Does America Spend Too Much on Diplomacy?

President's Views

BY BARBARA STEPHENSON

I ended my last column, a holiday message written with special thoughts of our colleagues deployed far from home, with a wish for a strategy to guide our work on behalf of the American people. That has arrived by way of the new National Security Strategy. While the NSS may not define clearly America’s role in the world, it nevertheless makes a powerful case for the indispensable role of American diplomacy and development.

This column will explore the National Security Strategy and the related question of whether America spends too much on diplomacy. Even though budgets are complicated beasts, I ask that you stay with me so that you, stewards of this great institution, are able to speak authoritatively about this vitally important issue.

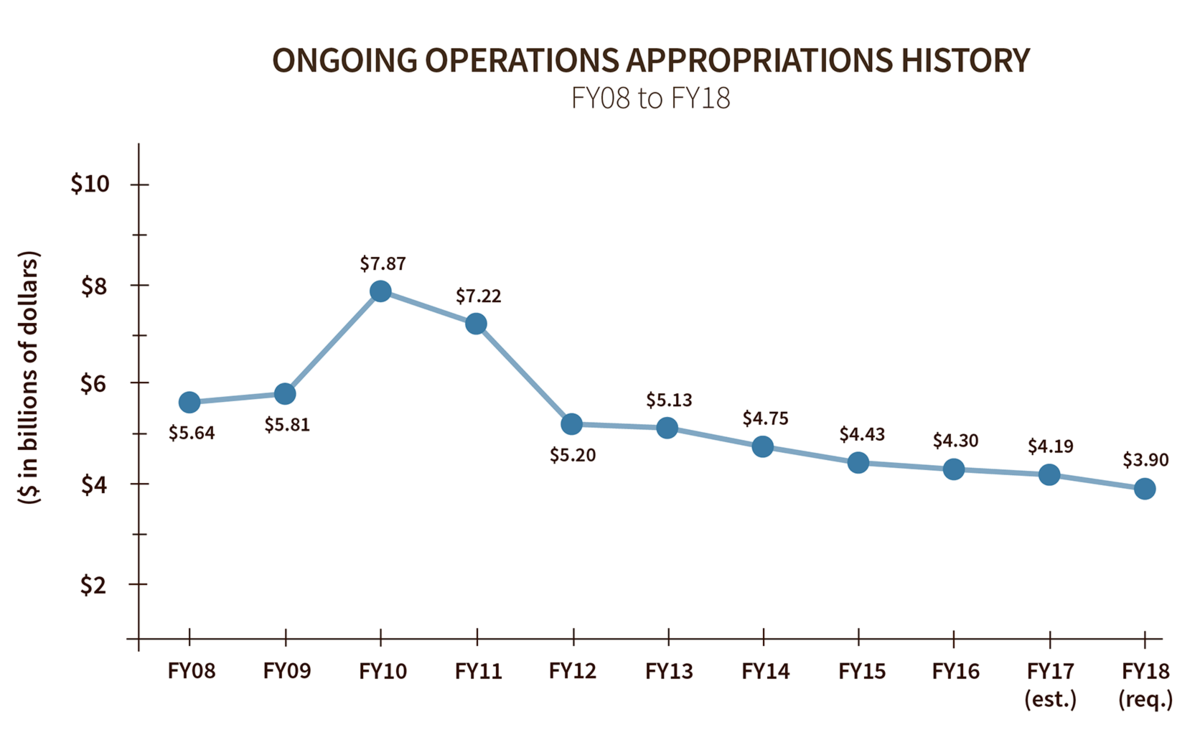

Here’s the bottom line: The annual Congressional Budget Justifications for the State Department show clearly that spending on core diplomatic capability actually declined over the last decade (see chart and sidebar).

If we compare 2008, the last full year of the Bush 43 administration, to 2016, the last year for which actual spending figures are available, the decline in spending on core diplomatic capability is dramatic—from one dollar in 2008 to just 76 cents in 2016, in nominal, non-inflation adjusted terms.

The 2018 budget proposal would take spending on core diplomatic capability down further, to 69 cents of the 2008 dollar.

Even when we account for shifts in how the CBJ reports costs, spending on core diplomatic capability in 2016 was still below 2008 spending in nominal terms. If we then factor in inflation, 2016 spending on core diplomatic capability was only about 77 percent of 2008 spending.

Source: p.22, FY2018 Congressional Budget Justification, Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs

Core Diplomatic Functions Defined

State Department Congressional Budget Justifications (CBJs) contain a consistent budget category named Ongoing Operations. This budget category represents what the department describes as its “core” diplomatic functions, defined as “in-depth knowledge and understanding of political and economic events in many nations [as a] basic requirement of diplomacy,” through “reporting, analysis and personal contact work,” as well as through public diplomacy activities “intended to understand, inform and influence foreign publics and broaden dialogue between American citizens institutions and [our] counterparts abroad.” (FY2002 CBJ Submission for the Department of State, p. 16).

So much for the narrative of runaway growth in spending on diplomacy. When we look at the numbers, the picture that emerges is one of a capability that has been starved of resources for years.

Yes, the overall budget has increased, with the growth in security costs a major factor. Spending on Worldwide Security Protection was 17 percent of the total “Diplomatic and Consular Programs” budget in 2008. As the 2018 CBJ shows, by 2016 WSP had grown to 41 percent of the total D&CP budget, while the share for core diplomacy was squeezed to 59 percent.

The proposed budget for 2018 continues this trend, with WSP growing to 45 percent of total D&CP spending while core diplomacy declines further, to 55 percent.

Given that State provides the operating platform for all executive-branch personnel posted to embassies and consulates, this growth in Diplomatic Security is not surprising. But we should not mistake increased spending to support the executive-branch platform with spending on core diplomatic capability.

The fact is that spending on core diplomatic capability has declined. I’ve seen this reflected in what I have heard in structured conversations and in leadership classes. Political, economic and public diplomacy sections in embassies are generally so thinly staffed—many have not been restored after the “Iraq tax” a decade ago—that not only does mentoring suffer, but so does the high-impact diplomacy that underpins our global leadership role.

By the time required reports are written, required demarches delivered and visits handled, depleted sections have little capacity for the crucial diplomatic work of building up the bank account of relationships and trust.

As a career diplomat, I have long lamented this as a penny-wise, pound-foolish approach to maintaining America’s global leadership. How reassuring, then, that the new National Security Strategy makes such a clear case for diplomacy.

The president’s cover letter states: “The United States faces an extraordinarily dangerous world, filled with a wide range of threats that have intensified in recent years.” The NSS is unequivocal on the “indispensable” role of diplomacy:

“America’s diplomats are our forward-deployed political capability, advancing and defending America’s interests abroad.”

“Our diplomats must be able to build and sustain relationships. … Relationships, developed over time, create trust and shared understanding that the United States calls upon when confronting security threats, responding to crises, and encouraging others to share the burden for tackling the world’s challenges.”

“We must upgrade our diplomatic capabilities to compete in the current environment.”

The NSS makes clear that America faces many threats and needs upgraded diplomatic capabilities. Yet the proposed budget would cut diplomatic capacity even further, compounding the loss sustained over recent years of scarce resources.

The last time America reduced its diplomatic capacity sharply (though not as sharply as today) was in the mid-1990s. The Berlin Wall had come down, America had “won” the Cold War, and the logic was that we could afford to scale back on diplomacy. There was a national conversation, and Congress cut funding for State.

Spending on core diplomatic capability actually declined over the last decade.

History has shown how short-sighted those 1990s cuts were. They ultimately produced the dire staffing shortages we faced a decade ago when we needed a deep bench of seasoned Foreign Service leaders to staff the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

Where is the national conversation now? That is precisely what Senator Lindsey Graham, chairman of the State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee, is calling for in his 'Message from the Hill' in this issue of the Journal.

I remind you that the report from that subcommittee (approved by a 31-0 vote in the full Appropriations Committee) rejected the proposed cuts to State funding as a “doctrine of retreat” and instructed that appropriated funds “shall” be used to maintain State staffing at Sept. 30, 2016, levels and to resume entry-level hiring.

Yet even in the face of this clear expression of congressional intent, this explicit rejection of deep cuts to State’s budget, the depletion of the Foreign Service continues.

The Foreign Service officer corps at State was down to 7,940 at the end of December, from 8,176 in March 2017, a drop of 236.

The loss is heavily concentrated at the top. With Career Ambassador Tom Shannon’s departure, State’s four-star ranks will be down to just one, from six at the end of 2016.

The number of Career Ministers (three-stars) has fallen from 33 in December 2016 to 18 today. And Minister Counselors (two-stars) are down from 470 to 373 during the same period.

The answer to the question of whether America spends too much on diplomacy is No. And so the question “Why make such cuts?” remains as pressing today as it was in November when I first asked.

We urgently need a national conversation about the dismantling underway of a vital instrument of national security. The American people deserve one.