Taking on Family Member Employment. Really!

Family member employment is a critical issue for members of the U.S. Foreign Service. The State Department finally seems to be taking it seriously.

BY DEBRA BLOME

For eligible family members (EFMs) in the Foreign Service, the process of finding employment isn’t easy and never has been. The reasons are obvious: frequent moves, language barriers and limited options, to name just a few.

But what is new is that the Foreign Service has now tasked itself with really doing something about it.

Compare how the issue was treated in the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development’s Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review. The first-ever QDDR, released in 2010, devoted an entire chapter to “Working Smarter”—without ever mentioning family member employment. The new QDDR, released in April 2015, discusses expanding opportunities for family member employment as part of the section titled “Adapting our Organizations to Take Care of Our People.”

“Two-career families are increasingly the norm in both American society and in the Foreign Service,” the report states. “This means that ensuring opportunities for spousal employment should be an integral part of our plans to retain and motivate staff.”

The report says State and USAID will strengthen efforts to build EFM career tracks, use EFMs to fill existing staffing gaps when possible, and create a database of EFM skills to help spouses find jobs both at post and in Washington. It also pledges that State and USAID will expand programs already in existence, and will “pursue mechanisms” to facilitate the security clearance process, so EFMs can begin work at post without a “lengthy” delay.

(Though the QDDR document is a product of State and USAID, the EFM policies and reforms it calls for apply to employees of all the foreign affairs agencies under chief-of-mission authority on an assignment abroad.)

A Big Deal

For AFSA, family member employment is a major advocacy issue. State Vice President Angie Bryan says she addresses the topic in her meetings with all relevant offices within the department. She wants State to understand that the issue is critical “not just to the spouses or to the family members, but also to the employees.”

She thinks they’re getting the message. “I must say that I do think the department is taking it seriously,” Bryan says.

For the State Department’s Family Liaison Office—which is charged with improving the quality of life for all employees and family members—family member employment has always been a big issue. “Expectations are very high about what family members would like to have in terms of employment overseas,” says FLO Director Susan Frost.

She notes that six of the 25 staff in the Family Liaison Office work full time on family member employment issues. “They work very hard to try and help family members realize their professional goals,” Frost says. “It’s something we take seriously, and we work hard to try to make sure it’s successful.”

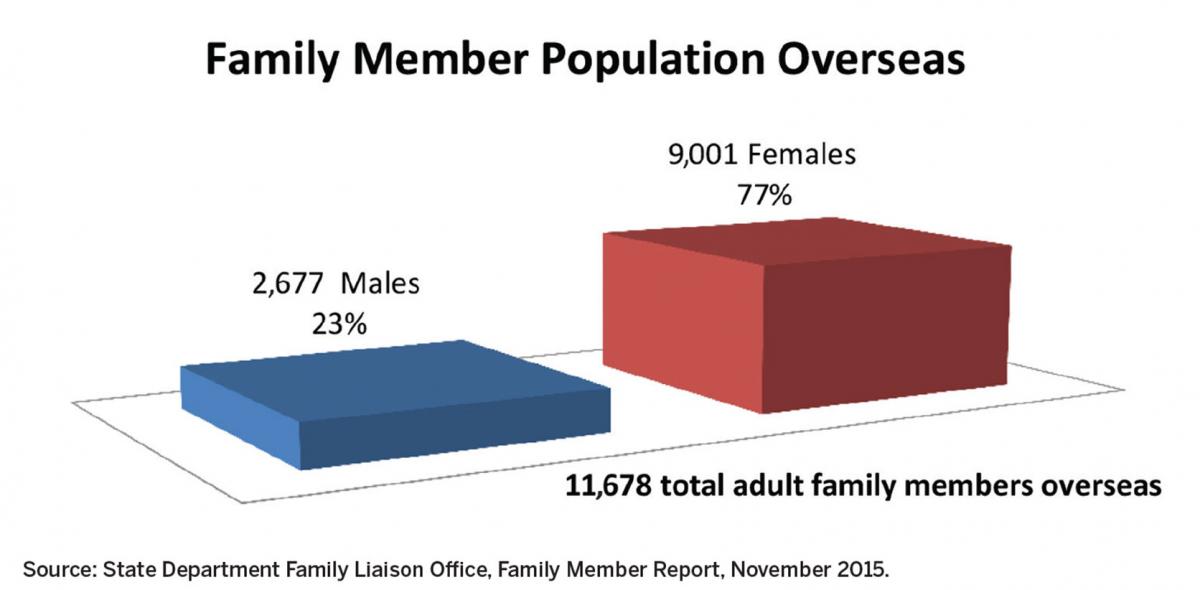

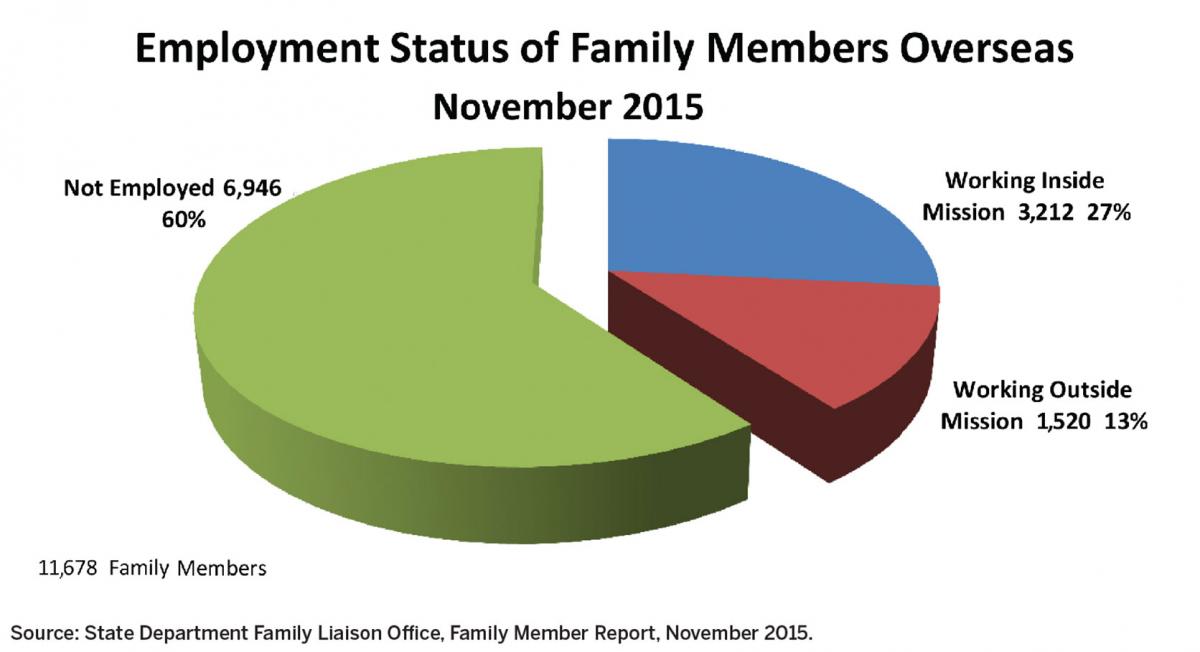

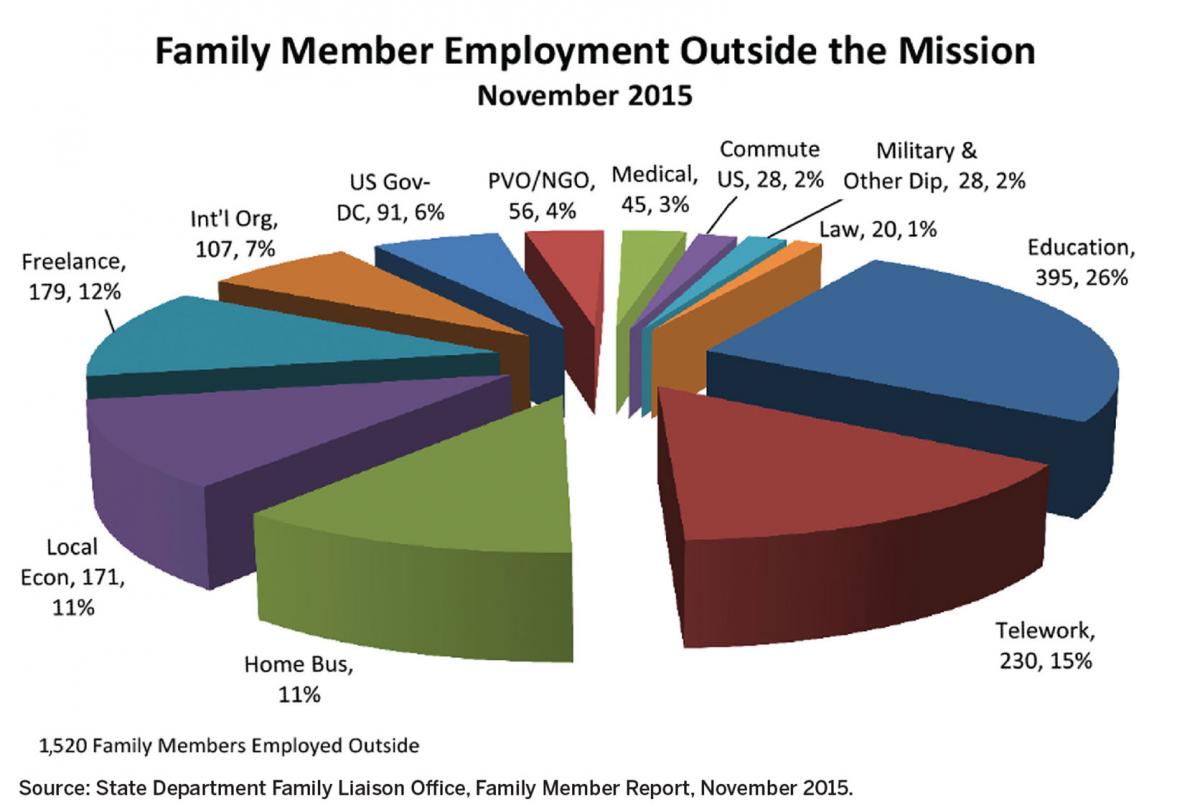

The most recent FLO employment report, issued in November 2015, shows that of the 11,678 adult FS family members overseas, 60 percent were not employed, 27 percent worked inside missions and 13 percent worked on the local economy. According to statistics on the broader workforce of the United States, the number of single-income couples among FS members is more than

10 percent higher than among their domestic counterparts. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, both husband and wife were employed in 47.7 percent of married couples in 2014.

What FLO doesn’t know is how many of that 60 percent of family members who are not currently employed are making the choice not to work—and how many would like to be working, but are either still looking for a job or have given up trying to find one.

As one spouse and blogger puts it, “Obtaining a job as an EFM is often a job by itself.” In her blog Diplomatic Impunity, “Kim E.” announced in a Feb 21, 2015, post that she was leaving the ranks of EFMs to become an FSO. “I do not have children to take care of, and I did not give up an extremely high-paying career—and still, at times, I felt more than daunted and jaded about the possibility of finding employment [as an EFM].”

The Associates of the American Foreign Service Worldwide took an in-depth look at the issue of family member employment a few years ago. Their compilation of articles highlights some of the unique challenges EFMs face, and offer suggestions for improvement, some of the same suggestions mentioned in the QDDR. Since then, an AAFSW committee on EFM employment has been in the process of writing an extensive position paper on the issue, which could become a real resource for innovative solutions once it’s presented.

Bob Castro, a member of the committee and the founder of Professional Partners and Spouses of the Foreign Service (PROPS), a LinkedIn network of professionally oriented FS family members, says collaboration among AAFSW, PROPS and other similar groups has, in effect, pushed the envelope on the issue of family member employment and prompted FLO and others within government to move more rapidly.

According to Castro—who won DACOR’s 2013 Eleanor Dodson Tragen Award for creating PROPS—employing family members is about more than just making spouses happy. It is also a way for the government to “leverage talent and resources that are already in place to be a force multiplier for mission objectives.”

EFM Employment Options at Post

What are the options for EFMs who haven’t given up on finding employment or joined the Foreign Service themselves? FLO lists enough employment programs and training opportunities to fill an 18-page brochure (“Family Member Employment and Training”). But with work spread out among more than 270 diplomatic missions overseas and more than 11,000 adult family members, many EFMs report that there aren’t enough opportunities to go around.

Working Outside the Mission. For spouses looking to work on the local economy, a number of factors come into play. First and foremost, does the United States have a bilateral or de facto work agreement with the country? Only if it does, and with permission from the post’s chief of mission, are family members permitted to work locally.

To help job-seekers, FLO has established the Global Employment Initiative, which is available to family members from all agencies at post, since FLO gets its program budget from International Cooperative Administrative Support Services (known as ICASS) in Washington. The GEI program evolved from a white paper FLO wrote 14 years ago and was granted initial seed funding by the Una Chapman Cox Foundation. Given the green light by then-Secretary of State Colin Powell, it has been a FLO-administered program for the past 10 years.

While many EFMs may wish otherwise, GEI is not a job placement service. Instead, regional global employment advisers (GEAs; currently there are 16 covering more than 200 posts) offer counseling and coaching, either in person or virtually, to help family members develop short-, mid- and long-term employment strategies.

Is the program a success? It depends on who you ask. Some EFMs report finding the coaching useful and the resumé-writing advice, in particular, invaluable. Others dismiss the service as something they could find elsewhere if they wanted it. “I think GEI advisers’ time would be better spent doing on-the-ground networking for EFMs who aren't yet at post,” says one EFM. “Getting a job takes a lot of face time that EFMs don't have during two- or three-year tours.”

FLO measures the success of the program by counting how many times family members reach out to GEAs for counseling sessions, and how many webinars or workshops are offered and the attendance of those events. Christopher Baumgarten, the employment program coordinator at FLO, notes that in 2014 GEAs held more than 4,300 one-on-one sessions with EFMs seeking employment. In 2015, they held more than 3,100 sessions.

Frost also points out that while there has been a 25-percent increase in the number of spouses and partners overseas in the decade, the percentage of family members who are employed inside or outside of a mission overseas has remained static.

“So that means employment and career-related programs have helped,” Frost says. “The department and other agencies have increased the number of positions and employment opportunities overseas in the same percentage as the number of family members have increased.”

Working Inside the Mission. Depending on the size and scope of the post, most missions have jobs open to family members. The jobs are often clerical or administrative though some, like the Community Liaison Office coordinator, can be professional in nature.

In addition to these, some posts (though not all) have positions that are available through different centrally managed programs that tap into the EFM labor pool and provide more professional work.

Centrally Managed Programs

The Expanded Professional Associates Program. This FLO-coordinated program opens jobs that are the equivalent of entry-level FSO positions to family members. The program offers a total of 200 EPAP positions plus 50 additional positions in the Bureau of Information Resource Management. Each year EPAP advertises these positions through a USAJobs vacancy announcement. Once selected for an EPAP position, EFMs are hired on a family member appointment (FMA), which means they receive danger pay but do not receive other allowances.

That means, for example, that at one Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs post that recently lost its danger-pay designation, the EPAP employee reported receiving $600 less per paycheck. The FSOs and specialists she worked with didn’t see the same reduction, because the cut in danger pay at post was offset by an increase in other allowances, which the EPAP participant was not eligible to receive.

Used for many EFM hires, the FMA mechanism was first introduced in 1998 and it offers some real benefits, including annual and sick leave, Thrift Savings Plan participation, health benefits and life insurance. And, most importantly, it gives EFMs the opportunity to earn non-competitive eligibility, which enables them to more easily fill federal jobs back in Washington.

But if an EFM is doing a job that is the equivalent of what an entry-level FSO would be doing, it can be hard for him or her to swallow this difference in allowances. And even though the FMA mechanism has real benefits, they’re not necessarily ones that soothe the EFM who feels the financial difference personally.

Spouses who participated in a discussion with the FSJ on EFM employment were unanimously skeptical that the EPAP program provided any real benefit to them. In addition to finding the hiring process cumbersome, these spouses agreed that they could often get higher pay and better jobs by working with the post’s human resources section directly. “I would argue that as an employee you are better off not in the EPAP program,” said one focus group participant.

Said another: “They want to take advantage of the qualified people at post, and they market the program as an entry-level Foreign Service officer. But they don’t want to pay you that way. And they expect you to take the same amount of leave and work full time.”

Professional Associates. Also known as the Hard-to-Fill program, this program is managed through State’s Office of Career Development and Assignments. Unlike EPAP, the positions in this program are actual mid-level FSO positions that have gone unfilled in the bid cycle and are then opened up to eligible EFMs, as well as to Civil Service employees. EFMs have preference in these jobs over Civil Service members, but they don’t have preference over FSOs—so could lose their assignment at any time if an FSO bids on it. There are also not very many of these positions open in any given year—about 35 a year, on average, for the past five years. Currently, only about 5 percent of those slots are filled by EFMs.

Consular Adjudicator Program. The Consular Affairs–Appointment Eligible Family Member Adjudicator Program is coordinated by the Bureau of Consular Affairs, and allows EFMs to fill entry-level consular positions at their spouse’s post of assignment. EFMs must go through a selection process to be qualified. Once certified, they remain eligible for positions for as long as they are EFMs. Since the program launched in June 2014, 89 EFMs have been fully certified. There is no fixed number of positions available each year, however; the needs of the Foreign Service dictate the number and location of openings.

EFM consular adjudicators are eligible to receive training as employees—meaning they will be paid during their training period and are not expected to take training on their own time. However, they are not eligible to receive per diem, so they either pay housing costs out of pocket or arrange training when their spouses are already in Washington, D.C.

Not Enough to Go Around

“The QDDR commits us to expanding these [centrally managed EFM employment] programs even further, and making them easier to access through a single portal,” Kathryn Schalow, the new special representative for QDDR, told the blogger known as Diplopundit, who wrote about the interview in an Aug. 31, 2015, post.

The commitment may be there, but no timetable has been established or goal set for completion of the task. And though on paper these programs seem to offer exactly what qualified EFMs are looking for—real professional jobs with real responsibility—they, in fact, have few actual openings. In addition, because of the hoops EFMs are required to jump through to qualify for these jobs, and because of the nature of EFM status and the mechanism of FMA hiring, these programs are not always seen in a positive light by the very people for whom they are designed.

One EFM describes the positions offered by EPAP and the consular adjudicator programs as just a “drop in the EFM bucket” and advised other spouses to “get off the EFM no-job, no-continuity merry-go-round and find something else.”

Security Clearance Delays

A major stumbling block to EFM employment within the mission is the length of time it takes for an employee to receive a security clearance.

Over the past year, the length of time needed, on average, to obtain a security clearance has increased across the federal government. According to Assistant Secretary of State for Diplomatic Security Gregory Starr, the delay can be attributed to the “increased workload, the shutdown of the Office of Personnel Management’s e-QIP (electronic questionnaire for investigations processing) system and a growing backlog of required checks that are provided to DS by other agencies.”

In the fourth quarter of Fiscal Year 2015, Starr reports, the government-wide average for top-secret clearances was 179 days. The State Department averaged 150 days. Starr says the State Department average is expected to improve further over the next few months—“bringing us closer to and hopefully within the ODNI [Office of the Director of National Intelligence] goal of 114 days.”

The number of single-income couples among FS members is more than 10 percent higher than among their domestic counterparts.

Though the State Department average is lower than the governmentwide figure, many EFMs still report long wait times for clearances. (One EFM at an NEA post reported waiting nine months for her clearance.) And if the EFM is foreign-born, the delay is often even longer. (The number of foreign-born spouses in the Foreign Service is not tracked, though the population feels fairly sizable. AAFSW reports having more than 300 members in its foreign-born spouse group.)

For an EFM at a two-year post, a nine-month wait for a clearance is interminable—especially when he or she will have to do it all over again at the next post.

Introducing the Foreign Service Family Reserve Corps

There may be a light at the end of the very long security clearance tunnel, however. On May 3, Under Secretary of State for Management Patrick Kennedy sent a cable to all diplomatic and consular posts (an ALDAC) announcing the Foreign Service Family Reserve Corps (16 State 49074).

“The FSFRC will create a workforce capable of rapid assignment to positions overseas, including sensitive positions,” the cable reads. In a nutshell, the FSFRC will be open to U.S. citizen spouses or domestic partners of employees and will allow members to retain their “eligibility for access to classified information”—i.e., their security clearances—as they move from post to post.

“Once fully implemented,” the cable reads, “the FSFRC will improve efficiency in the hiring and entry-on-duty process for appointment-eligible family members, centralize the administration of family member hiring and allow for certain efficiencies in security clearance processing.”

The department will begin phasing in the implementation over the next two years. The program will be managed out of the Bureau of Human Resources, Office of Shared Service, in Charleston, and FLO will handle communication. FLO’s website already includes an overview of the program, as well as an FAQ.

Working in Washington

For many family members, a move back to Washington, D.C., is just as difficult as an overseas assignment, if not more so. “Washington can be the hardest transition, because you don’t have the infrastructure there to help you that you have when you come to an embassy,” says FLO’s Frost.

Frost reports that FLO is always working on measures to help ease the transition on return to the United States. To help EFMs make the most of the non-competitive eligibility they may have earned overseas—a goal of the 2015 QDDR—FLO has collaborated with HR Shared Services to create a Register of those eligible for Non-Competitive Employment.

Announced by the State Department as we headed to press, this initiative will connect department hiring managers with potential job applicants, and ultimately facilitate their hiring across the federal government.

In addition, last September FLO hired a Washington-based GEA to offer the same kinds of coaching and career counseling it offers overseas.

“We’re trying to market family members,” Frost says, to hiring managers within the State Department. She reports that FLO has also begun to brief other federal agencies on the pool of potential employees among FS EFMs. Because of this push, Frost says, there has been a large increase in the number of positions advertised on the FLO Network, an email listserv of job openings FLO sends to EFM subscribers weekly. (Interested EFMs can sign up for the Network by making a request at FLOaskemployment@state.gov.)

Still More to Do

By creating the Foreign Service Family Reserve Corps, the Foreign Service is finally addressing one of the real stumbling blocks to EFM employment: timely security clearances. However, there is no indication that any of the current employment programs will be expanded, which is also a QDDR goal. Even the cable announcing the FSFRC made it clear that increasing the number of jobs available to EFMs was not a goal. “Fiscal constraints limit the department’s ability to create new positions overseas,” the cable reads. “Therefore the FSFRC, in and of itself, will not create additional employment opportunities.”

Still, the Foreign Service should get credit for officially recognizing that EFM employment is an issue it must address. “As evidenced by the QDDR,” says Under Secretary Kennedy, “the department has been working to improve the hiring process for our Foreign Service family members, who are,” he adds, “a valuable resource to fill available jobs at posts around the world, and we know that they want to work.”

Getting EFM employment right has never been more critical for the Foreign Service. Says AFSA’s Angie Bryan: “We have employees who are considering leaving the Foreign Service because they don’t see a long-term solution for a spouse who wants and expects to be able to work.”

Fulfilling the goals stated in the QDDR is essential. “It’s not like the Foreign Service of 20 or 40 or 60 years ago,” says Bryan. Foreign Service members “are not going to stick around if their spouses are unhappy.”

Read More...

- “New Civil Service and Eligible Family Member Opportunities as Limited non-Career Appointment Consular Adjudicators” (U.S. Department of State)

- “Introducing the Foreign Service Family Reserve Corps (FSFRC)” (U.S. Department of State)

- Focus on Family Member Employment (The Foreign Service Journal, April 2012)

- “FS Spousal Employment: Slow but Steady Progress” by Shawn Zeller (The Foreign Service Journal, April 2012)

- “Going Back to Work: A Step-by-Step Guide for FS Spouses” by Anna Sparks (The Foreign Service Journal, September 2015)