992, the Deputy Chief of Mission of the Year Award for his service in Moscow in 1999, and the Diplomacy for Human Rights Award in 2013. He received Presidential Meritorious Service Awards in 2001 and 2005.

Amb. Tefft holds a B.A. degree from Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and an M.S. from Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. He is married to Mariella Cellitti Tefft, a biostatistician and nurse who served with him at each of his Foreign Service assignments and contributed greatly to their joint effort to represent the United States. They have two daughters, Christine and Cathleen, who both live and work in the Washington, D.C., area, and two granddaughters.

Editor in Chief Shawn Dorman conducted this interview with Ambassador Tefft in October.

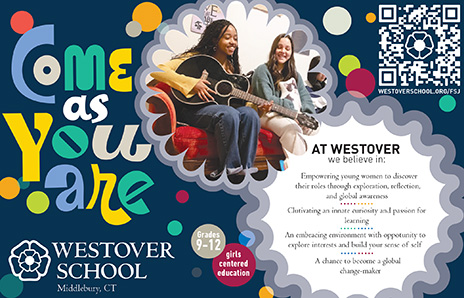

U.S. Ambassador to Russia John Tefft (left) and Secretary of State John Kerry greet President Vladimir Putin at the Bocherov Ruche—a government villa—in Sochi, Russia, before a bilateral meeting on May 12, 2015.

U.S. Department of State

Joining the Foreign Service

FSJ: What led you to a career in diplomacy?

Ambassador John F. Tefft: As I entered my senior year at Marquette University in 1970, I was looking at a variety of future options, including studying for a Ph.D. in history, teaching history in secondary school, and seeking a position in government service. I had long been interested in international affairs, and applied for the Foreign Service. I surprised myself by passing all the exams. I was offered a position in the fall of 1971 and accepted. I was sworn in on Jan. 6, 1972.

FSJ: What was notable about joining the Foreign Service in the early 1970s? What do you recall about the orientation and training from that time?

JFT: The Foreign Service was coming off a period in which many officers were sent to the Civil Operations and Revolutionary/Rural Development Support (CORDS) program in Vietnam; this was a rural pacification and development initiative. My Foreign Service class was the first in many years that did not have officers assigned to CORDS. My life began at the Foreign Service Institute, which was then located in a high-rise building in Rosslyn. I took the A-100 course with 14 other officers; the State Department had a very restricted budget in those days, so we had one of the smallest classes in Foreign Service history. My wife, Mariella, took the “Wives’ Course,” as it was then called. I was young and inexperienced, so everything was new to me. But I was excited about a career in government service.

When the assignments for our class came out, I was slotted for a rotational position at our consulate general in Jerusalem. It was a great first assignment, as I spent about half my time in the consular section, and the remainder doing some political and economic reporting on Jerusalem and the West Bank, which made up our consular district. This gave me a broad perspective on the work of the Foreign Service. The big event during our tour was the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, and subsequently Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy, which we supported.

FSJ: You were a career Foreign Service officer for more than 45 years, including service in real hot spots. What kept you in the Service for that long?

JFT: I found the Foreign Service fascinating from the very start. My experience in Jerusalem had a big impact on me. It gave me a chance to see history being made right before my eyes. I had some wonderful bosses and mentors over the years. I was also fortunate to continue to get good assignments. I ended up feeling that this was a career for which I had the right personality and skills. I never really thought of another career. And I had the wonderful support of my wife, Mariella, throughout my career. She was my partner in the Foreign Service for 45 years.

On Dealing with Russia

John and Mariella Tefft (right) with former Ukranian President Viktor Yushchenko and his wife, Katya, after a dinner at the Yushchenko residence in 2012. From left: Stanford University Professor Larry Diamond; President Yushchenko; Katya Yushchenko; Christine Tefft, the ambassador’s daughter; Ambassador Tefft; and Mariella Tefft.

Courtesy of John Tefft

FSJ: Much of your career was spent in the Soviet Union and then Russia and the countries that had been part of the USSR. What sparked your interest in this region?

JFT: When I was a senior at Edgewood High School in Madison, Wisconsin, I took an elective course in Russian history. Sister Marie Michel, our teacher, not only taught us the main political and economic developments in Russia but also Russia’s cultural achievements. She took us to see the opera, “Boris Godunov,” at the Lyric Opera in Chicago. She had prepared us by teaching us about the “Time of Troubles” and about Mussorgsky’s opera. She played records with the most famous arias and gave us English-language librettos to follow along. It was a phenomenal experience, a wonderful introduction to Russian culture.

That same year, in 1965, David Lean’s film, “Dr. Zhivago,” was released. It captivated me. It was a visual introduction to Russia’s history, capturing the trauma of the Bolshevik Revolution and its aftermath through an exploration of the memorable characters in Boris Pasternak’s novel. Russia was in my imagination now as it never had been before.

FSJ: After “retiring” from the Foreign Service in 2013, you were called back in 2014 to be the U.S. ambassador to Russia, which had just annexed Crimea a few months before. At the time, Ambassador (ret.) Steven Pifer said this to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: “I can’t think of a better choice for the embassy in Moscow. … He knows how to deliver a tough message in a way the recipient may not like the message but doesn’t want to shoot the messenger.” How do you do that?

JFT: That was a wonderful compliment from Steve, one of the very best diplomats I ever worked with. Throughout my career, I always tried to be as professional as possible. For me and my staff, the situation in Moscow in 2014 placed a high premium on the need for professionalism. I had no illusions about the new assignment. I knew that we were in for a tough time. Our relationship had been strained before the Crimean invasion. Now it was nearly frozen.

We were often harassed, and we were attacked in the Russian press. I tried to convey messages, both official and personal, in a candid but transparent manner. The same was true in our interactions with Russian media. There was a lot of emotion and anger that the U.S. did not just accept what the Russians thought was their right, not to mention the sanctions we had imposed on Russia.

FSJ: During that period, the Russian Foreign Ministry ordered the U.S. to cut down staff significantly, leading to closure of consulates and the departure of many staff, both U.S. diplomats and locally employed staff. This must have been so hard. How did you manage this and keep the embassy functioning?

JFT: Right at the end of my assignment, the Russian Foreign Ministry ordered us to reduce our staff at the embassy and at the three consulates general in St. Petersburg, Yekaterinburg, and Vladivostok to the same level of personnel at the Russian embassy and consulates in the U.S. The Russians did not employ Americans at their facilities, but we did have many Russian employees, so the cuts were severe. This new draconian Russian order forced us to cut nearly two-thirds of our staff. Subsequent ordered cuts reduced our staff even more and forced the closing of our consulates general.

Our new deputy chief of mission (DCM), Anthony Godfrey, did a masterful job working with the section chiefs and agency heads, laying out a clear set of embassy objectives and needs, and then deciding which employees we needed to keep to meet those criteria. The choices we had to make were difficult and traumatic for American and Russian employees alike. Officers who had just arrived were asked to go home, while others who were in training in Washington had their assignments canceled. Many of our Russian staff were let go. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson authorized a generous severance package of one-half year of salary and health benefits for our Russian employees. Some of the employees went to work with Russian firms, which then provided contracted custodial and other services to the embassy. They were able to continue working. For many others, it was a sudden and tragic end to their career at the U.S. embassy.

We had a number of town hall meetings where I tried to explain the rationale behind the difficult choices we had to make. I emphasized that we did not want this outcome but had no choice. I will always remember a conversation at the end of one of those town halls with one of the Russian employees who had worked in our public affairs section for 18 years processing the numerous international visitors we sent to the U.S. She told me she was sorry to hear that she was being let go. She said she appreciated our effort to explain candidly how we had come to making the difficult decisions on personnel. She said that working for the American embassy had been the greatest experience of her life and thanked me. I had tears in my eyes as she gave me a hug and said goodbye.

The situation in Moscow in 2014 placed a high premium on the need for professionalism. I had no illusions—I knew that we were in for a tough time.

FSJ: What advice would you have for today’s ambassador to Moscow on dealing with the Russian government?

JFT: I don’t need to give Ambassador Lynne Tracy any advice. She is enormously qualified and has a long background of service in Moscow and at difficult Foreign Service posts. Amb. Tracy was my deputy when I was ambassador, and she was intimately involved in every aspect of our diplomacy with Russia. She ran the embassy brilliantly and has a wealth of knowledge about Russia and our relationship with Russia. I thought she was an ideal choice to be our ambassador at such a difficult time in our bilateral relationship. She epitomizes the professionalism I spoke about earlier.

FSJ: Early in your career you had experience working with Moscow on the delegation to the START arms control negotiations leading to a successful agreement that held for decades. New START, now the only remaining nuclear weapons treaty between the U.S. and Russia, was set to expire in 2021, but the two sides agreed to extend it for five years. However, in February, President Putin said Russia was “suspending its participation.” Do you have any hope for Russia to return to the agreement? What might it take to restart arms control cooperation between the U.S. and Russia?

JFT: I served for about a month with the State Department team at the START negotiations in 1985. It was a great experience, sitting across the negotiating table from the Soviet group. I learned a lot about arms control and the process through which we and the Soviets tried to find negotiated compromises to some of the thorniest and most technologically complex issues.

I think that we will have to wait and see how the Russian war in Ukraine transpires before we can know with any confidence whether Russia will return to compliance with New START and how they will proceed on nuclear arms control in the future. With the war having a serious impact on Russian finances, I do not think the Kremlin wants to get into any new arms race. We also have to remember that the clock is ticking; New START will expire in 2026 and cannot be renewed.

FSJ: In the late 1990s you served as DCM and chargé at Embassy Moscow. How would you compare that to your time as ambassador there in 2014 to 2017?

JFT: They were two very different periods in the history of our bilateral relationship. President Boris Yeltsin still ruled in the late 1990s when I was DCM. We had a broad-based bilateral relationship, featuring visits by President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore. Gore headed a bilateral commission with Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin that met every six months or so. Cabinet members and ministers in a variety of fields met regularly to shepherd many different bilateral initiatives. At the embassy, we had wide access to Russian officials and to the Russian people across the country.

Later, my three years as ambassador were marked by serious strains in the relationship caused by Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea and subversion of the Donbas in 2014. Western sanctions had begun to hurt the Russian economy. The Russian government could not impose economic sanctions on us, so they took it out on the embassy. We had our access to officials limited and were harassed regularly. We tried to preserve our people-to-people programs. I and my staff traveled around the country. We worked hard to get our message out to the people of Russia but were constantly attacked by a withering Russian propaganda onslaught blaming the U.S. for nearly everything.

With the war having a serious impact on Russian finances, I do not think the Kremlin wants to get into any new arms race.

FSJ: You are the only U.S. FSO to have served as both ambassador to Russia and to Ukraine. Are there particular insights you gained from this unique experience that might inform policymakers today?

JFT: I wrote an article for The Foreign Service Journal in March 2020 in which I reflected on the course of Russia and Ukraine in the post-Soviet period and the challenges it presented for the United States. I think most of my judgments in that article remain pretty sound, although back then no one predicted that Putin would make the strategic mistake of an allout invasion of Ukraine with his February 2022 attack.

I think we will continue to need strong bipartisan support for our Ukraine policy. We are at a seminal inflection point in Europe now, as President Biden has frequently said. The results of this war and the security structure that emerges from this conflict will profoundly affect the region and American foreign policy for years to come. The conflict in Ukraine will have a serious impact on our country and our foreign policy. This conflict cannot be ignored any more than the Hamas attack on Israel can be ignored. The United States is still the leader in defending the world from aggression and terrorism. We cannot retreat into an isolationist shell and pretend otherwise.

FSJ: How can our diplomats rebuild the relationship with Russia after Putin?

JFT: This is really an impossible question to answer right now. We do not know how the Russian war on Ukraine will turn out, and it is hard to estimate today what lasting changes will occur in Russia as a result of the war. We need to help Ukraine defeat Russian aggression, and then help build a new, more stable order, which will restore and preserve Ukraine’s independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity.

There is good work going on outside the government now in think tanks and among Russian experts, trying to scope out what our priorities need to be. Clearly, we will need to address the control of nuclear weapons as the New START treaty comes to an end in 2026. That will not be easy with all the new weapons and technologies being developed. And China is rapidly building up its nuclear arsenal. I suspect we will have a broader struggle to rebuild the international order, with Russia partnering with China in opposing democracy and promoting an authoritarian world.

Ambassador John Tefft and his wife, Mariella, meet with former President of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev at the Gorbachev Foundation on Oct. 12, 2016. From left: Ambassador Tefft, Mariella Tefft, U.S. Political Minister Counselor Anthony Godfrey, and President Gorbachev.

Courtesy of John Tefft

Other Postings

Ambassador John Tefft and his wife, Mariella, had lunch with former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (center) at the ambassador’s residence in Kyiv on June 24, 2012.

Courtesy of John Tefft

FSJ: You served as ambassador in Lithuania from 2000 to 2003. Today, some 20 years later, what’s the biggest change you see there? What was the highlight of your time as ambassador and what was the biggest challenge?

JFT: The most important development during my ambassadorship, and one on which I and my staff worked hard, was Lithuania’s selection to be a member of NATO. Along with membership in the E.U., NATO has transformed the Baltic states. I was very impressed with what the Lithuanians have achieved politically and economically when I visited Vilnius in September. Lithuania is a success story, an advertisement for what democracy and a market economy can achieve. I am proud that the United States has supported Lithuania every step of the way.

FSJ: You were ambassador to Georgia in 2008 when Russia invaded over the disputed areas of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Did the embassy see that coming?

JFT: It was clear to us that Russia was intent on trying to bring Georgia to heel and block membership in NATO and, more broadly, Western integration. The Russians sent more troops into Abkhazia and South Ossetia in the first half of 2008, and the United States and the E.U. worked hard to support a negotiated solution. Most saw Abkhazia as the likely potential flash point. In the end, the conflict was set off in South Ossetia.

When war broke out, it quickly became clear that Russia wanted to oust Georgia’s democratically elected government. The U.S. rallied to the support of Georgia. Our $1 billion assistance package after the war ended helped the Georgians deal with their humanitarian crisis, stabilize their economy, and rebuild their country.

Our American and Georgian staff did a tremendous job during the very tense days of the war and in implementing the assistance package. There was a lot of fear in the first few days. It peaked the night Russian forces broke through Georgian lines and advanced on Tbilisi. We offered our American dependents voluntary departure to Yerevan, where Ambassador Masha Yovanovitch and her staff hosted them until the fighting ended. Many of our Georgian staff had loved ones and friends caught up in the fighting. I tried to share with them every day what I knew and tried to console them as the fighting raged.

FSJ: Before that crisis, what opportunities and challenges did you face in Georgia?

JFT: People often forget about the substantial progress Georgia made in reforming its economy and fighting corruption in the years before the war. A Russian expert on economic reform once told me that Georgia did more than any other post-Soviet nation to reform itself. Through our USAID programs, we contributed financing and expertise to help the Georgians design and implement the reform programs.

The United States is still the leader in defending the world from aggression and terrorism. We cannot retreat into an isolationist shell and pretend otherwise.

FSJ: You were ambassador to Ukraine during another time of tension with Russia (2009-2013). Can you tell us what that was like, and what were the primary achievements in the U.S.-Ukraine relationship?

JFT: Early in my assignment, Viktor Yanukovych was elected president of Ukraine. We tried to work with his government, and we had some success. Ukraine, for example, gave up more than 100 kilos of highly enriched uranium as part of the Obama administration’s program to improve nuclear security in the world.

Over time, however, Yanukovych and his “family” grew more corrupt and steadily estranged themselves from the Ukrainian people. Civil society was getting stronger in Ukraine, and the U.S. and Europe supported the development of civil society. By the time I left Ukraine in July 2013, Yanukovych’s support had fallen below 20 percent. In November, under pressure from Putin, he abandoned the association agreement that Ukraine had been negotiating with the E.U. Demonstrations broke out on the Maidan Square in Kyiv, and we all know what happened after that.

FSJ: Any advice for the U.S. ambassador in Kyiv today, during the continuing assault from Russia?

JFT: Bridget Brink, our ambassador in Kyiv now, is a superb Foreign Service officer. She was our political counselor in Georgia during my time there and did a great job. From my observations, she is doing very well leading our embassy in Kyiv in very dangerous conditions.

John and Mariella Tefft make a winter visit to the Yasnaya Polyana Estate of Leo Tolstoy (with his grave in the background) in 2016. From left: Ambassador Tefft; Dr. Galina Alekseeva, director of research at the estate; and Mariella Tefft.

Courtesy of John Tefft

On Being “The Best Boss”

FSJ: You are being honored with the lifetime award in part because of how you mentored multiple generations of diplomats. Many who have worked for you refer to you as the best boss they’ve ever had. What’s your secret?

JFT: I am not sure there is any secret. I always tried to treat the people with whom I worked the way I wanted to be treated when I was a younger officer. Foreign Service professionals want to be treated with respect and openness. They want to know that their work is valued and that they are contributing to our foreign policy goals. I have always tried to make sure that each member of my staff understood that I valued their work. I have always written recommendations for my staff and continue to do so today six years into retirement.

I have always found former Secretary of State Colin Powell’s 13 rules of leadership to be a good practical guide. They are:

Former U.S. ambassadors to Russia (from left) John Tefft, Alexander “Sandy” Vershbow, John Beyrle, and William “Bill” Burns, at a dinner hosted in their honor by former Ambassador-at-Large for Global Women’s Issues Melanne Verveer at her home on Jan. 13, 2018.

Courtesy of John Tefft

- It ain’t as bad as you think! It will look better in the morning.

- Get mad; then get over it.

- Avoid having your ego so close to your position that when your position falls, your ego goes with it.

- It can be done.

- Be careful what you choose. You may get it.

- Don’t let adverse facts stand in the way of a good decision.

- You can’t make someone else’s choices. You shouldn’t let someone else make yours.

- Check small things.

- Share credit.

- Remain calm. Be kind.

- Have a vision. Be demanding.

- Don’t take counsel of your fears or naysayers.

- Perpetual optimism is a force multiplier.

FSJ: What qualities make for a good leader and a good manager, and what advice do you have for others in leadership positions?

JFT: On his 100th birthday, Dec. 13, 2020, former Secretary of State George Shultz wrote an opinion piece for The Washington Post titled “The 10 most important things I’ve learned about trust over my 100 years.” It had some excellent advice for leaders.

Shultz reflected on his century of life and long years of public service, saying: “I’m struck that there is one lesson I learned early and then relearned over and over: Trust is the coin of the realm. When trust was in the room, whatever room that was—the family room, the schoolroom, the locker room, the office room, the government room, or the military room—good things happened. When trust was not in the room, good things did not happen. Everything else is details. ...

“‘In God we trust.’ Yes, and when we are at our best, we also trust in each other. Trust is fundamental, reciprocal and, ideally, pervasive. If it is present, anything is possible. If it is absent, nothing is possible. The best leaders trust their followers with the truth, and you know what happens as a result? Their followers trust them back. With that bond, they can do big, hard things together, changing the world for the better.” It is hard for me to come up with better advice for leaders. And Secretary Shultz proved it by the success he had in serving our country in multiple high-level positions. You have to work hard every day to build trust and invest in those who work for you.

AFSA and Dissent

FSJ: When did you join AFSA, and what convinced you to join?

JFT: If my memory serves, I joined right after I entered the Foreign Service. I joined because I felt that we needed an organization to represent the interests of all the members of the Foreign Service. We needed an organization to speak for the Foreign Service as a whole and to represent individual members when they needed guidance or help in resolving disputes with management.

FSJ: In your view, how and where can AFSA add the most value?

JFT: I have seen firsthand how AFSA has helped its members over and over during my career. At the recent AFSA awards ceremony, I was so pleased to learn of AFSA’s support for initiatives dealing with disabled children of FSOs. And AFSA raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to cover the legal expenses of officers who were caught up in the Trump administration scandal over Ukraine. These and many other initiatives show just how important AFSA is and how it has responded to the needs of individual officers and the Service as a whole.

FSJ: As you know, AFSA also honors dissent within the system through its annual awards. What has been your experience with dissent? Any advice for colleagues on whether, when, and how to speak up if they disagree with a policy?

JFT: I have always thought AFSA’s support for dissent through its annual awards was a critical component of AFSA’s mission. I tried in the embassies I led to encourage anyone with alternative views about our policy or the direction of our mission to come forward and tell me and the DCM. I thought it best to have a healthy internal discussion. We could then fix the problems at post and/or share with the department alternative views on how to deal with the situation we confronted in the country to which we were assigned.

Ambassador John Tefft and Mariella Tefft at the State Department for the AFSA awards ceremony, where he received the award for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy on Oct. 5, 2023.

AFSA / Caleb Schlabach

Perspectives on Diplomacy

FSJ: What are the essential ingredients for a successful diplomat?

JFT: I don’t think there is one specific model for a successful diplomat. The Foreign Service is a very diverse group of personalities, and overall we are enhanced by that mix. Clearly, the best FSOs are empathetic and adept in social situations. They love to represent their country and the American people in foreign countries. They are practical problem-solvers and need to be good negotiators. I was very fortunate as my career developed to have had some extraordinary mentors and bosses. Among them were Tom Simons, Lynn Pascoe, Jim Collins, Roz Ridgway, Sandy Vershbow, Larry Napper, Beth Jones, and Tom Pickering.

FSJ: As you know, the Foreign Service reaches its centennial in 2024. What would you say will be the top three issues for American diplomacy in the coming years?

JFT: I think the United States faces a vast array of new challenges. The international order which we have known since World War II is now being seriously challenged by China and Russia. They are promoting authoritarianism over democracy. We see resurgent attempts at imperial-style domination instead of respect for sovereign independent states. International security has been challenged. War, terror, and instability afflict our world, as we see in Ukraine, the Middle East, and Africa. President Putin has stopped complying with the New START treaty, and both Russia and China are expanding their nuclear arsenals and developing new technologies for delivering nuclear weapons. We cannot manage this alone; we need strong alliances and effective multilateral diplomacy to achieve our national goals.

We will also have to confront a number of existential threats to our world. Climate change is already wreaking havoc in many ways around the world. Artificial intelligence will transform every aspect of life. COVID-19 has taught us the threat posed by pandemics. It is really a staggering list of issues that our country and new generations of the U.S. Foreign Service will have to confront. There is, by the way, an excellent new book by Andrew Hoehn and Thom Shanker, Age of Danger, which provides a very readable survey of the array of challenges and threats we face.

FSJ: What is your advice to current members of the Foreign Service who may be considering leaving the Service?

JFT: Everyone considering leaving the Service has their own reasons. Sometimes it is policy; sometimes it is family or other personal issues; and sometimes it is because the individual does not feel they are achieving what they’re capable of in the Foreign Service. This is why mentorship is so important. Every officer needs to feel that they can discuss their problems, their needs, and their future with a sympathetic boss or mentor.

People often forget about the substantial progress Georgia made in reforming its economy and fighting corruption in the years before the war.

FSJ: Do you recommend a career in the Foreign Service to young people today? Why or why not?

JFT: Yes, absolutely. I think it is a wonderful career. That said, I tell university audiences that individuals considering a Foreign Service career should look at all aspects of the career before they make the decision: living abroad away from family for long periods, serving in danger posts or in unaccompanied assignments, the impact of Foreign Service on the life and career of a spouse or partner, having and raising kids in the Foreign Service. There are more. I try to make sure that young people considering this career go in with their eyes as wide open as possible.

FSJ: Are you optimistic about the future of professional diplomacy? Why or why not?

JFT: Yes. As I said in my acceptance speech for the Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy Award: “It seems to me that the need for a Foreign Service of creative, nonpartisan professionals advising our political leaders and implementing American foreign policy around the world is as vital today as any time in my lifetime. Understanding the threats we face and devising creative strategies and tactics to deal with them will be vital. That will require hard and soft power. And we will have to do this with our own country still deeply divided. Like Masha Yovanovitch and so many others, today’s Foreign Service officers will have to stand up for our country’s values and their personal integrity as they do their work.”

FSJ: Is the Foreign Service as an institution strong today?

JFT: I think the Foreign Service went through a tough time with the last administration. This is not the first time in our history that we have experienced setbacks. But I think we are getting stronger. The younger officers whom I have met are very talented. During my recent visit to Lithuania, I was impressed with the talent and performance of younger officers. We need to keep building the young talent we have recruited. We need to mentor and nurture their careers.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.