From Finland with Warmth

A Finnish FSO explains some of the unique features of the Finnish Foreign Service, including “sauna diplomacy.”

BY AARETTI SIITONEN

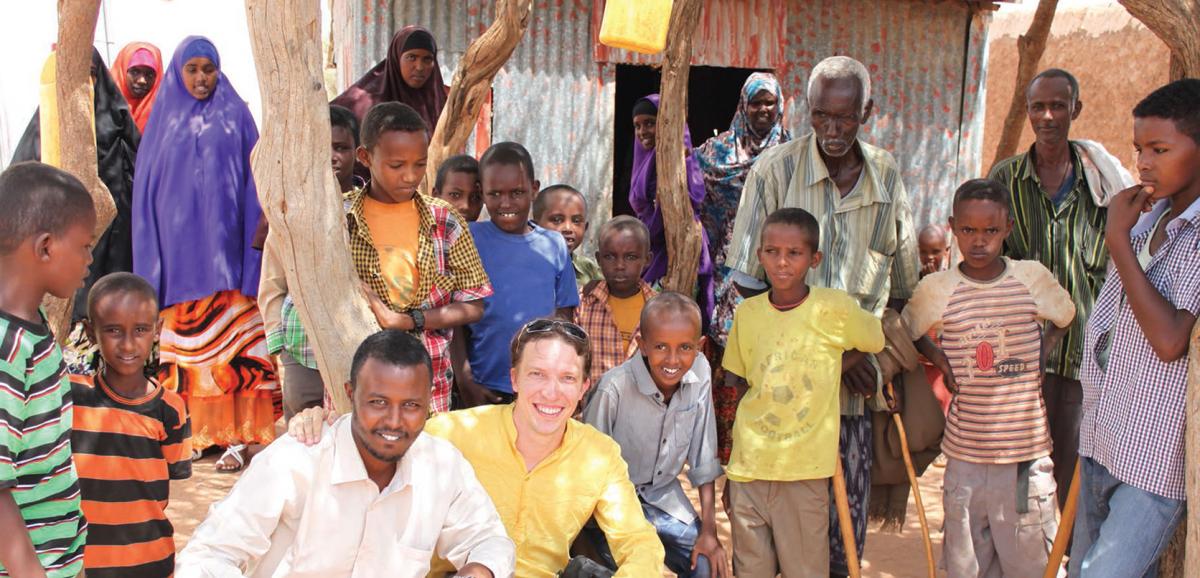

Aaretti Siitonen visiting a Finnish-funded literacy, women’s empowerment and anti-female genital mutilation project near Burao, Somalia. Timo Behr

During my year as a Transatlantic Diplomatic Fellow at the State Department (2012-2013), I was completely immersed in the work of my bureau, advancing United States goals in South and Central Asia. I even had the chance to travel to the region, visiting U.S. missions to exchange views between posts and Main State. It was a roller-coaster year of briefing checklists, annotated agendas and interagency coordination. I wouldn’t trade a minute of it for anything.

When colleagues ask me to describe the differences between the Finnish Foreign Service and its American counterpart, I always respond that it’s far more interesting to notice how much we have in common. We share values and face similar challenges, such as the ever-present problem of differing viewpoints at post and headquarters. We both operate in multiple time zones and wildly different environments; and we both strive to balance diplomatic careers with personal lives. As a result, we can also find common solutions.

Now that six months have passed since I returned to work at the Finnish Embassy, however, the time is right for a more systematic comparison. (By the way, our chancellery on Massachusetts Avenue, the first LEED-certified embassy in the United States, was prominently featured in the April Foreign Service Journal.) Even though the trip from Foggy Bottom to Observatory Circle isn’t long, it does give some perspective.

The Finnish foreign aid agency was merged with the foreign ministry in the 1990s.

Differences in Scale, but Not Purpose

Just like the State Department, the Finnish Foreign Ministry aims to advance national interests. Thankfully, that term is no longer narrowly defined. Strengthening international stability, security, peace, justice and sustainable development across the planet are all part of our portfolio. Similarly, promoting the rule of law, democracy and human rights is as integral to our diplomatic work as representing Finland in foreign capitals and international institutions. Sound familiar?

The most obvious difference between the Finnish Foreign Service and that of the United States is the scale of the operation. Our foreign ministry employs about 2,500 individuals, of whom a thousand are local hires; just 570 or so are Foreign Service officers, about half of whom serve abroad at any given moment. The State Department is roughly 20 times larger, and manages more than 250 overseas posts, whereas the Finnish Foreign Ministry runs 93.

Finland’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs in Helsinki. Courtesy Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Finland

That said, operating a small post requires many of the same ingredients as a larger one, ranging from administrative functions to the actual meat and bones of diplomacy. Benjamin Franklin may have kept a household in Paris, and John Adams originally lodged with a landlady in Amsterdam; yet both dealt with the highest authorities in their respective host countries.

A smaller scale can make it easier to set priorities: Rather than try to do or follow everything, we sharpen our focus. Yet even in a small and nimble service like Finland’s, it is easier said than done. Every function of a bureaucracy tends to find a way to justify its existence, often with very good arguments. Messages cannot go unanswered for long, and once we take on a challenge, we don’t just do an adequate job. We aspire to be exemplary.

From an individual diplomat’s perspective, the difference in scale tends to mean assuming more responsibility, faster. Many of my colleagues who joined the service at the same time as I, four years ago, are already serving as deputy chiefs of mission across the globe.

To put it another way, we are larger parts of a smaller machine. This difference in perspective, combined with the values we share with our American peers, can make for many fruitful conversations between our diplomats in third countries.

Finnish diplomats need to speak the language of the U.S. Agency for International Development, as well as that of State, if we hope to be truly effective in Washington.

Foreign assistance is another case in point. The Finnish foreign aid agency was merged with the foreign ministry in the 1990s; since then, most Finnish diplomats can also expect to take part in development work at some point in their careers.

Considering the fact that the State Department also controls the foreign aid budget, this is not such a big difference. But it does means that Finnish diplomats need to speak the language of the U.S. Agency for International Development, as well as that of State, if we hope to be truly effective in Washington.

No Cones, No Line

Aaretti Siitonen enjoying cherry blossom season in Washington, D.C.

Ahu Yigit

There is no formal “cone” system in the Finnish Foreign Service. Officers do specialize to some extent, but we’re still all expected to be jacks-of-all-trades, as well. To help balance this, the Finnish Foreign Ministry employs experts, much like the State Department’s many highly qualified and professional civil servants and contractors, for particular tasks that require more specialized skills.

The clearance system, the multiple layers of staffers and “the Line” are conspicuously absent from the Finnish Foreign Service. We do have equivalent arrangements, but our structure is much less formalized than State’s.

My colleagues in SCA might make fun of me for saying this, but I actually enjoyed the clearance process at State (most of the time!). It makes collaboration the norm, and brings everyone up to speed on the department’s multifaceted agenda. Taking an axe to the something-for-everyone Christmas tree that the process sometimes produces takes guts; but when used correctly, it is an effective system.

Longer Postings and More Women

Finnish Ambassador Antti Sierla once observed: “The personnel structure of the Foreign Ministry resembles an aged sherry. Every year a new batch with singular characteristics is added, but the preceding vintages continue to tenaciously affect both the hue and aroma of the whole.”

Our foreign postings tend to be three or four years long, and typically a Finnish diplomat will spend the first two years of his or her career at the ministry in Helsinki, gaining experience in different departments. For my part, after having had a new work environment every year for five consecutive years, this posting in Washington, D.C.—hectic and demanding as it may be—feels like a calm haven.

The median age of Finnish diplomats entering the service hovers around 30, so for many it is a second career. The Finnish Foreign Service is also increasingly female. The female to male ratio is set to reach 60/40 by the end of the decade, though the upper echelons are not yet quite as far along on the path to becoming more gender-balanced. The present Finnish ambassador to the United States is the first woman to head our mission here, and it is inspiring to be at the forefront of gender equality in this field of international relations.

To keep in step with the times, the diplomatic corps of all nations also need to become more ethnically diverse. During my year as a TDF, I was impressed by how the State Department is increasingly able to draw on the richness of American society in this regard, as well. Finland is becoming more diverse with every generation, and we will do well to learn from the experience of our American friends.

The clearance system, the multiple layers of staffers and “the Line” are conspicuously absent from the Finnish Foreign Service.

Sauna Diplomacy

Speaking of warm relations, there simply is no substitute for what we Finns call “sauna diplomacy.” Some even argue that it helped keep Finland, which borders modern Russia and shared a long border with the Soviet Union, safe during the Cold War.

The only loanword the English language has taken from Finnish, a sauna is a space to share one’s thoughts in a setting of trust. The aim of sauna diplomacy is not to make anyone uncomfortable, but to hit “pause” for a while, reveal the thinking behind different perspectives, and find common ground.

A sauna is always the first building that Finnish peacekeepers in Kosovo, Afghanistan or elsewhere set up within their perimeters, and it is an integral part of Finnish social life. This past winter, it was especially popular here in D.C.!

It has been great to share this and other facets of Finnish culture with American friends and colleagues during my time at State and later, just as my wife and I have been welcomed into the homes and lives of the people here. We’ve become addicted to turkey with stuffing at Thanksgiving, and find it hard to imagine a Nats game without half-smokes from Ben’s Chili Bowl. The dynamism, honesty, openness and warmth we’ve found in Washington have simply blown us away.

The natural ease of our countries’ cooperation, both during the fellowship and in my current position back at the embassy, has been truly remarkable. I felt like a part of the team ever since I first stepped into the Harry S Truman Building, and my colleagues at the embassy and I look forward to helping our countries work together on the issues that shape our common future.