Travels with The Champ in Africa, 1980

The late Muhammad Ali was a diplomat extraordinaire, as this firsthand account of a mission to Africa attests.

BY LANNON WALKER

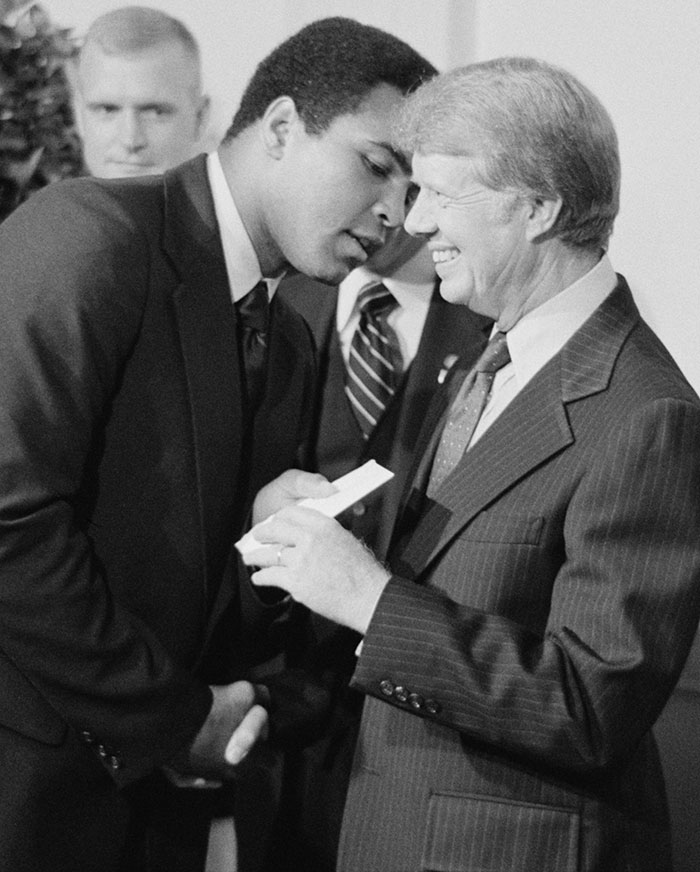

President Jimmy Carter greets Muhammad Ali at a White House dinner in 1977. Three years later Ali toured Africa at Carter’s request to enlist support for a boycott of the Summer Olympics in Moscow.

Marion S. Trikosko / Wikimedia Commons

The Angolans had put me alone in a guest house somewhere in the suburbs of Luanda awaiting the beginning of talks where the United States planned to trade off a warming of relations with the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola government in return for removal of Cuban forces from Angola. This was an opening we had been preparing for some time via the presidents of Gabon and Congo (Brazzaville), and I was primed and anxious to begin my secret mission. Neither Washington nor Luanda wanted publicity at this stage.

As night fell and boredom set in, there was a knock at the door. Expecting my Angolan contact, I was surprised to see the British ambassador, who formally represented U.S. interests, but who wasn’t supposed to know I was in town.

“Surprised to find you here, Lannon, and intrigued by the message I have been asked by Washington to relay to you,” said he.

As I read the telegram from the State Department, I couldn’t believe my eyes: I was being instructed to leave Angola immediately and to make my way to Tanzania. In Dar es Salaam, I was to meet Muhammad Ali, who would arrive from India in a White House plane, accompanied by members of the White House press corps and a State Department delegation. Thence, I was to accompany Ali, as his diplomatic adviser, to several countries in Africa to persuade their leaders to boycott the Moscow Summer Olympics because of the recent Soviet invasion of Afghanistan!

It took a while, but my British colleague finally persuaded me that it was, indeed, an official instruction from Washington.

An Imperialist Trap

After a nightmare trip involving three plane changes, I finally arrived at the Dar es Salaam airport, just minutes before Ali’s plane landed. Unfortunately, a huge crowd had already formed, and there was no way I could get through to meet Ali as he came down the stairs and was immediately swept away to the airport lounge.

When I finally fought my way into the lounge, Ali was in the midst of a tumultuous press conference, with the African press insisting that he had fallen into a trap laid by the imperialists, a plot that intended to use Africa’s hero to undercut its revolutionary goals. Ali looked upset and announced that if he was being misled, as the press suggested, he would take his plane and return to the United States forthwith. I imagined the headlines back home.

Finally getting to his side, I introduced myself and the purpose of our mission together. Ali said nothing, but we got in the car together and had a good exchange, with me outlining how I might be able to brief him before key meetings. Ali said that sounded good to him, and we pulled into the hotel parking lot—where the champ jumped out and began to shadow box with members of the crowd that had assembled to greet him.

The score so far: one loss in Tanzania, one win in Kenya and a technical KO by Ali in Nigeria.

It looked like good fun to me, but then a group of Black Panthers who were in exile in Tanzania swept Ali upstairs and into their room. I tried to keep up, but could only stand helpless at the door, imploring the champ to let me in. I could hear the Panthers telling him the same thing the African press had preached at the airport, and I wondered if my mission was dead aborning.

When Ali came out, he announced that he was hungry, so we went to his room and I witnessed for the first time the gargantuan amount of food the champ could put down. The next day, we learned that President Julius Nyerere had canceled his meeting with Ali, citing the same line as the press and the Panthers had used. Again, I imagined the headlines back home.

The next day, as we flew to Nairobi, Kenya, I told the champ that we would have an easier time with President Daniel Arap Moi, a strong ally. Ali asked me to describe Moi and to brief him on the politics of Kenya and the approach to take.

I thought for about three seconds and told him that Moi was a schoolteacher from a minority tribe who had served as vice president with the founder of Kenya, a strong and authoritarian ruler who brooked no interference with his wishes. I mentioned that Moi would be accompanied by his vice president, who was very ambitious and couldn’t wait to sit in the presidential chair.

And that was it. I wanted to see how Ali would introduce himself and his goal of boycotting the Moscow Olympics, and figured that we could pull it off given the receptivity of our Kenyan hosts.

Off and Running

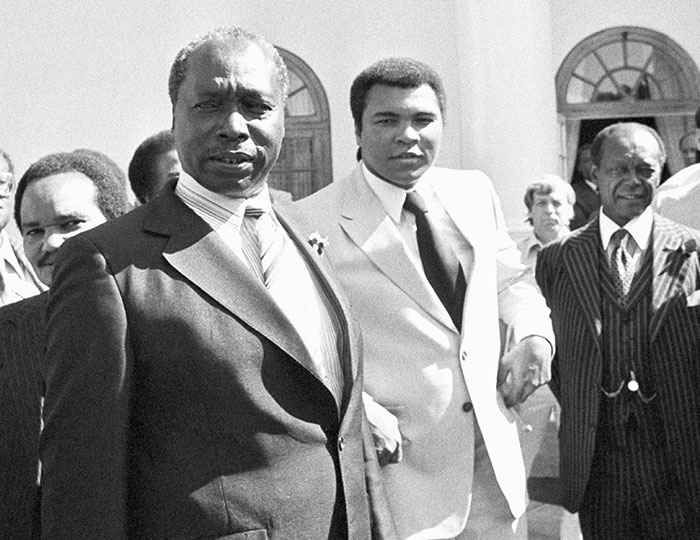

Muhammad Ali meets with Kenyan President Daniel Arap Moi at the State House in Nairobi, Kenya, on Feb. 5, 1980, during the Olympic boycott mission.

Associated Press

Moi received us at the presidential palace with all the necessary protocol and began to welcome Ali with a stiff and traditional set of remarks. Ali interrupted him and asked: “Did you always want to be president? Did you have a plan, and did you follow it?”

At first startled, Moi then said: “No, I always wanted to be a teacher, and I just did my job and events took over.”

Ali rejoined: “That’s right. You just did your job and served your country. You had no driving ambition to be president, unlike some people we know”—and he looked straight at the vice president!

Now I’ve done it, I thought. We’re going to have a major diplomatic incident. But no—Moi instantly dropped his stoic demeanor, warmed up to Ali and proceeded to literally block the vice president out of the conversation. Things went swimmingly, and the press release was just what Washington wanted. We were off and running.

Or so I thought, until I looked at the next programmed stop on the itinerary: Nigeria. I sent an urgent message to the State Department reminding them that the Nigerians were not at all on the same wavelength as we were on almost every issue, and certainly not on the question of the Moscow Olympics. I strongly recommended that we cancel the stop in Lagos and reroute the plane to Kinshasa, where President Mobutu Sese Seko would guarantee us a huge crowd and solid support for our position.

Washington responded that Mobutu was not the ally they wanted to put front and center on this trip—and, besides, we had been told that the president of Nigeria and a host of senior ministers had agreed to meet with us.

As the plane taxied at Murtala Muhammed International Airport, one of the cabin crew came to me to say that I had a call on the radio in the cockpit. When I picked up the handset and identified myself, an American voice said: “Just wanted to warn you that all of your appointments have been canceled.” I asked who was on the line, but it had gone dead.

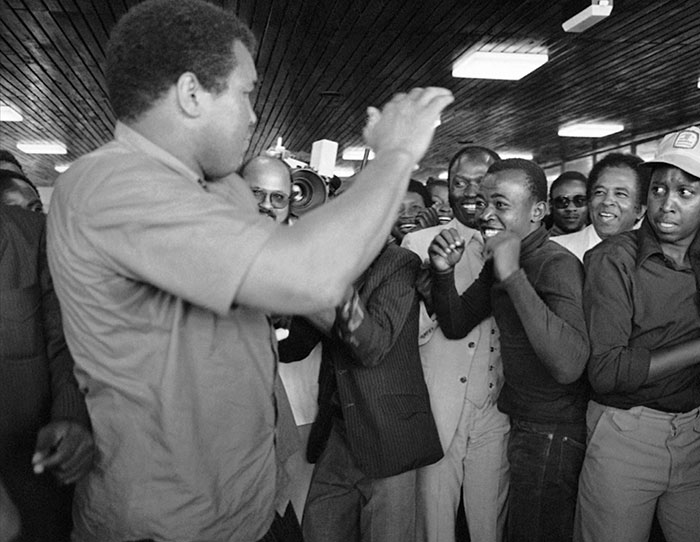

Ali spars with a Kenyan fan after deplaning at Nairobi’s International Airport on Feb. 4, 1980.

Associated Press

Arriving at the plane’s exit door, the champ asked me who we had for the first appointment. I told him that there was a slight change in plans, and that we would go first to the U.S. ambassador’s office.

As we settled into our chairs, I asked the ambassador to explain to Ali where we stood on the appointments. When the champ heard that they had all canceled, he stood up in a fury and said he was going to take his plane and return to the United States.

“Champ,” I said, “when you’re in the ring and someone has you on the ropes, do you leave the ring?”

“I get your drift,” Ali said, and turned to the ambassador. “Where’s downtown?” he asked.

Neither the ambassador nor I had the slightest clue what he was driving at. But when the ambassador mentioned Tinubu Square, Ali took me by the arm, “Let’s go there now.”

The long line of minibuses that had brought us from the airport was downstairs waiting, press corps and State Department delegation included. As we pulled into Tinubu Square, Ali jumped out and began to shadow box with passers-by, of which there were hundreds.

Soon he was recognized, and the growing crowd began to chant: “Ali! Ali!” When he had whipped them into a frenzy, he turned to me: “Where was that first appointment?”

I replied that I had gotten his drift, and off we went with a large, chanting crowd in tow to the foreign ministry and our first appointment. We saw other ministers, but not the Nigerian president.

The score so far: one loss in Tanzania, one win in Kenya and a technical KO by Ali in Nigeria.

The next stop was Monrovia, Liberia, a friendly nation once founded by freed American slaves and sure to back us in our pleas to boycott the Moscow Olympics. Having learned my lesson in Kenya about Ali’s ability to turn meetings to his advantage, I simply told him that President William Tolbert Jr. had been a preacher. And, indeed, the president’s office was set up like a mini-church, with rows of pews facing the chief of state’s desk.

Tolbert was very formal, welcoming Ali and me with all the old-style protocol of which the Liberian state was so enamored. As he spoke, Ali leaned forward from his pew and began to chant: “Speak to me! That’s right, speak to me! I hear you preaching. Oh, my Lord…”

His sense of timing and his ability to get inside his interlocutor’s head and heart were a beauty to behold.

I thought, now you’ve done it—managed to get the champ to insult a strong ally and probably lose sure support. But no—Tolbert began to rap back, and before my eyes the two were transformed into brothers. We were on a roll.

As we pulled into the airport at Dakar, our last stop, there was the usual press conference that we had encountered at every stop. But this time, everyone was tired; they had heard the questions and Ali’s answers over and over. The TV cameras were turned off, and folks were about to take a nap—when a reporter stood up and, with a heavy Russian accent, launched into the same line about an imperialist ploy that we had heard in Tanzania.

The press corps began to wake up when Ali looked at the reporter and asked, “Are you a Russian?”

Yes, was the answer.

“Are you a communist?” Ali continued.

After some hesitation, a reluctant yes came out.

“Well,” said Ali, really wound up now, as if this were the last championship round. “I’ve been to your country. You don’t believe in God. Well, I’ll tell you something, we’re in Africa here, and we believe in God!”

The Russian sat down, abashed, as the press corps and onlookers cheered. The champ raised his arms in victory.

“Could I Be a Diplomat?”

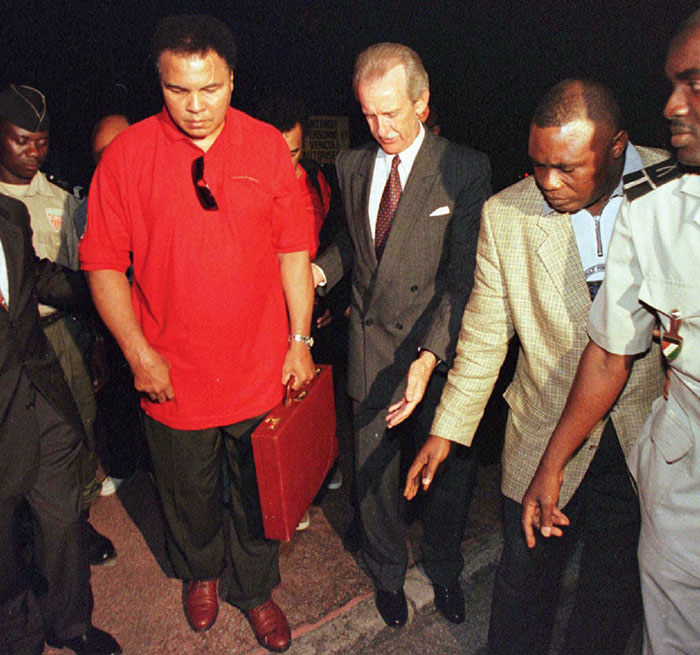

Muhammad Ali arrives in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, on Aug. 18, 1997, on a mission to deliver food to 400 orphans living in a refugee camp at San Pedro along the Liberian border, where tens of thousands of refugees who fled Liberia’s civil war were living. A nun caring for the children wrote to Ali asking for his help. Ali is assisted by U.S. Ambassador Lannon Walker, Côte d’Ivoire government officials and police officers.

Associated Press

Washington considered Senegal to be a sure thing, but I told Ali that President Leopold Senghor, an honest man, had refused to go along with an Olympic boycott against South Africa on the grounds that politics and sports should not be confused. He would not change his stance, I said, even for Muhammad Ali—but as a renowned poet, he would welcome a brother bard. I told the champ to enjoy the interchange.

And that’s what happened. Pres. Senghor invited us all to his personal seaside residence, where he and Ali hit it off as they recited their poetry. It was a perfect end to an extraordinary mission.

As Ali’s plane took off for Washington with the press corps and State Department delegation, I remained on the tarmac. I had to get back to that aborted meeting in Luanda, I thought. Ali waved at me with a twinkle in his eye, as I am sure he recalled the several long conversations we had had along the way centered on his question: “Do you think I could do more of these missions? Could I be a diplomat?”

I had told him then, and I meant it, that he was “a diplomat extraordinaire.” His sense of timing and his ability to get inside his interlocutor’s head and heart were a beauty to behold. Ali combined a sense of strategy, learned from the ring, with the unparalleled ability to muster popular support, above and beyond any government’s policy. This dynamite combination gave him power and entrée no ordinary diplomat can muster. I wanted him to come with me to Angola.

There was more, of course, to Ali’s mission than his meetings with chiefs of state and the press. Our ambassadors and their missions went all out to arrange programs where Ali could meet the people, especially local boxers, and generally show his profound generosity. Our State Department delegation handled the public diplomacy and saw to it that his strengths were displayed optimally. It was a very good show, and the Russians got the message. Their Olympics had been overshadowed by The Champ.

Years later, Muhammad Ali came to Côte d'Ivoire, where I was ambassador, to support an American Catholic nun who ran an orphanage in the eastern city of San Pedro. In a planning meeting, my Ivorian colleagues assured me that all measures had been taken to ensure security and a smooth visit.

I smiled and warned them that all their plans would go awry when Ali came off the plane. Everyone, including the protocol planners, would leave their scripts in the dust as they scrambled to reach Ali and to be able to say that they had touched the champ. And that’s the way it was.

Ali was diminished in body; but his mind, good humor and strategic sense were strong. He was still on a mission to use his own power and prestige to help others. We reminisced about his mission to Africa, and I saw the fire return to his eyes. He was ready to go again.

Read More...

- “In pictures: Muhammad Ali's love affair with Africa” (BBC, June 2016)

- Muhammad Ali Center