Ebenezer Bassett: The Legacy of America’s First African-American Diplomat

This pioneering diplomat foreshadowed the critical role of human rights in U.S. foreign policy.

BY CHRISTOPHER TEAL

Chris Teal at the Bassett family gravesite in New Haven, Connecticut, during the film shoot.

Courtesy of Chris Teal

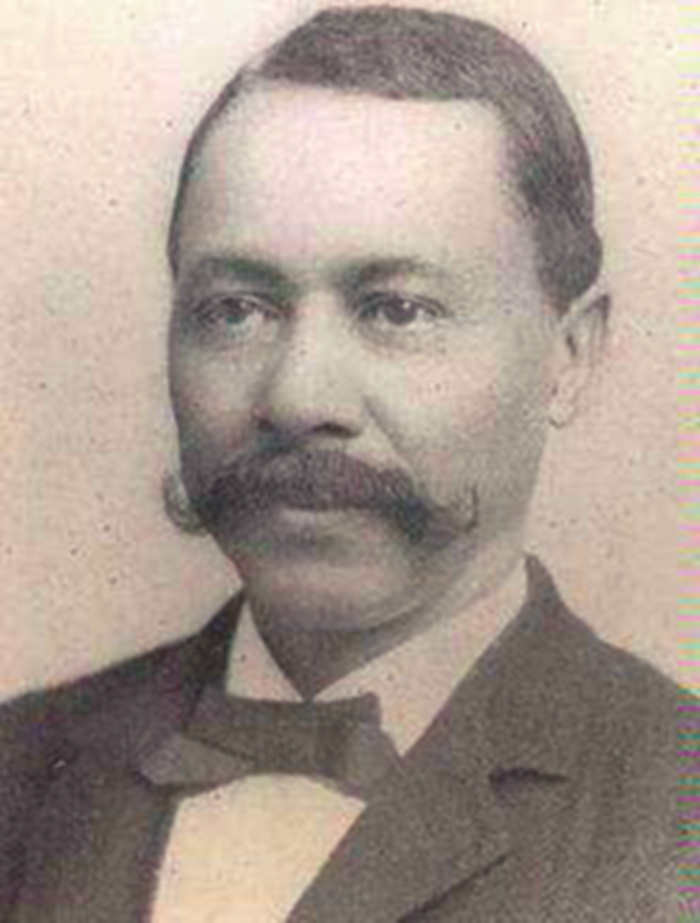

Ebenezer Bassett

Until just a few years ago, Ebenezer Don Carlos Bassett ran the real possibility of becoming entirely forgotten to history. As a young diplomat in 1999, I accidentally “rediscovered” Bassett when I began my first overseas tour in the Dominican Republic.

While walking down the hall to the office of our ambassador for a courtesy call during my first week in country, I scanned the array of pictures on the wall depicting previous U.S. envoys to the island of Hispaniola. While I recognized a few, such as Frederick Douglass, I knew nothing about Bassett, one of the first figures portrayed. Nor did anyone else in the embassy seem to know anything about him.

My curiosity was piqued and I began researching Bassett’s background. What I found was an incredible story, which led me to write his biography: Hero of Hispaniola: America’s First Black Diplomat (Praeger, 2008).

In 2001, the world celebrated when Colin Powell became the first African-American Secretary of State. But Bassett, who helped blaze the trail that would lead to Powell’s appointment, also deserves recognition. Not just because his 1869 appointment by President Ulysses S. Grant as ambassador to Haiti and the Dominican Republic broke the color barrier, but because his courage and integrity would inspire later diplomats and defenders of human rights.

A Proud History of Activism

Born in Connecticut, on Oct. 16, 1833, Bassett came from an activist family. His grandparents were slaves, but his grandfather gained his freedom by volunteering to serve in the Revolutionary War. His father, also named Ebenezer, was mixed race, and his mother, Susan, was a Pequot Indian.

His family worked hard to ensure that Ebenezer would receive the finest education possible. After attending a prep school, Wesleyan Academy in Wilbraham, Massachusetts, the young Bassett did something quite rare in the mid-1800s: not only did he attend college, he became the first black student at the Connecticut Teachers College (now Central Connecticut State University), graduating in 1853.

In 1855, while in New Haven, Bassett married Eliza Park, and developed what became a four-decade friendship with the great abolitionist, Frederick Douglass. He later became a teacher and principal at the Institute for Colored Youth, a Philadelphia high school. It was there that he came into his own as a voice for human rights, advocating equal treatment for black Americans and later helping Douglass recruit black soldiers for the Union Army during the Civil War.

The new president was eager to reward leaders in the black community like Bassett who had helped preserve the Union.

Just days after the Battle of Gettysburg, Bassett and other black leaders organized a recruiting drive for black soldiers. Bassett had the honor of being the second speaker of the night, making his speech immediately preceding Douglass. The following excerpt explains why he, too, was considered such an effective orator:

“Men of color, to arms! Now or never! This is our golden moment. The government of the United States calls for every able-bodied colored man to enter the army for three years of service, and join in fighting the battles of liberty and the Union. A new era is open to us. For generations we have suffered under the horrors of slavery, outrage and wrong; our manhood has been denied, our citizenship blotted out, our souls seared and burned, our spirits cowed and crushed, and the hopes of the future of our race involved in doubts and darkness.

“But how the whole aspect of our relations to the white race is changed! Now, therefore, is the most precious moment. Let us rush to arms! Fail now, and our race is doomed on this soul of our birth.”

That activism proved crucial years later when General Ulysses Grant won the White House in 1868. The new president was eager to reward leaders in the black community like Bassett who had helped preserve the Union.

Correspondence between Bassett and Douglass discloses that Bassett suggested in 1867 that the world-famous Douglass apply for the position in Port-au-Prince when the next president took office. But Douglass instead persuaded Bassett to put his name forward as the American minister to Haiti and the Dominican Republic, which share the island of Hispaniola. (The United States would not begin using the title of “ambassador” until 1893.) This was a time before a professional diplomat corps, and appointments were always based on connections and politics. Nevertheless, Bassett proved himself more than up to the task.

Once Grant won the White House, the new president made history by nominating Bassett as the first African-American diplomat.

A Difficult Debut

When the 36-year-old Bassett arrived at his posting in June 1869, the country was in the midst of civil war. Even as hundreds of civilian refugees filled his residential compound in Port-au-Prince to escape the violence, the State Department sent instructions denying Bassett authority to accept any of them, for fear of being seen to take sides in the conflict.

Bassett was stuck in a quandary: Should he force out the women and children that huddled in his residence, or defy official orders? As rebel forces finally overwhelmed the remnants of the old regime, Bassett not only negotiated safe passage for the refugees but personally escorted them to safety.

Bassett’s courage in literally placing himself in the line of fire to protect the rights of refugees and noncombatants should still inspire us a century-and-a-half later.

Over the next eight years, Bassett would face several similar incidents. In all cases, he stood on the side of humanitarian treatment and the rule of law. On a more mundane level, Bassett oversaw cases of citizen commercial claims, diplomatic immunity for consular and commercial agents, and aid to citizens affected by hurricanes, fires and numerous tropical diseases. By virtue of sheer longevity, he eventually became dean of the diplomatic corps, and enjoyed the respect and friendship of his colleagues.

At the end of the Grant administration in 1877, Bassett submitted his resignation, as was the custom with a change of hands in government. Acting Secretary of State F.W. Seward wrote to Bassett, thanking him for his years of service:

“I cannot allow this opportunity to pass without expressing to you the appreciation of the department for the very satisfactory manner in which you have discharged your duties of the mission at Port-au-Prince during your term of office. This commendation of your services is the more especially merited because at various times your duties have been of such a delicate nature as to have required the exercise of much tact and discretion.”

In something almost impossible to imagine now, when Bassett returned to the United States, he spent a decade as the consul general for Haiti in New York City, serving as an effective bridge between the two countries. Though Bassett longed for another appointment with the State Department, it was not to be.

However, in 1888, when Benjamin Harrison won the White House, he nominated Frederick Douglass to the position in Haiti. Douglass, who was elderly by that point, knew he was unable to do the job on his own and called upon Bassett to accompany him. In an incredibly unselfish act, Bassett returned to Port-au-Prince as Douglass’ assistant when the great abolitionist served as U.S. diplomat from 1889 to 1891.

Sadly, unlike many of his peers who broke the color barrier in other professional fields, his accomplishments would soon be forgotten. Ebenezer Bassett died on Nov. 13, 1908, at the age of 75.

At left, Bryan Anderson, Ebenezer Bassett’s grand-nephew, and Chris Teal discuss the documentary film project.

Courtesy of Chris Teal

Restoring Bassett’s Legacy

Thankfully, over the past several years, more people are beginning to review Bassett’s legacy and examine his pioneering work as an advocate for human rights in foreign policy. After my publication of his biography in 2008, his home state of Connecticut began recognizing the contributions of this distinguished native son. Both Central Connecticut State University and Yale University have established scholarships and awards in Bassett’s name, including the Bassett Award for Human Rights.

With support from the Una Chapman Cox Foundation and Arizona State University's Walter Cronkite School of Journalism, I now seek to expand upon this trailblazing American’s work for broader audiences with my film, “A Diplomat of Consequence.” This is not just an historical documentary, however. Bassett’s legacy demonstrates what diplomats have accomplished and what they do in today’s complicated environment. The film will bring in contemporary voices of minority diplomats as a crucial component of why diversity in foreign affairs still is imperative for successful engagement today.

I began my production shooting in the fall of 2017, filming interviews and footage in both Connecticut and Washington, D.C. During the spring of 2018, I traveled to Haiti and the Dominican Republic for a final round of interviews and filming. My goal is to release the documentary in 2019, in time to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Bassett’s appointment.

Bassett’s courage in literally placing himself in the line of fire to protect the rights of refugees and noncombatants should still inspire us a century-and-a-half later. Similarly, his eloquence and determination in justifying those decisions to his government are precursors of the key role human rights would eventually assume in U.S. foreign policy.

In the end, this is a story of character. Bassett broke many barriers through his life, and he never hesitated to do the right thing. Bassett was an important individual in tumultuous times for the United States, and his work as a diplomat deserves to be widely known and celebrated.