Working a Presidential Transition: First-Person Accounts

Stories from past presidential transitions, as told by Foreign Service officers who worked through them.

COMPILED BY DANIEL EVENSEN

Throughout the storied history of the U.S. Foreign Service, career diplomats have dealt with periods of political transition with professionalism and flexibility.

The oral history collection managed by the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training (ADST) contains numerous personal accounts of successful transitions told by diplomats who used the transition of power from one administration to another as an opportunity to recommend new initiatives and policy changes that would increase efficiency and fix problems.

From the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy in 1961 to the inauguration of President George W. Bush in 2001, the stories that follow, taken from ADST’s archives, demonstrate how skilled Foreign Service officers have used past presidential transitions to advance the work of American diplomacy.

The following excerpts from ADST’s oral histories have been lightly edited for clarity. For more fascinating firsthand accounts from practitioners in the field, go to https://adst.org/oral-history/.

1961

From Eisenhower to Kennedy: Ambassador Nicholas Veliotes

“Don’t Take Anything for Granted”

President Dwight D. Eisenhower meets with President-elect John F. Kennedy in the Oval Office, Dec. 6, 1960.

Abbie Rowe / White House

There were two things about the transition that struck me very much.

Kennedy’s personal curiosity and his desire to know became clear very early. I remember … Kennedy sent a query back on why we had recommended he not respond to the congratulatory letter of the East German president. And we were shocked. I was handling Europe at the time in the Secretariat. I mean, how could this guy not know that we don’t recognize them, and the consequence of recognizing them, our relationship with West Germany and all of this?

We had a brilliant director of German affairs at the time, Martin Hillenbrand. … We decided, maybe what the president really needs is just a two-page background on why. … Kennedy read it and said fine, I understand that. That got everyone knowing that you don’t take anything for granted.

The other thing was the nature of the changes that Kennedy brought into the State Department. There was nothing hostile about them. Whereas the previous executive secretaries had been [mid-level FSOs, Secretary of State Dean] Rusk’s executive secretary was [Ambassador] Luke Battle. And clearly the signal was that he, Dean Rusk, was going to put his stamp on the place, and he was going to use the Secretariat as his mechanism. That changed the nature of the job, and you had a much more activist Seventh Floor. …

There was no hostility involved. … Certainly the career officers were not hurt. There even was a major effort made to demonstrate nonpartisanship. Bill Macomber, whom everyone confuses with a career officer, was a political appointee of John Foster Dulles, and when the administration ended, Macomber, I believe, was assistant secretary for congressional affairs. The decision was made, deliberately, to offer Macomber (a clearly identified Republican appointee who had worked very closely with the Eisenhower administration and the previous Secretaries of State) an embassy.

That carried a message that was very positive. Totally different from what [had] happened to [Special Assistant to the Secretary] Luke Battle when the Republicans came in in 1952. He was literally hounded out of the Foreign Service because of his close relationship with Dean Acheson and others. So [in 1961] you had just the opposite of hostility, you had a feeling that these people appreciated us and that they were not going to play a game of witch-hunting against the career officers.

1969

From Johnson to Nixon: Donald F. McHenry

“Still a Period of Bipartisanship”

In November, right after Nixon was elected, I was sitting in my little office and the phone rang, and it was William Rogers, whom [President Lyndon] Johnson had appointed in 1967 or so as the U.S. representative on the Special Commission on Southwest Africa, and I had been sent off to be his adviser. In any event, in November of 1968, the phone rang, and it was Rogers, saying that Nixon was going to appoint him Secretary of State. Rogers didn’t know that many people in the State Department, but he knew me and wanted me to work with him and Dick Pedersen, who later became the ambassador to Hungary, on the transition from Johnson to Nixon. And so I worked on the transition team. I was detailed to the Nixon transition team, … November, December, and January, 1968-1969. …

It was still a period of … bipartisanship in foreign policy. Some of the people were brought back in, like [U. Alexis] Johnson—a career officer who was simply brought back in a higher position in the new administration. Dick Pedersen, who had been up at the United Nations, was brought in. Elliot Richardson, who was an eastern Republican stylistic figure, came down as under secretary of State, the number-two position. I don’t think that there was as much ideology in that transition as we saw, for example, from Carter to Reagan. I say that despite the fact that Nixon made any number of speeches in which he talked about the State Department and that he knew who the good guys were and the bad ones, and that he was going to clean up the place, and so forth. There wasn’t that much of that at the time. And, of course, Rogers was really a gentle and decent person, and Richardson was.

What we saw, however, early on, was not the sharks taking over so much as the complete takeover of foreign policy by the White House, specifically by [Henry] Kissinger and the National Security Council staff. And we know that’s what Nixon wanted to do. …

In the transition period, I saw it occurring. I saw those drafts of Nixon’s first [National Security Council]. ... And it was very clear to me that they were setting up a structure in which the Secretary of State was going to be frozen out. In fact, I told Secretary Rogers, and he expressed the view that it didn’t matter what the bureaucratic structure was, he was going to be Secretary of State, and when he wanted to get to the president, he would.

1969

From Johnson to Nixon: Benjamin H. Read

“Full Disclosure All Around”

I was appointed … for the transition, so I saw quite a bit of [cooperation with the incoming Nixon administration]. I think it was done quite well. … It was one of the most civil transitions between parties that had occurred, unlike 1980.

There was very full disclosure, offerings of briefings. [Incoming Secretary of State] Bill Rogers and [outgoing Secretary] Dean Rusk met repeatedly. Unlike Secretary [James] Baker and Secretary [George] Shultz. We gave them an office right on the seventh floor, yards away from the Secretary’s office where Bill Leonhart and the under secretary of the Eisenhower period, the famous diplomat Bob Murphy, were putting together the personnel for State. Henry Kissinger had run a Vietnam peace initiative for LBJ, and I knew Henry quite well. I went up to the Hotel Pierre to see him a few times, and I don’t think it could have been handled much more gracefully than it was, although I’m sure there were glitches at different levels.

I didn’t see Nixon during this period. I saw some of his staff who became notorious during that time. The State Department’s whole transition team was very effective and had entrée anywhere they wanted. They got just as full briefings as they desired. There had been briefings during the campaign of Nixon or his designees. The transition was pretty well done, I think.

1977

From Ford to Carter: Morris Draper

“Not a Bureaucratic Exercise”

There was some change. The transition of administrations was managed by Phil Habib, who stayed on as under secretary for political affairs. That made for a very smooth transition. It was also exciting because, as is customary, we prepared transition papers on every country and every issue. On the Middle East, around Christmas time—that is after the election, but before inauguration—we had reason to believe that the Secretary of State–designate and probably Carter himself had looked over our papers and were considering a major initiative. If historians ever examine these transition papers, they will find that the quality was very high.

Moreover, we were encouraged by Habib to be imaginative and not to prepare the papers just as a bureaucratic exercise. I remember the period quite vividly because I submitted a paper early on the Lebanon problem, which Habib circulated to the bureaus as a model of what he wanted in terms of the thrusts and options. So there was a lot of excitement in the Near East Bureau at the time, which may not have been shared by others.

Of course, Carter was also introducing other concepts into our foreign policy, like the emphasis on human rights.

1993

From George H.W. Bush to Clinton: Hans Binnendijk

“An Opportune Time to Make Change”

I mentioned that in late 1992 and early 1993, I worked on the transition team. I had some work for the Clinton campaign team, mostly for Madeleine Albright, who was at the time a professor at Georgetown and director of a small think tank that was politically active. During the campaign, one of her functions was to organize a speakers program. I was one of her “stable” and, for example, debated on behalf of Clinton at a forum organized by the Chicago Council for Foreign Relations. When Brian Atwood, whom I had known for several years, was designated to head the transition team for the State Department, he asked me to join him to work on organizational issues, which I did. So I worked for a couple of months on that, together with Dan Spiegel—another old friend from my Senate Foreign Relations Committee staff days.

President Gerald Ford and First Lady Betty Ford (at center) with President-elect Jimmy Carter and Rosalynn Carter following the Carters’ tour of the White House, Nov. 22, 1976.

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum

I found working on the transition team very stimulating because we had the sense that … the time was opportune to effect some change. It is hard to change organizations after an administration has been established—short of cataclysms such as the recent forced amalgamations of foreign affairs agencies. But in transition, we could begin with a relatively fresh page and suggest some changes. I found it stimulating to think about the department’s organization and consider various ways to increase its efficiency. Spiegel and I wrote a series of reports, which were incorporated into briefing books for Warren Christopher, the new Secretary. We briefed Christopher several times, and a number of decisions were made based on our recommendations.

We reinvigorated the under secretarial system by assigning to each under secretary responsibility for certain bureaus. … We suggested that in response to practices that had grown up under Baker—he would bring in five or six people every morning, without regard to official roles that these people played, and make policy right then and there in this informal group. Our view was that such practice would probably continue under any Secretary; any Secretary would convene a small group of personal advisers, but we strongly hoped that such a group would include several under secretaries, who were the operating linchpins in the department.

We tried to take a natural behavioral pattern—a small group of advisers—and institutionalize it by including in it a number of officials responsible for the day-to-day activities of the department. We recommended the creation of an additional under secretary—for global affairs—and in general tried to strengthen the role of the under secretaries by having them frequently in touch with the Secretary, which would allow them to serve as conduits for his or her wishes to the department’s bureaucracy. That didn’t work out quite as well as we had hoped, but it was probably better than the Baker system. The problem was that some of the under secretaries did not connect well enough with the bureaus and the assistant secretaries often felt cut out.

We recommended some other changes. The one which probably had the greatest impact on the bureaucracy was to radically cut the number of deputy assistant secretary (DAS) positions—about 40 percent. The idea was to try to reduce a top-heavy bureaucratic structure and increase the responsibilities of office directors. We found that a number of deputy assistant secretaries were essentially glorified office directors. By reducing the number of DAS positions, we hoped to strengthen the role of the office directors. I think that worked; the number of DASes were cut substantially, although I have recently noticed that the number is creeping up again.

I found my work on the transition team to be interesting and fruitful, with an immediate and visible payoff for our recommendations.

2001

From Clinton to George W. Bush: Marc Grossman

“What Is Your Plan?”

President Bill Clinton and President-elect George W. Bush shake hands during their meeting in the Oval Office, Dec. 19, 2000.

White House Photo Office

In the fall of 2000, [Langhorne] Tony Motley—who had been ambassador to Brazil, an assistant secretary for Secretary [George] Shultz, and was a mentor of mine (he was always asking me if I was thinking about things in the right way)—called me up and said, “Marc, are you thinking about the next Secretary of State?”

… He said: “You need to think about numbers. The next Secretary of State is going to sit down with you and he or she is going to say, ‘Where are all of my senior officers?’ You need to know, ‘Who are my senior officers? Where are all my junior officers?’” In other words, that person is going to want all this data sliced and diced in dozens of different ways.

Also, he asked me: “What is your plan? What do you want? What do you need?”

I got the “skunk works” folks in, and this effort was led by Bill Eaton. I said: “We have six weeks to figure this out, so go away and think about all the questions you would ask if you were the new Secretary of State and then let us get them answered, statistically and with lists; let us just really do this up. And then let us think up something to ask the new Secretary for.”

So Bill and Maureen [E.] Quinn came back after a while, and they did a fantastic job on the numbers. I had been reading that military units have a 15 percent personnel float for training and transit, so that every military unit is only really staffed up if there is 15 percent on top of whatever they have in the unit. I said, “Why not us, why can’t we do that?”

I asked everybody in personnel, and I said: “Think about this. What would 15 percent be? Could we recruit that many new people if we had the money? Over what period of time? Does FSI have room to train them?” We worked on this, and we came up with the numbers, and then President Bush 43 was elected, and Colin Powell was named Secretary of State. And I said: “Lucky us, here is the person who will understand this.”

We put together a really good presentation about why we needed a 15 percent float, and 15 percent for us, total State Department, was just under 1,200 people. We made a budget, imagined a timeline. And so, thanks to Tony Motley’s call and some very creative work by the bureau, we were set.

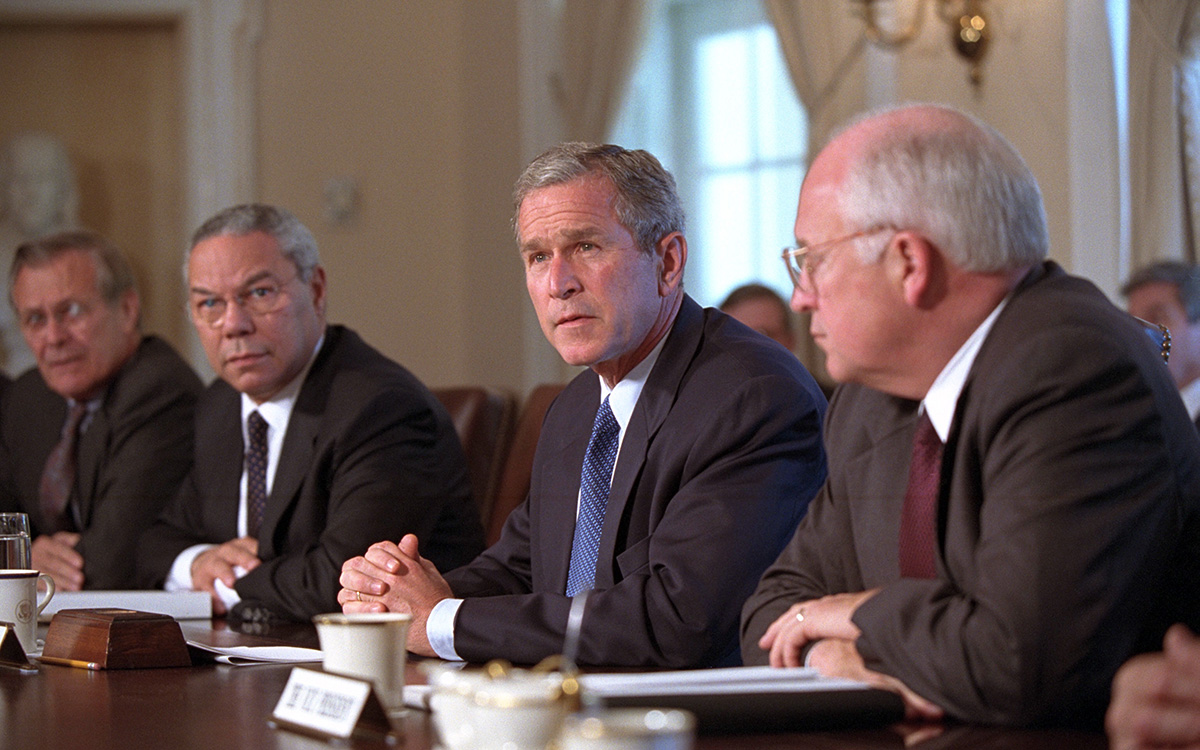

President George W. Bush and Secretary of State Colin Powell at a National Security Council meeting on Sept. 12, 2001.

White House Photo Office

Just before Christmas of 2000, I was in the car with a bunch of kids in the back seat, and we were going through the Christmas light show at Bull Run Park. So all these kids are in the back seat and we are driving through the park, and the phone rings. It’s the Ops Center; it’s Colin Powell. I tell the kids to be quiet.

He gets on the line, and he says: “I am coming to State tomorrow. Give me a few hours to get settled in my office, and then I will come call on you, because I would like the first person I call on to be the director of personnel. Are you ready?”

I said: “Yes sir, I am ready. But I have something to say.”

“What?” he asked.

I said: “I will come call on you. … Because if you come to call on me there will be a riot on the Sixth Floor, and it would be disrespectful to Secretary Albright.” And he said, “Okay, come see me.”

The next afternoon I went down to see then Secretary-Designate Powell in the transition suite. I introduced myself and he started to ask me questions. He asked me all the questions Tony Motley said he was going to ask me, and, thanks to Tony and the HR team, I had the answers. At the end, he said: “So, what could I do for you? What would really show the people here something really great, something fantastic?”

… I pulled out my slides on the float, which I called the Diplomatic Readiness Initiative. I pitched him, and he said, “First of all, I have to tell you I hate the name ‘diplomatic readiness.’” I said, “I do not care what you call it, actually, if you give me 1,200 people.” And he said, “We will have to think about the name.”

I said: “You are going to testify to the need for readiness. Who better to testify about the need for readiness than the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs?”

He said: “I hate the name, but the substance is great. I commit to you, right this afternoon, that we will get these 1,200 people over three years.”

I said: “Really?”

He said: “You have my word.”

And that is what started the DRI (because in the end he could not think of a better name, and I could not think of a better name), which has been pursued so successfully by my successors, Bob Pearson and Ruth Davis, with strong support from Under Secretary for Management Grant Green. We hired just under 1,200 people in three years. Of course, as we sit here today, we still do not have a 15 percent float for training and transit because most of those people were taken up in Afghanistan and Iraq. But we had the people.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “Integrity and Openness: Requirements for an Effective Foreign Service” by Kenneth M. Quinn, The Foreign Service Journal, September 2014

- “Still Telling Their Stories: ADST’s Oral History Program” by Kenneth L. Brown and Veda Engel, The Foreign Service Journal, July-August 2003

- “A Century of Service: Firsthand Accounts from U.S. Diplomats” compiled by Tom Selinger, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2024